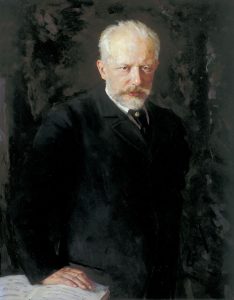

13. Music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Pyotr (Peter) Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was born in Votinsk, a small mining town in Russia. He was a son of a government official, and started learning piano at the age of five, though his family intended him to have a career as a government official. His mother died of cholera when he was fourteen, a tragedy that had a profound and lasting effect on him. He attended the aristocratic school in St. Petersburg called the School of Jurisprudence and, upon completion, obtained a minor government post in the Ministry of Justice. Nevertheless, he always had a strong interest in music and yearned to study it.

At the age of twenty-three, he resigned his government post and entered the newly founded St. Petersburg Conservatory to study music. He studied intently and completed his studies in three years. His primary teachers at the conservatory were Anton Rubinstein and Konstantin Zarembe, and he also taught lessons while he studied. When he finished his studies, Tchaikovsky was recommended by Rubinstein, then the director of the Conservatory of St. Petersburg, to a teaching post at the Moscow Conservatory. The young professor of harmony had full teaching responsibilities with long hours and a large class. Despite his heavy workload, his twelve years at the conservatory saw the composing of some of his most famous works, including his first symphony. At the age of twenty-nine, he completed his first opera Voyevoda and composed the Romeo and Juliet overture. At the age of thirty-three, he started supplementing his income by writing as a music critic, and also composed his second symphony, first piano concerto, and his first ballet music, Swan Lake.

The reception of his music sometimes included criticism, and Tchaikovsky took criticism very personally, being prone as he was to (attacks of) depression. These bouts with depression were exacerbated by an impaired personal social life. In an effort to calm and smooth that personal life, Tchaikovsky entered into a relationship and marriage with a conservatory student named Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova in 1877. She was star struck and had fallen immediately and rather despairingly in love with him. His pity for her soon turned into unmanageable dislike to the point that he avoided her at all cost. Once in a fit of depression and aversion, he even strolled into the icy waters of the Moscow River to avoid her. Many contemporaries believe the effort was a suicide attempt. A few days later, nearly approaching a complete mental breakdown, he sought refuge and solace fleeing to his brothers in St. Petersburg. The marriage lasted less than a month.

At this darkest hour for Tchaikovsky, a kind, widowed, and wealthy industrialist, Nadezhda von Meck became his sponsor. Madame von Meck, who loved Tchaikovsky’s music, was dominating and emotional. From her secluded estate, she raised her eleven children and managed her estate and railroads. Her financial support helped restore Tchaikovsky to health, freed him from his burdensome teaching responsibilities, and permitted him to focus on his compositions. Due to the social norms of the era, she had to be very careful to make sure that her intentions in supporting the composer went towards his music and not towards the composer as a man. Consequently, they never met one another other than possibly through the undirected mutual glances at a crowded concert hall or theater. They communicated through a series of letters to one another, and this distance letter-friendship soon became one of fervent attachment.

In his letters to Madame von Meck, Tchaikovsky would explain how he envisioned and wrote his music, describing it as a holistic compositional process, with his envisioning the thematic development to the instrumentation being all one thought. The secured environment she afforded Tchaikovsky enabled him to compose unrestrainedly and very creatively. In appreciation and respect for his patron, Tchaikovsky dedicated his fourth symphony to her, which he composed in his mid-thirties, the decade when he premiered his opera Eugene Onegin and composed the 1812 Overture and Serenade for Strings.

Tchaikovsky’s music ultimately earned him international acclaim, leading to his receiving a lifelong subsidy from the Tsar in 1885. He overcame his shyness and started conducting appearances in concert halls throughout Europe, making his music the first of any Russian composers to be accepted and appreciated by Western music consumers. At the age of fifty, he premiered The Sleeping Beauty and The Queen of Spades in St. Petersburg. A year later, in 1891, he was invited to the United States to participate in the opening ceremonies for Carnegie Hall. He also toured the United States, where he experienced impressive hospitality. He grew to admire the American spirit, feeling awed by New York’s skyline and Broadway. He wrote that he felt he was more appreciated in America than in Europe.

While his composition career sometimes left him feeling dry of musical ideas, Tchaikovsky’s musical output was astonishing and included, at this later stage of his life, his sixth symphony Pathétique, music for the ballet The Nutcracker, and the opera Iolanta, all of which received their premiere in St. Petersburg. He conducted the premier of his sixth symphony but was met with only a lukewarm reception, partially because of his shy, lackluster personality. The persona carried over into his conducting technique that was rather reserved and subdued, leading to a less than emotion-packed performance by his orchestra.

A few days after the premier of the sixth symphony, while he was still in the St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky ignored warnings against drinking unboiled water, which was given due to the current prevalence of cholera there. He contracted the disease and died within a week at the age of fifty-three. Immediately upon his tragic death, the Pathétique Symphony earned great acclaim that it has held ever since.

In the 19th century and still today, Tchaikovsky is among the most highly esteemed of composers. Russians have the highest regard for Tchaikovsky as a national artist. Igor Stravinsky, for example, is said to have called him “the most Russian” composer. Tchaikovsky incorporated the national emotional feelings and culture—from its simple countryside to its busy cities—into his music. Along with his nationalism influences, such as Russian folk song, Tchaikovsky enjoyed studying and incorporating German symphony, Italian opera, and French ballet. He was comfortable with all of these disparate sources and gave all his music lavish melodies flooding with emotion.

Tchaikovsky composed a tremendously wide spectrum of music, with ten operas including Eugene Onegin, The Maid of Orleans, Queen of Spades, and Iolanta; internationally acclaimed ballet music, including Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, Snow Maiden, and Hamlet; six symphonies, three piano concertos, various overtures, chamber music, piano solos, songs, and choral works.

Focus Composition: 1812 Overture

Listening Guide

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Adrian Leaper

Composer: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Composition: 1812 Overture

Date: composed in 1880

Genre: concert overture

Form: sectional and programmatic; musical sections defined by different thematic ideas

Performing Forces: large orchestra, including a percussion section with large bells and a battery of cannons

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- The piece depicts preparation for war, the actual conflict, and victory after the war is ended. It is quite descriptive in nature.

- Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture is one of the most famous and forceful pieces of classical music. It is particularly famous for its epic finale.

- The composition was made famous and mainstream to the public in the United States through public concerts on July 4th by city orchestras such as the Boston Pops. Though the piece was written to celebrate the anniversary of Russia’s victory over France in 1812, the piece’s finale is very often used for the 4th of July during fireworks displays.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

| 0:01 | The Russian hymn “Spasi, Gospodi, Iyudi Tvoya” (“O Lord, Save Thy People”) is performed in the strings. |

| 2:01 | The music morphs into a more suspenseful style creating tension of possible upcoming conflict. The tempo then picks up. |

| 3:43 | Snare drums set a military tone as a calling-horn theme is introduced. Listen to how the rhythms line up clear and precise. |

| 4:38 | An energetic disjunctive style portray an attack from the French. Brief motives of “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem are heard. The energy continues to build. The musical tension diminishes. |

| 6:36 | A lyrical and peaceful theme is introduced, contrasting the previous war scene. |

| 8:10 | A traditional folkdance tune “U vorot” (“At the gate”) from Russia is introduced into the work. |

| 8:50 | The energetic conflicting melodies return. |

| 10:27 | The lyrical tune returns. |

| 11:11 | The folkdance tune returns. |

| 11:30 | The “La Marseillaise” motive appears again in the horns. The tension and energy again build. |

| 12:06 | Percussion and even real cannons are used to depict the climax of the war conflict. This is followed by a musical loss of tension through descending and broadening lines in the strings. |

| 12:58 | The Russian Hymn is heard again in victory with the accompaniment of all the church bells in celebration commemorating victory throughout Russia. |

| 13:57 | The music excels, portraying a hasty French retreat (calling-horn theme). |

| 14:08 | The Russian anthem with cannons/percussion overpowers the French military theme, and the church bells join in again, symbolic of the Russian victory. |