Revision: Re-Seeing Your Writing

Writing as a Process of (Radical) Revision

Strong, effective writing requires the process of freewriting, questioning, and continuous revision.

Many writers tend to understand revision as simply making surface changes to existing text—substituting words or phrases (proofreading and editing) rather than reconsidering essay drafts holistically.

Radical revision is an approach to drafting that presumes the first draft, even the most well-crafted one, needs deep reconsideration and restructuring in order to clarify argument in conversation with an audience. In other words, revision is a process by which a writer can:

- Generate missing thinking on the page.

- Rewrite (from scratch) parts that are not yet doing the work the writer needs them to do.

- Sacrifice anything in the draft that does not sustain its conceptual or formal coherence.

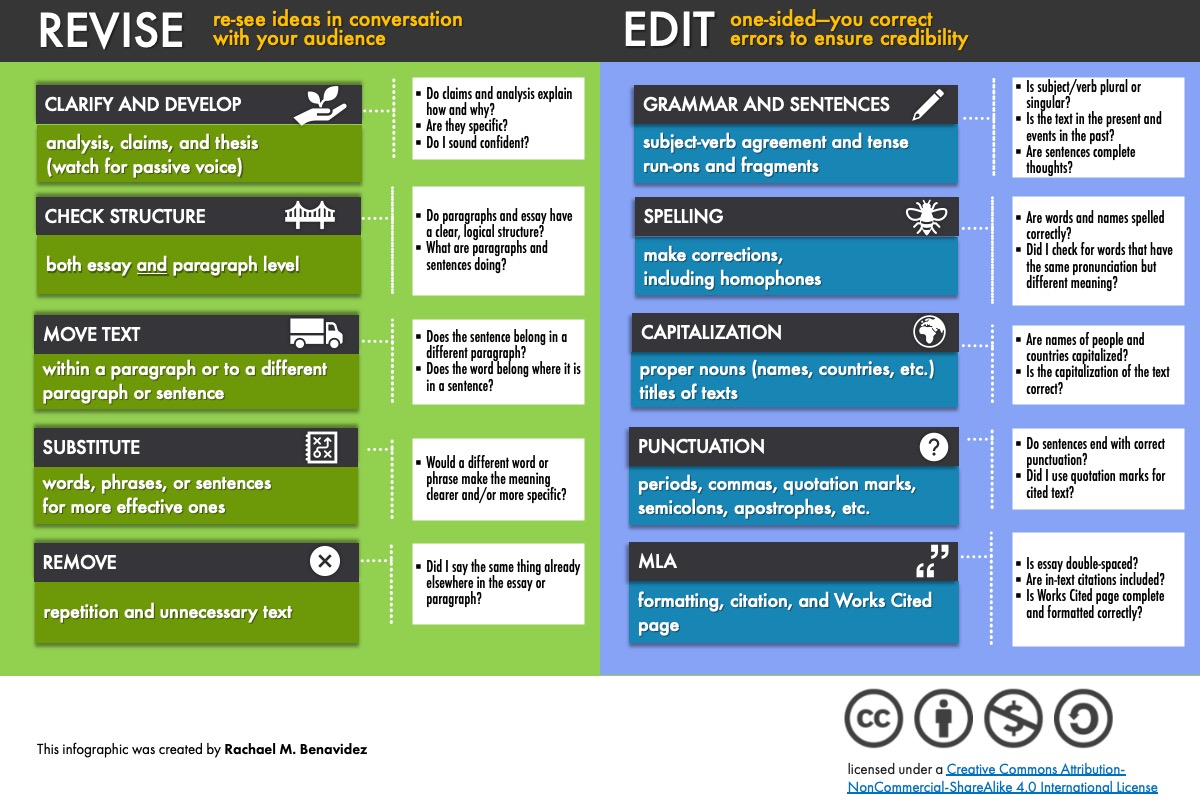

Revision vs. Editing

- Revise on a rolling basis. In each of your essay drafts, you are expected to extensively revise your writing to develop and ensure the clarity and specificity of your argument.

- Edit as a final step. Before you submit a final draft of an academic essay, you are expected to edit it to ensure correctness in spelling, grammar, and citation, etc.

Use this infographic as a guide for revision and editing.

Radical Revision

by N. B. Wallack, Columbia University, and C. Moore, New York University

Many writers tend to understand revision as simply a matter of making surface changes to existing text—substituting words or phrases rather than reconsidering their drafts holistically. Radical revision is an approach to drafting that presumes the first draft even the most well-crafted one a writer can make to be in need of deep reconsideration and restructuring. That is to say, revision is a process by which a writer can generate missing thinking on the page, rewrite (from scratch) parts that are not yet doing the work the writer needs them to do, and sacrifice anything in the draft that does not sustain its conceptual or formal coherence. While some writers love revision and find it to be the most satisfying part of the composing process, many others find it very challenging and even upsetting; after all, it is hard to let go of writing, and it is hard to re-approach our own work coolly and ruthlessly.

Note what your readers have given you as feedback on your draft, and consider what concerns you may have about it yourself, then try a few of these approaches for prose or essays:

- Go to a place in your draft where you need to say more. Write to explain. Exhaust yourself.

- Go to a place in the draft where you seem to be getting at your idea. Write to explain what that idea might be.

- Write an impossible, or surprising, but connected story that comes to mind as you read your draft. You don’t know how it fits, but write about it anyway.

- Find a place in a published text that helps you think about your idea. Copy the passage out and explain how it connects. Find a place for it in your draft.

- Use a passage from another text to resist or doubt something you are writing about. Write to explain the counterargument.

- Write a summary of one of the texts you are working with. Find a place for it in your draft.

- Write a paragraph in which you incorporate two texts. Put these texts in conversation with one another. (How do they extend, confirm, complicate, contradict, correct, or debate one another?)

- Find a key image or key language in your draft. Write to explain what this image or language might mean.

- Rewrite completely the beginning of your draft to articulate specifically the problem your essay is exploring, or to change its focus, tone, or contract.

- Rewrite completely the ending of your draft to account for how your thinking has changed from the beginning and middle of your essay.

- Find an arbitrary (six to eight) number of claims, concepts, or questions in your draft that are most important to what you have written now. Write a six- to eight-line poem that demonstrates how these claims are related to one another.

- Highlight the most important ideas in the middle and ending of your essay. Write a brand-new beginning that articulates this problem.

- Print out your draft and cut it up into sections (a section can be as small as a sentence) that contain some discrete piece of thinking. Ask a friend to reassemble the parts in a new order that makes sense, and to tape it to blank sheets of paper, leaving blank space between ideas that are not explicitly connected. If you like this new order, consider what you might need to write in the blank spaces to make transitions or to flesh out ideas. Throw away pieces that repeat one another in essence, or in fact.