22 Understanding Analysis

Virtually every essay assignment you will be asked to complete in college will require you to analyze something. Even if other verbs besides analysis are used in the writing prompt (e.g. discuss, argue, consider, examine, explore, review), the core task in all these essay assignments remains the same: analysis.

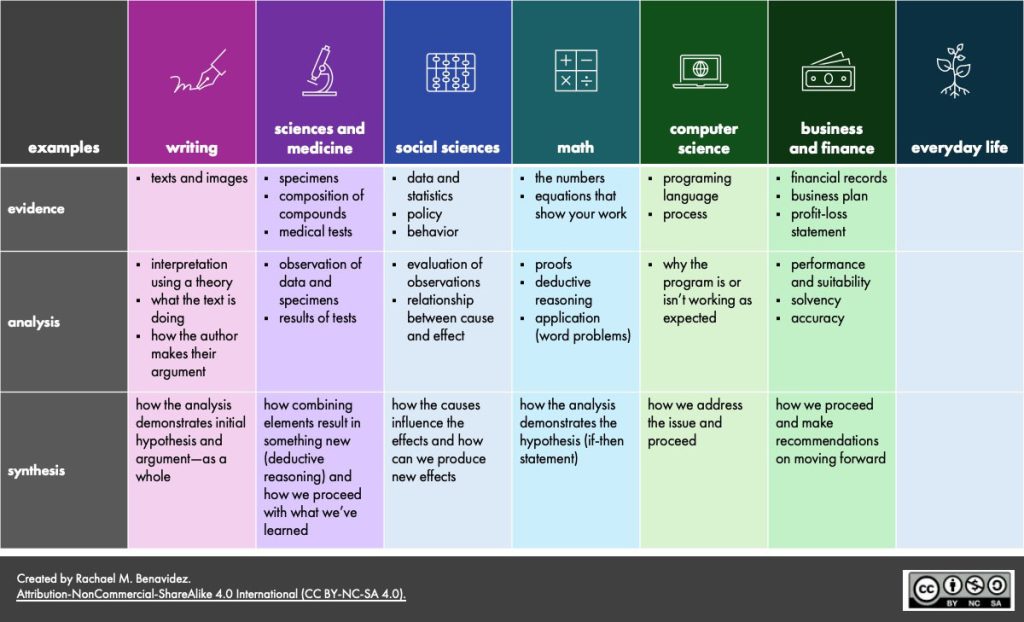

Here are some examples of how evidence and analysis work together in a few academic disciplines. Note that once we have analyzed evidence, we then synthesize or draw conclusions in order to create a thesis. (We are going to work together to think of examples from everyday life.) Click the image to enlarge.

Okay. Great. So, now what does all of that mean in terms of what analysis actually is? And how do you do it in essays? Gaining clarity about analysis is a crucial first step when developing your skills as an academic writer.

Defining Analysis in College Essays

Too often, first-year college students think of analysis as “proof” (not to be confused with mathematical proofs). This way of thinking is likely how you learned to approach making arguments in writing in high school: you provided evidence to “prove” the point you were trying to make in the essay. However, if you continue to think of analysis in this way, you will quickly find that your essays will fall short of the standards expected in college.

Why, though? Because even though it was often sufficient in high school to simply present evidence, in college you are expected to analyze relevant information and ideas in order to develop your own perspective. Therefore, analysis is what you do with evidence; it is how you attempt to examine and explain evidence. In our writing class, we will define analysis using the following simple equation.

In other words, when we analyze something, we identify and examine its parts in order to better understand its composition, meaning, purpose, function, effects, relevance, or significance. But analysis has layers of complexity, so there’s still more to it.

Doing Analysis

First, let us acknowledge that we analyze information all the time in order to navigate our physical world and the innumerable discussions within human civilization. Analysis is what we do with information and ideas around us in order to learn, understand, and navigate the world around us. For example, when we were children playing with dolls or action figures, there was likely some point at which we became curious about the doll in our hands and took it apart—dissected it—in order to better understand what it was or how it worked—interpreted it. Notice that it was our curiosity that led or prompted us to analyze the doll. This is true of all the analysis we do: it is motivated and guided by questions. Put differently, questions lead us to analyze.

For example, the question that led us to analyze our dolls might have been: How does this work? After dissecting the doll and examining how its parts were composed and connected, we would have eventually settled on some sort of answer to that question e.g. The doll’s leg can move around because of the ball at the end that fits perfectly into the ball-shaped hole at the bottom of the doll’s torso. Obviously, our 3-year-old selves won’t have used such vocabulary, but the point remains: analysis is what helps us find acceptable answers to our questions. So let us include that in our flowchart of the analytical process.

Therefore, when we analyze, we dissect and interpret relevant information and ideas in order to discover and develop answers to questions we have.

The Essay Writing Paradox: Doing Analysis vs. Representing Analysis

Early Drafts—Doing Analysis

In order to produce a final draft of an academic essay, a writer typically researches and reads credible sources, and drafts multiple versions of their thinking. Why? Because all this work helps a writer attempt, develop, and revise their analysis in order to discover possible answers to the questions they are trying to answer. In other words, in early drafts of an essay, a writer is actively doing analysis to explore their subject or topic deeply. As a result, their thinking about their topic often changes, so it is common for ideas in their later drafts to look very different to ideas they initially had—and for them to include that thought process and show their changes in thinking in their draft.

Final Drafts—Representing Analysis

The final draft of the writer’s essay will present the strongest answers they found and represent the analysis they did to find those answers. In other words, in the final draft, a writer is showing how the meticulous analysis attempted in previous drafts led them to a strong answer or thesis. Though it often seems that a writer is actively thinking through a problem or question in a well-written essay, the reality is that the essay skillfully represents the writer’s thinking that happened over the process of many previous drafts of that essay. A strong essay shows a writer’s mind at work, which is to say that a strong essay represents how a writer analyzes relevant information and ideas to answer questions.

Let’s try to represent this paradox in our flow chart. In early drafts of our college essays, the analytical process may look like the equation that we initially wrote.

Doing Analysis

However, the final draft of a conventional academic essay is structured differently.

Representing Analysis

The thesis or a hypothesis that a writer typically presents in the introduction of an essay is a statement that introduces what is known through all the analysis done in previous drafts of the essay. It presents an intellectual problem—or question.

The more informed version of that thesis that a writer typically presents in the conclusion of an essay synthesizes all the analysis done in the final draft of the essay, which allows them to draw those conclusions. It leads to new questions.

Adapted from materials by Christoper John Williams.

Also see Argumentation, Identifying Intellectual or Interpretive Problems, and Developing Strong Thesis Statements.