Chapter 3: Visual Pathways

3.5. What and Where Pathways

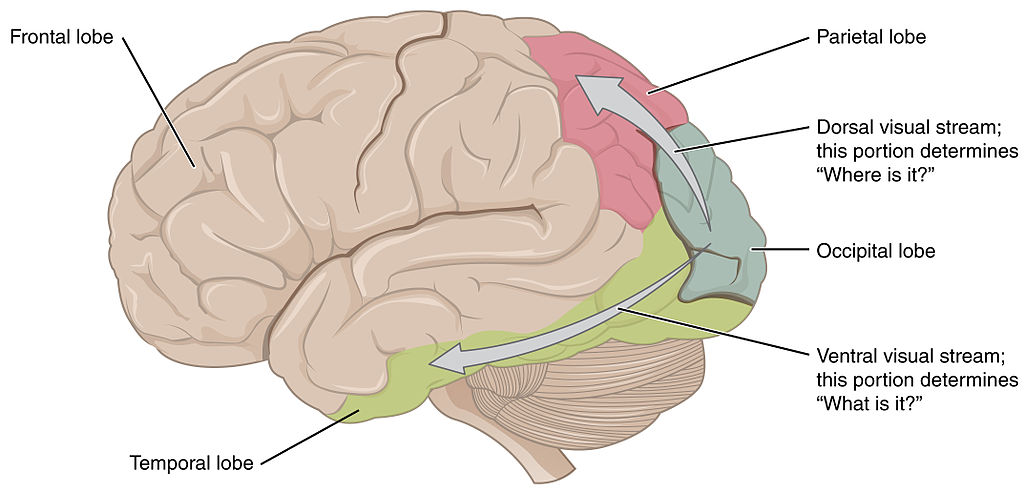

Visual information is processed in many parts of the brain. There are two major visual pathways from the occipital cortex — the ventral pathway, which includes V1, V2, V4, and further regions in inferior temporal areas, is thought to be responsible for object identity i.e., a ‘what’ pathway and the the dorsal stream, which includes V1, V2, V3, V5, supports detection of location and visually-controlled movements (e.g., reaching for an object), i.e., a ‘where’ pathway (Figure 3.7). There are two main types of ganglion cells — magnocellular and parvocellular. Magnocellular cells process information related to movement and about low spatial frequencies and these tend to serve the Where-and-How pathway. In contrast, parvocellular ganglion cells process information about color and small details and tends to supply the What pathway.

- The fusiform face area specializes in identifying whole objects like faces.

- The extrastriate and fusiform body areas help us recognize and anticipate the motions of human bodies (Amoruso et al, 2011).

- The superior temporal sulcus houses many specialized regions related to language and social processing, with a posterior section that is specialized for the recognition of biological motion (Herrington et al, 2011).

- There is even a brain region specialized in letter and word processing called with visual word form area (see Figure 3.8). The visual word form area (VWFA) is a functional region of the left fusiform gyrus and surrounding cortex (right-hand side being part of the fusiform face area) that is hypothesized to be involved in identifying words and letters from lower-level shape images, prior to association with phonology or semantics. Because the alphabet is relatively new in human evolution, it is unlikely that this region developed as a result of selection pressures related to word recognition per se; however, this region may be highly specialized for certain types of shapes that occur naturally in the environment and are therefore likely to surface within written language

Face Perception

Faces are very important to human beings. They provide rich information about people, including their identity, emotions, and we often judge people based on their attractiveness. When face recognition fails, it can have serious consequences. It often seems effortless for us to recognize the faces of the people that we know and love, but there is a condition known as prosopagnosia — or face blindness, where people cannot recognize other people’s faces. Imagine being a prosopagnosic parent trying to identify their child at school pick-up (Oruc et al. 2019).

However, research shows that even people with normal face perception have difficulties recognizing different photos of the same person if they are unfamiliar to them. When given multiple photos of unfamiliar faces, people often identify photos of the same person as different people. However, they do well recognizing different photos of people that they know well (Jenkins et al., 2011).

Face perception is highly dependent on experience. This is demonstrated by a phenomenon called the other-race (or cross-race) effect, which is the reduced ability to recognize the faces of people from a race other than our own (Kelly et al., 2007). This effect begins in infancy through “perceptual narrowing,” where babies lose the ability to distinguish faces from racial groups they rarely encounter (Kelly et al., 2007). Both infants and adults spend substantial time viewing faces, but limited exposure to diverse faces can impair recognition abilities (Balas & Saville, 2017). Most studies looking at the cross-race effect have focused on White participants, however, in one study, Lee and Penrod found that participant race determines the extent of the cross-race effect. White participants showed larger cross-race effects than Asian participants. However, Asian, White, and Latinx participants all showed larger cross-race effects for Black faces compared to faces of other races (Lee & Penrod, 2022). In other words, people who are not Black, have more difficulty recognizing Black faces than White, Asian or Latinx faces. Poorer recognition of Black faces has widespread societal implications, ranging from hurtful classroom interactions where Black students are mistaken for other students (Griffith et al., 2019), to the increased rates of misidentification of Black people by people witnessing crimes and misdemeanors (Lee & Penrod, 2022). However, research by McKone et al. (2019) offers hope for addressing these issues. They found that exposure to faces of different races before the age of 12 years can help mitigate the cross-race effect. This suggests that by promoting diversity and inclusivity from a young age, we can work towards a future where BIPOC individuals experience less discrimination.

As we have already seen, faces are processed within a specialized area of the visual system called the fusiform face area. This area is in the ventral stream of the right hemisphere in the inferior temporal lobe. Unlike other objects, if we turn a face upside down it makes it much more difficult to recognize (face inversion effect; Yin, 1969). This is because face perception depends on using holistic or configural processing, where we take into account the relative distances between our facial features (eyes, nose, mouth etc). Being able to engage in configural processing also allows for more efficient processing compared to other objects. Other brain areas are also important for face perception. The amygdala is activated by emotional facial expressions and the superior temporal sulcus, helps us to detect biological motion, including eye and mouth movements (Allison et al., 2000).

Blindsight

We previously mentioned that there is also a subcortical pathway that visual information can take through the brain. In fact there are several different subcortical structures that receive visual information but one of the main ones is a structure call the superior colliculus. The superior colliculus sits just above the inferior colliculus, on the surface of the midbrain. Although often overlooked when describing visual processing, the superior colliculus is thought to be involved in localisation and motion coding. It has also been implicated in an interesting phenomenon termed Blindsight (see Box below, Blindsight: I am blind and yet I see).

Blindsight: I am blind and yet I see

Blindsight was first described in the 1970s by researchers who had identified residual visual functioning in individuals who were deemed to be clinically blind due to damage to the visual cortex (Pöppel, Held, & Frost, 1973; L Weiskrantz & Warrington, 1974). These individuals reported being unable to see, but could detect, localize or discriminate stimuli that they were unaware of more reliably than if they were just guessing. Later work allowed a further distinction to be made into blindsight Type 1, where the individual could guess certain features of the stimulus e.g., type of motion, without any conscious awareness of it, and Type 2 where individuals could detect a change in the visual field but cannot describe the type of change (L. Weiskrantz, 1997).

Several explanations have been proposed for this interesting phenomenon:

- Areas other than primary visual cortex underlie the responses, including the superior colliculus, which has been shown to provide quick crude responses to visual stimuli.

- Whilst much of the primary visual cortex is destroyed in people with blindsight, small pockets of functionality remain, and this explains the residual abilities.

- The LGN is capable for detecting key visual information and passing this directly to other cortical areas which could explain the phenomenon.

Research continues into blindsight and the role of several brain structures in visual processing, but the existence of this phenomenon has demonstrated that subcortical pathways and structures outside the primary visual cortex can still play a significant role in visual processing.