13 The Power Of A Unique Positioning Statement

By Margie Kuo Permanlink missing above

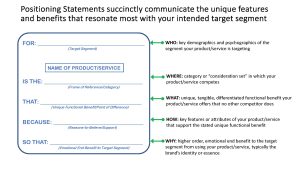

Positioning Statements succinctly communicate the unique features and benefits that resonate most with your intended target segment.

POSITIONING STATEMENT DEFINED

Plainly stated, positioning is the space occupied by a brand vis-à-vis its competition, in the target customer’s mind. It is not just the perception of “what a product does and who it is for,” but also how it is meaningfully differentiated from the competition. Positioning is how a marketer wants their target customer to view their brand. It may not be how the customer currently views the brand, but it is the intended goal.

A positioning statement is just the succinct communication of the key features and benefits that are most important to your target customer. A strong positioning statement is unique to that brand and that brand alone, i.e., no other brand should be able to occupy or own the space described. The real test is to check to see if any other brand can make the same positioning statement. If they can, then the positioning statement is not unique enough, and therefore, the brand’s positioning in your target’s mind is not clear. When your brand’s positioning is not clear, the brand is perceived as interchangeable with another brand, making it much easier for your target customer to switch to your competition.

COMPONENTS OF A POSITIONING STATEMENT

Positioning Statements typically have six distinct components (“FOR,” “BRAND,” “IS THE,” “THAT,” “BECAUSE,” and “SO THAT”) and read like one complete sentence when finalized. A positioning statement always starts with identifying the primary target audience or segment to whom you intend to promote or market your product.

1) The “FOR” component calls for a clear target segment description that includes both demographics (e.g., age, gender, education, etc.) and psychographics (e.g., attitudes, values, lifestyles, etc.). While marketers would like everyone to use their product or service, there is always one segment that is most important, profitable, valuable, and/or easier to attract; this is your target segment. Identifying this target segment’s demographics and psychographics requires conducting primary research with potential customers to uncover the extent of their unmet needs and barriers to trying, switching, or staying with your brand.

2) The second component, “BRAND,” is simply the name of your product or service.

3) This is followed by the “IS THE” component, the frame of reference, market segment, or category in which your brand competes. This defines your competitive set: indirect and direct competitors. The more specific it is, the clearer you are about who your competition is. The goal is to define the frame of reference in such a way that it encompasses and acknowledges your direct and indirect competition. For example, in the automotive example, defining the competitive set for a given target segment as just “cars” is too broad. “Luxury vehicles” or “SUVs” would be a clearer description of the segment and the competitors the brand is competing against.

4) The fourth section/component, “THAT,” should reflect the unique, functional (“what does it do”) benefit that your brand delivers and one that matters most to your target segment. If a benefit is unique to your brand, but not important to your target segment, then it does not belong here. If another brand can make the same claim, then it is not ownable and weakens your brand’s positioning. Additionally, what goes in this section should clearly be the unique benefit delivered by the brand, not to be confused with the features that support this functional benefit. A simple way to differentiate between features and benefits: features “tell” and benefits “sell.”

5) The fifth section/component, “BECAUSE,” should reflect the key features that directly support the unique, functional benefit listed in “THAT.” These features are the “reasons-to-believe” (RTBs) that this brand can deliver the unique functional benefit that the target segment is seeking. It is tempting to laundry-list a brand’s features here, but a strong positioning statement should include only the most relevant features that research has shown to support and ladder up to the unique, functional benefit the brand claims to deliver.

6) Finally, the last section/component, “SO THAT,” should reflect the emotional benefit to the target segment in the “FOR” component, not to the brand. The positioning statement is from the perspective of the target segment, not the brand. Additionally, this should be distinctly different from the functional benefit listed above. Functional benefit is about what the brand tangibly does; emotional benefit is about how the brand makes the target segment feel using it.

As shown below, the positioning statement outline answers six questions that when written out summarize the key practical and emotional benefits that give your brand a competitive edge.

|

6 Components of a Positioning Statement |

Each component should be the answer to the following questions: |

|

WHO? Key demographics and psychographics of the segment your product or service is targeting.

|

|

WHICH? Name of the product or service.

|

|

WHERE?: The category or “consideration set” in which your product or service competes.

|

|

WHAT? The unique, tangible, differentiated functional benefits your product or service offers that no other competitor does

|

|

HOW? Key features or attributes of your product or service that support the stated unique functional benefit.

|

|

WHY? The higher order emotional end benefit that the target gains from using your product or service. Typically this can also be the brand’s identify or essence. |

|

|

|

APPLICATION

Positioning statements are foundational elements of campaign creative briefs. The most effective creative briefs include the elements of a positioning statement or the statement itself. Without a clear sense of whom you are targeting, what unique functional benefit you are promoting to this target, and a firm understanding of the emotional benefit the target needs to experience to choose your brand over another, a campaign and the brand itself are doomed to fail. No creative brief should even be started or attempted until a clear, ownable positioning statement has been developed and tested.

Every key decision-maker should have their own positioning statement. In the automotive industry, there are the customers who purchase the car, but there are also intermediaries, like car dealerships, as well as manufacturers of the car. Similarly, in the health care industry, there are the patients who purchase a medication or procedure, the health care professionals who prescribe the medication or perform the procedure, and the insurers who decide which medications and procedures and how much of their costs are covered. For each of these specific key decision-makers in the industry and category your brand competes in, a unique positioning statement should be created as each decision-maker is motivated by different features and benefits.

COMMON MISTAKES

Finally, beware of some common mistakes that result in fuzzy, ineffectual positioning statements.

Mistake #1: Trying to appeal to all people, already satisfied people, or too few people.

To paraphrase a common saying, when you try to be all things to all people, you end up being nothing to anyone. If the target audience in your “FOR” component is too broad, e.g., only demographics or only psychographics, this makes it hard to focus on the most important features and benefits that the brand should emphasize. By definition, target segments are motivated by different features and benefits that underpin their willingness to purchase. If a competitor already has a stronghold on a target segment, objectively assess how satisfied this segment truly is with the competitor, and what type or magnitude of functional and emotional benefits your brand would need to offer to entice your target segment to switch. Conversely, if your target audience is too narrow or niche, there may not be enough potential customers in that segment to justify the investment and marketing effort to reach and convert them into customers. Qualitative and quantitative research should be initiated to accurately identify the target segments that are large enough, still unsatisfied with current offerings, and willing to pay and/or overcome hurdles to try or switch to your brand.

Mistake #2: Defining too broad or too narrow of a competitive set or category.

The competitive frame of reference or competitive set you choose for the “IS THE” component defines the category or market segment in which your brand competes. It should not contain any descriptors unique to your brand/product, except those for the other sections. This section describes the competitive set to which your target segment will compare your brand’s functional and emotional benefits.

Mistake #3: Focusing on a functional benefit that other brands already offer or do better.

Brands have multiple functional benefits, and many are just the price-of-entry: all viable automobiles need to be able to get you from A to B faster than most other forms of transportation; all disposable paper towels need to soak up spills. The functional benefit you choose to feature in the “THAT” component of your positioning statement should reflect the most important one to the target and the one your brand delivers uniquely better than other brands. A unique functional benefit is one that your brand truly “owns” and is meaningful enough to a target segment to motivate them to choose your brand over another. A good test is to objectively assess whether a competitor can also deliver the same functional benefit just as well as or cheaper, faster, or better than your brand. If the answer is yes, it is not a unique functional benefit. If the functional benefit is technically unique but can be easily improved upon or copied, then it is not sustainable or ownable enough to be included in a positioning statement, or you risk having to revise your positioning statement every time a competitor one-ups your brand.

Mistake #4: Confusing a functional benefit as your target’s emotional benefit.

Finally, probably the most challenging element of a positioning statement to nail down is the emotional benefit of your brand to your target segment, the “SO THAT.” A common mistake is to include a benefit that is actually a functional benefit. If your “SO THAT” sounds similar to your “THAT,” it is not an emotional benefit. A good way to identify the emotional benefit of your brand to your target is to ask how you want the target to feel when using your brand; it should be a higher order benefit. The unique functional benefit for a luxury vehicle might be “drives like a German-engineered F1 sports car,” but the emotional benefit for the target might be “make an entrance every time, letting others know you’ve ‘arrived.’” Another common mistake is writing the emotional benefit from the perspective of the brand versus the perspective of the target in the “FOR” section.

Below is an example of how we might fill out a chart for a high-end carry-on bag. As shown below, the positioning statement outline answers six questions that when written out, summarize the key practical and emotional benefits that give your brand a competitive edge.

Positioning Statement (Downloadable PDF)