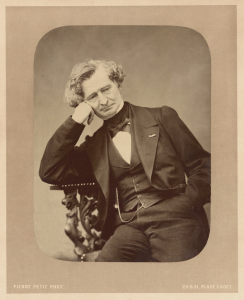

8. Music of Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) was born in France in La Côte-Saint-André, Isère near Grenoble. His father was a wealthy doctor and planned on Berlioz’s pursuing the profession of a physician. At the age of eighteen, he was sent to study medicine in Paris. Music at the Conservatory and at the Opera, however, became the focus of his attention. A year later, his family grew alarmed when they realized that the young man had decided to study music instead of medicine.

At this time, Paris was in a Romantic revolution. Berlioz found himself in the company of novelist Victor Hugo and painter Delacroix. No longer receiving financial support from his parents, the young Berlioz sang in the theater choruses, performed musical chores, and gave music lessons. As a young student, Berlioz was amazed and intrigued by the works of Beethoven. He also developed interest in Shakespeare, whose popularity in Paris had recently increased with the performance of his plays by a visiting British troupe. Berlioz became impassioned for the Shakespearean characters of Ophelia and Juliet as they were portrayed by the alluring actress Harriet

Smithson. He soon found himself infatuated with the young actress, and was deeply saddened by her lack of interest in him as a suitor. Berlioz became known for his violent mood swings, a condition known today as manic depression.

In 1830, Berlioz earned his first recognition for his musical gift when he won the much sought-after Prix de Rome. This highly esteemed award provided him with a stipend, allowing him to work and live in Paris, and he completed his most famous work, Symphonie fantastique, that year. The award also included a scholarship for Berlioz to study in Rome for two years.

Upon his return from Rome, Berlioz began his intense courtship of Harriet Smithson. Both her and his families vehemently opposed their relationship. Several violent and arduous situations occurred, one of which involved Berlioz’s unsuccessfully attempting suicide. After recovering from this attempt, he married Harriet. Once the previously unattainable matrimonial goal had been attained, Berlioz’s passion somewhat cooled, and he discovered that it was Harriet’s Shakespearean roles that she performed, rather than Harriet herself, that really intrigued him. The first year of their marriage was the most fruitful for him musically. By the time he was forty, he had composed most of his famous works. Bitter from giving up her acting career for marriage, Harriet became an alcoholic. The two separated in 1841. Berlioz then married his long time mistress Marie Recio, an attractive but average singer who demanded to perform in his concerts.

To supplement his income during his career, Berlioz turned to writing as a music critic, producing a steady stream of articles and reviews. He successfully utilized this vocation as a way to support his own works by persuading the audience to accept and appreciate them. His critical writing also helped to educate audiences so they could understand his complex and innovative pieces. As a prose writer, Berlioz wrote The Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. He also wrote ‘Les Soirées de l’Orchestre’ (Evenings with the Orchestra), a compilation of his articles on musical life in 19th-century France, and an autobiography entitled Mémoires. Later in life, he conducted his music in all the capitals of Europe, with the exception of Paris. It was one location where the public would not accept his work; the Paris public would read Berlioz’s reviews and learn to welcome lesser composers, but they would not accept his music. As over the years Berlioz saw his own works neglected by the public of Paris while they cheered and supported others, he became disgusted and bitter from the neglect. His last final work composed to gain acceptance by the Parisian audiences was the opera Béatrice et Bénédict with his own libretto based upon Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing. But the Parisian public did not appreciate it. After this final effort, the disillusioned and embittered Berlioz composed no more in his seven remaining years, dying rejected and tormented at the age of sixty-six. Only after his death would France appreciate his achievements.

His operas and large vocal works include Benvenuto Cellini, Le Troyens, Béatrice et Bénédict, Les francs-juges (incomplete), Grande Messe des morts (or Requiem), La damnation de Faust, Te Deum, L’enfance du Christ, and Roméo et Juliette. His major orchestral and instrumental compositions include Symphonie fantastique, Harold en Italie, Le corsaire, Le roi Lear, and Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale. Berlioz is credited for changing the modern sound of orchestras.

Focus Composition: First Movement, Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique is important for several reasons: it is a program symphony, it incorporates an idée fixe (a recurring theme representing an ideology or person that provides continuity through a musical work), and it contains five movements rather than the four of most symphonies.

Listening Guide

The BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Yan Pascal Tortelier

Composer: Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

Composition: “Rêveries – Passions,” first movement, Symphonie fantastique, Op.14

Date: 1830

Genre: symphony, first movement

Form: sonata form

Performing Forces: large Romantic symphony orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The largo (slow) opening is pensive and expressive, depicting the depression, the joy, and the fruitless passion Berlioz felt. It is followed by a long and very fast section with a great amount of expression, with the idée fixe indicating the appearance of his beloved.

- The title for the movement is “Dreams, Passions.” It represents his uneasy and uncertain state of mind. The mood quickly changes as his loved one appears to him. He reflects on the love inspired by her. He notes the power of his enraged jealousy for her and of his religious consolation at the end.

Other things to listen for: Berlioz is known for being one of the greatest orchestrators of all time. He even wrote the first comprehensive book on orchestration. He always thought in terms of the exact sound (tone or timbre) of the orchestra and the mixture of individual sounds to blend through orchestration. He gave very detailed instructions to the conductor and individual performers in regards to articulations and how he wanted them to play. Listen to the subtleties and nuance of the performance. Berlioz left little up to chance since he was so thorough in his compositions.

| Timing | Score Measure Numbers | Form, Melody, and Texture |

| 0:07 | 1-2 | Winds, triplets and a long note, very quietly |

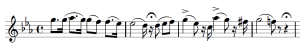

| 00:18 | 3–16 | The introductory four-bar phrase played by the first violins forms the basis for the following three phrases to measure 16, most of the music being played on muted strings. Here the composer portrays both depression and elation.

Measures 3-6 |

| 1:44 | 17–71 | The key changes from C minor to E♭ major and to C minor, finally arriving in C major with a cadence in measures 62-63. |

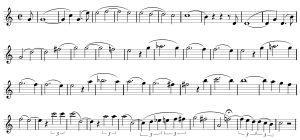

| 5:30 | 72–132 | Exposition-Allegro “He sees his beloved and is overcome with many different emotions.” First subject—idée fixe—played by the flute and first violins. The key of C major is established by the dominant pedal point.

Measures 72-111 |

| 6:32 | 133–149 | Transition section that provides rising tension in the approach to the dominant. |

| 6:48 | 150–167a | Second subject introduced and established in the key of G major at measure 160.

Measures 160-166 |

| 7:05 | 72-165 | Exposition repeated |

| 8:36 | 166–228 | Development—two motives from the previous sections are featured in this section. The first has become known as the “sigh motive,” which musically represents the sighing figure of a long note followed by a shorter note.

Measures 87-89 The second motive has become known as the “heart beat motive,” which is heard as a pair of detached quicker notes. These are brought out dynamically (volume emphasis) and represent heart beats. Measures 78-79 |

| 9:31 | 229-231 | Silence |

| 9:33 | 232–277 | Recapitulation in the dominant key of C major |

| 10:20 | 278–310 | Transitional passage to the upcoming second subject |

| 10:51 | 311–409 | Second subject resolving fortissimo in C major; development continued further; tension gradually increased, setting up for the next tutti section |

| 12:41 | 410–439 | The full orchestra plays the first subject in C major. |

| 13:08 | 440–474 | Further orchestral build-up |

| 13:43 | 475–525 | Coda—after the last peak of sequential and dynamic build-up, the music slows and quiets down until the final chords, which musically represent the consolation of religion ending with a plagal cadence (traditional Amen progression, subdominant chord followed by tonic chord). |

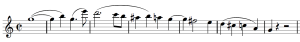

A melodic motive that appears in all five movements of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique to represent the beloved from the program.