1 1.1. What Is Psychology?

Jill Grose-Fifer

Psychology is the study of the mind (thoughts and feelings) and behavior (what we do). Unequal distribution of wealth and resources across the United States and in many other countries in the world leads to vastly different opportunities and experiences for people, depending on who they are, and where they live. Not surprisingly, these lived experiences interact with biological (and other individual factors) determining how people think, feel, and behave in different situations.

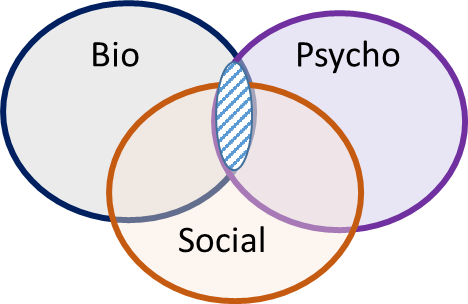

Psychologists often use a biopsychosocial lens (see Figure 1.4) to try to better understand people’s behaviors, and their thoughts and feelings. In other words, they look at the influence of biological, psychological, and social factors. Biological factors include looking at the impact of genes, nervous system function, and physical health. Psychological factors include significant life events relating to mental health, emotion, distress, beliefs, and expectations. Finally, social influences include interpersonal factors, such as social interactions, community experiences, and culture. Clearly, what we do, think, and feel at any given moment is highly context-dependent and psychologists are increasingly recognizing the importance of studying contextual influences such as ethnicity, race, ability, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and other cultural norms. However, it is also important to recognize that modern-day Western psychology has been dominated by research in the United States and Europe with foundational studies by White middle-class males.

At first glance, the research conducted by Western psychologists appears to be highly objective. Psychologists frequently employ the scientific method using statistics to test their predictions. Also, psychologists typically publish their findings in scientific journals after review by other experts in the field, a process known as peer review. This is done to try and ensure quality control. However, Western Psychology has also tended to make universal claims about all humans based on studies of a very small percentage of the world population – often referred to as WEIRD participants, i.e., mostly White undergraduates from educated, industrialized, rich democracies, such as the United States and Europe (Apicella et al., 2020). Furthermore, if other groups of people behaved, thought, or felt differently from the published “norms”, Western psychologists have often considered them atypical or deficient. However, psychologists much less frequently questioned whether they (and the studies they conducted) were culturally biased. In addition, more recent attempts to reproduce many of the original research studies in Western psychology have not always succeeded – leading to what has been termed the replication crisis in psychology (and science more broadly). When you read about the many different ways that modern psychologists carry out research in the upcoming chapter on Research Methods, you will see that there are many reasons for this lack of replication. All of these issues call into question the validity of some “foundational” studies in traditional Western Psychology. However, the field of psychology is becoming more critical of its roots. As more women and people of color have broken through barriers and became psychologists, priorities have shifted and the diversity of the human experience has become increasingly important to the field of psychology (you will read more about this in the section on Social Justice and Intelligence). Many psychologists are now acknowledging that Western Psychology has been highly ethnocentric, that is evaluating people from the context of one’s own culture, and not necessarily relevant to the global majority.

All of this might sound confusing and maybe even slightly worrying to a new student of psychology, but we encourage you to think of yourself as standing at an exciting crossroad in the discipline. Psychologists and students of psychology are becoming increasingly aware and critical of shortcomings in the field, including the role that Western psychology has played in oppressing people historically considered to be at the margins of society. But, we also have the chance to reimagine the discipline, to move away from outdated theories that fail to capture the breadth of the human experience, and instead to embrace research that offers a more contextualized, nuanced, and representative view of people’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Therefore, in this book, although we have reused open source materials, we also provide some pointed critiques about the “traditional canon of knowledge” in Western psychology, and we strongly encourage you to think of more. We have also tried to broaden our coverage beyond traditional textbooks, to include and uplift perspectives from Black, Latinx, and Asian-American psychology, and to highlight the importance of critical race, intersectionality, feminist, and queer theories in understanding humankind. Thirdly, we have tried to infuse a social justice focus throughout this text to show how psychology can promote equality and fight against oppression (see Figures 1.5 and 1.6). In short, we have tried hard to introduce you to the good, bad, and the ugly in the field of psychology in the hope that you will think deeply about how to use this knowledge to improve your life and the lives of other people. Finally, we acknowledge that despite our lofty goals, this book (and its associated materials) are a work in progress and we welcome your feedback and any suggestions for improvements. Please email us at jgrose-fifer@jjay.cuny.edu