6. Music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

6.1 About Johann Sebastian Bach

During the 17th century, many families passed their trades down to the next generation so that future generations may continue to succeed in a vocation. This practice also held true for Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach was born into one of the largest musical families in Eisenach of the central Germany region known as Thuringia. He was orphaned at the young age of ten and raised by an older brother in Ohrdruf, Germany. Bach’s older brother was a church organist who prepared the young Johann for the family vocation. The Bach family, though great in number, were mostly of the lower musical stature of town’s musicians and/or Lutheran Church organists. Only a few of the Bachs had achieved the accomplished stature of court musicians, but the Bach family members were known and respected in the region. Bach also in turn taught four of his sons who later became notable composers for the next generation.

Bach received his first professional position at the age of eighteen in Arnstadt, Germany, as a church organist. This appointment was not a good philosophical match for the young aspiring musician. He felt his musical creativity and growth was being hindered and his innovation and originality unappreciated. The congregation seemed sometimes confused and felt the melody lost in Bach’s writings. He met and married his first wife, Maria Barbara (possibly his cousin), in 1707 while in Arnstadt. They had seven children together and two of their sons, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel became notable composers. Bach later was offered and accepted another position in Mühlhausen.

He continued to receive job offers, which he accepted, allowing him to advance in his career and attain a position at the court of Weimer, where he served for nine years (1708-1717). This position had a great number of responsibilities. Bach was required to write church music for the ducal church (the church for the duke who hired Bach), to perform as church organist, and to write organ music and sacred choral pieces for choir, in addition to writing sonatas and concertos (instrumental music) for court event performances. While at this post, Bach’s fame as an organist and the popularity of his organ works grew significantly.

Bach soon wanted to leave for another court musician position and his request to be released was not received well. This difficulty attests to the work relations of court musicians and their employers. Dukes expected and demanded loyalty from their court musician employees. Because musicians were looked upon somewhat as court property, the duke of the court often felt betrayed when a court musician wanted to leave. Upon hearing of Bach’s desire to leave and work for the prince of Cöthen, the Duke at Weimer refused to accept Bach’s resignation and threw Bach into jail for almost a month for submitting his dismissal request before relenting and letting Bach go to the Cöthen court.

The Prince of Cöthen was very interested in instrumental music. The Prince was a developing amateur musician who did not appreciate the elaborate church music of Bach’s past; instead, the Prince desired instrumental court music, so Bach focused on composing instrumental music. In his tenure at Cöthen (1717-1723), Bach produced an abundance of music for keyboard instruments, six concerti grossi honoring the Margrave of Brandenburg, suites, concertos, and sonatas. Bach’s wife Maria Barbara died In 1720. He later married a young singer, Anna Magdalena and they had thirteen children together. Half of these children did not survive infancy. Two of Bach’s sons birthed by Anna, Johann Christoph and Johann Christian, went on to become notable composers of the next generation.

At the age of thirty-eight, Bach assumed the position as cantor of the St. Thomas Lutheran Church in Leipzig, Germany. Several other candidates were considered for the Leipzig post, including the famous composer Georg Philipp Telemann who rejected the offer. Some on the town council felt that, since the most qualified candidates did not accept the offer, a less talented applicant would have to be hired. It was in this negative working atmosphere that Leipzig hired its greatest cantor and musician. Bach worked in Leipzig for twenty-seven years (1723–1750).

Leipzig served as a hub of Lutheran church music for Germany. Not only did Bach have to compose and perform, he also had to administer and organize music for all the churches in Leipzig. He was required to teach in choir school in addition to all of his other responsibilities. Bach composed, copied needed parts, directed, rehearsed, and performed a cantata on a near weekly basis. Cantatas are major church choir works that involve soloists, choir, and orchestra. Cantatas have several movements and last for fifteen to thirty minutes and are still performed today by church choirs, mostly on special occasions such as Easter, Christmas, and other festive church events.

Bach felt that the rigors of his Leipzig position were too bureaucratic and restrictive due to town and church politics. Neither the town nor the church really ever appreciated Bach. The church and town council refused to pay Bach for all the extra demands/responsibilities of his position and thought basically that they would merely tolerate their irate cantor, even though Bach was the best organist in Germany. Several of Bach’s contemporary church musicians felt his music (the style or types) was not considered current, a feeling which may have resulted from professional jealousy. One contemporary critic felt Bach was “old fashioned.”

Beyond this professional life, Bach had a personal life centered on his large family. He had seven children by his first wife, one by a cousin, and thirteen by his second wife, Anna Magdalena. He wrote a little home school music curriculum entitled The Notebook of Anna Magdalena Bach. At home, the children were taught the fundamentals of music, music copying, performance skills, and other musical content. Bach’s children utilized their learned music copying skills in writing the parts from the required weekly cantatas that their father was required to compose. Bach’s deep spirituality is evident and felt in the meticulous attention to detail of his scared works, such as his cantatas, passions, and masses, that are unequaled by other composers.

Bach did not travel much, with the exception of being hired as a consultant with construction contracts to install organs in churches. He would be asked to test the organs and to be part of their inauguration ceremony and festivities. The fee for such a service ranged from a cord of wood to possibly a barrel of wine. In 1747, Bach went on one of these professional expeditions to the court of Frederick the Great of Prussia in Potsdam, an expedition that proved most memorable. Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, served as the accompanist for the monarch of the court who played the flute. Upon Bach’s arrival, the monarch showed him a new collection of fortepianos (the early pianos that were now beginning to replace harpsichords in homes of society). The King then presented Bach with a complex musical theme, challenging him to improvise a three-voice fugue on it. Bach successfully improvised the fugue, impressing Frederick and the court. However, Frederick further challenged Bach to improvise a six-voice fugue on the same theme. Recognizing the difficulty, Bach requested time to compose it properly. Upon returning to Leipzig, Bach composed a collection of pieces based on Frederick‘s theme, entitled The Musical Offering. The title attested to his highest respect for the monarch and stated that the King should be revered.

Bach later became blind but continued composing through dictating to his musician children. He had also already begun to organize his compositions into orderly sets of organ chorale preludes, harpsichord preludes and fugues, and organ fugues. He started to outline and recapitulate his conclusive thoughts about Baroque music, forms, performance, composition, fugal techniques, and genres. This knowledge and innovation appears in such works as The Art of Fugue—a collection of fugues all utilizing the same subject that was left incomplete due to his death—the thirty-three Goldberg Variations for Harpsichord, and the Mass in B minor.

Bach was an intrinsically motivated composer who also composed music for himself, a small group of students, and close friends. This type of compositions was a break from the previous norms of composers. Bach’s music was largely overlooked and undervalued by the public following his death. However, it gained appreciation and respect from important composers later on, such as Mozart and Beethoven.

Over the course of his lifetime, Bach created a significant number of works, including The Well-Tempered Clavier (forty-eight preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys), three sets of harpsichord suites (six movements in each set), the Goldberg Variations, many organ fugues and chorale preludes (which are organ solos based upon church hymns—several by Martin Luther), the Brandenburg Concertos, composite works such as A Musical Offering and The Art of Fugue, an excess of 200 secular and sacred cantatas, two Passions from the gospels of St. Matthew and St. John, Christmas Oratorio, Mass in B minor, several chorale/hymn harmonizations, concertos, orchestral suites, and sonatas.

Focus Composition: Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is Our God), Cantata BWV 80

Bach’s A Mighty Fortress is Our God cantata, like most of his cantatas, has several movements. It opens with a polyphonic chorus that presents the first verse of the hymn. After several other movements (including recitatives, arias, and duets), the cantata closes with the final verse of the hymn arranged for four parts. For a comparison of cantata, opera, and oratorio, see the chart earlier in this chapter.

Bach composed some of this music when he was still in Weimar (BWV 80A) and then he revised and expanded the cantata for performance in Leipzig around 1730 (BWV 80B), with additional re-workings between 1735 and 1740 (BWV 80).

Listening Guide

Netherlands Bach Society; Shunske Sato, violin and direction; Isabel Schicketanz, soprano; Franz Vitzthum, alto; Thomas Hobbs, tenor; Wolf Matthias Friedrich, bass

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Composition: Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is Our God), Cantata BWV 80

Date: 1715-1740

Genre: choral with orchestral accompaniment; sacred

0:00 Movement 1: chorus, SATB

5:23 Movement 2: aria

8:52 Movement 3: recitative

10:54 Movement 4: aria

14:02 Movement 5: chorale

17:10 Movement 6: recitative

18:34 Movement 7: aria

22:31 Movement 8: chorale, SATB

Form:

The first movement is a polyphonic setting of Martin Luther’s chorale melody.

The final movement is set to the last stanza (verse) of Martin Luther’s hymn, in chorale style.

Nature of Text: in German; for English translation, see here.

Performing Forces: choir and orchestra (vocal soloists appear in movements 2-7.)

What we want you to remember about this composition: This is representative of Bach’s mastery of using a Martin Luther hymn as the initial melodic idea to create a composition of imitative polyphony and more, for all four vocal parts and the orchestra.

Other things to listen for:

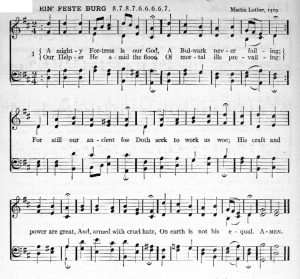

- How Bach changes the original melody (which can be heard in the final movement; Figure 4.13 shows a music notation from a hymn book that has the top melody very close to the soprano line of the chorale in this Cantata) and makes his new melodies, weaving them into a beautiful polyphonic choral work as the first movement

- Outlines of Bach’s melodies that are still similar to Luther’s original melody; modified rhythmic structures (rhythmic augmentation or diminution)

- Instruments doubling (playing the same music as) the vocal parts

Figure 4.13 | Notation of “A Mighty Fortress,” by Drboisclair, via Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

6.2 The Baroque Keyboard Instruments

Bach was born into a century that saw great advancements in keyboard instruments and keyboard music. The primary keyboard instruments used during the Baroque period included harpsichord, clavichord, and organ. The harpsichord is a keyboard instrument whose strings are put into motion by pressing a key that facilitates a plucking of a string by quills of feathers (instead of being struck by hammers like the piano). The tone produced on the harpsichord is bright but cannot be sustained without re-striking the key. Dynamics are very limited on the harpsichord. In order for the tone to continue on the harpsichord, keys are replayed, trills are utilized, embellishments are added, and chords are broken into arpeggios. Harpsichords are used a great deal for counterpoint in the middle voices.

During the early Baroque era, the clavichord remained the instrument of choice for the home; indeed, it is said that Bach preferred it to the harpsichord. It produced its tone by a means of keys attached to metal blades that strike the strings. As we will see in the next chapter, by the end of the 1700s, the piano would replace the harpsichord and clavichord as the instrument of choice for residences.

Bach was best known as a virtuoso organist, and he had the opportunity to play on some of the most advanced pipe organs of his day. Sound is produced on the organ with the depression of one or more of the keys which activates a mechanism that opens pipes of a certain length and pitch through which wind from a wind chest rushes. The length and material of the pipe determines the tones produced. Levers called stops provide further options for different timbres. The Baroque pipe organ operated on relatively low air pressure as compared to today’s organs, resulting in a relatively thin transparent tone and volume. Most Baroque organs had at least two keyboards, called manuals (after the Latin word for hand), and a pedal board, played by the two feet. The presence of multiple keyboards and a pedal board made the organ an ideal instrument for polyphony. Each of the keyboards and the pedal board could be assigned different stops and thus could produce different timbres and even dynamic levels, which helped define voices of the polyphonic texture. Bach composed many of his chorale preludes and fugues for the organ.

6.3 The Fugue

The fugue is one of the most spectacular and magnificent achievements of the Baroque period. During this era of fine arts innovation, scientific research, natural laws, and systematic approaches to imitative polyphony were further developed and standardized. Polyphony first emerged in the late Middle Ages. Independent melodic lines overlapped and were woven. In the Renaissance, the polyphony was further developed by a greater weaving of the independent melodic lines. The Baroque composers, under the influence of science, further organized it into a system. The term fugue comes from the Latin word fuga, which means “to run away or take flight.” The fugue is a contrapuntal (polyphonic) piece for a set number of musicians, usually three of four. The musical theme of a fugue is called the subject.

You may think of a fugue as a gossip party. The subject (of gossip) is introduced in one corner of the room between two people. Another person in the room then begins repeating the gossip while the original conversation continues. Then another person picks up on the story and begins repeating the now third-hand news and it then continues a fourth time. A new observer walking into the room will hear bits and pieces from four conversations at one time—each repeating the original subject (gossip).

Fugues begin with an exposition. This is when the subject is introduced until the original subject has been sung or played in all the voices or parts. Most fugues are in the four standard voices/parts. In an instrumental work of fugue, we refer to the parts using voices—soprano, alto, tenor, and bass—to indicate the ranges of notes. At the beginning of a fugue, any of the four voices can be the first to start with the subject. Then another voice starts with the subject at a time dictated in the music while the first voice continues to more material. The imitation is continued through all the voices, as illustrated below (this example starts with the highest voice to the lowest voice in order). The exposition of the fugue is over when all the voices complete the initial subject.

Voice 1 Soprano: Subject—continues in a counter subject

Voice 2 Alto: Subject—continues in a counter subject

Voice 3 Tenor: Subject—continues in a counter subject

Voice 4 Bass: Subject—continues in a counter subject

After the exposition is completed, it may be repeated in a different order of voices or it may continue with less weighted entrances at varying lengths known as episodes. This variation provides a little relaxation or relief from the early regiment systematic polyphony of the exposition. In longer fugues, the episodes are followed by a section in another key with continued overlapping of the subject. This process can continue to repeat until they return to the original key.

Fugues are sometimes performed as a prelude to traditional worship on the pipe organ and are quite challenging to perform by the organist. Hands, fingers, and feet must all be controlled independently by the organist and all at the same time. Often in non-fugal music, this type of polyphony is briefly written into a piece of music as an insert, called a fugato or fugato section. When voices overlap in a fugue, it is called stretto (similar to strata). When the first voice continues after the second voice enters, the music of the first voice is then called the countersubject. The development of musical themes or subjects by lengthening or multiplying the durations of the notes or pitches is called augmentation. The shortening or dividing the note and pitch durations is called diminution. Both augmentation and diminution are utilized in the development of the musical subjects in fugues and in thematic development in other genres. The “turning up-side down” of a musical line is called inversion.

Focus Composition: “Little” Fugue in G Minor, BWV 578

Bach’s “Little” Fugue in G Minor, BWV 578, is called “Little” to distinguish it from another of Bach’s works, the “Great” Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor, BWV 542. The “Great” Fugue is longer and more complex, whereas the “Little” Fugue is shorter in duration.

Listening Guide

Ton Koopman, organ

Robert Köbler, organ; audio recording with music score in the video

The analysis below is following the timing of this recording.

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Composition: Organ Fugue in G Minor, BWV 578

Date: c. 1709

Genre: instrumental, solo organ

Form: fugue

Nature of Text: instrumental music, no text

Bach was able to take the earlier vocal polyphony of the Renaissance period and apply it to a fugue written for the organ. This is regarded as one of Bach’s great achievements.

Performing Forces: solo organ

What we want you to remember about this composition: how Bach weaves and overlaps the subject throughout the piece.

Other things to listen for:

- The subject is introduced in the highest voices and then is imitated in each lower voice in order: soprano, alto, tenor and then bass in the pedals. After the exposition is completed in the bass pedals, the subject is introduced in the first voice again. Upon the entrance of the second layer, the first voice goes into a countersubject. Just before the subject is introduced five more times, it is preceded by a brief episode. In each episode the subject is not played in its entirety.

- Even though the fugue is in G minor, the piece ends with a major chord, a common practice utilized during the Baroque period. Major chords were thought more conclusive than minor chords.

| Timing | Melody, Texture, and Form |

| 0:00 | Subject in soprano voice alone, minor key |

| 0:19 | Subject in alto, countersubject in shorter notes in soprano |

| 0:43 | Subject in tenor, countersubject above it; brief episode follows |

| 1:01 | Subject in bass (pedals), countersubject in tenor |

| 1:18 | Brief episode |

| 1:30 | Subject begins in tenor and continues in soprano. |

| 1:50 | Brief episode, shorter notes in a downward sequence |

| 1:59 | Subject in alto, major key; countersubject in soprano |

| 2:16 | Episode in major, upward leaps and shorter notes |

| 2:29 | Subject in bass (pedals), major key, countersubject and long trill above it |

| 2:44 | Longer episode |

| 3:04 | Subject in soprano, minor key, countersubject below it |

| 3:21 | Extended episode |

| 3:53 | Subject in bass (pedals), countersubject in soprano; composition ends with major chord. |

Perfected by J.S. Bach during the baroque period, fugues are a form written in an imitative contrapuntal style in multiple parts. Fugues are based upon their original tune that is called the subject. The subject is then imitated and overlapped by the other parts called the answer, countersubject, stretto, and episode.

A major composite church choral form of music from the Baroque period that involves soloist, choir, and orchestra. Cantatas have several movements and last for fifteen to thirty minutes. Cantatas are performed without staging but they utilize narration, arias, recitatives, choruses, and smaller vocal ensembles.