Chapter 1. Psychophysics and Neuroscience.

1.6. Neuroscience research methods

In Module 1.2 you read about psychophysical research methods that allow researchers to investigate the relationship between a physical stimulus and a person’s perception of it. Researchers who study sensation and perception also use neuroscientific techniques to investigate the relationship between a stimulus and the activity it produces within the nervous system (sensation). In many cases, neuroscience studies can also investigate the link between the neural activity that is evoked by a stimulus (physiology) and a person’s perception of it. In this way, we can build stronger ways to understand the relationship between sensation and perception. For example, in a vision test, experimenters can show the participant a flashing pattern of small black and white squares (like a chess board) and then decrease the size of the squares until the participant says they can no longer see them. If brain activity is recorded at the same time, we would see that the visual parts of the brain no longer respond to the squares when the size is reduced to the point that the participant can no longer see them. This then allows the researchers to use the technique to assess visual abilities in nonverbal participants.

Invasive Single Cell Recordings

Invasive techniques, such as lesioning brain regions or implanting recording electrodes in the brain, are commonly used in research with non-human animals to study the processes involved in sensation and perception. In some studies, researchers will lesion or remove a part of the brain, this is called ablation. After the target region is carefully removed or inactivated, the behavior of the animal is tested to determine the function of the lesioned structure. For example, researchers may remove specific components of the association visual cortex and test how the ability to see changes.

In other cases, researchers learn about brain function by implanting recording devices directly in animal brains to ‘listen in’ on brain activity. The animal undergoes a stereotaxic surgery whereby a recording electrode is inserted into a target area of the brain (see Figure 1.11). Different types of invasive electrophysiological recording include: intracellular unit recording, wherein a microelectrode is inserted into a single neuron to measure its electrical activity; extracellular recordings that pick up the firing of one nearby neuron (single unit recording) or several adjacent neurons (multiunit recording); and invasive electroencephalography (EEG), where a large electrode picks up the electrical brain activity of a large number of nearby neurons. These electrodes can pick up neural activity while the animal is performing some task and provide insight into links between neural activity and behavior.

Non-invasive physiological Methods

Just as X-ray technology allows us to peer inside the body, many different types of neuroimaging techniques allow us to view the working human brain (Raichle,1994). Each method allows us to “see’” brain activity through a different lens, and each has its advantages and disadvantages (Biswas-Diener, 2023).

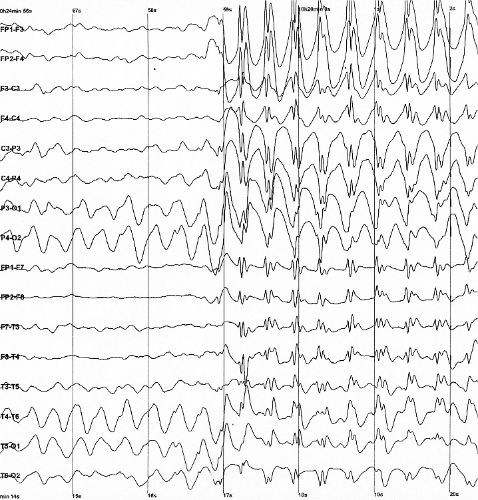

Electroencephalography (EEG) has been used for more a century (e.g., Berger, 1929) to measure the electrical activity of the brain. When large populations of neurons are active, they create a small electrical voltage that passes through the skull and scalp. Electrodes placed on the participant’s head pick up the voltages, which are amplified and recorded (see Figure 1.13). Researchers can record the voltages from brain activity as the participant performs a task (Figure 1.14).

Because the small voltages are distorted as they pass through brain tissue, skin, and bone, researchers only have a rough idea where in the brain a signal was generated. This uncertainty is especially the case for signals coming from deep within the brain. Thus, EEG’s spatial resolution of where something occurs in the brain is rather low. We call this property spatial resolution. Conversely, EEG’s temporal resolution is excellent and indicates when something happens in the brain to the millisecond. With the excellent temporal resolution, EEG is well suited for examining the brain’s response to a stimulus event. These types of signals are called event-related potentials (ERP). In a typical ERP experiment, researchers might play a visual or auditory event like a word, then measure the corresponding voltage changes that unfold in the brain over the next few hundred milliseconds. The amplitude, timing, and topography (position) of the EEG signal capture the underlying neural/mental processes.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is similar to EEG, but instead of electrical signals, MEG picks up the weak magnetic fields generated by the flow of electrical charge associated with neural activity. Because the magnetic fields generated by brain activity are so small, special rooms are needed that shield out magnetic fields in the environment so that the MEG sensors can pick up magnetic fields from neural activity without environmental contamination. Similar to EEG, MEG also has excellent (millisecond) temporal resolution. The spatial resolution of MEG is far better than that of EEG because magnetic fields are able to pass relatively unchanged through hard and soft tissue and therefore are not distorted by skull and scalp. In spite of MEG’s excellent spatial and temporal resolution, it is used much less widely than EEG because the MEG apparatus is much more expensive and unwieldy than that for EEG.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

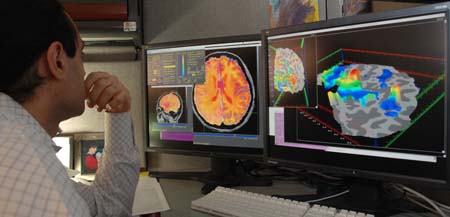

Many imaging technologies can capture detailed inner images of the brain and the activity within it that is caused by a stimulus. In the 1970s, the development of computerized tomography (CT) scans allowed non-invasive imaging of the living brain using X-rays. CT scans are rarely used today for purely research purposes due to the radiation exposure and relatively low image resolution. Similarly, although PET scans can provide images of the brain by detecting the presences of radioactive markers that are inhaled or injected, they are not commonly used anymore because they expose participants to low-levels of radiation. The most commonly used brain-imaging modality today is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Different types of scans from the same MRI machine can give high resolution images of brain structure (structural MRI) and brain function (functional MRI or fMRI). MRI scanners may be expensive, noisy, and claustrophobic to some, but they are harmless and painless and are powerful and prevalent tools for illuminating brain structure and function.

MR scanners use a strong magnetic field that is around 60,000 times stronger than the earth’s magnetic field. As a person lies very still in the scanner, the magnetic field forces protons in their body to align. Pulsations of low-energy radio frequencies cause the protons to change their spin. As the radiofrequency is turned off, these protons return to their aligned state and give off energy that is detected by MRI sensors. The timing and amount of energy released as the protons realign with the magnetic field differs based on the type of tissue, and can clearly depict differences between the brain’s white matter, gray matter, cerebrospinal fluid, bone, blood, blood vessels, etc.

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) creates detailed images of brain structure with millimeter resolution. The high-resolution 3D images might show the brain’s gray matter and white matter in voxels (i.e. like 3D pixels) that are 1mm x 1mm x 1mm cubes. Researchers may use the image to compare the size of structures in different groups of people (for example, Are areas for controlling the fingers in the motor cortex larger in string musicians than vocalists or trombonists?). These structural images can also be used in conjunction with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures activity.

Functional MRI (fMRI) uses the same MR scanners, but instead of capturing a high-resolution snapshot of brain structure, it measures brain “function” or activation while a subject performs some task. As a brain region becomes more active, it uses oxygen and causes an inflow of oxygenated blood to that region over the following few seconds. fMRI measures the change in the concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin, which is known as the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal. From the BOLD signal, researchers infer neuronal activation in that brain region (note that fMRI does not directly measure the neuronal activity). Because cerebral blood flow is coupled with neural activation, researchers can map brain activation while people in the scanner perform tasks like reading, speaking, viewing images of faces or places, recalling memories, etc. In this way, fMRI provides evidence of localization of function and which areas are active during specific tasks. fMRI has high spatial resolution and the activation maps in a typical fMRI study consist of cubic voxels that are a few mm on each side. However, the temporal resolution of fMRI is quite poor and it typically takes a snapshot of brain activation averaged over a 2 or 3 second window.

In addition to measuring BOLD responses while subjects perform some task, fMRI can measure subjects’ brain activation over many minutes while they perform no task (so-called “resting state scans” wherein they might lay in the brain scanner for 10 minutes while instructed “don’t do anything in particular”). These can often be used as control conditions,

While fMRI is popular and powerful and people find the pretty images convincing, they are correlational and don’t fully explain the causal role of specific brain regions in determining mental processes. This is an important example of why it is essential to rely upon converging evidence—as an example, correlational fMRI data coupled with causal experimental data from lab animals. Also to address some of the limits of correlational research, researchers are developing techniques that can directly modulate brain activity.

In order to establish a causal rather than correlational relationship, we need to alter brain function and observe subsequent change in behavior. Lesions are one way to alter the brain and can reveal a casual relationship (e.g., when losing a brain region leads to loss of function, that brain area is necessary or involved in the function). However, invasive lesions can only be introduced in animals, which differ from humans in key ways. Lesions in human brains can only be studied in patient populations; that is, after a patient experiences brain damage from a stroke or other injury. New technologies have been developed that allow researchers to temporarily and non-invasively alter brain function in humans.

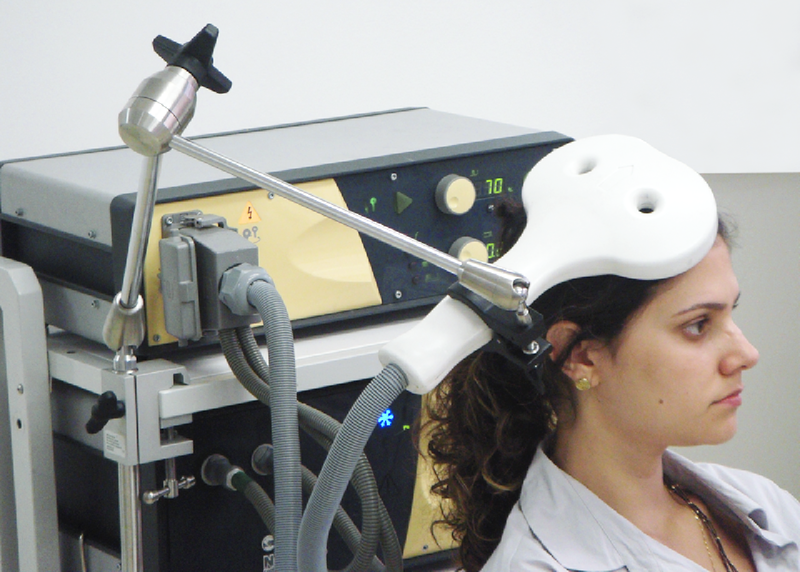

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a form of brain stimulation that uses magnets to alter brain activity. Researchers place a magnetic coil over the scalp and apply a magnetic current that stimulates the neurons below the magnetic coil (Figure 1.17). Depending on the type and rate of magnetic pulses, TMS can be used to temporarily “turn off” or “turn on” the brain area under the coil. In research domains, researchers might temporarily “turn off” or “turn on” parts of the temporal lobe and look at how it affects people’s ability to understand speech sounds.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is similar to TMS except that it uses electrical current directly (rather than inducing it with magnetic pulses) via small electrodes on the skull (Beck & Tapia, 2023). A brain area is stimulated by a low current (equivalent to an AA battery) for an extended period of time.

In sum, the various research techniques used in sensation and perception research each have their own strengths and weaknesses in terms of spatial resolution, temporal resolution, ease-of-use, invasiveness, cost, precision, etc. Using the different tools in a complementary manner provides converging evidence for understanding how the brain works.

Parts of this chapter were adapted from:

Beck, D. & Tapia, E. (2023). The brain. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/jx7268sd

Biswas-Diener, R. (2023). The brain and nervous system. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/4hzf8xv6

References

Berger, H. (1929). Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 87(1), 527-570.

Brasil-Neto, J. P. (2012). Learning, memory, and transcranial direct current stimulation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 3(80). doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00080.

Infantolino, Z. & Miller, G. A. (2023). Psychophysiological methods in neuroscience. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a6wys72f

Raichle, M. E. (1994). Images of the mind: Studies with modern imaging techniques. Annual Review of Psychology, 45(1), 333-356.

In recent years, computer algorithms have started catching up to human observers’ skill at recognizing objects, which is to say, correctly categorizing parts of an image according to uses or identities. But object definitions are not clear cut; they tend to be rather operational (defined by the utility of the situation). This chapter originally created by: Jaclyn Bowen, Tessa Rossini, Hannaan Shire, John Taylor, Hannah Thormodsgaard, Ashlynne VanHorn, Jamie Wahout, Ariyanna Watts, and Elton Wong and edited by Jill Grose-Fifer.

Learning Objectives

- Describe some of our visual experiences that illustrate the problem of ambiguity.

- Describe the Gestalt Principles that influence our perception of objects

Learning Objectives

Be able to diagnose whether a given experiment measures an absolute threshold, a difference threshold, or is a magnitude estimation experiment

Be able to describe a couple of different methods of estimating a threshold

Know what a subliminal message is

Know Weber’s law (also called Weber-Fechner law)

Scientists who study sensation and perception often use psychophysical techniques in their research studies. Psychophysical methods investigate a person's (psychological) response to a physical stimulus. In other words, how does a physical change in a stimulus affect a person's perception of it? Psychophysics helps to build a bridge between the physical world and our experience of it. For example, psychophysical methods can help us to determine how loud a sound needs to be before we can hear it or how much sugar we need to add to a cup of coffee to make it noticeably sweeter. Psychophysical methods typically measure people's sensitivity to sensory stimuli in terms of thresholds. For example, you might describe yourself as someone who is highly sensitive to pain - in other words you have a low threshold for pain. Researchers can measure your threshold for pain with considerable accuracy using psychophysics.

We can measure different types of sensory thresholds, but let's begin with a common concept in sensation and perception - an absolute threshold. An absolute threshold is the minimum amount of stimulus energy that must be present for a person to detect a stimulus. Another way to think about this is that we can ask how dim can a light be or how soft can a sound be for us to be aware of it The sensitivity of our sensory receptors can be quite amazing. It has been estimated that on a clear night, the most sensitive sensory cells in the back of the eye can detect a candle flame 30 miles away (Krisciunas & Carona, 2015) . https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06270

Absolute thresholds are generally measured under incredibly controlled conditions in situations that are optimal for sensitivity. There are three common techniques for measuring thresholds.

Psychophysical Methods

- Method of Limits. The experimenter presents stimuli of gradually changing intensity (either increasing or decreasing) until the observer reports a change in perception. If multiple measurements are taken this method can be time-consuming but provides quite accurate measurements.

- Method of Adjustment. This is very much like the Method of Limits, except the experimenter gives the observer a sliding control to adjust the stimulus intensity until they can just perceive it. This is a much quicker method than the Method of Limits and so may be helpful for participants with limited attention, but it is less accurate.

- Method of Constant Stimuli. This is the most reliable, but most time-consuming method. The experimenter presents many stimuli of different intensities in a randomized order and graphs the observer's responses. The graph is used to calculate the stimulus intensity at which the observer perceives the stimulus 50% of the time.

Let's take a closer look at these three different methods, with some specific examples to help you to understand what it would be like to be a participant in one of these studies.

Let's start with the Method of Limits. Let's imagine the experimenter wants to measure the absolute threshold for a small circle of light. As we can see in Figure 3, the experimenter first presents a light with very low brightness (1 unit) and asks the participant whether they can see it - if they cannot they record a no response in the table and then very gradually increase the brightness one step at a time until the observer says they can see the light (in the example below this occurs when the light is 29 units of brightness). The experimenter then stops increasing the brightness and records the response as a Yes. This set of steps is called an ascending staircase because the brightness was increasing. The threshold on this staircase is estimated to be halfway between the last "no" response (22 units) and the first "yes" response (29 units) i.e., 25.5 units of brightness. This is also called the cross-over point. The ascending trial is followed by a descending trial. In the descending staircase, the light starts off bright (50 units) and is gradually decreased in intensity until the observer says they can no longer see it (15 units). The cross-over point on this staircase is between the last "yes" response - 22 units and the "no" response (15 units).

It is quite common to have higher thresholds on ascending compared to descending staircases. This is thought to be due to errors of habituation. In other words, we get into a "routine" or a habit of giving the same response. In ascending staircases, the habitual response is to say no, this means we tend to go past the actual threshold before we change to a yes response. The opposite is true for descending trials. One way to try and compensate for these errors is to use multiple and equal numbers of ascending and descending staircases and then calculate the average of the thresholds across all the staircases. In the example below we have two ascending staircases and two descending ones - so we can take the mean of four cross-over points. Experimenters also use different starting points on each staircase type to avoid the participant trying to guess when they should change their response - based on the previous staircases. This helps us to avoid these errors of anticipation. In this example, the first ascending staircase starts on 1 unit of brightness, but the second one (2A) on 8 units.

| Brightness | Ascending staircase (1 A) | Descending staircase (1D) | Ascending staircase (2 A) | Descending staircase (2 D) |

| 50 | Yes | |||

| 43 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 36 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 29 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 22 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | No | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | No | No | No | |

| 1 | No | |||

| Cross-over point | 25.5 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 11.5 |

Sometimes, we are more interested in how much difference in stimuli is required to detect a difference between them. This is known as the just noticeable difference (JND) or difference threshold. Unlike the absolute threshold, the difference threshold changes depending on the stimulus intensity. As an example, imagine yourself in a very dark movie theater. If an audience member were to receive a text message on her cell phone which caused her screen to light up, chances are that many people would notice the change in illumination in the theater. However, if the same thing happened in a brightly lit arena during a basketball game, very few people would notice. The cell phone brightness does not change, but its ability to be detected as a change in illumination varies dramatically between the two contexts. Ernst Weber proposed this theory of change in difference threshold in the 1830s, and it has become known as Weber’s law: the difference threshold is a constant fraction of the original stimulus, as the example illustrates.

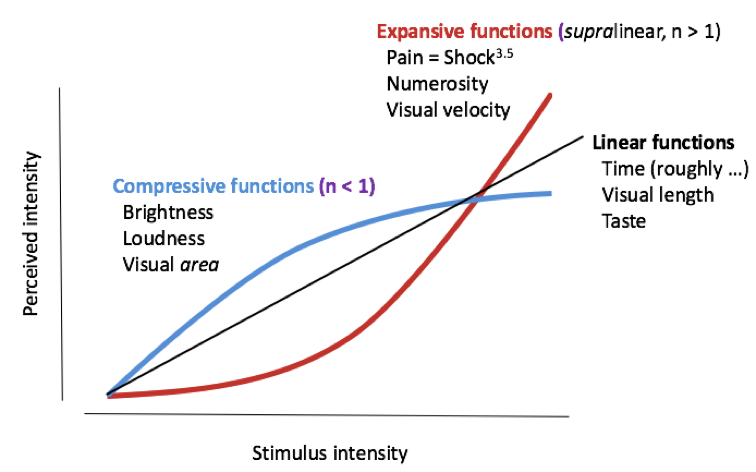

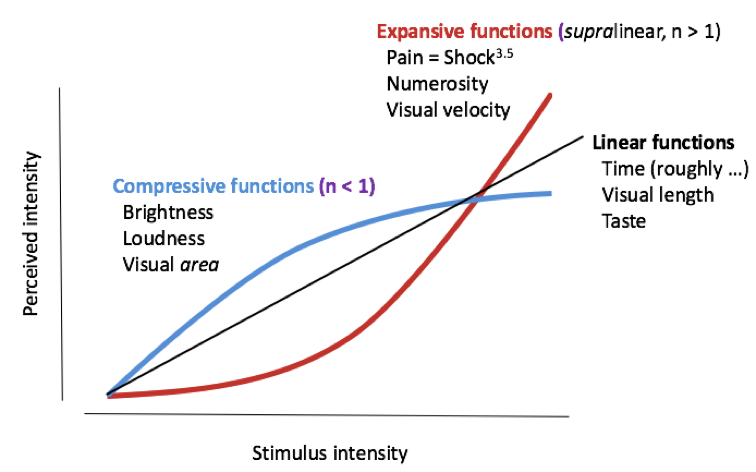

Weber’s law is approximately true for many of our senses—for brightness perception, visual contrast perception, loudness perception, and visual distance estimation, our sensitivity to change decreases as the stimulus gets bigger or stronger. However, there are many senses for which the opposite is true: our sensitivity increases as the stimulus increases. With electric shock, for example, a small increase in the size of the shock is much more noticeable when the shock is large than when it is small. A psychophysical researcher named Stanley Smith Stevens asked people to estimate the magnitude of their sensations for many different kinds of stimuli at different intensities, and then tried to fit lines through the data to predict people’s sensory experiences (Stevens, 1967). What he discovered was that most senses could be described by a power law of the form

P ∝Sn

where P is the perceived magnitude, ∝ means “is proportional to”, S is the physical stimulus magnitude, and n is a positive number. If n is greater than 1, then the slope (rate of change of perception) is getting larger as the stimulus gets larger, and sensitivity increases as stimulus intensity increases. A function like this is described as being expansive or supra-linear. If n is less than 1, then the slope decreases as the stimulus gets larger (the function “rolls over”). These sensations are described as being compressive. Weber’s Law is only (approximately) true for compressive (sublinear) functions; Stevens’ Power Law is useful for describing a wider range of senses.

Both Stevens’ Power Law and Weber’s Law are only approximately true. They are useful for describing, in broad strokes, how our perception of a stimulus depends on its intensity or size. They are rarely accurate for describing perception of stimuli that are near the absolute detection threshold. Still, they are useful for describing how people are going to react to normal everyday stimuli.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Psychology Chapter 5.1 Sensation and Perception.

Provided by: Rice University.

Download for free at https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@12.2:K-DZ-03P@12/5-1-Sensation-versus-Perception.

License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

Galanter, E. (1962). Contemporary Psychophysics. In R. Brown, E.Galanter, E. H. Hess, & G. Mandler (Eds.), New directions in psychology. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Kunst-Wilson, W. R., & Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Affective discrimination of stimuli that cannot be recognized. Science, 207, 557–558.

Nelson, M. R. (2008). The hidden persuaders: Then and now. Journal of Advertising, 37(1), 113–126.

Okawa, H., & Sampath, A. P. (2007). Optimization of single-photon response transmission at the rod-to-rod bipolar synapse. Physiology, 22, 279–286.

Radel, R., Sarrazin, P., Legrain, P., & Gobancé, L. (2009). Subliminal priming of motivational orientation in educational settings: Effect on academic performance moderated by mindfulness. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(4), 1–18.

Rensink, R. A. (2004). Visual sensing without seeing. Psychological Science, 15, 27–32.

Stevens, S. S. (1957). On the psychophysical law. Psychological Review 64(3):153—181. PMID 13441853

Learning Objectives

Be able to diagnose whether a given experiment measures an absolute threshold, a difference threshold, or is a magnitude estimation experiment

Be able to describe a couple of different methods of estimating a threshold

Know what a subliminal message is

Know Weber’s law (also called Weber-Fechner law)

Scientists who study sensation and perception often use psychophysical techniques in their research methods. Psychophysical methods look at a person's (psychological) response to a physical stimulus. In other words, how does a physical change in a stimulus affect a person's perception of it? Psychophysics helps build a bridge between the physical world and our experience of it. Psychophysical methods can help us to determine how loud a sound needs to be before we can hear it or how much sugar needs to be added to a cup of coffee to make it noticeably sweeter, in other words how sensitive we are to different types of stimuli. Psychophysical methods typically measure people's sensitivity in terms of thresholds. For example, you might describe yourself as someone who is highly sensitive to pain - in other words you have a low threshold for pain.

We can measure different types of thresholds in sensation and perception, but let's begin with the concept of an absolute threshold. An absolute threshold is the minimum amount of stimulus energy that must be present for a person to detect a stimulus. Another way to think about this is by asking how dim can a light be or how soft can a sound be for us to be aware of it The sensitivity of our sensory receptors can be quite amazing. It has been estimated that on a clear night, the most sensitive sensory cells in the back of the eye can detect a candle flame 30 miles away (Krisciunas & Carona, 2015) . https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06270

Absolute thresholds are generally measured under incredibly controlled conditions in situations that are optimal for sensitivity. There are three common techniques for measuring thresholds.

- Method of Limits. First, the experimenter presents a series of stimuli of gradually increasing (ascending) intensity until the observer detects the stimulus. In the example below, the brightness of a light starts off very low (luminance = 1 unit) and then is very gradually increased a little at a time (like going up a staircase) until the observer says they can just see it (in the example below this is at 29 units). The threshold on this staircase is estimated to be halfway between the last "no" response (22 units) and the first "yes" response (29 units) i.e., 25.5 units of luminance. This is also called the cross-over point. The ascending trial is followed by a descending trial. In the descending staircase, the light starts off bright (50 units) and is gradually decreased in intensity until the observer says they can no longer see it (15 units). The cross-over point on this staircase is between the last "yes" response - 22 units and the "no" response (15 units). It is quite common to have higher thresholds on ascending compared to descending staircases. This is thought to be due to errors of habituation - we get into a "routine" or a habit of giving the same response. In ascending staircases, the habitual response is a no -- this means we tend to go past the actual threshold before we change to a yes response. The opposite is true for descending trials. One way to try and compensate for these errors is to use multiple and equal numbers of ascending and descending staircases and then calculate the average of the thresholds across all the staircases. When we use the Method of Limits we also use different starting points on each staircase type to avoid the participant trying to guess when they should change their response - based on the previous staircases. This helps us to avoid these errors of anticipation. For example, we might start the first ascending staircase on 1 unit of luminance but the second one (2A) on 8 units.

-

Luminance Ascending staircase (1 A) Descending staircase (1 D) Ascending staircase (2 A) Descending staircase (2 D) 50 Yes 43 Yes Yes 36 Yes Yes 29 Yes Yes Yes 22 No Yes Yes Yes 15 No No No Yes 8 No No No 1 No Cross-over point 25.5 18.5 18.5 11.5

- Method of Adjustment. This is very much like the Method of Limits, except the experimenter gives the observer the knob: "adjust the stimulus until it's very visible" or "adjust the color of the patch until it matches the test patch."

- Method of Constant Stimuli. This is the most reliable, but most time-consuming. You decide ahead of time what levels you are going to measure, do each one a fixed number of times, and record % correct (or the number of detections) for each level. If you randomize the order, you can get rid of bias.

Sometimes, we are more interested in how much difference in stimuli is required to detect a difference between them. This is known as the just noticeable difference (JND) or difference threshold. Unlike the absolute threshold, the difference threshold changes depending on the stimulus intensity. As an example, imagine yourself in a very dark movie theater. If an audience member were to receive a text message on her cell phone which caused her screen to light up, chances are that many people would notice the change in illumination in the theater. However, if the same thing happened in a brightly lit arena during a basketball game, very few people would notice. The cell phone brightness does not change, but its ability to be detected as a change in illumination varies dramatically between the two contexts. Ernst Weber proposed this theory of change in difference threshold in the 1830s, and it has become known as Weber’s law: the difference threshold is a constant fraction of the original stimulus, as the example illustrates.

Weber’s law is approximately true for many of our senses—for brightness perception, visual contrast perception, loudness perception, and visual distance estimation, our sensitivity to change decreases as the stimulus gets bigger or stronger. However, there are many senses for which the opposite is true: our sensitivity increases as the stimulus increases. With electric shock, for example, a small increase in the size of the shock is much more noticeable when the shock is large than when it is small. A psychophysical researcher named Stanley Smith Stevens asked people to estimate the magnitude of their sensations for many different kinds of stimuli at different intensities, and then tried to fit lines through the data to predict people’s sensory experiences (Stevens, 1967). What he discovered was that most senses could be described by a power law of the form

P ∝Sn

where P is the perceived magnitude, ∝ means “is proportional to”, S is the physical stimulus magnitude, and n is a positive number. If n is greater than 1, then the slope (rate of change of perception) is getting larger as the stimulus gets larger, and sensitivity increases as stimulus intensity increases. A function like this is described as being expansive or supra-linear. If n is less than 1, then the slope decreases as the stimulus gets larger (the function “rolls over”). These sensations are described as being compressive. Weber’s Law is only (approximately) true for compressive (sublinear) functions; Stevens’ Power Law is useful for describing a wider range of senses.

Both Stevens’ Power Law and Weber’s Law are only approximately true. They are useful for describing, in broad strokes, how our perception of a stimulus depends on its intensity or size. They are rarely accurate for describing perception of stimuli that are near the absolute detection threshold. Still, they are useful for describing how people are going to react to normal everyday stimuli.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Psychology Chapter 5.1 Sensation and Perception.

Provided by: Rice University.

Download for free at https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@12.2:K-DZ-03P@12/5-1-Sensation-versus-Perception.

License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

Galanter, E. (1962). Contemporary Psychophysics. In R. Brown, E.Galanter, E. H. Hess, & G. Mandler (Eds.), New directions in psychology. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Kunst-Wilson, W. R., & Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Affective discrimination of stimuli that cannot be recognized. Science, 207, 557–558.

Nelson, M. R. (2008). The hidden persuaders: Then and now. Journal of Advertising, 37(1), 113–126.

Okawa, H., & Sampath, A. P. (2007). Optimization of single-photon response transmission at the rod-to-rod bipolar synapse. Physiology, 22, 279–286.

Radel, R., Sarrazin, P., Legrain, P., & Gobancé, L. (2009). Subliminal priming of motivational orientation in educational settings: Effect on academic performance moderated by mindfulness. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(4), 1–18.

Rensink, R. A. (2004). Visual sensing without seeing. Psychological Science, 15, 27–32.

Stevens, S. S. (1957). On the psychophysical law. Psychological Review 64(3):153—181. PMID 13441853

Learning Objectives

Know that infants have full color vision and face perception at birth.

Be able to describe the developmental changes of depth perception and object perception.

Vision is the most poorly developed sense at birth. Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 16 inches away from their faces (which is about the distance from the newborn’s face to the mother/caregiver when an infant is breastfeeding/bottle-feeding). When viewing a person’s face, newborns do not look at the eyes the way adults do; rather, they tend to look at the chin—a less detailed part of the face.

Newborns have difficulty distinguishing between colors, but within a few months they are able to discriminate between colors as well as adults do.

Due to their poor visual acuity, infants look longer at checkerboards with larger squares rather than the boards with many smaller squares. This behavior can actually be observed in a lab setting through eye tracking experiments. Eye tracking is when an observer tracks the gaze of an individual and is sometimes accompanied by measuring the amount of time during which that individual spends looking at one visual stimulus versus another. Thus, toys for infants are sometimes manufactured with black and white patterns rather than pastel colors because the higher contrast between black and white makes the pattern more visible to the immature visual system (Fig.11.2.1).

Despite newborns having some difficulty distinguishing different colors, they are able to view the full color spectrum and are also able to perceive faces, which is of developmental importance. Newborns are mainly focused on bright lights and sensitivity. 2-4 month-olds will begin to follow moving objects as visual coordination improves, and the eyes begin to work together. 5-8 month-olds start to gain depth perception and are able to understand that the world around them is 3-D. A baby’s vision is well-developed by 9–12 months.

By two or three months, they will seek more detail when exploring an object visually and begin showing preferences for unusual images over familiar ones, for patterns over solids, for faces over patterns, and for three-dimensional objects over flat images. Sensitivity to binocular depth cues, which require inputs from both eyes, is evident by about three months and continues to develop during the first six months. By six months, the infant can perceive depth perception in pictures as well (Sen, Yonas, & Knill, 2001). Infants who have experience crawling and exploring will pay greater attention to visual cues of depth and modify their actions accordingly (Berk, 2007).

Open Textbook Library, Child Growth and Development.

Provided by: College of the Canyons

URL: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/child-growth-and-development.

License: CC-BY 4.0

Learning Objectives

Know that infants have full color vision and face perception at birth.

Be able to describe the developmental changes of depth perception and object perception.

Vision is the most poorly developed sense at birth. Newborns typically cannot see further than 8 to 16 inches away from their faces (which is about the distance from the newborn’s face to the mother/caregiver when an infant is breastfeeding/bottle-feeding). When viewing a person’s face, newborns do not look at the eyes the way adults do; rather, they tend to look at the chin—a less detailed part of the face.

Newborns have difficulty distinguishing between colors, but within a few months they are able to discriminate between colors as well as adults do.

Due to their poor visual acuity, infants look longer at checkerboards with larger squares rather than the boards with many smaller squares. This behavior can actually be observed in a lab setting through eye tracking experiments. Eye tracking is when an observer tracks the gaze of an individual and is sometimes accompanied by measuring the amount of time during which that individual spends looking at one visual stimulus versus another. Thus, toys for infants are sometimes manufactured with black and white patterns rather than pastel colors because the higher contrast between black and white makes the pattern more visible to the immature visual system (Fig.11.2.1).

Despite newborns having some difficulty distinguishing different colors, they are able to view the full color spectrum and are also able to perceive faces, which is of developmental importance. Newborns are mainly focused on bright lights and sensitivity. 2-4 month-olds will begin to follow moving objects as visual coordination improves, and the eyes begin to work together. 5-8 month-olds start to gain depth perception and are able to understand that the world around them is 3-D. A baby’s vision is well-developed by 9–12 months.

By two or three months, they will seek more detail when exploring an object visually and begin showing preferences for unusual images over familiar ones, for patterns over solids, for faces over patterns, and for three-dimensional objects over flat images. Sensitivity to binocular depth cues, which require inputs from both eyes, is evident by about three months and continues to develop during the first six months. By six months, the infant can perceive depth perception in pictures as well (Sen, Yonas, & Knill, 2001). Infants who have experience crawling and exploring will pay greater attention to visual cues of depth and modify their actions accordingly (Berk, 2007).

Open Textbook Library, Child Growth and Development.

Provided by: College of the Canyons

URL: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/child-growth-and-development.

License: CC-BY 4.0