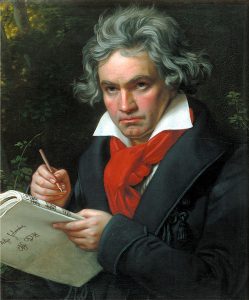

5. Music of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Beethoven was born in Bonn, a city near at the Western edge of the Germanic lands on the Rhine River, in December of 1770. Those in Bonn were well-acquainted with traditions of the Netherlands and of the French; they would be some of the first to hear of the revolutionary ideas coming out of France in the 1780s. The area was ruled by the Elector of Cologne. As the Kapellmeister (chapel choir master) for the Elector, Beethoven’s grandfather held the most important musical position in Bonn; he died when Beethoven was three years old. Beethoven’s father, Johann Beethoven, sang in the Electoral Chapel his entire life. While he may have provided Ludwig with music lessons at an early stage of his life, it appears that Johann had given in to alcoholism and depression, especially after the death of his wife and Ludwig’s mother, Maria Magdalena Keverich in 1787.

Although hundreds of miles east of Vienna, the Electorate of Cologne was under the jurisdiction of the Austrian Habsburg empire that was ruled from this Eastern European city. The close ties between these lands made it convenient for the Elector, with the support of the music-loving Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein (1762–1823), to send Beethoven to Vienna to further his music training. Ferdinand was the youngest of an aristocratic family in Bonn. He greatly supported the arts and became a patron of Beethoven. Beethoven’s first stay in Vienna in 1787 was interrupted by the death of his mother. In 1792, he returned to Vienna for good.

Perhaps the most universally known fact of Beethoven’s life is that he went deaf; and you can find a lot of writings on the topic. For our present purposes, the timing of his hearing loss is most important. It was at the end of the 1790s that Beethoven first realized that he was losing his hearing. By 1801, he was writing about it to his most trusted friends. It is clear that the loss of his hearing was an existential crisis for Beethoven. During the fall of 1802, he composed a letter to his brothers that included his last will and testament, a document that we have come to know as the Heiligenstadt Testament, named after the small town of Heiligenstadt, north of the Viennese city center, where he was staying. The Testament provides us insight to Beethoven’s heart and mind. Most striking is his statement that his experiences of social alienation, connected to his hearing loss, “drove me almost to despair, a little more of that and I would have ended my life—it was only my art that held me back.” The idea that Beethoven found in art a reason to live suggests both his valuing of art and a certain self-awareness of what he had to offer in music. Beethoven and his physicians tried various means to counter the hearing loss and improve his ability to function in society. By 1818, Beethoven’s deafness had progressed to the point where he frequently needed to use “conversation books” for people to write down their side of conversations with him. He still retained some hearing in his left ear and could hear, although faintly, until shortly before his death in 1827.

Beethoven had a complex personality. Although he read the most profound philosophers of his day and was compelled by lofty philosophical ideals, his own writing was broken and his personal accounts show errors in basic math. He craved close human relationships yet had difficulty sustaining them. By 1810, he had secured a lifetime annuity from local noblemen, meaning that Beethoven never lacked for money. Still, his letters, as well as the accounts of contemporaries, suggest a man suspicious of others and preoccupied with the compensation he was receiving.

Overview of Beethoven’s Music

Upon arriving in Vienna in the early 1790s, Beethoven supported himself by playing piano at salons and by giving music lessons. Salons were gatherings of literary types, visual artists, musicians, and thinkers, often hosted by noblewomen for their friends. Here Beethoven both played music of his own and improvised upon musical themes given to him by those in attendance.

In April of 1800, Beethoven gave his first concert for his own benefit, held at the important Burgtheater, Vienna. As typical for the time, the concert included a variety of types of music: vocal, orchestral, and chamber music. Many of the selections were by Haydn and Mozart, for Beethoven’s music from this period was profoundly influenced by these two composers.

Scholars have traditionally divided Beethoven’s composing into three chronological periods: early, middle, and late. Like all efforts to categorize, this one proposes boundaries that are open to debate. Probably most controversial is the dating of the end of the middle period and the beginning of the late period. Beethoven did not compose much music between 1814 and 1818, so any division of those years would fall more on Beethoven’s life than on his music.

In general, the music of Beethoven’s first period (roughly until 1803) reflects the influence of Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven’s second period (1803-1814) is sometimes called his “heroic” period, based on his recovery from depression documented in the Heiligenstadt Testament. This period includes music compositions such as his Symphony No. 3, which Beethoven subtitled “Eroica” (heroic), Symphony No. 5, and his only opera, Fidelio, which took the French revolution as its inspiration. Other works composed during this time include Symphonies No. 4 through No. 8 and some well-known piano works, such as the sonatas “Waldstein,” “Appassionata,” and “Lebewohl”, and Piano Concertos No. 4 and No. 5. He also composed instrumental chamber music, choral music, and songs. In these works of his middle period, Beethoven is often regarded as having come into his own because they display a new and original musical style. In comparison to the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven’s earlier period, these longer compositions feature larger performing forces, thicker polyphonic textures, more complex motivic relationships, more dissonance and delayed resolution of dissonance, more syncopation and hemiola (the momentary simultaneous sense of being in two meters at the same time), and more elaborate forms.

When Beethoven started composing again in 1818, his music was much more experimental. Some of his contemporaries believed that he had lost his ability to compose as he lost his hearing. The late piano sonatas, last five string quartets, monumental Missa Solemnis, and Symphony No. 9 in D minor (The Choral Symphony) are now perceived to be some of Beethoven’s most revolutionary compositions, although they were not uniformly applauded during his lifetime. Beethoven’s late style was one of contrasts: extremely slow music next to extremely fast music; and extremely complex and dissonant music next to extremely simple and consonant music.

Although this chapter will not discuss the music of Beethoven’s early period or late period in any depth, you might want to explore this music on your own. Beethoven’s first published piano sonata, the Sonata in F minor, Op. 2, No. 1 (1795), shows the influence of its dedicatee, Joseph Haydn. One of Beethoven’s last works, his famous Symphony No. 9, departs from the norms of the day by incorporating vocal soloists and a choir into a symphony, which traditionally was almost always written only for orchestral instruments. Symphony No. 9 is Beethoven’s longest symphony; its first three movements, although innovative in many ways, were written the expected forms: a fast sonata form, a scherzo (which by the early 19th century—as we will see in our discussion of his Symphony No. 5—had replaced the minuet and trio), and a slow theme and variations form. The finale, in which the vocalists participate, is truly revolutionary in terms of its length, the sheer extremes of the musical styles it uses, and the combination of large orchestra and choir. The text that Beethoven chose to set his music to was a poem An die Freude (Ode to Joy) written by Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805). It speaks of joy and the hope that all humankind might live together in brotherly love.

Focus Composition: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67

The premier of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 took place at perhaps the most infamous of all of Beethoven’s concerts, an event that lasted for some four hours in an unheated theater on a bitterly cold Viennese evening in December 1808. At this time, Beethoven was not on good terms with the performers, several of whom refused to rehearse with the composer in the room. In addition, the final number of the performance was finished too late to be sufficiently practiced, and in the concert, it had to be stopped and restarted. Belying its less than auspicious first performance, once published the Symphony quickly gained the critical acclaim that it has held ever since.

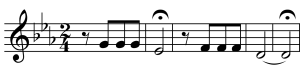

The most famous part of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is its commanding opening. This opening features the entire orchestra playing in unison a musical motive that we will call the short-short-short-long (SSSL) motive, because of the rhythm of its four notes. We will also refer to it as the “fate motive,” because at least since the 1830s, music critics have linked it to fate knocking on the door. The first movement is in sonata form. In the exposition, the three short notes repeat the same pitch and then the long, held-out note leaps down a third. After the orchestra releases the held note, it plays the motive again, now sequenced a step lower, then again at the original pitches, then at higher pitches. This sequenced phrase, which has become the first theme of the movement, then repeats, and the music starts to pick up steam. After a transition, the second theme is heard. It also starts with the SSSL motive, although the pitches heard are quite different. The horn presents the question phrase of the second theme; then, the strings respond with the answer phrase of the second theme. You should note that the key has changed—the music is now in E flat major, which has a much more peaceful feel than C minor—and the answer phrase of the second theme is much more legato and lyrical than anything heard in the symphony so far. This tuneful legato music does not last for long and the closing section returns to the rapid sequencing of the SSSL motive. The development section of the movement does everything we might expect of a development: the SSSL motive appears in sequence and is altered as the keys change rapidly. Also, we hear more polyphonic and imitative textures in the development than elsewhere in the movement. Near the end of the development, the dynamics alternate between piano and forte, and before long, the music has returned to the home key (C minor) as well as the opening version of the SSSL motive, which is the start of the recapitulation. The music transitions to the second theme, followed by the closing section. Then, just when we expect the recapitulation to end, Beethoven extends the movement with a coda. This coda is much longer than any coda we have listened to in the music of Haydn or Mozart, although it is not as long as the coda to the final movement of this symphony. These long codas are also another element that Beethoven is known for. He often restates the conclusive cadence many times and in many rhythmic durations.

The second movement is a lyrical theme-and-variations movement in a major key, which provides a few minutes of respite from the menacing C minor. If you listen carefully, though, you might hear some reference to the SSSL fate motive.

The third movement returns to C minor and is a scherzo. Scherzos retain the form of the minuet and trio, having a contrasting trio section that divides the two presentations of the scherzo. Like the minuet, scherzos are also in triple time, although they tend to be somewhat faster in tempo than the minuet. This scherzo movement opens with a mysterious, even spooky, opening theme played by the lower strings. The second theme returns to the SSSL motive, although now with different pitches. The mood changes with a very imitative and very polyphonic trio section in C major, but the spooky theme reappears, alongside the fate motive, to start the written-out, altered repeat of the scherzo. Instead of making the scherzo a discrete movement, Beethoven chose to write a musical transition between the scherzo and the final movement, so that the music runs continuously from one movement to another. After suddenly getting very soft, the music gradually grows in dynamic as the motive sequences higher and higher until the fourth movement bursts onto the scene with a triumphant and loud C major theme. It seems that perhaps our hero, whether we think of the hero as the music of the symphony or perhaps as Beethoven himself, has finally triumphed over Fate.

The fourth movement is a rather typical fast sonata-form finale with one exception. The second theme of the scherzo, which contains the SSSL fate motive, appears one final time at the end of this movement’s development section, as if to try one more time to derail the hero’s conquest. But, the movement ultimately ends with a lot of loud cadences in C major, providing ample support for an interpretation of the composition as the overcoming of Fate. This is the interpretation that most commentators for almost two hundred years have given the symphony. It is pretty amazing to think that a musical composition might express so aptly the human theme of struggle and triumph.

Listening Guide

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (on period instruments), conducted by John Eliot Gardiner

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Composition: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

Date: 1808

Genre: symphony, orchestral music

Form: four movements as follows:

I. Allegro con brio – fast, sonata form

II. Andante con moto – slow, theme and variations form

III. Scherzo. Allegro – scherzo and trio form

IV. Allegro – fast, sonata form

Performing Forces: orchestra with piccolo (fourth movement only), two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon (fourth movement only), two horns, two trumpets, three trombones (fourth movement only), timpani, and strings (first and second violins, viola, cellos, and double basses)

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- Its fast first movement in sonata form opens with the short-short-short-long motive (which pervades much of the symphony): Fate knocking at the door?

- The symphony starts in C minor but ends in C major: a triumph over fate?

I. Allegro con brio

Also see the guided analysis by Gerard Schwarz of the first movement as well as his analysis of this movement from an orchestra conductor’s perspective.

What we want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a fast movement in sonata form, opening with the short-short-short-long motive.

- It starts in C minor, modulates for a while to other keys, but returns to C minor at the end of the movement.

- The staccato first theme, comprised of sequencing of the short-short- short-long motive, greatly contrasts the more lyrical and legato second theme.

- The coda at the end of the movement provides a dramatic closure.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 0:00 | Full orchestra in a mostly homophonic; melody starting with the SSSL motive loudly and then suspended with a fermata (or hold); after two pauses, the melody continuing with the SSSL motive in rising sequences in a quieter dynamic; dynamics gradually growing louder until a forte holding note | Exposition: First theme |

| 0:21 | Falling sequences using the SSSL rhythm at a quiet dynamic; growing louder again with the timpani joining the force | Transition |

| 0:40 | A horn call using the SSSL motive to introduce the strings playing a quieter, more lyrical theme, followed by the winds, now in a major key | Second theme |

| 1:00 | Full orchestra at forte playing brightly; SSSL rhythms passed from one set of instruments to another in downward sequences; finished in a major key | Closing |

| 1:17 | Exposition repeated | |

| 2:32 | Some polyphonic imitation; lots of dialogue between the low and high instruments and the strings and winds; rapid sequences and changing of keys; fragmentation and alternation of the original motive | Development |

| 3:33 | Music moves from fortes to pianos | Retransition |

| 3:45 | Starting like the exposition, but the theme ends with a short oboe cadenza | Recapitulation: First theme |

| 4:10 | Similar to the transition in the exposition but does not modulate | Transition |

| 4:29 | The “horn” call now played by the bassoons, followed by the strings and winds playing the second theme | Second theme |

| 4:53 | As above; in C major | Closing |

| 5:08 | A new section growing out of a cadence; rising dynamics, interrupted by the motive played by much fewer instruments; shifting back to C minor; a new melody introduced; first theme played again, followed by a suddenly piano, legato, varied theme played by the winds; suddenly loud SSSL motives again to end the movement in bombastic manner: Fate threatens | Coda |

II. Andante con moto

Also see the guided analysis by Gerard Schwarz of the second movement.

What we want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a slow theme-and-variations movement.

- Its major key provides contrast from the minor key of the first movement.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 6:31 | Mostly homophonic; consisting of two themes, the first (a) more lyrical and the second (b) more march-like | Theme: a and b |

| 8:11 | More legato and softer at the beginning, although growing loud for the final statement of theme b in the brass before getting quieter to piano again where violas subdivide the beat with fast running notes, while the other instruments play the theme | Variation 1: a and b |

| 9:46 | There are more rapid subdivision of the beat in the lower strings at the beginning of theme a, and the theme is expanded and becomes longer than the previous ones. Theme b starts near the end of the variation. | Variation 2: a and b |

| 11:59 | Lighter in texture and more staccato, starting piano and getting louder to forte for the next statement of theme a, played by the full orchestra; motives traded by different sections of the orchestra at a quieter dynamic | Variation 3: a |

| 13:14 | Starts at a faster tempo, led by the bassoon and then other woodwinds at a quieter dynamic; full orchestra entering, gradually getting louder; returning to the original tempo and motives of the themes played and re-emphasized to conclude the movement | Coda |

III. Scherzo. Allegro

Also see the guided analysis by Gerard Schwarz of the third and four movements.

What we really want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a scherzo movement that has a scherzo (A)–trio (B)–scherzo (A) form.

- The short-short-short-long motive returns in the scherzo sections.

- The scherzo section is mostly homophonic and the trio section is mostly imitative polyphony.

- It flows directly into the final movement without a break.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 14:46 | Theme a, ascending legato melody, led by the lower strings at a quiet dynamic | Scherzo (A): a |

| 15:04 | Theme b, Fate motive, presented first by the brass in a forte dynamic | b |

| 15:19 | Theme a and theme b; overlapping of motives from both themes | a b a b |

| 16:17 | Fast theme c, led by the lower strings and joined later by bassoon; theme d, an expansion of theme c with polyphonic imitation at a quieter dynamic | Trio (B): c c d d |

| 17:34 | Scherzo (A) repeated | |

| 19:06 | Trio (B) repeated | |

| 20:24 | Very soft dynamic in the beginning, recalling theme a (legato then staccato/pizzicato); theme b (Fate motive) quietly played by the oboe, with plucked strings; transitioning into the fourth movement with ascending motivic sequences in slow crescendo, followed by the full orchestra performing a more rapid crescendo and a gradual tempo change | Trio (A) and Transition |

IV. Allegro

What we want you to remember about this movement:

- It is a fast sonata-form movement in C major.

- The SSSL motive via the scherzo “b” theme returns one final time at the end of the development.

- The trombones, for their first appearance in a symphony to date.

- It has a very long coda.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 21:58 | Triumph triadic theme in C major, forte and played by the full orchestra, including trombones, contrabassoon, and piccolo | Exposition: First theme |

| 22:31 | Full orchestra, led by the brass and then continued by the strings; the opening motive of this transition sequenced as the music modulates away from the key | Transition |

| 22:55 | Full orchestra, slightly softer in dynamic; still triumphant, if more lyrical, using triplet rhythms in the melody, in G Major | Second theme |

| 23:21 | Repetitions of a descending theme | Closing theme |

| 23:50 | Exposition repeated | |

| 25:42 | Motives passed through all sections of the orchestra: the triplet motive from the second theme and then the rhythmic motive from the opening theme; Fate motive | Development |

| 27:08 | Quiet dynamic and thinner texture; winds playing the Fate motive from the Scherzo; strings repeating the motive | Return of scherzo theme |

| 27:38 | Performing forces are as in the exposition | Recapitulation: First theme |

| 28:11 | Does not modulate. | Transition |

| 28:39 | In C major | Second theme |

| 29:04 | Started with the woodwinds and then played forte by the whole orchestra | Closing theme |

| 29:31 | Lengthy section starting with the triplet motive, and proceeding through with a lot of repeated cadences emphasizing C major and repetition of other motives until the final repeated cadences Note the dramatic pauses, alternation of contrasting articulations (legato and staccato), sudden increase in tempo near the conclusion, full orchestra with prominent presence of a piccolo, use of forte dynamic. |

Coda |

Finally, also see Leon Botstein’s “An Appreciation” of Beethoven and his Symphony.

Enjoy a more recent video recording of the Symphony performed by Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and John Eliot Gardiner.