16. Music of Richard Wagner (1813–1883)

If Verdi continued the long tradition of Italian opera, Richard Wagner (1813–1883) provided a new path for German opera. Wagner may well have been the most influential European composer of the second half of the 19th century. Never shy about self-promotion, Wagner himself clearly thought so. Wagner’s influence was both musical and literary. His dissonant and chromatic harmonic experiments even influenced the French, whose music belies their many verbal denouncements of Wagner and his music. His essays about music and autobiographical accounts of his musical experiences were widely followed by 19th-century individuals, from the average bourgeois music enthusiast to philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche. Most disturbingly, Wagner was rabidly antisemitic, and generations later his writing and music provided propaganda for the Nazi Third Reich.

Born in Leipzig, Germany, Wagner initially wanted to be a playwright like Goethe, until as a teenager he heard the music of Beethoven and decided to become a composer instead. He was particularly taken by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the addition of voices as performing forces into the symphony. Seeing in this work an acknowledgement of the powers of vocal music, Wagner set about writing vocal music. Coming to age during a time of rising nationalism, Wagner criticized Italian opera as consisting of cheap melodies and insipid orchestration unconnected to its dramatic purposes, and he set about providing a German alternative. He called his operas music dramas in order to emphasize a unity of text, music, and action; and declared that they would be Gesamtkunstwerk (total works of art). As part of his program, he wrote his own librettos and aimed for what he called unending melody: the idea was for a constant lyricism, carried as much by the orchestra as by the singers.

Perhaps most importantly, Wagner developed a system of what scholars have come to call Leitmotiv (leitmotif). Leitmotifs, or “guiding motives,” are musical motives that are associated with a specific character, theme, or locale in a drama. Wagner integrated these musical motives in the vocal lines and orchestration of his music dramas at many points. Wagner believed in the flexibility of such motives to reinforce an overall sense of unity within his compositions, even if primarily at a subconscious level. Thus, while a character might be singing a melody line using one leitmotif, the orchestration might incorporate a different leitmotif, suggesting a connection between the referenced entities.

Wagner also designed and built a theatre for the performance of his own music dramas. The Bayreuth Festival Theatre, Germany was the first to use a sunken orchestra pit, and its huge backstage area allowed for some of the most elaborate sets of Wagner’s day. It was here that his famous cycle of music dramas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelungen, also known as The Ring Cycle), was performed, starting in 1876. The Ring of the Nibelungen consists of four music dramas—Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung—with over fifteen hours of music. Wagner took the story from a Nordic mythological legend that stems back to the Middle Ages. In it, a piece of gold is stolen from the Rhine River and fashioned into a ring, which gives its bearer ultimate power. The cursed ring changes hands, causing destruction around whoever possesses it. Eventually the ring is returned to the Rhine River, thereby closing the cycle. Into that story, which some may recognize from the much later fiction Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, Wagner interwove stories of the Norse gods and men. Wagner’s four music dramas trace the saga of the king of the gods, Wotan, as he builds Valhalla, the home of the gods, and attempts to order the lives of his children, including that of his daughter, the Valkyrie warrior Brünnhilde.

Focus Composition: Conclusion to Die Walküre (The Valkyrie)

At the end of The Valkyrie, Brünnhilde has gone against her father, and, because Wotan cannot bring himself to kill her, he puts her to sleep before encircling her with flames, a fiery ring that both imprisons and protects his daughter. This excerpt provides several examples of the leitmotifs for which Wagner is so famous. Their presence, often subtle, is designed to guide the audience through the drama. They include melodies, harmonies, and textures that represent Wotan’s spear, the god Loge (a shape shifting life force that here takes the form of fire), sleep, the magic sword, and fate. The sounds of these motives are discussed briefly below and accompanied by excerpts from the musical score.

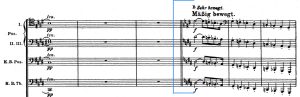

The first motive heard in the video you will watch is Wotan’s Spear. The spear represents Wotan’s power. In this scene, Wotan is pointing it toward his daughter Brünnhilde, ready to conjure the ring of fire that will both imprison and protect her. Representing a symbol of power, the spear motive is played at a forte dynamic by the lower brass. Here it descends in a minor scale that reinforces the seriousness of Wotan’s actions.

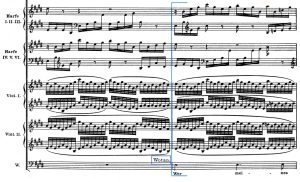

Wotan commands Loge to appear and suddenly the music breaks out in a completely different style. Loge’s music—sometimes also referred to as the magic fire music—is in a major key and appears in upper woodwinds such as the flutes. Its notes move quickly with staccato articulations suggesting Loge’s free spirit and shifting shapes.

Depicting Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep, Wagner wrote a chromatic musical line that starts high and slowly moves downward. We call this phrase the Sleep motive.

After casting his spell, Wotan warns anyone who is listening that whoever would dare to trespass the ring of fire will have to face his spear. As the drama unfolds in the next opera of the tetralogy, one character—Siegfried, Wotan’s own grandson—will do just that, releasing Brünnhilde using a magic sword. The melody to which Wotan sings his Warning with its wide leaps and overall disjunct motion sounds a little bit like the motive representing Siegfried’s Sword.

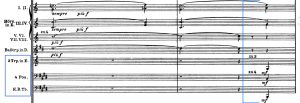

One final motive is prominent at the end of The Valkyrie, a motive which is referred to as Fate. It appears in the trombones and features three notes: a sustained pitch that slips down just one half step and then rises the small interval of a minor third to another sustained pitch.

Now that you’ve been introduced to all of the leitmotifs in this excerpt, follow along with the listening guide. As you listen, notice how prominent the huge orchestra is throughout the scene, how it provides the melodies, and how the strong and large voice of the bass-baritone singing Wotan soars over the top of the orchestra (Wagner’s music required larger voices than earlier opera as well as new singing techniques). See if you can hear the leitmotifs, there to absorb you in the drama. Remember that this is just one short scene from the midpoint of the approximately fifteen-hour-long tetralogy, The Ring Cycle.

Listening Guide

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, conducted by Pierre Boulez (recorded in 1980); bass-baritone Donald McIntyre as Wotan; soprano Gwyneth Jones as Brünnhilde

Composer: Richard Wagner (1813–1883)

Composition: Final scene: “Wotan’s Farewell” from The Valkyries

Date: premiered in 1870

Genre: music drama (or 19th-century German opera)

Form: through-composed, using leitmotifs

Nature of Text: original text in German. The following translation is taken from a score published in 1900.[1]

(He looks upon her and closes her helmet: his eyes then rest on the form of the sleeper, which he now completely covers with the great steel shield of the Valkyrie. He turns slowly away, then again turns around with a sorrowful look.)

(He strides with solemn decision to the middle of the stage and directs the point of his spear toward a large rock.)

Loge, hear! List to my word!

As I found thee of old, a glimmering flame,

as from me thou didst vanish,

in wandering fire;

as once I stayed thee, stir I thee now!

Appear! come, waving fire,

and wind thee in flames round the fell!

(During the following he strikes the rock thrice with his spear.)

Loge! Loge! appear!

(A flash of flame issues from the rock, which swells to an ever-brightening fiery glow.)

(Flickering flames break forth.)

(Bright shooting flames surround Wotan. With his spear he directs the sea of fire to encircle the rocks; it presently spreads toward the background, where it encloses the mountain in flames.)

He who my spearpoint’s sharpness feareth

shall cross not the flaming fire!

(He stretches out the spear as a spell. He gazes sorrowfully back on Brünnhilde. Slowly he turns to depart. He turns his head again and looks back. He disappears through the fire.)

(The curtain falls.)

Performing Forces: bass-baritone (Wotan) and large orchestra

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It uses leitmotifs.

- The orchestra provides an “unending melody” over which the characters sing.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Leitmotif and Form |

| 14:00 | Descending melodic line played loudly in octaves by the lower brass | Spear music: orchestra only |

| 14:10 | Wotan sings a motivic phrase with upward leaps that ascends. The orchestra also ascends, supporting his melodic line. | Wotan: Löge, hör! Lausche hieher! Wie zuerst ich dich fand, als feurige Glut, wie dann einst du mir schwandest, als schweifende Lohe; wie ich dich band. |

| 14:29 | Appears as Wotan transitions to new words still in the lower brass | Spear music. Wotan: Bann ich dich heut’! |

| 14:50 | Fire music starts. Then trills in the strings and a rising chromatic scale introduce Wotan’s striking of his spear and producing fire. | Fire music. Wotan: Herauf, wabernde Loge, umlodre mir feurig den Fels! Loge! Loge! Hieher! |

| 15:04 | Fire music with the upper woodwinds (flutes, oboes, and clarinets) playing the leading melody | Fire music: orchestra only |

| 15:41 | Slower, descending chromatic scale in the winds represents Brünnhilde’s descent into sleep. | Sleep music: orchestra only |

| 16:04 | As Wotan sings again, his melodic line seems to allude to the sword motive, doubled by the horns and supported by the full orchestra. | Sword motive. Wotan: Wer meines Speeres Spitze fürchtet, durchschreite das Feuer nie! |

| 16:34 | Lower brass prominently play the sword motive while the strings and upper woodwinds play motives from the fire music, with a gradual decrescendo. | Sword motive and fire music: orchestra only |

| 17:48 | The trombones play the narrow-raged fate melody supported by other brass instruments, and the curtain closes. | Fate motive: orchestra only |

- Wagner, Richard. Die Walküre. [English Transl. By Frederick Jameson; Version Française Par Alfred Eernst]. Leipzig: Eulenburg, 1900. Print. Eulenburgs kleine Partitur-Ausgabe. ↵