Chapter 8. Culture and Vision

8.3. Industrialization and Susceptibility to Optical Illusions

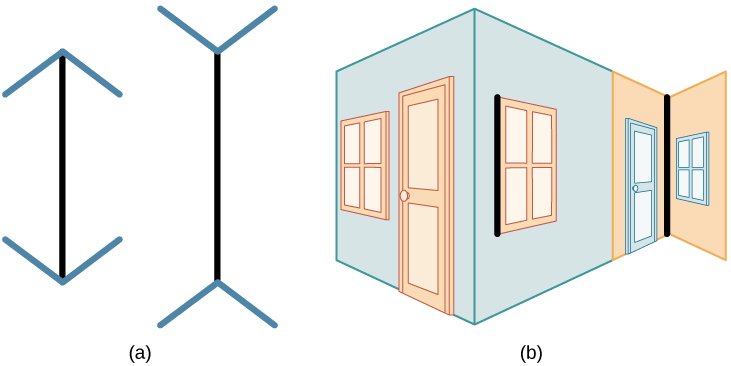

Culture can also affect our susceptibility to visual illusions. Marshall and colleagues conducted a multi-national study in which they found that individuals from industrialized cultures were more prone to experience certain types of visual illusions than individuals from non-industrialized cultures (Marshall et al., 1963). Westerners are more likely to experience the Müller-Lyer illusion than people living in non-industrialized countries (Figure 8.5). In the illusion, the two black lines in Figure 8.5a appear to be different lengths, but they are actually the same. This illusion also applies to the lines in Figure 8.4b.

Early research by Rivers before 1922 found that Murray Islanders showed no evidence of the illusion. Later, Segall et al. (1966) demonstrated that while US participants (including children, students, and adults in Illinois) showed strong susceptibility to the illusion, Kalahari Bushmen and South African miners showed no such effect. These findings led to the “carpentered world hypothesis,” which suggested that people living in a world built by carpenters with multiple right angles are most susceptible to the illusion. Pederson and Wheeler (1983) tested the illusion with Navajo participants. They found that those raised in traditional round houses (hogans) showed no illusion, while those raised in rectangular houses were more susceptible.

Similar environmental influences appear in studies of the Ponzo illusion. Brislin (1974) found that participants from Guam, where there are no railroads or long straight roads, showed no effect. Brislin and Keating (1974) demonstrated that urban Filipinos and US participants showed stronger effects than Pacific Islanders from rural areas. Wagner’s 1977 research with Moroccan participants revealed that the effect strengthened with increased education and urban living experience. Presumably, this is because rural environments lack linear perspective as a depth cue, but people who live in urban environments or are exposed to books or films of urban environments often use linear perspective to estimate distance. Similarly, the influence of environment and education on depth perception was also explored in Hudson’s 1960 study of 10 African tribes, which showed that interpretation of depth in 2D images varied with exposure to Western education and urban environments.

Ebbinghaus Illusion

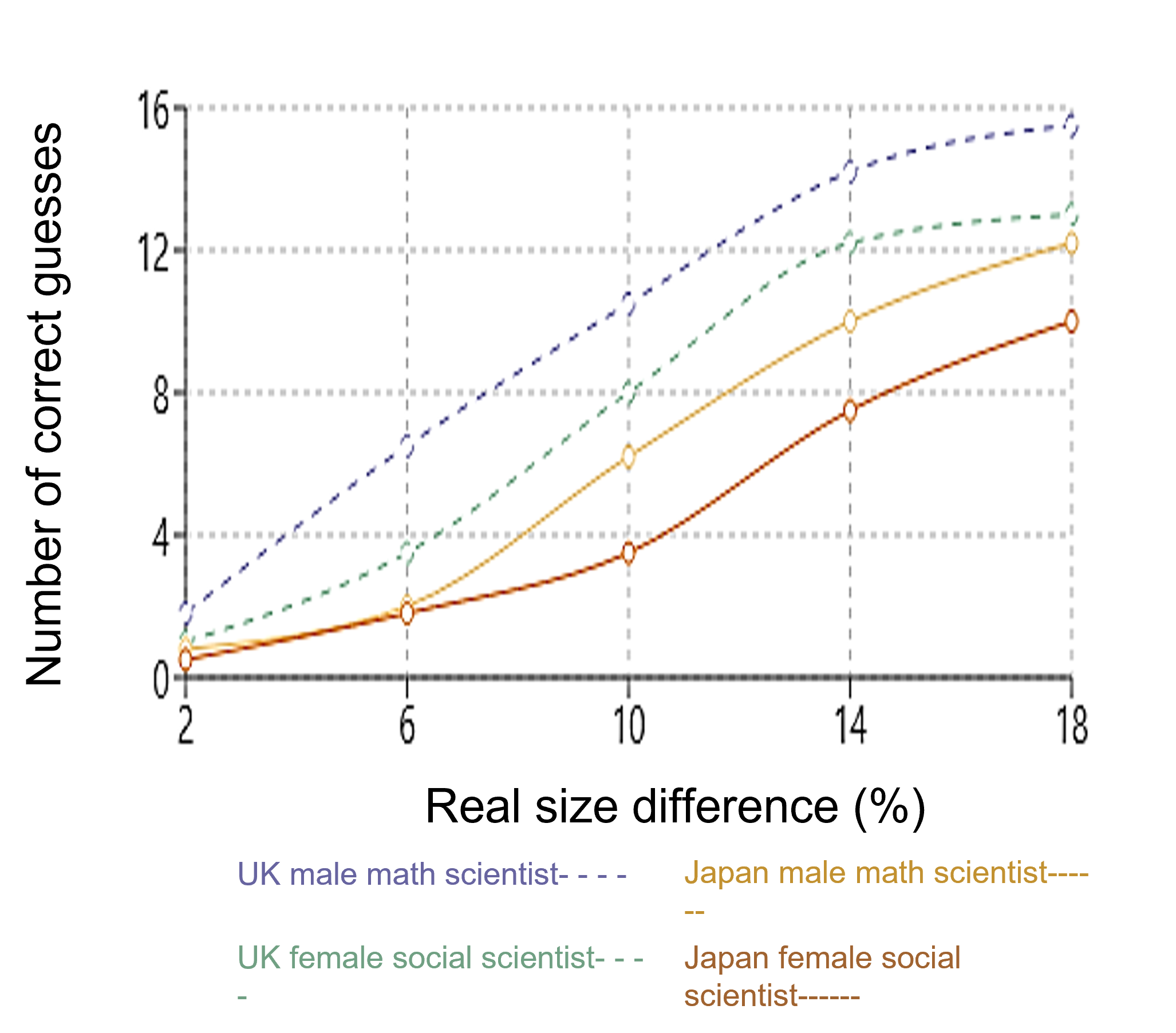

In the Ebbinghaus illusion (see Figure 8.5) we are asked to compare the size of the central circle in each shape. For many of us, the central circle surrounded by the little circles (on the left) appears larger than the central circle surrounded by the larger circles (on the right). In reality, they are both the same size. In other words, we are influenced by the context in which the circle is situated. Doherty et al. (2008) found that size perception was more context-dependent in Japanese than UK students, with male math students showing more context-dependency than female social science students (see Figure 8.6). This effect was linked to V1 activity, suggesting cultural influences on pre-attentive processing.

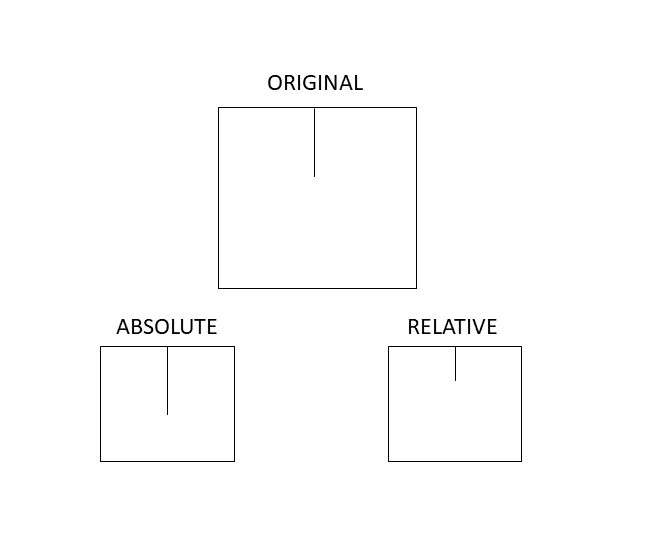

Kitayama et al. (1973) demonstrated systematic differences in absolute versus relative size perception. Participants were asked to do one of two tasks. In the absolute task they had to decide whether the vertical line was the same physical length as the original and in the relative task they had to estimate whether it was the same relative size as the original (see Figure 8.7). Japanese students made more errors on absolute size tasks (tending to underestimate) whereas US students making more errors on relative size tasks (tending toward actual size). These behavioral findings were supported by neuroimaging research. In a follow-up study using the same task, Hedden et al. (2008) used fMRI to show increased frontal and parietal cortex activity when participants performed tasks that didn’t align with their cultural preferences. Japanese participants showed increased attention for absolute line tasks, while US participants showed increased attention for relative line tasks.

This chapter was written by Jill Grose-Fifer, Ph.D. Portions of it appear in:

Grose-Fifer, J., Spielman, R. M., Dumper, K., Jenkins, W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perlmutter, M. (2021). Introduction to Psychology (A critical approach). CUNY Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/jjcpsy101/

References

Brislin, R. W. (1974). The Ponzo illusion: Additional cues, age orientation and culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 5(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202217400500201

Caldara, R. (2017). Culture reveals a flexible system for face processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(4), 249-255. 3

https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417710036

Chua, H. F., Boland, J. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (2005). Cultural variation in eye movements during scene perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(35), 12629-12633. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506162102

De Oliveira, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2017). Culture changes how we think about attention. From “human inference” to “geography of thought”. Perspectives on psychological Science, 12(5), 782–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617702718

Doherty, M. J., Tsuji, H., & Phillips, W. A. (2008). The context sensitivity of visual size perception varies across cultures. Perception, 37(9), 1426-1433. https://doi.org/10.1068/p5946

Deręgowski, J. B. (1998). W H R Rivers (1864–1922): The founder of research in cross-cultural perception. Perception, 27(12), 1393–1406. https://doi.org/10.1068/p271393

Hedden, T., Ketay, S., Aron, A., Markus, H. R., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2008). Cultural influences on neural substrates of attentional control. Psychological Science, 19(1), 12-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02038.x

Hudson, W. (1960). Pictorial depth perception in sub-cultural groups in Africa. Journal of Social Psychology, 52, 183-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1960.9922077

Kitayama, S., Duffy, S., Kawamura, T., & Larsen, J. T. (1973). Perceiving an object and its context in different cultures: A cultural look at new look. Psychological Science, 14(3), 201-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.02432

Masuda, T., & Nisbett, R. E. (2006). Culture and Change Blindness. Cognitive Science, 30(2), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0000_63

Masuda, T., Ellsworth, P. C., Mesquita, B., Leu, J., Tanida, S., & Van de Veerdonk, E. (2008). Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3), 365-381. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365

Masuda, T., Wang, H., Ishii, K., & Ito, K. (2012). Do surrounding figures’ emotions affect judgment of the target figure’s emotion? Comparing the eye-movement patterns of European Canadians, Asian Canadians, Asian international students, and Japanese. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6, 72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2012.00072

Pederson, D. M., & Wheeler, J. (1983). The Müller-Lyer illusion among Navajos. Journal of Social Psychology, 121, 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1983.9924459

Segall, M. H., Campbell, D. T., & Herskovits, M. J. (1966). The influence of culture on visual perception. Bobbs-Merrill.

https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12490

Ueda, Y., Chen, L., Kopecky, J., Cramer, E. S., Rensink, R. A., Meyer, D. E., Kitayama, S., & Saiki, J. (2018). Cultural differences in visual search for geometric figures. Cognitive Science, 42(1), 286-310.

https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12490

Wagner, D. A. (1977). Ontogeny of the Ponzo illusion: Effects of age, schooling, and environment. International Journal of Psychology, 12(3), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207597708247386