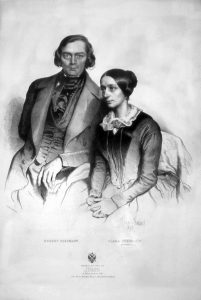

5. Music of Robert Schumann (1810–1856) and Clara Schumann (1819–1896)

Husband and wife Robert and Clara Schumann were another prominent musical pair of the 19th century. The couple became acquainted after Robert Schumann (1810-1856) moved to Leipzig and started studying piano with Friedrich Wieck, the father of the young piano prodigy Clara Wieck (1819-1896). The nine-year-old Clara was just starting to embark on her musical career. Throughout her teens, she would travel giving concerts, dazzling aristocratic and public audiences with her virtuosity. She also started publishing her compositions, which she often incorporated into her concerts. Her father, perhaps realizing what marriage would mean for the career of his daughter, refused to consent to her marriage with Robert Schumann, a marriage she desired as she and Robert had fallen in love. They subsequently married in 1840, shortly before Clara’s twenty-first birthday, after a protracted court battle with her father.

Once the two were married, Robert’s musical activities became the couple’s first priority. Robert Schumann began his musical career with aims of becoming a professional pianist. When he suffered weakness of the fingers and hands, he shifted his focus to music journalism and music composition. He founded a music magazine dedicated to showcasing the newer and more experimental music composed then. He started writing piano compositions, songs, chamber music, and eventually orchestral music, the most important of which include four symphonies and a piano concerto (premiered by Clara in 1846). While Robert was gaining recognition as a composer and conductor, Clara’s composition and performance activities were restricted by her giving birth to eight children. Then in early 1854, Robert started showing signs of psychosis and, after a suicide attempt, was taken to an asylum. Although one of the more progressive hospitals of its day, this asylum did not allow visits from close relatives, so Clara would not see her husband for over two years and then only in the two days before his death. After his death, Clara returned to a more active career as performer; she spent the rest of her life supporting her children and grandchildren through her public appearances and teaching. Her busy calendar may have been one of the reasons why she did not compose after Robert’s death.

The compositional careers of Robert and Clara followed a similar trajectory. Both started their compositional work with short piano pieces that were either virtuoso showpieces or reflective character pieces that explored extra musical ideas in musical form. Theirs were just a portion of the many character pieces, especially those at a level of difficulty appropriate for the enthusiastic amateur pianist, published throughout Europe. After their marriage, they both merged poetic and musical concerns in Lieder—Robert published many song cycles, and he and Clara joined forces on a song cycle published in 1841. They also both turned to traditional genres, such as the sonata and larger four-movement chamber music compositions.

Focus Composition: “Chiarina” from Carnaval

Robert Schumann’s “Chiarina,” was written between 1834 and 1835, and published in 1837 in a cycle of piano character pieces that he called Carnaval, after the festive celebrations that occurred each year before the beginning of the Christian season of Lent. Each short piece in the collection has a title, some of which refer to imaginary characters that Robert employed to give musical opinions in his music journalism. Others, such as “Chopin” and “Chiarina,” refer to real people, the former referring to the popular French-Polish pianist Fryderyk Chopin, and the later referring to the young Clara. At the beginning of the “Chiarina,” Robert inscribed the performance instruction passionata, meaning that the pianist should play the piece with passion. “Chiarina” is little over a minute long and consists of a two slightly contrasting musical phrases.

Listening Guide

Daniel Barenboim, piano

Composer: Robert Schumann (1810- 1856)

Composition: “Chiarina” from Carnaval

Date: published in 1837

Genre: character piece for solo piano

Form: a a b a’ b a’

Nature of Title: “Chiarina” refers to Clara.

Performing Forces: solo piano

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- This is a character piece for solo piano.

- A dance-like mood is conveyed by its triple meter and moderately fast tempo.

Other things to listen for:

- It has a leaping melody in the right hand and is accompanied by chords in the left hand.

- It is composed of two slightly different melodies.

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 0:00 | Forte rising, leaping melody, in homophonic texture throughout | a |

| 0:09 | Fortissimo (very loud) rising, leaping melody now doubled in octaves | a |

| 0:18 | Mezzo-forte melody that has leaps but a smaller range and descends slightly | b |

| 0:27 | Played once and then crescendos as a it is repeated in octaves | a’ |

| 0:46 | Melody has leaps but a smaller b range and descends slightly | b |

| 0:57 | Played once and then repeated in octaves | a’ |

Focus Composition: Ballade in D minor, Op. 6, No. 4

Clara Schumann’s Ballade in D minor was written between 1834 and 1836, and published as one piece in the collection Soirées Musicales in 1836 (a soirée was an event generally held in the home of a well-to-do lover of the arts where musicians and other artists were invited for entertainment and conversation). The meaning of the title “ballade” seems to have been vague almost by design, but, most broadly considered, a ballade refers to a composition thought of as a narrative. As a character piece, it tells its narrative completely through music. Several contemporary composers wrote ballades of different moods and styles; and this ballade composed by Clara Schumann shows some influence of Chopin.

The Ballade in D minor has a homophonic texture and starts in a minor key. A longer piece than “Chiarina,” the ballade modulates to D major, before returning to D minor for a reprise of the A section. Its themes are not nearly as clearly delineated as the themes in “Chiarina”; instead, phrases start multiple times, each time slightly varied. You many hear what we call musical embellishments, notes the composer adds to a melody to provide variations. You might think of them like jewelry on a dress or ornaments on a Christmas tree. One of the most famous sorts of ornaments is the trill, in which the performer rapidly and repeatedly alternates between two pitches. We also talk of turns, in which the performer traces a rapid stepwise ascent and descent (or descent and ascent) for effect. You should also note that as the pianist in this recording plays, he seems to hold back notes at some moments and rush ahead at others: this is called rubato, that is, the robbing of time from one note to give it to another. We will see the use of rubato even more prominently in the music of Chopin.

Listening Guide

Jozef de Beenhouwer, piano

Composer: Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896)

Composition: Ballade in D minor, Op. 6, No. 4 (at 10:21), from Soirées Musicales

Date: published in 1836

Genre: character piece for solo piano

Form: A B A

Nature of Title: ballade, a composition with narrative premises

Performing Forces: solo piano

What we want you to remember about this composition:

- A lyrical melody over chordal accompaniment making this homophonic texture

- A moderate to slow tempo

- In quadruple time but also giving a feel of two-beat pulse, especially in the B section

Other things to listen for:

- Musical themes that develop and repeat but varied

- Musical embellishments in the form of trills and turns

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Form |

| 10:21 | Theme, in D minor, starts three times before taking off. Melody ascends and uses ornaments for variations. Quiet dynamics, slow tempo, quadruple time | A |

| 11:15 | Transitional idea using trills (extended ornaments); tempo picking up a little | |

| 11:45 | New thematic idea repeated a couple of times with variation; crescendo ascending phrases and decrescendo descending phrases | |

| 12:30 | Transitional idea returns. Slightly louder | |

| 12:45 | Repeated-note motive from the first theme; more passionate and louder then subsiding in dynamics | |

| 13:10 | New theme in D major, generally brighter; pulse of duple time; extended ornaments in the left-hand accompaniment; broader dynamic changes; marked tempo changes towards the end of the section | B |

| 14:42 | First theme returns in D minor and then is varied. Dynamic changes from piano to fortissimo, and then return to piano; tempo changes | A’ |

| 15:42 | Return of motives from the B-section theme, in minor; ambiguous tonality towards the end; ending with a D-major chord, very quietly and in a slowed tempo | Coda |