Chapter 4: Object Recognition

4.1. Perception is Ambiguous

The Challenges of Visual Perception

Our visual system faces several fundamental challenges when interpreting the world around us. While we effortlessly perceive a three-dimensional world, our eyes actually receive only two-dimensional images on their retinas. The brain must then transform these flat images into our rich perception of depth, shape, and movement. This transformation process is complex and sometimes ambiguous, which helps explain why creating computer vision systems that match human capabilities remains difficult.

Let’s explore some key examples of perceptual ambiguity:

Figure-Ground Separation

When looking at a scene, our brain needs to determine which elements belong to objects (the figure) and which belong to the background. This process involves both simple visual features like edges and textures, as well as more complex interpretations of object shapes and how the scene is arranged.

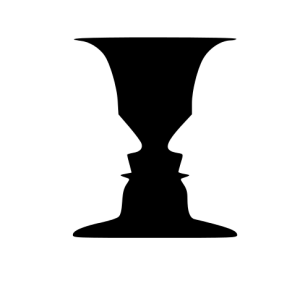

Bistable Images

Some images can be interpreted in two equally valid ways, such as the classic vase-faces illusion shown in Figure 4.1. When you look at this image, you might first see a black vase against a white background, then suddenly perceive two white faces looking at each other against a black background. Your perception may switch back and forth between these interpretations because your brain has equal evidence for both. This switching occurs when neither interpretation “wins out” in the early visual processing areas of your brain.

The Aperture Problem

When viewing motion through a small opening (or aperture), our visual system faces an interesting challenge. A moving line segment seen through such an opening could be interpreted as moving in different directions – what we perceive as horizontal motion might actually be vertical, or vice versa. This demonstrates how limited information can lead to multiple possible interpretations of movement.

Light and Shape Perception

Our brain makes certain assumptions about lighting to help interpret the shapes we see:

- We typically assume light comes from above, casting shadows below objects. This assumption helps us interpret bumps and dips in surfaces – a circle that’s lighter on top and darker below tends to look like a bump, while the reverse pattern appears as a depression.

- Our perception of an object’s shape, its surface properties, and the lighting conditions are all interconnected. For instance, how we interpret the three-dimensional shape of an object depends on both its shading patterns and our assumptions about the direction of light.

Visual Degradation

We often need to identify objects in less-than-ideal viewing conditions. This might occur when:

- Looking through a rain-streaked window or foggy windshield

- Viewing objects without proper vision correction (glasses or contact lenses)

- Seeing things in poor lighting conditions or at great distances.

In these situations, our brain compensates for the degraded visual input by using context and prior knowledge. For instance, you can often recognize a friend approaching even through heavy rain because your brain combines the blurry visual information with your knowledge of how they typically walk and dress.

Occlusion

Objects in the real world frequently overlap or partially hide one another. When this happens, we only see fragments of the hidden object, yet we can often recognize it successfully. This ability relies on several processes:

- Object completion: Our brain fills in the missing parts based on our knowledge of typical object shapes

- Pattern recognition: We can identify objects from visible portions even when key features are hidden

- Context: The surrounding environment provides clues about what the partially hidden object might be For example, if you see just the tail and back legs of an animal behind a fence, you might still recognize it as a cat based on these visible parts and the context of being in a residential garden.

Viewpoint Dependence

Objects in the three-dimensional world can look dramatically different depending on our viewing angle. Consider how a coffee cup appears from different perspectives (Figure 4.2).

Despite these varying appearances, we maintain a consistent mental representation of the object. This ability to recognize objects across different viewpoints develops through experience and involves building mental models that incorporate multiple possible views of the same object.

This last set of challenges further illustrates why computer vision systems, which must be explicitly programmed to handle these variations, still struggle to match human performance in object recognition under real-world conditions.

Cheryl Olman PSY 3031 Detailed Outline

Provided by: University of Minnesota

Download for free at http://vision.psych.umn.edu/users/caolman/courses/PSY3031/

License of original source: CC Attribution 4.0