3. Music for Medieval Christian Worship

The earliest music of Catholic Christianity was chant, that is, monophonic a cappella music, most often sung in worship. As you learned in the first chapter of this book, monophony refers to music with one melodic line that may be performed by one or many individuals at the same time. Largely due to the belief of some Catholics that instruments were too closely associated with secular music, instruments were rarely used in medieval worship; therefore most chant was sung a cappella, or without instruments. As musical notation for rhythm had not yet developed, the exact development of rhythm in chant is uncertain. However, based on church tradition (some of which still exist), we believe that the rhythms of medieval chants were guided by the natural rhythms provided by the words.

Medieval Catholic worship included services throughout the day. The most important of these services was the Mass, at which the Eucharist, also known as communion, was celebrated (this celebration includes the consumption of bread and wine representing the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ). Five chants of the mass (the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei) were typically included in every mass, no matter what date in the church calendar. Catholics, as well as some Protestants, still use this Liturgy in worship today.

In the evening, one might attend a Vespers service, at which chants called hymns were sung. Hymns, like most of the rest of the Catholic liturgy, were sung in Latin. Hymns most often featured four-line strophes in which the lines were generally the same length and often rhymed. Each strophe of a given hymn was sung to the same music, and for that reason, we say that hymns are in strophic form. Hymns like most chants generally had a range of about an octave, which made them easy to sing.

altarpiece painted by Cimabue around 1280, via Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

Throughout the Middle Ages, Mary the mother of Jesus, referred to as the Virgin Mary, was a central figure in Catholic devotion and worship. Under Catholic belief, she is upheld as the perfect woman, having been chosen by God to miraculously give birth to the Christ while still a virgin. She was given the role of intercessor, a mediator for the Christian believer with a petition for God, and as such appeared in many medieval chants.

Focus Composition:

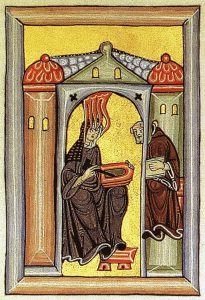

“Ave Generosa” by Hildegard of Bingen

Many composers of the Middle Ages will forever remain anonymous. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) from the German Rhineland is a notable exception. At the age of fourteen, Hildegard’s family gave her to the Catholic Church where she studied Latin and theology at the local monastery. Known for her religious visions, Hildegard eventually became an influential religious leader, artist, poet, scientist, and musician. She would go on to found three convents and become an abbess, the chief administrator of an abbey.

Writing poetry and music for her fellow nuns to use in worship was one of many of Hildegard’s activities, and the hymn “Ave Generosa” is just one of her many compositions. This hymn has multiple strophes in Latin that praise Mary and her role as the bearer of the Son of God. The manuscript contains one melodic line that is sung for each of the strophes, making it a strophic monophonic chant. Although some leaps occur, the melody is conjunct. The range of the melody line, although still approachable for the amateur singer, is a bit wider than other church chant of the Middle Ages. The melody also contains melismas at several places. A melisma is the singing of multiple pitches on one syllable of text. Overall, the rhythm of the chant follows the rhythm of the syllables of the text.

Chant is by definition monophonic, but scholars suspect that medieval performers sometimes added musical lines to the texture, probably starting with drones (a pitch or group of pitches that were sustained while most of the ensemble sang together the melodic line). Performances of chant music today often add embellishments such as occasionally having a fiddle or small organ play the drone instead of being vocally incorporated. Performers of the Middle Ages possibly did likewise, even if prevailing practices called for entirely a cappella worship.

Listening Guide

UCLA Early Music Ensemble; Soloist: Arreanna Rostosky; Audio & video by Umberto Belfiore

Listen through 3:17 for the first four strophes.

Composer: Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179)

Composition: “Ave Generosa”

Date: 12th century

Genre: hymn (a type of chant)

Form: strophic

Nature of Text: multiple, four-line strophes in Latin, praising the Virgin Mary.

See the full text and translation here.

Performing Forces: small ensemble of vocalists

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is chant.

- It is a cappella.

- Its rhythms follow the rhythms of the text.

- It is monophonic (although this performance adds a drone).

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic line is mostly conjunct.

- Its melody contains many melismas.

- It has a Latin text sung in a strophic form.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

| 0:00 | Solo vocalist enters with first line using a monophonic texture. The melody opens with an upward leap and then moves mostly by step: conjunct. |

Strophe 1: Ave, generosa, “Hail generous one” |

| 0:10 | Group joins with line two, some singing a drone pitch. The melody continues mostly conjunctly, with melismas added. Since the drone is improvised, this is still monophony. |

Strophe 1 continues: Gloriosa et intacta puella… “Noble, glorious, and whole woman…” |

| 0:49 | Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues). |

Strophe 2: Nam hec superna infusio in te fuit… “The essences of heaven flooded into you…” |

| 1:37 | Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues). |

Strophe 3: O pulsherrima et dulcissima… “O lovely and tender one…” |

| 2:34 | Repetition of the melody to new words sung by all with monophonic texture (the drone continues). |

Strophe 4: Venter enim tuus gaudium havuit… “Your womb held joy…” |

The Emergence of Polyphonic Music for the Medieval Church

Initial embellishments such as the addition of a musical drone to a monophonic chant were probably improvised during the Middle Ages. With the advent of musical notation that could indicate polyphony, composers began writing polyphonic compositions for worship, initially intended for select parts of the Liturgy to be sung by the most trained and accomplished of the priests or monks leading the mass. In the beginning, these polyphonic compositions featured two musical lines at the same time, and later the third and fourth lines were added. Polyphonic liturgical music, originally called organum, emerged in Paris around the late 12th and 13th centuries. In this case, growing musical complexity seems to parallel growing architectural complexity.

Composers wrote polyphony so that the cadences, or ends of musical phrases and sections, resolved to simultaneously sounding perfect intervals. Perfect intervals are the intervals of fourths, fifths, and octaves. Such intervals are called perfect because they are the first intervals derived from the overtone series (Chapter 1). As hollow and even disturbing as perfect intervals can sound to our modern ears, the Middle Ages used them in church partly because they believed that what was perfect was more appropriate for the worship of God than the imperfect.

In Paris, composers also developed an early type of rhythmic notation, which was important considering that individual singers would now be singing different musical lines that needed to stay in sync. By the end of the 14th century, this rhythmic notation began looking a little bit like the rhythmic notation recognizable today. At the beginning of a musical composition, a symbol was placed to indicate the meter, similar to the modern markings (Chapter 1). This symbol told the performer whether the composition was in two or in three and laid out the note value that provided the basic beat. Initially almost all metered church music used triple time, because the number three was associated with perfection and theological concepts such as the trinity.

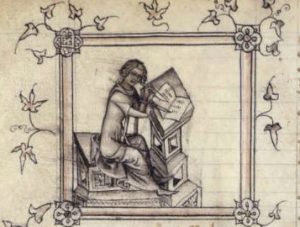

Elsewhere in what is now France, Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377) emerged as the most important poet and composer of this century. He is the first composer about whom we have much biographical information, due in part to the fact that Machaut himself, near the end of his life, collected his poetry into volumes of manuscripts. (A miniature image of the composer was also included in the volumes, Figure 2.8). We know that he traveled widely as a cleric and secretary for John, the King of Bohemia. Around 1340, he moved to Reims (now in France), where he served as a church official at the cathedral. There he had more time to write poetry and music, which he seemed to have continued doing for some time.

Focus Composition: “Agnus Dei” from the Messe de Nostre Dame (Mass of Notre Dame) by Guillaume de Machaut

We think that Machaut wrote his Messe de Nostre Dame (Mass of Notre Dame or Notre Dame Mass) around 1364. This composition is famous because it was one of the first compositions to set all five movements—the pieces of the Catholic liturgy included in every Mass, no matter what time of the year—of the mass ordinary as a complete whole. “Movement” in music refers to a musical section that sounds complete but that is part of a larger musical composition. Musical connections between each movement of this Mass cycle—the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei—suggest that Machaut intended them to be performed together, rather than being traded in and out of a Mass, based on the preferences of the priest leading the service. This Mass was likely performed every week in a side chapel of the Reims Cathedral. Medieval Catholics commonly paid for Masses to be performed in honor of their deceased loved ones.

As you listen to the “Agnus Dei” movement from the Notre Dame Mass, try imagining that you are sitting in that side chapel of the cathedral at Reims, a cathedral that looks not unlike the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Its slow tempo might remind us that this was music that memorialized the deceased loved ones or Machaut’s own brother (who died in 1372), and its triple meter allegorized perfection. Remember that although the perfect intervals in the music may sound disturbing to our ears, for those in the Middle Ages, they symbolized what was the most appropriate and musically innovative.

Listening Guide

Oxford Camerata directed by Jeremy Summerly

“Agnus Dei” starts at 24:52.

Composer: Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377)

Composition: “Agnus Dei” from the Notre Dame Mass

Date: c. 1364 CE

Genre: movement from the Ordinary of the Mass

Form: A-B-A

Nature of Text: Latin words from the Mass Ordinary

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis

(“Lamb of God, who takes away the sin, have mercy on us”)

Performing Forces: small ensemble of vocalists

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- It is part of the Latin mass.

- It uses four-part polyphony.

- It is in a slow tempo.

Other things to listen for:

- Its melodic lines have a lot of melismas.

- It is in triple meter, symbolizing perfection.

- It uses simultaneous intervals of fourths, fifths, and octaves, also symbolizing perfection.

- Its overall form is A-B-A.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture |

Text and Form |

| 24:52 | Small ensemble of men singing in four-part polyphony; a mostly conjunct melody with a lot of melismas in triple meter at a slow tempo. The section ends with a cadence on open, hollow-sounding harmonies such as octaves and fifths. | Section A: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

| 26:02 | This section begins with faster notes sung by the alto voice. Note that it ends with a cadence to hollowing-sounding intervals of the fifth and octave, just like the first section had. | Section B: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

| 27:18 | Same music as at the beginning | Section A: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, Miserere nobis |

Text set to a melody written in monophonic texture with un-notated rhythms typically used in religious worship.

Catholic celebration of the Eucharist consisting of liturgical texts set to music by composers starting in the Middle Ages.

Religious song, most generally having multiple strophes of the same number and length of lines and using strophic form.

Multiple pitches sung to one syllable of text.

The ending of a musical phrase providing a sense of closure, often through the use of one chord that resolves to another.