Chapter 1. Psychophysics and Neuroscience.

1.4 How neurons work

Tissue in the nervous system is composed of two main types of cells, neurons and glial cells. Neurons are the primary communication and processing cells. Glial cells play a supporting role for the neurons.

Parts of a Neuron

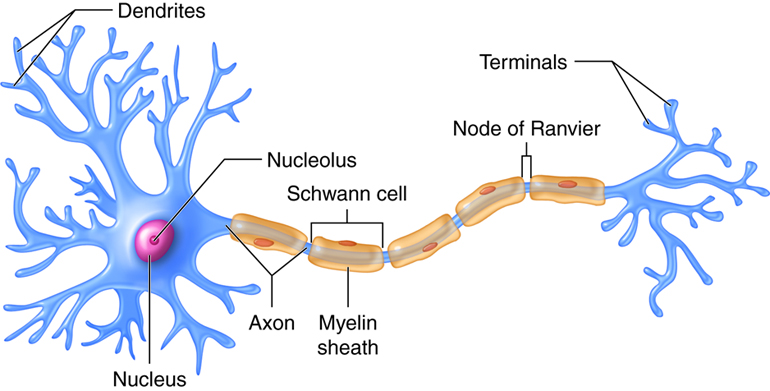

The cell body or soma of the neuron contains the nucleus (which contains the genetic material of the cell), and other structures that are important for cell maintenance. The soma is surrounded by a semipermeable membrane, which regulates what can pass in and out of the neuron. Information enters the neuron through the dendrites, which are branching tree-like projections on the soma. Information is then transmitted to the other end of the neuron down a tail-like process called the axon. Information travels through the neuron in the form of electrical energy. At the end of the axon, there are small structures called terminal buttons which contain chemical messengers called neurotransmitters; these allow the neuron to communicate with other cells (see Figure 1.5).

The length of the axon determines how far one neuron carries information through our bodies, some axons are microscopic while others, like the ones running from our toes to the base of our spine, are several feet long. Many axons are coated with a fatty substance known as the myelin sheath, which acts as an insulator and speeds up the transmission of the electrical signals down the axon. The myelin has small gaps along the axon called the nodes of Ranvier. In myelinated axons, the electrical signals are only generated at the nodes, like a train making express stops. In unmyelinated neurons, information travels more slowly because electrical signals need to be generated along the entire length of the axon—acting more like a local train. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder that causes degeneration of the myelin sheath on axons throughout the nervous system. This can result in inefficient transmission, and sometimes total loss, of neural information. Some of the first symptoms of MS include blurry vision, sensations of numbness (like pins and needles) and difficulty walking.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about neuronal communication to learn more.

Neuronal Communication

Now that we have learned about the basic structures of the neuron, let’s take a closer look at the signals that the neurons transmit. We will look first at how the electrical signals are generated and move through the neuron. Then we will look at how the chemical messengers are released by the neurons and communicate with other cells, including other neurons.

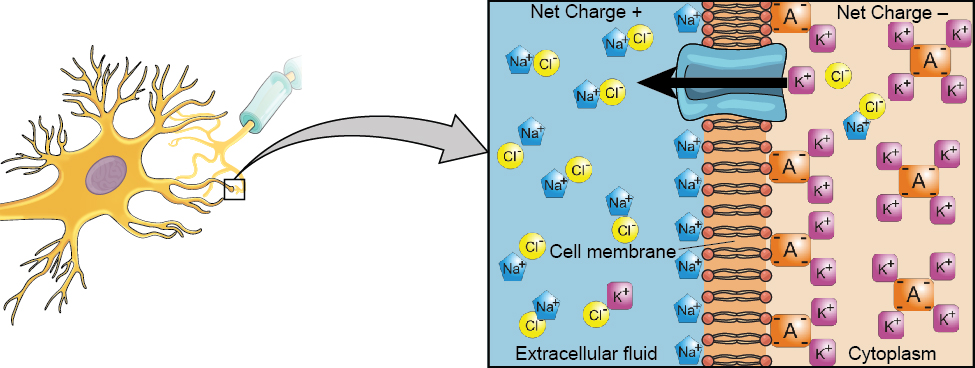

The neuron exists in a fluid environment—it is surrounded by extracellular fluid and contains intracellular fluid. The neuronal membrane keeps these two salty fluids separate. Both fluids contain sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) ions, and other charged molecules. Differences in the overall electrical charge of molecules in the two fluids contribute to a difference in voltage across the membrane, called the membrane potential. When the neuron is resting, the membrane resting potential is about 70 mV and the inside of the neuron is more negatively charged than the outside. In general, ions move quickly across concentration gradients from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration through the process of osmosis. Na+ is at higher concentrations outside the neuron, so it strongly wants to move into the neuron. K+ on the other hand, is more concentrated inside the neuron, and so wants to move out of the neuron (Figure 1.6). Because the inside of the neuron is slightly negatively charged compared to the outside, this provides an additional drive for Na+ to be drawn into the neuron (opposite electrical charges attract). We call this an electrical gradient. However, there is relatively little ionic movement across the membrane when the neuron is resting. This is because most of the Na+ and K+ gates in the semi-permeable membrane, which regulate the flow of ions, are closed when the neuron is at rest. This results in a high state of tension across the membrane; the Na+ and K+ ions are waiting for the gates to open so they can move through them, and so the neuron is primed and ready for action. For the most part, the Na+ and K+ gates do a good job of staying closed, but a few open and there is a little bit of leakage of Na+ and K+ in the direction described above. To keep the resting potential stable, there is an active sodium-potassium pump, which pumps three sodium ions out of the neuron for every two potassium ions in.

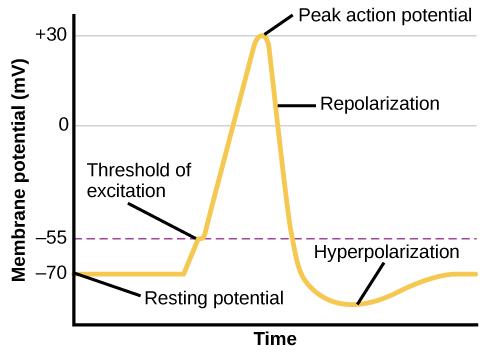

From this resting potential state, if the neuron receives a signal at the dendrites, the Na+ gates open on the neuronal membrane, and Na+ ions rush into the cell. These ions make the inside of the cell become more positively charged. If that charge reaches a certain level, called the threshold of excitation, the neuron becomes active and the action potential begins. The action potential, sometimes called a nerve impulse, is a large, rapid change in voltage across the membrane. (Figure 1.7).

Whether or not the threshold of excitation is reached depends on the strength of the signal being received. When the signal is strong, more Na+ gates open and more Na+ ions enter and the inside of the cell becomes more positive. When the threshold of excitation is reached, all the Na+ channels open rapidly, causing a massive influx of Na+ ions and a huge positive spike in the membrane potential. At the peak of the spike, the Na+ gates close and the K+ gates open. As positively charged potassium ions rapidly leave the neuron, the inside of the cell quickly starts to become less positive (or more negative). This process is called repolarization. After an action potential is generated there is a resting period, called the refractory period, where the inside of the cell is in a state of hyperpolarization. This means that it is slightly more negative than the resting potential for a few milliseconds; it is not possible to generate another action potential during the refractory period. As the K+ gates close, the neuron returns to the resting potential (Figure 1.7).

The action potentials are generated in the cell body first and then are produced along the axon until they reach its end. At each point in the journey, some of the sodium ions that enter the neuron diffuse to the next section of the axon, raising the charge past the threshold of excitation and triggering a new influx of sodium ions. So, multiple action potentials are generated sequentially all the way down the axon until they reach the terminal buttons.

The action potential is an all-or-none phenomenon. In simple terms, this means that an incoming signal from another neuron must be strong enough to reach the threshold of excitation, otherwise, there is no action potential (none). The action potential is always generated at its full strength at every point along the axon. It does not fade away as it travels down the axon. This ensures that there is no loss of information along the way. The size of the action potential does not depend on the strength of the stimulus, it is always the same. Strong stimuli simply produce more action potentials.

In many ways, the way that a neuron produces action potentials is similar to the way that an old fashioned toilet produces a flush. Both work on the all or none principle. A toilet also has a threshold of excitation – if you do not push the handle hard enough, it will not flush. However, as long as you press the handle hard enough, the toilet always produces a flush of the same size. So, you have all or none. If you push very hard, you don’t get any more water than if you push more gently, provided you meet the threshold of excitation. Like a neuron, a toilet also has a refractory period (when the tank is refilling); the toilet cannot flush during this time.

Communication across the synapse

At the end of every axon, there is a tiny gap called a synapse between the terminal buttons and the next cell, which is often another neuron. This gap is filled with extracellular fluid and is too big for an action potential to jump across. Instead, when the action potential arrives at the terminal button, small vesicles release their neurotransmitters into the synapse. The neurotransmitters travel across the synapse and bind to receptors on the dendrites of the adjacent neuron (see Figure 1.8). This action then affects the ionic gates in that neuron. Some neurotransmitters are excitatory (they open Na+) gates, whereas others are inhibitory (they open K+) gates. So, neurotransmitters give more flexibility in terms of how neurons can respond to a stimulus.

This module was edited by Jill Grose-Fifer, PhD. Some of this material for this chapter has come directly or has been modified slightly from the following open access educational resources (OERs).

Crump, M. J. C., Price, P.C., Jhangiani, R., Chiang, I-C.A., Leighton, D.C. (2017). Research methods for psychology. Retrieved from https://crumplab.com/ResearchMethods/

Price, P.C., Jhangiani, R., Chiang, I-C.A. (2015). Research methods in psychology (2nd edition). Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/researchmethods/

Scollon, C. N. (2023). Research designs. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/acxb2thy

Spielman, R. M., Dumper, K., Jenkins W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perlmutter, M. (2014). Psychology (2nd edition). Open Stax. Retrieved from https://openstax.org

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Anatomy and Physiology Section 12.2 Nervous Tissue

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

License: CC-BY 4.0

Adapted by: Cheryl Olman