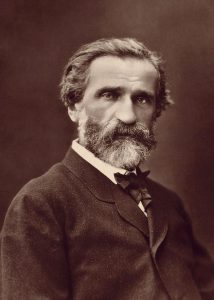

15. Music of Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) succeeded Giacomo Rossini as the most important Italian opera composer of his day. Living during a time of national revolution, Verdi’s music and name become associated with those fighting for an Italy that would be united under King Emmanuel. A chorus from one of his early operas about the ancient enslaved Hebrews would become a political song for Italian independent fighters. His last name, V.E.R.D.I. would become an acronym for a political call to rally around King Emmanuel. Although Verdi shied away from the political limelight, he was persuaded to accept a post in the Italian parliament in 1861.

As was the case with many sons of 19th-century middle-class families, Verdi was given many and early opportunities to further his education. He began music instruction with local priests before his fourth birthday. Before he turned ten, he had become organist of the local church, and he continued music lessons alongside lessons in languages and the humanities through his adolescence. He assumed posts as music director and then in 1839 composed his first opera. Verdi would prove to be a prolific composer, writing 26 operas in addition to other large-scale choral works. His recitatives and arias in the operas were now arranged in the elaborate scena ad aria format, with the aria that contained both slower cantabile (more lyrical and song-like) and faster cabaletta (more animated). Verdi was also more flexible in his use of recitatives and arias and employed a much larger orchestras than previous Italian opera composers, resulting in operas that were as dramatic as they were musical. His operas span a variety of subjects, from always popular mythology and ancient history to works set in his present that participated in a wider artistic movement called verismo (realism).

Focus Composition: “Follie” and “Sempre libera” from La Traviata

A good example of Verdi’s operatic realism can be found in La Traviata (The Fallen Woman, 1853). This opera was based on a play by Alexandre Dumas. Verdi wanted it to be set in the present, but the censors at La Fenice, the opera house in Venice that would premiere the opera, insisted on setting it in the 1700s instead. Of issue was the heroine, Violetta—a companion-prostitute for the elite aristocrats of Parisian society—with whom Alfredo, a young noble, falls in love. After wavering over giving up her independence, Violetta commits herself to Alfredo, and they live a blissful few months together before Alfredo’s father arrives and convinces Violetta that she is destroying their family and the marriage prospects of Alfredo’s younger sister. In response, Violetta leaves Alfredo without telling him why and goes back to her old life. Alfredo is angry and hurt and the two live unhappily apart. A consumptive, that is, one suffering from tuberculosis, Violetta declines and her health disintegrates. Alfredo’s father has a crisis of conscience and confesses to his son what he has done. Alfredo rushes to Paris to reunite with Violetta. The two sing a love duet, but it is soon clear that Violetta is very ill, and she dies in Alfredo’s arms, before they can go to the church to be married. In ending tragically, this opera ends like many other 19th-century tales.

Verdi wrote this opera mid-century with full knowledge of the Italian operas before him. Like his contemporary, Richard Wagner, Verdi wanted opera to be a strong bond of music and drama. He carefully observed how German opera composers such as Carl Maria von Weber and French Grand Opera composers such as Giacomo Meyerbeer had used much larger orchestras than had previous opera composers, and Verdi himself also employed a comparably large ensemble for La Traviata. Verdi also believe in flexibly using the operatic forms he had inherited, and so although La Traviata does have recitatives and arias, the recitatives are more varied and lyrical than before and the alternation between the recitatives, arias, and other ensembles, are guided by the drama, instead of the drama having to fit within the structure of recitative-aria pairs. A good example is “La follie…Sempre libera” from the end of Act I, in which Violetta debates whether she is ready to give up her independence for Alfredo. Although at the end of the aria it seems that she has decided to remain free, Act II begins with the two lovers living happily together, and we know that the vocal injections sung by Alfredo as part of Violetta’s recitative and aria of Act I have prevailed. This piece is also a good example of how virtuoso opera had gotten by the end of the 19th century. Earlier Italian operas had been virtuoso in their use of ornamentation. Verdi, however, required a much wider range of his singers, and this wider range is showcased in the scene we are to watch. Violetta has a huge vocal range and performers must have great agility to sing the melisma in her part. As an audience, we are awed by her vocal prowess, a fitting response, given her character in the opera.

Listening Guide

Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro La Fenice, conducted by Carlo Rizzi; soprano Edita Gruberova as Violetta; tenor Neil Shicoff as Alfredo

Composer: Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Composition: “Follie” and “Sempre libera” from La Traviata

Date: 1853

Genre: recitatives and aria from an opera

Form: alternation between accompanied recitative and aria, with some repetition of sections

Nature of Text: libretto by Francesco Maria Piave; see the English translation.

Performing Forces: soprano (Violetta), tenor (Alfredo), and orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The virtuoso nature of Violetta’s singing

- The subtle shifts between recitative and aria, now less pronounced than in earlier operas

- A large orchestra that stays in the background

Other things to listen for: Alfredo’s more lyrical melody in distinction to Violetta’s virtuosity

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

| 0:08 | Violetta sings a very melismatic and wide-ranged melody with flexible rhythm. The orchestra provides sparse accompaniment. | Accompanied recitative: Follie! follie! Delirio vano è questo! Povera donna, sola, abbandonata in questo popoloso deserto che appellano Parigi. Che spero or più? Che far degg’io? Gioire, di voluttà ne’ vortici perir. |

| 0:52 | Violetta sings wide leaps, long melismas, and high pitches to emphasize the words. | Accompanied recitative: Gioir! (Pleasure!) |

| 1:04 | Stronger orchestral accompaniment as Violetta sings a more tuneful melody in a lilting meter with a triple feel | Aria: Sempre libera degg’io folleggiare di gioia in gioia, vo’ che scorra il viver mio pei sentieri del piacer. Nasca il giorno, o il giorno muoia, sempre lieta ne’ ritrovi, a diletti sempre nuovi dee volare il mio pensier. |

| 2:02 | Alfredo sings a more legato and lyrical melody in a high tenor range (this melody comes from earlier in the opera). | Alfredo’s melody: Amore, amor è palpito… dell’universo intero— Misterioso, misterioso, altero, croce, croce e delizia, croce e delizia, delizia al cor. |

| 2:38 | Violetta sings her virtuoso recitative and then transitions into her aria. | Accompanied recitative and aria: Follie… Sempre libera… |

| 3:52 | Alfredo sings his lyrical melody and Violetta responds after each phrase with a fast and virtuosic melisma. | Alfredo and Violetta: Repetition of text above |

Multiple pitches sung to one syllable of text.