2 Active Reading and Annotation

In college, you’ll be asked to read texts that are rich in ideas and information. They are useful to you for the knowledge and ideas they contain, but also in helping you learn how informed writers organize their ideas and structure arguments. The following provides strategies for beginning actively approach to complex texts.

In order to actively read a text, you first identify important information and then annotate using a combination of color coding, highlighting, underlining, etc.—whichever system works best for you—to summarize and respond to the text. As you read, stay open to possibilities that may contradict your currently held views. With these practices in mind, once you’ve finished reading a text, you should already have the foundations for your response to the author. In other words when you actively read and annotate, you’ve already begun to write!

Review Medium Article

Review the Medium article “College Reading Secrets Your Professor Expects You to Know” by Eric Drown that we discussed in class so that you understand the expectations for this course. Then continue with active reading and strategies.

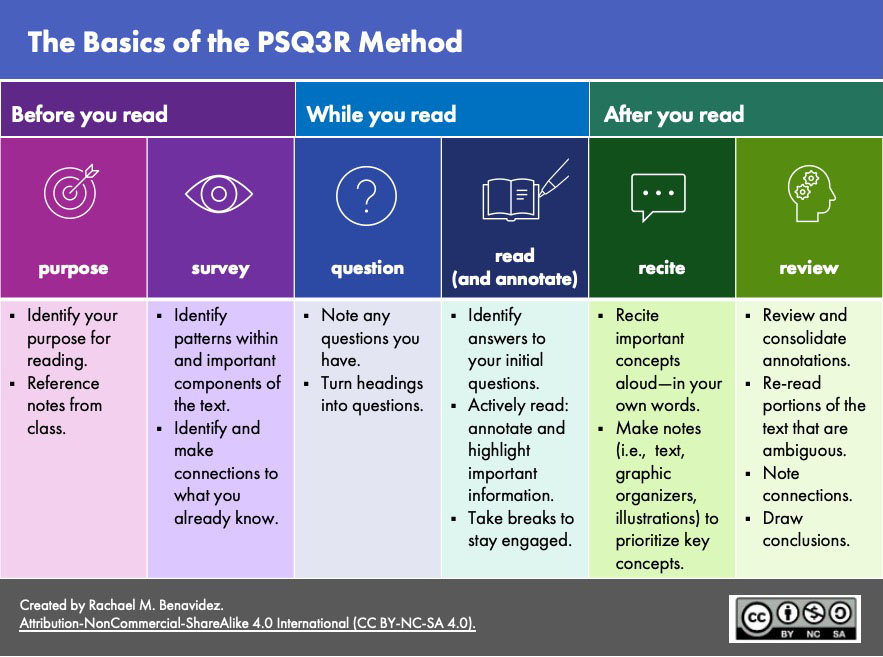

SQ3R—Plus One

SQ3R—Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review—is a textbook reading strategy developed by educational psychologist Francis Pleasant Robinson in 1946 in is book Effective Study. As with any academic practice, others have contributed to the conversation. In this case, Purpose has been added to the beginning of the process, we’ll call the method PSQ3R.

When to use it

Apply strategies from the SQ3R method when reading textbooks for classes like biology, psychology, cultural and media studies, and sociology. It’s especially helpful if your professor expects you to apply concepts or reviews material during class and is most useful with the following genres.

- A chapter or subchapter of a textbook

- A peer-reviewed journal article (scholarly article)

- A newspaper article

- A writing/research assignment

- A study guide

How it’s helpful

- The PSQ3R method requires you to read with purpose and actively engage with the text, which develops your ability to approach challenging texts.

- It helps you to activate your background knowledge of the topic and review the text using different methods.

- It’s especially useful when you’re confused or overwhelmed by a text since it provides strategies for breaking up the text into manageable parts and steps.

Practice and adapt

The process of using the PSQ3R is not automatic and requires practice and patience. Use the model the first few times that you use the PSQ3R method. Once you understand the basic process, you can adapt and customize to what works best for you. The first few times you apply PSQ3R, it will take more time, so plan to start early.

The Basics

First we’ll look a the basics and then take a deeper dive into each of the strategies. Click the image to enlarge and view in a new tab.

Before You Read

Purpose—Identify Why You’re Reading

Your purpose for reading will be different, depending on the discipline and the type of text you’re reading. Your professor will often help you to define your purpose during class, but you will also need to think through why you’re reading. Are you:

- memorizing for a test?

- identifying evidence for analysis (primary source)?

- using the text as a lens (contextual or theoretical source?)

- engaging in conversation with the author? (argument source)

Ask yourself questions like these to help you to determine your purpose.

Survey and Research—Identify Important Information

Before you begin reading, do an active survey of the text, which encourages you to think about your purpose for reaching. As you survey the text, pose questions of its elements.

|

|

Author: Many readers skip this step—but how can you understand this person’s writing, really, if you have no idea of their areas of expertise, body of work and research, what they typically write about, and who they typically write for? Take a few minutes to Google your writer and it will go a long way toward helping you understand their style and ideas, along with their ethos to write about the topic. |

|

|

Genre and Publication: What kind of text is this? In what type of publication(s) has it been published? Is it a peer-reviewed philosophy essay published in a respected philosophy journal? Or an essay on philosophy published in a mainstream magazine? Knowing the genre of the text will help you better understand what conventions (e.g. vocabulary complexity, source usage, citation style) to expect and why they are included. It will also give you insight into the intended audience. |

|

|

Title and Subheadings: What does the title tell you about what the writer is trying to do in this text and what it’s about? Look up words, terms, or references that you are unfamiliar with or cannot precisely explain. Titles are selected carefully so they can tell you a lot, including insight into the author’s argument—yet a lot of readers skip this. In order to engage with the author’s argument, glance over the headings to see how the author structures their argument and content. Turn those headings into questions. |

|

|

Introduction: The introduction is carefully crafted to set up and present the writer’s project i.e. their central question, main idea, and motive or purpose. Read carefully to identify these elements so that you know what the writer is trying to do, and can follow along. |

|

|

Key Terms: Writers often rely on “key terms”—terms that they coin, define, or use to explain important concepts in their arguments. They are often repeated; however, they may be used only once at an important moment in an argument. Watch for these—they are keys to understanding and describing an author’s argument. |

|

|

Topic Sentences: Every paragraph of analysis has a topic sentence or main claim, and the rest of the paragraph is developing or supporting that claim. If you feel like you’re drowning in words and information, look for the main claims—they are your anchors. Even paragraphs that describe or summarize sources have topic sentences; however, these are not usually claims. |

|

|

Conclusion: The conclusion often traces the author’s intellectual movement and argument over the course of the text, and is where the writer leaves their last word, which can involve offering a revised or evolved version of their thesis. Watch for important clues about the point and significance of the project here, and compare to the introduction. How does the writer respond to the explicit or implicit questions that they set up at the beginning? How do they synthesize their argument? Where do they leave us?

|

While You Read

Question

With questioning, you read in order to actively engage with the text.

- Turn headings into questions, which helps you to look for answers as you read.

- What do you need to know?

- What is the author trying to convey?

- What prior knowledge do you bring?

- How does the structure develop the author’s argument?

Active Reading and Annotation—Summarize and Respond

After you have completed your survey and initial questions, you’ll actively read and annotate the text. Keep in mind that by definition, annotation means to add notes, which is the beginnings of an essay. Highlighting is only the first step. While you’ll read some texts in order to memorize or summarize, in most classes, your purpose in reading and annotating texts in college is to respond with your own unique interpretation and ideas.

- Summarize in order to understand what “they say.”

- Respond to the text in order to engage in conversation with the author(s).

| Understand What “They Say” | Respond to What “They Say” |

Use these strategies to help you to understand what the author(s) is saying.

|

Use these strategies to help you to engage in conversation with the author(s).

|

Some content adapted from “They Say / I Say” The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein and Gordon Harvey’s “Elements of the Academic Essay.”

After You Read

Recite

Recite what you’ve read aloud—in your own words.

- By explaining it verbally to yourself (or a friend) you’re able to prioritize key concepts and ideas and to determine any gaps in your understanding.

- Recite at the end of each section of the text and then again when you come to the end.

- Then, write what you’ve just recited.

Review

After you have finished reading and annotating, review and consolidate your annotations—at the end of each section of the text and then again when you come to the end.

- Note any instances in which the text is challenging and review (re-read) portions of the text. Make plausible guesses and then discuss those guesses during your next class meeting.

- Think through and note any connections with the text and your class notes.

- Draw conclusions.

- How would you discuss the text with the author if you were to encounter him or her in a coffee shop? How does this author’s response to an intellectual problem generate entirely new intellectual problems?

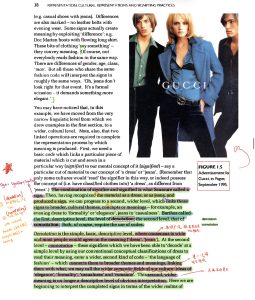

Sample Annotations

Here are some sample student annotations, which she gave permission to show you. Note that you can annotate in any language or any form of English. Your annotations are just for you. Click on the images to enlarge and view in a new tab.

Also see the Rhetorical Situation and Appeals.