Chapter 2: Light and the Eye

2.2 Eyeball Anatomy

Structure of the Eye

We see things in our environment because light reflects off them and into our eyes. The eye is made up of various components that work together to focus light onto the receptors in the retina at the back of the eye. These components act like the optical parts of a camera and create an image of the world on the retina. The picture it forms is a little odd though – it is upside down and flipped left to right (like looking in a mirror). Let’s take a look at how light travels through the eye to form these pictures (Figure 2.2). Light enters the front of the eye through the cornea, a transparent, curved structure. It does most of the focusing of the eye, but is not flexible and so does not help us to change focus. After passing through the cornea, light then travels through the aqueous humor, a fluid that fills a small chamber behind the cornea, and then through the pupil, which is a hole in the iris (the colored part of the eye). The size of the pupil is determined by the muscles in the iris, which responds to different lighting conditions. The pupil can be dilated (made bigger) or constricted (made smaller) to adjust the amount of light entering the back of the eye. Light next passes through the lens, which also helps us to focus, but for much of our lives it is flexible in shape and so helps us to focus on close objects — like when we are reading a book. The lens changes its shape (curvature) through the contraction and relaxation of ciliary muscles. Light then enters the posterior cavity of the eye, which is filled with a jelly-like substance called the vitreous humor. As we get older, people develop presbyopia because the lens hardens and can’t be moved by the ciliary muscles (a process called accommodation), making it difficult to focus on things that are near. Another relatively common vision problem in the elderly are cataracts, which make the lens cloudy and so less light reaches the photoreceptors.

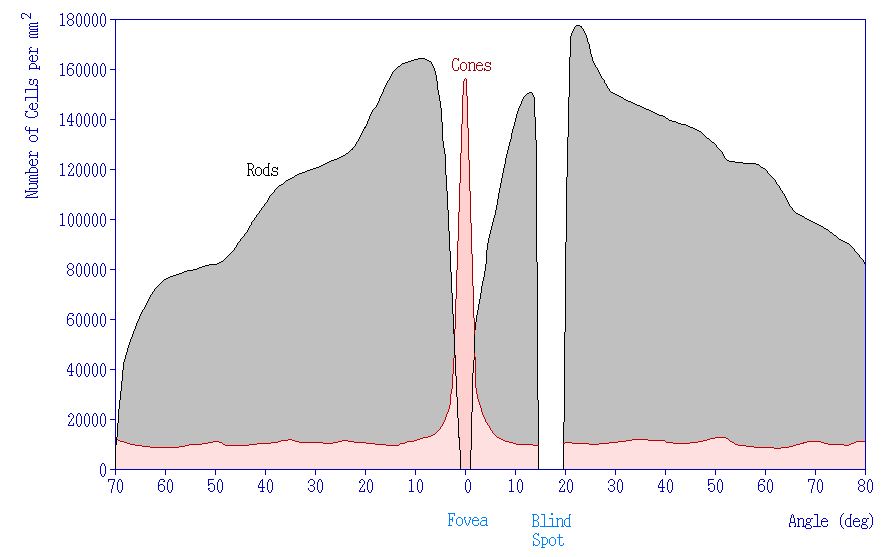

When light finally reaches the retina, a sheet of neurons at the back of the eye, it stimulates the sensory receptors (cones and rods). The rods and cones contain pigments that absorb light when it reaches them, hence they are often referred to as photoreceptors. The photoreceptors transduce (or convert) light into neural signals that are sent to the brain via the optic nerve. The center of the retina contains a tiny area called the fovea, which is densely packed with a very high concentration of cones. This area gives us our best visual acuity (the ability to see very small details) and color vision. When we look at something, we automatically move our eyes so that its image lands on the fovea.

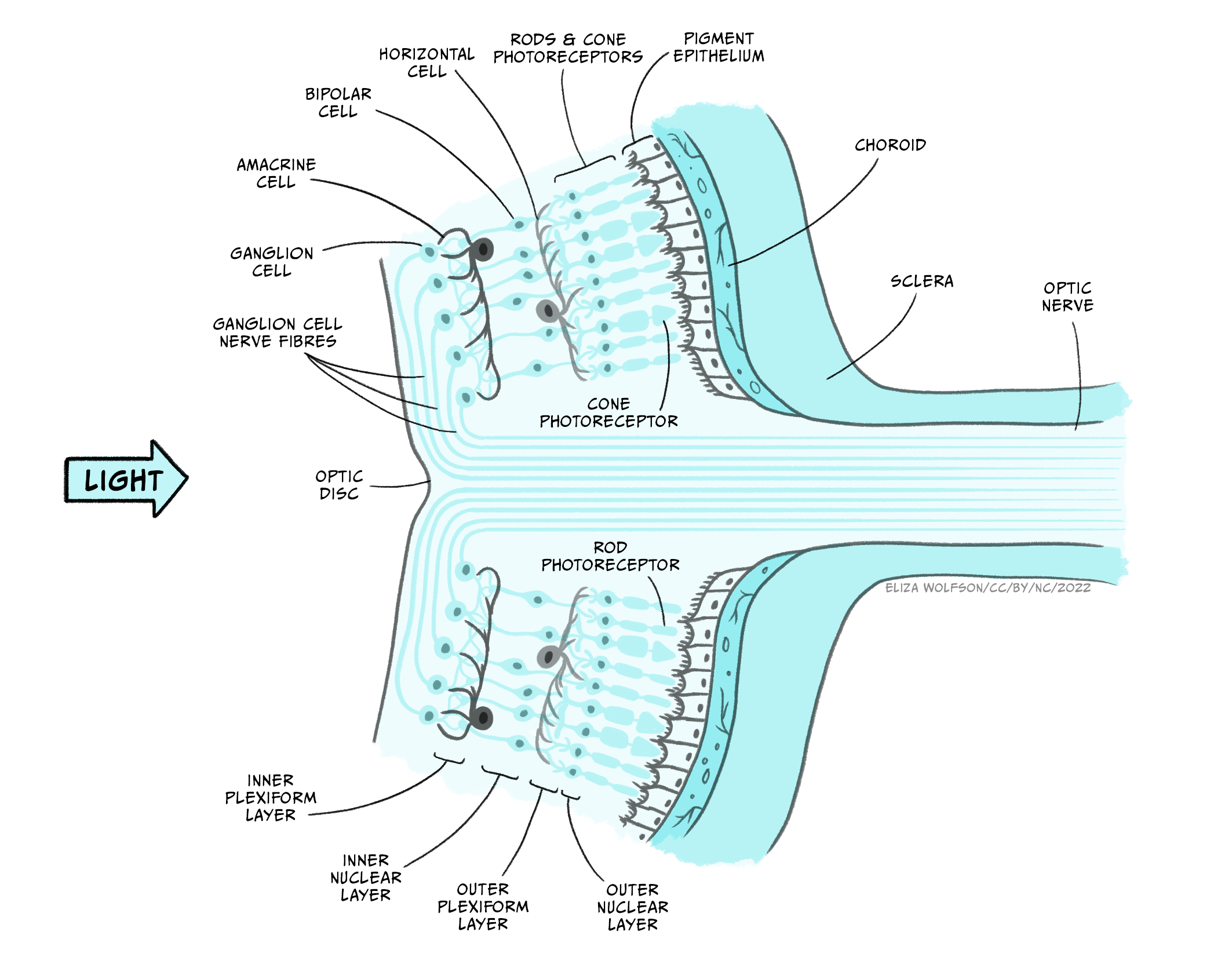

The retina consists of three layers of cells — the photoreceptors pass neural information to the bipolar cells, which send the neural message to the ganglion cells, which transmit information to the brain (see Figure 2.4). The retina is built “inside-out”; light has to travel first through the ganglion cells and bipolar cell layers to reach the photoreceptors, which is why these upper layers of cells are transparent to ensure as much light as possible reaches the receptors. This curious arrangement also ensures that the photoreceptors are attached to a layer of cells called the pigment epithelium where the visual pigments that are regenerated. Behind this, the choroid provides a specialized blood supply to the photoreceptors, which is vital for their functioning. The axons of the ganglion cells make up the optic nerve. The optic nerve brings the messages from the eye to the brain. However, where the axons leave the eye (optic nerve head) there is no space for any photoreceptors. This causes a corresponding blind spot in each eye. Perceptually, the blind spot is hard to notice because our brains automatically “fill in” the missing information without our being aware of it, with a guess based upon what is visible surrounding the blind spot.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Anatomy and Physiology Chapter 14.1 Sensory Perception

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/14-1-sensory-perception

License: CC-BY 4.0

Adapted by: Ran Rice

Cheryl Olman PSY 3031 Detailed Outline

Provided by: University of Minnesota

Download for free at http://vision.psych.umn.edu/users/caolman/courses/PSY3031/

License of original source: CC Attribution 4.0

Adapted by: Ran Rice and Jacob Powers

Dommett, E. (2023). Lighting the world: our sense of vision. In C. Hall (Ed). Introduction to biological psychology. University of Sussex. https://doi.org/10.20919/ZDGF9829