Chapter 3: Visual Pathways

3.1. Visual Pathways

Visual pathways: to the visual cortex and beyond

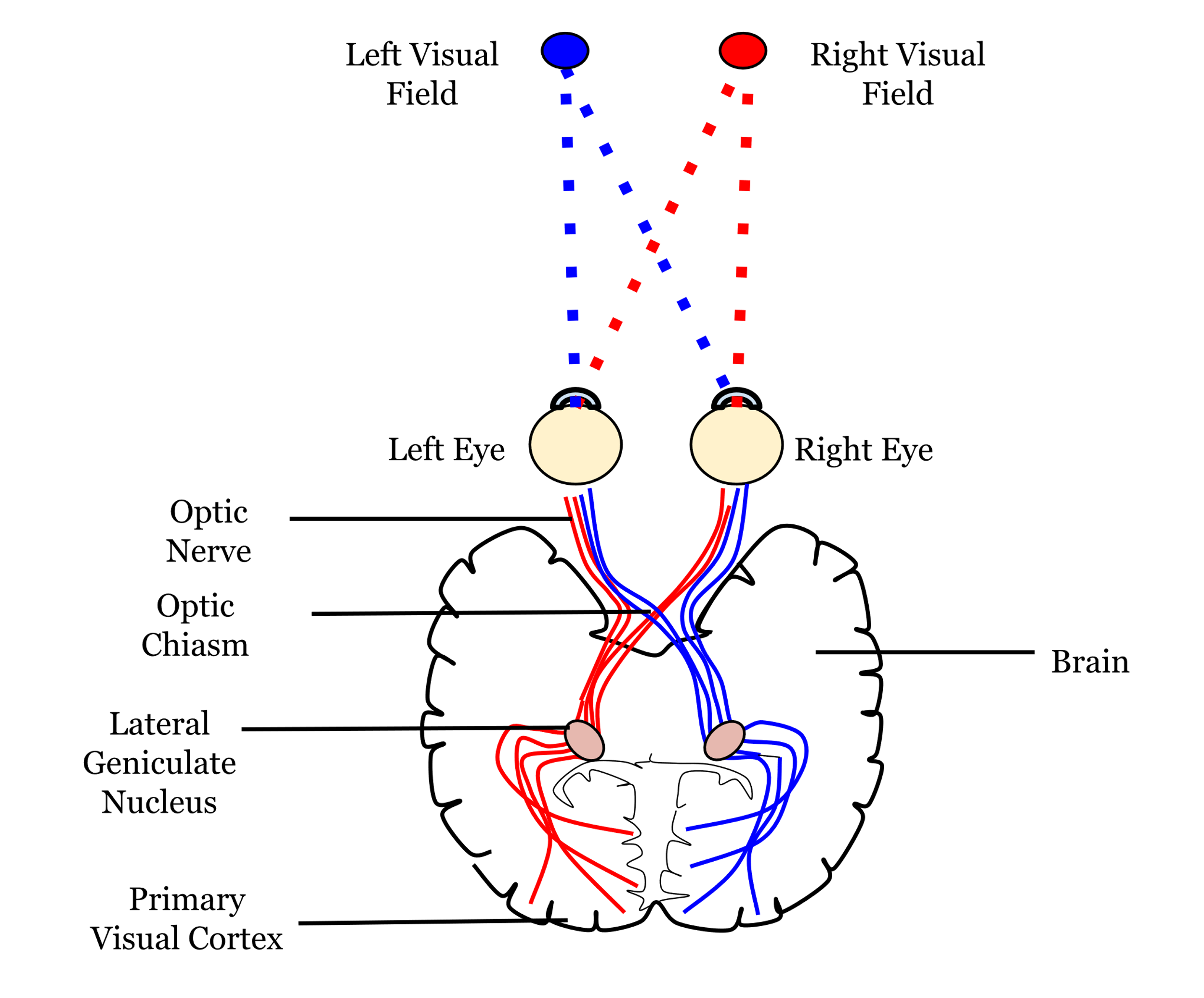

The axons of the retinal ganglion cells form the optic nerve and leave the eye through the blind spot. From the optic nerve, two routes that can be taken, either a cortical or a subcortical route. The cortical route is the pathway that is responsible for much of our higher processing of visual information and has been the focus of a large amount of research. Figure 3.1 shows the route that visual information typically takes from the eye to the primary visual cortex, located in the occipital lobe.

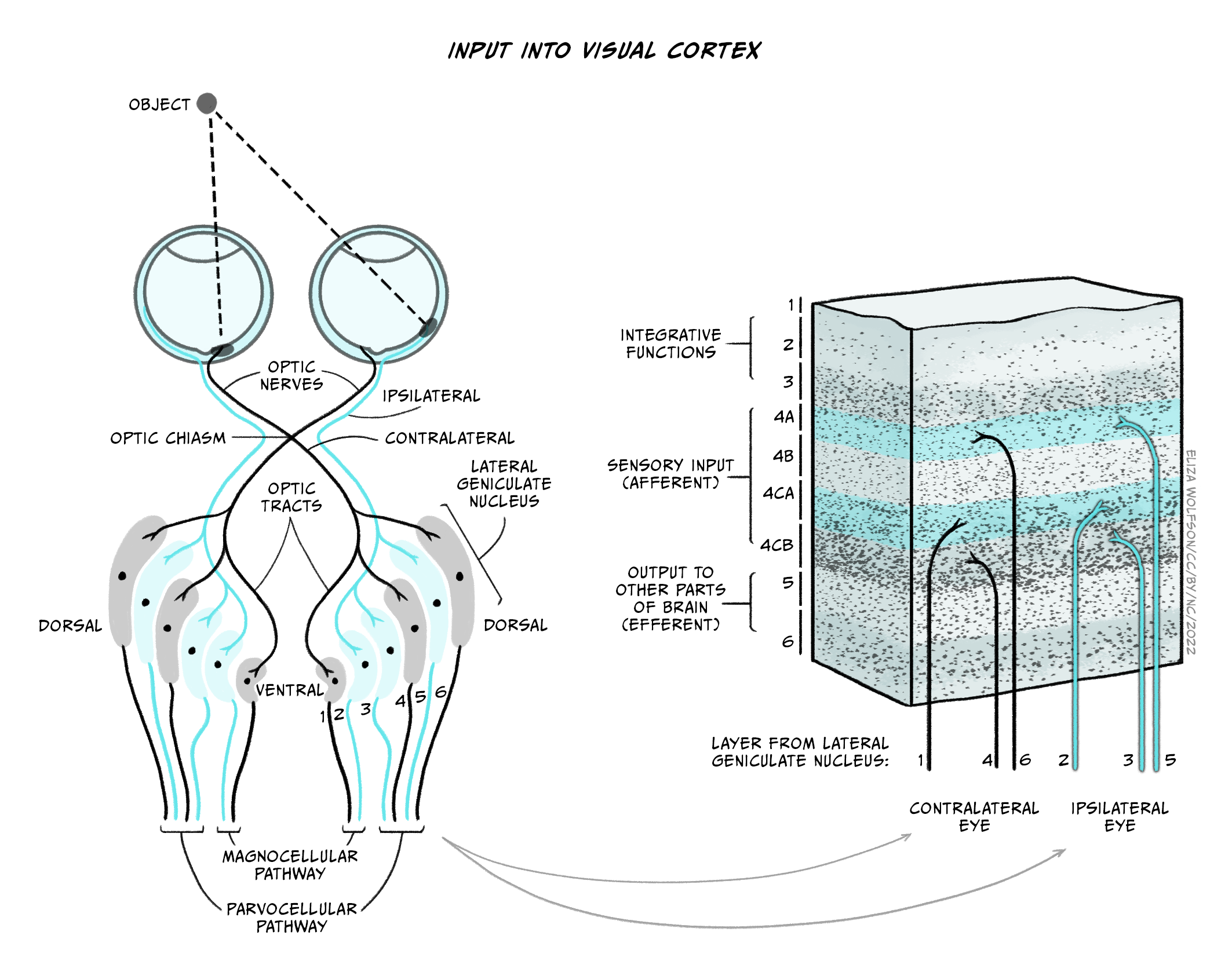

Starting from the eye, information leaves via the optic nerve. The optic nerves from both eyes meet at the optic chiasm which can be seen on the underside of the brain (Figure 3.1). At this point, information is arranged such that signals from the left visual field of both eyes continues its pathway via the right side of the brain, whilst information from the right visual field of both eyes travels onwards in the left side of the brain. The first stop in the brain is the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) which is part of the thalamus. Each LGN is divided into six layers. Three of these layers receive information from one eye and three receive it from the other. These layers are said to be retinotopically mapped, which means that adjacent neurons will receive information about adjacent regions in the visual field. Each of these cells has a round concentric receptive field – like the ganglion cells.

From the LGN, information travels, via the optic radiation, to the primary visual cortex (V1), sometimes also referred to as the striate cortex because of its striped appearance. The cortex consists of a series of layers. The upper layer is labelled Layer I and the deepest or innermost layer is layer VI. Information from the LGN enters the primary visual cortex in layer IV (Figure 3.2).

There will be many thousands of cortical neurons receiving information from each small region of the retina and these cells are organized into columns which respond to specific stimulus features such as orientation. This means that cells in one orientation column preferentially respond to a specific orientation (e.g. lines at 45° clockwise from the vertical) whilst those in the next column will respond to a slightly different orientation. Across all columns, all orientations can be represented. Primary visual cortex can also be divided into columns that respond preferentially to one eye or the other – these are termed ‘ocular dominance columns’. Theoretically, the cortex can be split into ‘hypercolumns’ each of which contains representations from both ocular dominance columns and all orientations for each part of the visual field, though these do not map as neatly onto the cortical surface as was once theorised (Bartfeld and Grinvald, 1992).

However, despite the exquisite organization of the primary visual cortex, information does not stop at this point. In fact visual information travels to many different cortical regions – with 30 identified so far.