3. Worship Music

During the Renaissance from 1442 to 1483, church choir membership increased dramatically in size. The incorporation of entire male ensembles and choirs singing in parts during the Renaissance is one major difference from the Middle Ages’ polyphonic church music, which was usually sung by soloists. As the Renaissance progressed, the church remained an important supporter of music, although musical activities gradually shifted to secular support. Royalty and the wealthy of the courts seeking after and competing for the finest composers replaced what was originally supported by the church. The motet and the mass are the two main forms of sacred choral music of the Renaissance.

3.1 Motet

The motet, a sacred Latin text polyphonic choral work, is not taken from the ordinary of the mass. A contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci and Christopher Columbus, Josquin des Prez (c. 1450-1521) was a master of Renaissance choral music. Originally from the region that is today’s Belgium, Josquin spent much of his time serving in chapels throughout Italy and partly in Rome for the papal choir. Later, he worked for Louis XII of France and held several church music directorships in his native land. During his career, he published masses, motets, and secular vocal pieces, and was highly respected by his contemporaries.

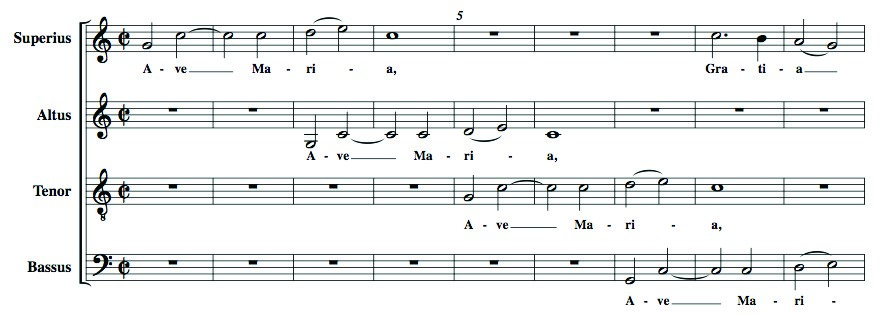

Focus Composition: “Ava Maria . . . Virgo Serena”(“Hail, Mary . . . Serene Virgin”) by Josquin des Prez

Josquin’s “Ava Maria . . . Virgo Serena” is an outstanding Renaissance choral work. A four part (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) Latin prayer, the piece weaves one, two, three, and four voices at different times in polyphonic texture.

Listening Guide

La Chapelle Royale, conducted by Philippe Herreweghe

To view a full score with text while listening, see the transcription by Dan Foster, Aoede Consort, Troy, New York.

Composer: Josquin des Prez (c. 1450-1521)

Composition: “Ava Maria . . . Virgo Serena”

Date: c. 1485, possibly Josquin’s earliest dated work

Genre: choral, motet

Form: through-composed in sections

Translation: available from John Mindeman

Performing Forces: four-part choir

What we want you to remember about this composition: The piece is revolutionary in how it presented the imitative weaving of melodic lines in polyphony. Each voice imitates or echoes the high voice (soprano).

Other things to listen for: After the initial introduction to Mary, each verse serves as a tribute to the major events of Mary’s life—her conception, the nativity, annunciation, purification, and assumption. See above translation.

3.2 Music of Catholicism: Renaissance Mass

In the 16th century, Italian composers excelled with works comparable to the mastery of Josquin des Prez and his other contemporaries. One of the most important Italian Renaissance composers was Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525–1594). Devoting his career to the music of the Catholic Church, Palestrina served as music director at St. Peter’s Cathedral, composed 450 sacred works and 104 masses. His influence in music history is best understood with a brief background of the Counter-Reformation.

Protestant reformists like Martin Luther and others, sought to correct malpractices and abuses within the structure of the Catholic Church. The Reformation began with Martin Luther and spread to two more main branches: The Calvinist and The Church of England. The protestant reformists challenged many practices that benefitted only the church itself and did not appear to serve the lay members (parishioners). A movement occurred within the church to counter the protestant reformation and preserve the original Catholic Church. The preservation movement or “Counter-Reformation” against the protestant reform led to the development of the Jesuit order (1540) and the later assembling of the Council of Trent (1545–1563) which considered issues of the church’s authority and organizational structure. The Council of Trent also demanded simplicity in music in order that the words might be heard clearly.

The Council of Trent discussed and studied the many issues facing the Catholic Church, including the church’s music. The papal leadership felt that the music had gotten so embellished and artistic that it had lost its purity and original meaning. It was neither easily sung nor was its words (still in Latin) understood. Many accused the types of music in the church as being theatrical and more entertaining rather than a way of worship (something that is still debated in many churches today). The Council of Trent felt melodies were secular, too ornamental, and even took dance music as their origin. The advanced weaving of polyphonic lines could not be understood, thereby detracting from their original intent of worship with sacred text. The Council of Trent wanted a paradigm shift of religious sacred music back toward monophonic Gregorian chant. The Council of Trent finally decreed that church music should be composed to inspire religious contemplation and not just give empty pleasure to the ear of the worshipper.

Focus Composition: Kyrie from Missa Papae Marcelli (Pope Marcellus Mass) by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Renaissance composer Palestrina heeded the recommendations from The Council of Trent and composed one of the period’s most famous works, Missa Papae Marcelli (Pope Marcellus Mass). Palestrina’s restraint and serenity reflect the recommendations of The Council of Trent. The text, though set to polyphonic melodies, is easily understood. The movement of the voices does not distract from the sacred meaning of the text. Through history, Palestrina’s works have been the standard for their calmness and quality.

Listening Guide

The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers

Follow the musical score (full page version or in this video) as you listen to the composition.

Composer: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594)

Composition: Kyrie from Missa Papae Marcelli (Pope Marcellus Mass)

Date: c. 1562

Genre: choral, kyrie of mass

Form: through-composed (without repetition in the form of verses, stanzas, or strophes) in sections

Nature of Text: in Latin

Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison

(Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy, Lord have mercy)

Performing Forces: unknown vocal ensemble

What we want you to remember about this composition: Listen to the polyphony and how the voices move predominantly stepwise after a leap upward. After initial voice begins the piece, the other voices enter imitating the initial melody and then continue to weave the voices as more enter. Palestrina’s mass would come to represent proper counterpoint/polyphony and become the standard for years to come.

Other things to listen for: Even though the voices overlap in polyphony, the text is not lost in the intricate musical texture. The significance of the text is brought out and can be easily understood.

3.3 Music of the Protestant Reformation

As a result of the Reformation, congregations began singing strophic hymns in German with stepwise melodies during their worship services. This practice enabled full participation of worshipers. Full participation of the congregations’ members further empowered the individual church participant, thus contributing to the Renaissance’s Humanist movement. Early Protestant hymns stripped away contrapuntal textures, utilized regular beat patterns, and set biblical texts in German.

Focus Composition: “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”) by Martin Luther

Instead of a worship service being led with a limited number of clerics at the front of the church, Luther wanted the congregation to actively and fully participate, including in the singing of the service. Since these hymns were in German, members of the parish could sing and understand them. Martin Luther, himself a composer, composed many hymns and chorales to be sung by the congregation during worship, many of which Johann Sebastian Bach would make the melodic themes of his Chorale Preludes, 125 years after the original hymns were written. These hymns are strophic (repeated verses as in poetry) with repeated melodies for the different verses. Many of these chorales utilize syncopated rhythms to clarify the text and its flow (rhythms). Luther’s hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” is a good example of this practice. The chorales/hymns were usually in four parts and moved with homophonic texture (all parts changing notes in the same rhythm). The melodies of these hymn/chorales used as the basis for many chorale preludes performed on organs prior to and after worship services are still used today. Here is a version of a chorale prelude based on “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” by John Cavicchio.

Listening Guide

Composer: Martin Luther (1483-1546)

Composition: “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”, also known as the “Battle Hymn of the Reformation”)

Date: 1529

Genre: choral, hymn, four-part chorale

This piece was written to be sung by the lay church membership instead of just by the church leaders a was practiced prior to the Reformation.

Form: strophic

Nature of Text: in German

Translated to English by Frederic H. Hedge in 1853

A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing;

Our helper He, amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing:

For still our ancient foe doth seek to work us woe;

His craft and power are great, and, armed with cruel hate,

On earth is not his equal.

Did we in our own strength confide, our striving would be losing;

Were not the right Man on our side, the Man of God’s own choosing:

Dost ask who that may be? Christ Jesus, it is He;

Lord Sabaoth, His Name, from age to age the same,

And He must win the battle.

And though this world, with devils filled, should threaten to undo us,

We will not fear, for God hath willed His truth to triumph through us:

The Prince of Darkness grim, we tremble not for him;

His rage we can endure, for lo, his doom is sure,

One little word shall fell him.

That word above all earthly powers, no thanks to them, abideth;

The Spirit and the gifts are ours through Him Who with us sideth:

Let goods and kindred go, this mortal life also;

The body they may kill: God’s truth abideth still,

His kingdom is forever.

Performing Forces: whole congregation

Things to listen for: stepwise melody; syncopated rhythms centered around text

More on Martin Luther, watch this PBS documentary.

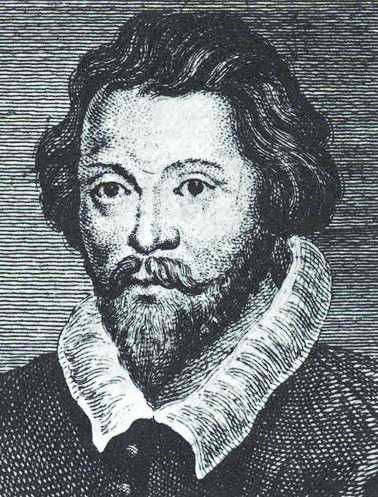

3.4 Anthem

English Composer William Byrd (1543–1623) became very distinguished from many of his contemporary composers because of his utilization of many different compositional tools that he used in his music. His works represent several musical personalities instead of one single style. As his career progressed, Byrd become more interested and involved in Catholicism. The influence of Catholicism through the use of biblical text and religious styles increasingly permeated his music. The mandates established and requirements imposed by the Council of Trent placed a serious stumbling block in the path of the development of church music compositional techniques after the reformation. Several denominations had to adapt to the mandates required by the Council of Trent. The music in the Catholic Church experienced relatively little change as the result of the reformation. This lack of change was due to composers like Byrd who remained loyal to the religion and their refusal to change their “traditional catholic” style of composing.

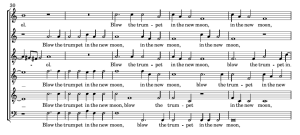

Focus Composition: “Sing Joyfully Unto God” by William Byrd

In Byrd’s Anglican Anthem, “Sing Joyfully Unto God,” the opening phrase of the text is set with a single voice on each part. This technique is very similar to the Catholic Church settings of Chant incipits. This full anthem (sung by the entire choir) by Byrd is much more polyphonic in nature than that of verse anthems (which incorporate solo passages and sections). It also borrows heavily from both madrigal and motet styles, though modified for the liturgy. “Sing Joyfully Unto God” is one of the most thoroughly motet-like anthems that Byrd composed. Within the anthem there is a new point of imitation for each new phrase of text. Byrd extensively uses the text depictions to creatively illustrate the music’s meaning. Below is an example of how Byrd’s “Sing Joyfully, Unto God” emphasizes the trumpet call of the text. All voices are singing together to depict the fullness of a trumpet fanfare, thickening the texture to illustrate the musical concept. This section begins with homophony and Byrd uses this technique primarily as a structural contrast device.

The use of imitation as a structural tool is maintained mainly within full anthems. Byrd also uses a technique called pairing of voices, which was highly popular within the Renaissance period.[1]

Listening Guide

University of Wisconsin Eau Claire Concert Choir

Composer: William Byrd (1543–1623)

Composition: “Sing Joyfully Unto God”

Date: c. 1580–1590

Genre: choral, church anthem

Form: through-composed

Nature of Text: in English

Sing joyfully to God our strength;

sing loud unto the God of Jacob!

Take the song, bring forth the timbrel,

the pleasant harp, and the viol.

Blow the trumpet in the New Moon,

even in the time appointed,

and at our feast day.

For this is a statute for Israel,

and a law of the God of Jacob.

Performing Forces: six-part choir, SSAATB

What we want you to remember about this composition: This is very much a motet-like church anthem. It sounds like a piece in a mass but the text does not come from any of the five sections of the mass. The work incorporates many of the polyphonic techniques used in the mass.

Significant points:

- one of the most popular pieces from the time period

- imitative polyphony

- scored in SSAATB (two soprano parts, two also parts, one tenor part, and one bass part, sung in a cappella

- text (Psalm 81)in English

- some word painting

- Mitchell, Shelley. “William Byrd: Covert Catholic Values with Anglican Anthems Comparison of Style to Catholic Gradualia.” MA thesis. Indiana State University, 2008. Web. 15 December 2015. ↵

A highly varied sacred choral musical composition. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music.

Catholic celebration of the Eucharist consisting of liturgical texts set to music by composers starting in the Middle Ages.