12 Social Psychology

CHAPTER OUTLINE

12.1 What is Social Psychology?

12.2 Self-presentation

12.3 Attitudes and Persuasion

12.4 Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

12.5 Prejudices and Discrimination

12.6 Aggression

12.7 Prosocial Behavior

INTRODUCTION: Social psychologists examine how the presence of others impacts how a person behaves and reacts, whether that person is an athlete playing a game, a police officer on the job, or a worshiper attending a religious service. Social psychologists believe that a person’s behavior is influenced by who else is present in a given situation and the composition of social groups.

12.1 What is Social Psychology?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define social psychology

- Describe situational versus dispositional influences on behavior

- Describe the fundamental attribution error

- Explain actor-observer bias

- Describe self-serving bias

- Explain the just-world hypothesis

Social psychology examines how people affect one another, and it looks at the power of the situation. According to the American Psychological Association (n.d.), social psychologists “are interested in all aspects of personality and social interaction, exploring the influence of interpersonal and group relationships on human behavior.” Throughout this chapter, we will examine how the presence of other individuals and groups of people impacts a person’s behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. Essentially, people will change their behavior to align with the social situation at hand. If we are in a new situation or are unsure how to behave, we will take our cues from other individuals.

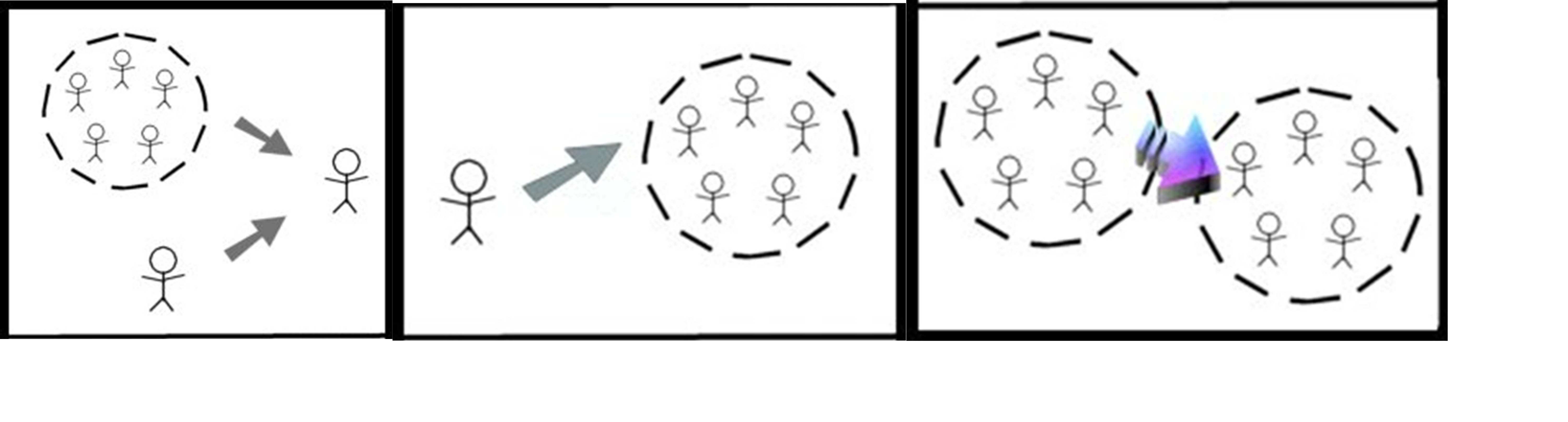

The field of social psychology studies topics at both the intra- and interpersonal levels. Intrapersonal topics (those that pertain to the individual) include emotions and attitudes, the self, and social cognition (the ways in which we think about ourselves and others). Interpersonal topics (those that pertain to dyads and groups) include helping behavior (Figure 12.2), aggression, prejudice and discrimination, attraction and close relationships, and group processes and intergroup relationships.

Situational and Dispositional Influences on Behavior

Behavior is a product of both the situation (e.g., cultural influences, social roles, and the presence of bystanders) and of the person (e.g., personality characteristics). Subfields of psychology tend to focus on one influence or behavior over others. Situationism is the view that our behavior and actions are determined by our immediate environment and surroundings. In contrast, dispositionism holds that our behavior is determined by internal factors (Heider, 1958). An internal factor is an attribute of a person and includes personality traits and temperament. Social psychologists have tended to take the situationist perspective, whereas personality psychologists have promoted the dispositionist perspective. Modern approaches to social psychology, however, take both the situation and the individual into account when studying human behavior (Fiske, Gilbert, & Lindzey, 2010). In fact, the field of social-personality psychology has emerged to study the complex interaction of internal and situational factors that affect human behavior (Mischel, 1977; Richard, Bond, & Stokes-Zoota, 2003).

Fundamental Attribution Error

In the United States, the predominant culture tends to favor a dispositional approach in explaining human behavior. Why do you think this is? We tend to think that people are in control of their own behaviors, and, therefore, any behavior change must be due to something internal, such as their personality, habits, or temperament. According to some social psychologists, people tend to overemphasize internal factors as explanations—or attributions—for the behavior of other people. They tend to assume that the behavior of another person is a trait of that person, and to underestimate the power of the situation on the behavior of others. They tend to fail to recognize when the behavior of another is due to situational variables, and thus to the person’s state. This erroneous assumption is called the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977; Riggio & Garcia, 2009). To better understand, imagine this scenario: Jamie returns home from work, and opens the front door to a happy greeting from spouse Morgan who inquires how the day has been. Instead of returning the spouse’s kind greeting, Jamie yells, “Leave me alone!” Why did Jamie yell? How would someone committing the fundamental attribution error explain Jamie’s behavior? The most common response is that Jamie is a mean, angry, or unfriendly person (traits). This is an internal or dispositional explanation. However, imagine that Jamie was just laid off from work due to company downsizing. Would your explanation for Jamie’s behavior change? Your revised explanation might be that Jamie was frustrated and disappointed about being laid off and was therefore in a bad mood (state). This is now an external or situational explanation for Jamie’s behavior.

The fundamental attribution error is so powerful that people often overlook obvious situational influences on behavior. A classic example was demonstrated in a series of experiments known as the quizmaster study (Ross, Amabile, & Steinmetz, 1977). Student participants were randomly assigned to play the role of a questioner (the quizmaster) or a contestant in a quiz game. Questioners developed difficult questions to which they knew the answers, and they presented these questions to the contestants. The contestants answered the questions correctly only 4 out of 10 times (Figure 12.3). After the task, the questioners and contestants were asked to rate their own general knowledge compared to the average student. Questioners did not rate their general knowledge higher than the contestants, but the contestants rated the questioners’ intelligence higher than their own. In a second study, observers of the interaction also rated the questioner as having more general knowledge than the contestant. The obvious influence on performance is the situation. The questioners wrote the questions, so of course they had an advantage. Both the contestants and observers made an internal attribution for the performance. They concluded that the questioners must be more intelligent than the contestants.

As demonstrated in the examples above, the fundamental attribution error is considered a powerful influence in how we explain the behaviors of others. However, it should be noted that some researchers have suggested that the fundamental attribution error may not be as powerful as it is often portrayed. In fact, a recent review of more than 173 published studies suggests that several factors (e.g., high levels of idiosyncrasy of the character and how well hypothetical events are explained) play a role in determining just how influential the fundamental attribution error is (Malle, 2006).

Is the Fundamental Attribution Error a Universal Phenomenon?

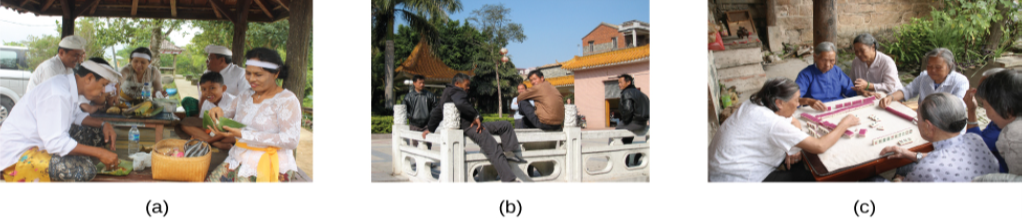

You may be able to think of examples of the fundamental attribution error in your life. Do people in all cultures commit the fundamental attribution error? Research suggests that they do not. People from an individualistic culture, that is, a culture that focuses on individual achievement and autonomy, have the greatest tendency to commit the fundamental attribution error. Individualistic cultures, which tend to be found in western countries such as the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, promote a focus on the individual. Therefore, a person’s disposition is thought to be the primary explanation for her behavior. In contrast, people from a collectivistic culture, that is, a culture that focuses on communal relationships with others, such as family, friends, and community (Figure 12.4), are less likely to commit the fundamental attribution error (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 2001).

| Characteristics of Individualistic and Collectivistic Cultures | |

|---|---|

| Individualistic Culture | Collectivistic Culture |

| Achievement oriented | Relationship oriented |

| Focus on autonomy | Focus on group harmony |

| Dispositional perspective | Situational perspective |

| Independent | Interdependent |

| Analytic thinking style | Holistic thinking style |

Masuda and Nisbett (2001) demonstrated that the kinds of information that people attend to when viewing visual stimuli (e.g., an aquarium scene) can differ significantly depending on whether the observer comes from a collectivistic versus an individualistic culture. Japanese participants were much more likely to recognize objects that were presented when they occurred in the same context in which they were originally viewed. Manipulating the context in which object recall occurred had no such impact on American participants. Other researchers have shown similar differences across cultures. For example, Zhang, Fung, Stanley, Isaacowitz, and Zhang (2014) demonstrated differences in the ways that holistic thinking might develop between Chinese and American participants, and Ramesh and Gelfand (2010) demonstrated that job turnover rates are more related to the fit between a person and the organization in which they work in an Indian sample, but the fit between the person and their specific job was more predictive of turnover in an American sample.

Actor-Observer Bias

Returning to our earlier example, Jamie was laid off, but an observer would not know. So a naïve observer would tend to attribute Jamie’s hostile behavior to Jamie’s disposition rather than to the true, situational cause. Why do you think we underestimate the influence of the situation on the behaviors of others? One reason is that we often don’t have all the information we need to make a situational explanation for another person’s behavior. The only information we might have is what is observable. Due to this lack of information we have a tendency to assume the behavior is due to a dispositional, or internal, factor. When it comes to explaining our own behaviors, however, we have much more information available to us. If you came home from school or work angry and yelled at your dog or a loved one, what would your explanation be? You might say you were very tired or feeling unwell and needed quiet time—a situational explanation. The actor-observer bias is the phenomenon of attributing other people’s behavior to internal factors (fundamental attribution error) while attributing our own behavior to situational forces (Jones & Nisbett, 1971; Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973; Choi & Nisbett, 1998). As actors of behavior, we have more information available to explain our own behavior. However as observers, we have less information available; therefore, we tend to default to a dispositionist perspective.

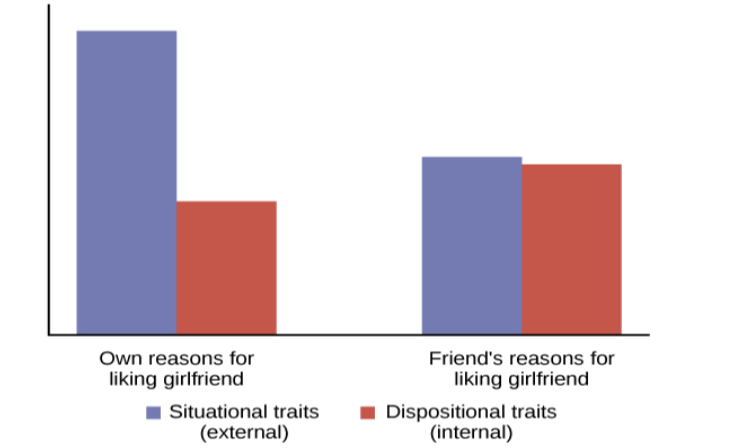

One study on the actor-observer bias investigated reasons male participants gave for why they liked their girlfriend (Nisbett et al., 1973). When asked why participants liked their own girlfriend, participants focused on internal, dispositional qualities of their girlfriends (for example, her pleasant personality). The participants’ explanations rarely included causes internal to themselves, such as dispositional traits (for example, “I need companionship.”). In contrast, when speculating why a male friend likes his girlfriend, participants were equally likely to give dispositional and external explanations. This supports the idea that actors tend to provide few internal explanations but many situational explanations for their own behavior. In contrast, observers tend to provide more dispositional explanations for a friend’s behavior (Figure 12.5).

Self-Serving Bias

We can understand self-serving bias by digging more deeply into attribution, a belief about the cause of a result. One model of attribution proposes three main dimensions: locus of control (internal versus external), stability (stable versus unstable), and controllability (controllable versus uncontrollable). In this context, stability refers the extent to which the circumstances that result in a given outcome are changeable. The circumstances are considered stable if they are unlikely to change. Controllability refers to the extent to which the circumstances that are associated with a given outcome can be controlled. Obviously, those things that we have the power to control would be labeled controllable (Weiner, 1979).

Following an outcome, self-serving biases are those attributions that enable us to see ourselves in a favorable light (for example, making internal attributions for success and external attributions for failures). When you do well at a task, for example acing an exam, it is in your best interest to make a dispositional attribution for your behavior (“I’m smart,”) instead of a situational one (“The exam was easy,”). The tendency of an individual to take credit by making dispositional or internal attributions for positive outcomes (Miller & Ross, 1975). Self-serving bias is the tendency to explain our successes as due to dispositional (internal) characteristics, but to explain our failures as due to situational (external) factors. Again, this is culture dependent. This bias serves to protect self-esteem. You can imagine that if people always made situational attributions for their behavior, they would never be able to take credit and feel good about their accomplishments.

Consider the example of how we explain our favorite sports team’s wins. Research shows that we make internal, stable, and controllable attributions for our team’s victory (Figure 12.6) (Grove, Hanrahan, & McInman, 1991). For example, we might tell ourselves that our team is talented (internal), consistently works hard (stable), and uses effective strategies (controllable). In contrast, we are more likely to make external, unstable, and uncontrollable attributions when our favorite team loses. For example, we might tell ourselves that the other team has more experienced players or that the referees were unfair (external), the other team played at home (unstable), and the cold weather affected our team’s performance (uncontrollable).

Just-World Hypothesis

One consequence of westerners’ tendency to provide dispositional explanations for behavior is victim blame (Jost & Major, 2001). When people experience bad fortune, others tend to assume that they somehow are responsible for their own fate. A common ideology, or worldview, in the United States is the just-world hypothesis. The just-world hypothesis is the belief that people get the outcomes they deserve (Lerner & Miller, 1978). In order to maintain the belief that the world is a fair place, people tend to think that good people experience positive outcomes, and bad people experience negative outcomes (Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004; Jost & Major, 2001). The ability to think of the world as a fair place, where people get what they deserve, allows us to feel that the world is predictable and that we have some control over our life outcomes (Jost et al., 2004; Jost & Major, 2001). For example, if you want to experience positive outcomes, you just need to work hard to get ahead in life.

Can you think of a negative consequence of the just-world hypothesis? One negative consequence is people’s tendency to blame poor individuals for their plight. What common explanations are given for why people live in poverty? Have you heard statements such as, “The poor are lazy and just don’t want to work” or “Poor people just want to live off the government”? What types of explanations are these, dispositional or situational? These dispositional explanations are clear examples of the fundamental attribution error. Blaming poor people for their poverty ignores situational factors that impact them, such as high unemployment rates, recession, poor educational opportunities, and the familial cycle of poverty (Figure 12.7). Other research shows that people who hold just-world beliefs have negative attitudes toward people who are unemployed and people living with AIDS (Sutton & Douglas, 2005). In the United States and other countries, victims of sexual assault may find themselves blamed for their abuse. Victim advocacy groups, such as Domestic Violence Ended (DOVE), attend court in support of victims to ensure that blame is directed at the perpetrators of sexual violence, not the victims.

12.1 TEST YOURSELF

12.2 Self-presentation

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe social roles and how they influence behavior

- Explain what social norms are and how they influence behavior

- Define script

- Describe the findings of Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment

As you’ve learned, social psychology is the study of how people affect one another’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We have discussed situational perspectives and social psychology’s emphasis on the ways in which a person’s environment, including culture and other social influences, affect behavior. In this section, we examine situational forces that have a strong influence on human behavior including social roles, social norms, and scripts. We discuss how humans use the social environment as a source of information, or cues, on how to behave. Situational influences on our behavior have important consequences, such as whether we will help a stranger in an emergency or how we would behave in an unfamiliar environment.

Social Roles

One major social determinant of human behavior is our social roles. A social role is a pattern of behavior that is expected of a person in a given setting or group (Hare, 2003). Each one of us has several social roles. You may be, at the same time, a student, a parent, an aspiring teacher, a son or daughter, a spouse, and a lifeguard. How do these social roles influence your behavior? Social roles are defined by culturally shared knowledge. That is, nearly everyone in a given culture knows what behavior is expected of a person in a given role. For example, what is the social role for a student? If you look around a college classroom you will likely see students engaging in studious behavior, taking notes, listening to the professor, reading the textbook, and sitting quietly at their desks (Figure 12.8). Of course you may see students deviating from the expected studious behavior such as texting on their phones or using Facebook on their laptops, but in all cases, the students that you observe are attending class—a part of the social role of students.

Social Norms

As discussed previously, social roles are defined by a culture’s shared knowledge of what is expected behavior of an individual in a specific role. This shared knowledge comes from social norms. A social norm is a group’s expectation of what is appropriate and acceptable behavior for its members—how they are supposed to behave and think (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955; Berkowitz, 2004). How are we expected to act? What are we expected to talk about? What are we expected to wear? In our discussion of social roles we noted that colleges have social norms for students’ behavior in the role of student and workplaces have social norms for employees’ behaviors in the role of employee. Social norms are everywhere including in families, gangs, and on social media outlets. What are some social norms on Facebook?

CONNECT THE CONCEPTS

Tweens, Teens, and Social Norms

My 11-year-old daughter, Janelle, recently told me she needed shorts and shirts for the summer, and that she wanted me to take her to a store at the mall that is popular with preteens and teens to buy them. I have noticed that many girls have clothes from that store, so I tried teasing her. I said, “All the shirts say ‘Aero’ on the front. If you are wearing a shirt like that and you have a substitute teacher, and the other girls are all wearing that type of shirt, won’t the substitute teacher think you are all named ‘Aero’?”

My daughter replied, in typical 11-year-old fashion, “Mom, you are not funny. Can we please go shopping?”

I tried a different tactic. I asked Janelle if having clothing from that particular store will make her popular. She replied, “No, it will not make me popular. It is what the popular kids wear. It will make me feel happier.” How can a label or name brand make someone feel happier? Think back to what you’ve learned about lifespan development. What is it about pre-teens and young teens that make them want to fit in (Figure 12.9)? Does this change over time? Think back to your high school experience, or look around your college campus. What is the main name brand clothing you see? What messages do we get from the media about how to fit in?

Scripts

Because of social roles, people tend to know what behavior is expected of them in specific, familiar settings. A script is a person’s knowledge about the sequence of events expected in a specific setting (Schank & Abelson, 1977). How do you act on the first day of school, when you walk into an elevator, or are at a restaurant? For example, at a restaurant in the United States, if we want the server’s attention, we try to make eye contact. In Brazil, you would make the sound “psst” to get the server’s attention. You can see the cultural differences in scripts. To an American, saying “psst” to a server might seem rude, yet to a Brazilian, trying to make eye contact might not seem an effective strategy. Scripts are important sources of information to guide behavior in given situations. Can you imagine being in an unfamiliar situation and not having a script for how to behave? This could be uncomfortable and confusing. How could you find out about social norms in an unfamiliar culture?

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment

The famous Stanford prison experiment, conducted by social psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues at Stanford University, demonstrated the power of social roles, social norms, and scripts. In the summer of 1971, an advertisement was placed in a California newspaper asking for male volunteers to participate in a study about the psychological effects of prison life. More than 70 men volunteered, and these volunteers then underwent psychological testing to eliminate candidates who had underlying psychiatric issues, medical issues, or a history of crime or drug abuse. The pool of volunteers was whittled down to 24 healthy male college students. Each student was paid $15 per day (equivalent to about $80 today) and was randomly assigned to play the role of either a prisoner or a guard in the study. Based on what you have learned about research methods, why is it important that participants were randomly assigned?

A mock prison was constructed in the basement of the psychology building at Stanford. Participants assigned to play the role of prisoners were “arrested” at their homes by Palo Alto police officers, booked at a police station, and subsequently taken to the mock prison. The experiment was scheduled to run for several weeks. To the surprise of the researchers, both the “prisoners” and “guards” assumed their roles with zeal. On the second day of the experiment, the guards forced the prisoners to strip, took their beds, and isolated the ringleaders using solitary confinement. In a relatively short time, the guards came to harass the prisoners in an increasingly sadistic manner, through a complete lack of privacy, lack of basic comforts such as mattresses to sleep on, and through degrading chores and late-night counts.

The prisoners, in turn, began to show signs of severe anxiety and hopelessness—they began tolerating the guards’ abuse. Even the Stanford professor who designed the study and was the head researcher, Philip Zimbardo, found himself acting as if the prison was real and his role, as prison supervisor, was real as well. After only six days, the experiment had to be ended due to the participants’ deteriorating behavior. Zimbardo explained,

At this point it became clear that we had to end the study. We had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation—a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically. Even the “good” guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work. (Zimbardo, 2013)

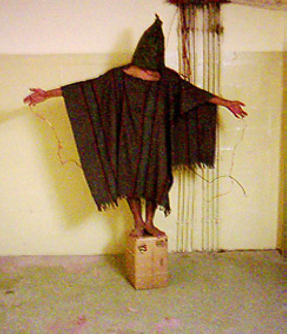

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been used as a memorable demonstration of the incredible power that social roles, norms, and scripts have in affecting human behavior. However, multiple aspects of the study have been subject to criticism since its inception. The nature of these criticisms range from ethical concerns to issues of generalizability (Bartels, Milovich, & Moussier, 2016; Griggs, 2014; Le Texier, 2019). One criticism is that the way students were recruited for the experiment may have impacted the outcome (Carnahan & McFarland, 2007). Another criticism questions the conclusions that can be drawn from the study. Zimbardo appears to have provided specific guidelines of the types of behaviors that were expected of the guards (Zimbardo, 2007). Subsequent research suggests that such guidelines likely created an expectation of the types of behavior that Zimbardo reported observing in the Stanford Prison Experiment (Bartels, 2019), and that given these expectations, the guards simply acted as they thought they were expected to act. It has also been problematic that attempts to replicate aspects of the study have not been successful. For example, when no guidelines were presented to the guards, researchers documented different outcomes than those observed by Zimbardo. (Reicher & Haslam, 2006). The Stanford Prison Experiment has some parallels with the abuse of prisoners of war by U.S. Army troops and CIA personnel at the Abu Ghraib prison in 2003 and 2004 during the Iraq War. The offenses at Abu Ghraib were documented by photographs of the abuse, some taken by the abusers themselves (Figure 12.10).

12.2 TEST YOURSELF

12.3 Attitudes and Persuasion

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define attitude

- Describe how people’s attitudes are internally changed through cognitive dissonance

- Explain how people’s attitudes are externally changed through persuasion

- Describe the peripheral and central routes to persuasion

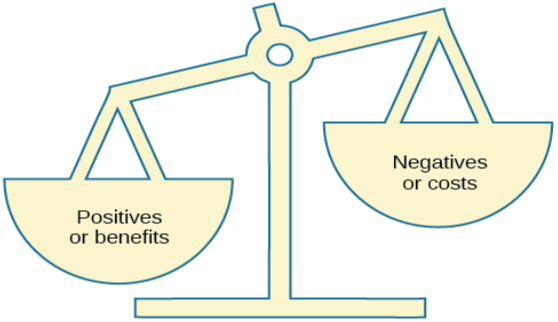

Social psychologists have documented how the power of the situation can influence our behaviors. Now we turn to how the power of the situation can influence our attitudes and beliefs. Attitude is our evaluation of a person, an idea, or an object. We have attitudes for many things ranging from products that we might pick up in the supermarket to people around the world to political policies. Typically, attitudes are favorable or unfavorable: positive or negative (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). And, they have three components: an affective component (feelings), a behavioral component (the effect of the attitude on behavior), and a cognitive component (belief and knowledge) (Rosenberg & Hovland, 1960).

For example, you may hold a positive attitude toward recycling. This attitude should result in positive feelings toward recycling (such as “It makes me feel good to recycle” or “I enjoy knowing that I make a small difference in reducing the amount of waste that ends up in landfills”). Certainly, this attitude should be reflected in our behavior: You actually recycle as often as you can. Finally, this attitude will be reflected in favorable thoughts (for example, “Recycling is good for the environment” or “Recycling is the responsible thing to do”).

Our attitudes and beliefs are not only influenced by external forces, but also by internal influences that we control. Like our behavior, our attitudes and thoughts are not always changed by situational pressures, but they can be consciously changed by our own free will. In this section we discuss the conditions under which we would want to change our own attitudes and beliefs.

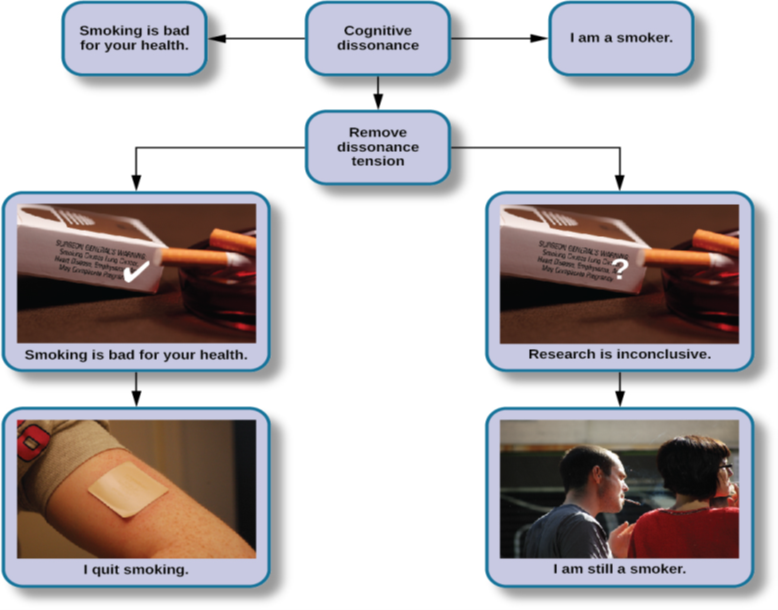

What is Cognitive Dissonance?

Social psychologists have documented that feeling good about ourselves and maintaining positive self-esteem is a powerful motivator of human behavior (Tavris & Aronson, 2008). In the United States, members of the predominant culture typically think very highly of themselves and view themselves as good people who are above average on many desirable traits (Ehrlinger, Gilovich, & Ross, 2005). Often, our behavior, attitudes, and beliefs are affected when we experience a threat to our self-esteem or positive self-image. Psychologist Leon Festinger (1957) defined cognitive dissonance as psychological discomfort arising from holding two or more inconsistent attitudes, behaviors, or cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, or opinions). Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance states that when we experience a conflict in our behaviors, attitudes, or beliefs that runs counter to our positive self-perceptions, we experience psychological discomfort (dissonance). For example, if you believe smoking is bad for your health but you continue to smoke, you experience conflict between your belief and behavior (Figure 12.11).

- changing our discrepant behavior (e.g., stop smoking),

- changing our cognitions through rationalization or denial (e.g., telling ourselves that health risks can be reduced by smoking filtered cigarettes),

- adding a new cognition (e.g., “Smoking suppresses my appetite so I don’t become overweight, which is good for my health.”).

A classic example of cognitive dissonance is Joaquin, a 20-year-old who enlists in the military. During boot camp he is awakened at 5:00 a.m., is chronically sleep deprived, yelled at, covered in sand flea bites, physically bruised and battered, and mentally exhausted (Figure 12.12). It gets worse. Recruits that make it to week 11 of boot camp have to do 54 hours of continuous training.

If Joaquin keeps thinking about how miserable he is, it is going to be a very long four years. He will be in a constant state of cognitive dissonance. As an alternative to this misery, Joaquin can change his beliefs or attitudes. He can tell himself, “I am becoming stronger, healthier, and sharper. I am learning discipline and how to defend myself and my country. What I am doing is really important.” If this is his belief, he will realize that he is becoming stronger through his challenges. He then will feel better and not experience cognitive dissonance, which is an uncomfortable state.

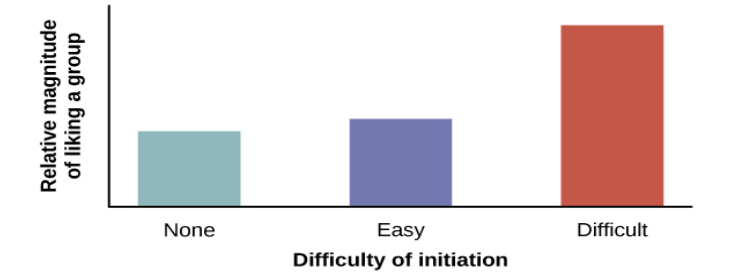

The Effect of Initiation

The military example demonstrates the observation that a difficult initiation into a group influences us to like the group more. Another social psychology concept, justification of effort, suggests that we value goals and achievements that we put a lot of effort into. According to this theory, if something is difficult for us to achieve, we believe it is more worthwhile. For example, if you move to an apartment and spend hours assembling a dresser you bought from Ikea, you will value that more than a fancier dresser your parents bought you. We do not want to have wasted time and effort to join a group that we eventually leave. A classic experiment by Aronson and Mills (1959) demonstrated this justification of effort effect. College students volunteered to join a campus group that would meet regularly to discuss the psychology of sex. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: no initiation, an easy initiation, and a difficult initiation into the group. After participating in the first discussion, which was deliberately made very boring, participants rated how much they liked the group. Participants who underwent a difficult initiation process to join the group rated the group more favorably than did participants with an easy initiation or no initiation (Figure 12.13).

Besides the classic military example and group initiation, can you think of other examples of cognitive dissonance? Here is one: Maria and Marco live in Fairfield County, Connecticut, which is one of the wealthiest areas in the United States and has a very high cost of living. Maria telecommutes from home and Marco does not work outside of the home. They rent a very small house for more than $3000 a month. Marco shops at consignment stores for clothes and economizes when possible. They complain that they never have any money and that they cannot buy anything new. When asked why they do not move to a less expensive location, since Maria telecommutes, they respond that Fairfield County is beautiful, they love the beaches, and they feel comfortable there. How does the theory of cognitive dissonance apply to Maria and Marco’s choices?

Persuasion

In the previous section, we discussed that the motivation to reduce cognitive dissonance leads us to change our attitudes, behaviors, and/or cognitions to make them consonant. Persuasion is the process of changing our attitude toward something based on some kind of communication. Much of the persuasion we experience comes from outside forces. How do people convince others to change their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Figure 12.14)? What communications do you receive that attempt to persuade you to change your attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors?

Yale Attitude Change Approach

The topic of persuasion has been one of the most extensively researched areas in social psychology (Fiske et al., 2010). During the Second World War, Carl Hovland extensively researched persuasion for the U.S. Army. After the war, Hovland continued his exploration of persuasion at Yale University. Out of this work came a model called the Yale attitude change approach, which describes the conditions under which people tend to change their attitudes. Hovland demonstrated that certain features of the source of a persuasive message, the content of the message, and the characteristics of the audience will influence the persuasiveness of a message (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953).

Features of the source of the persuasive message include the credibility of the speaker (Hovland & Weiss, 1951) and the physical attractiveness of the speaker (Eagly & Chaiken, 1975; Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997). Thus, speakers who are credible, or have expertise on the topic, and who are deemed as trustworthy are more persuasive than less credible speakers. Similarly, more attractive speakers are more persuasive than less attractive speakers. The use of famous actors and athletes to advertise products on television and in print relies on this principle. The immediate and long term impact of the persuasion also depends, however, on the credibility of the messenger (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Features of the message itself that affect persuasion include subtlety (the quality of being important, but not obvious) (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Walster & Festinger, 1962); sidedness (that is, having more than one side) (Crowley & Hoyer, 1994; Igou & Bless, 2003; Lumsdaine & Janis, 1953); timing (Haugtvedt & Wegener, 1994; Miller & Campbell, 1959), and whether both sides are presented. Messages that are more subtle are more persuasive than direct messages. Arguments that occur first, such as in a debate, are more influential if messages are given back-to-back. However, if there is a delay after the first message, and before the audience needs to make a decision, the last message presented will tend to be more persuasive (Miller & Campbell, 1959).

Features of the audience that affect persuasion are attention (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Festinger & Maccoby, 1964), intelligence, self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992), and age (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). In order to be persuaded, audience members must be paying attention. People with lower intelligence are more easily persuaded than people with higher intelligence; whereas people with moderate self-esteem are more easily persuaded than people with higher or lower self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992). Finally, younger adults aged 18–25 are more persuadable than older adults.

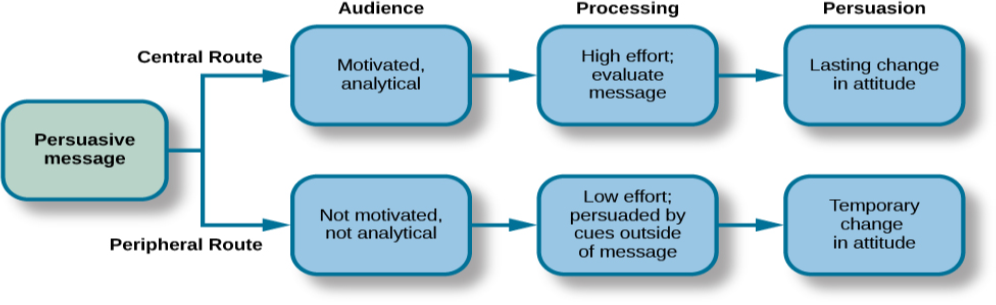

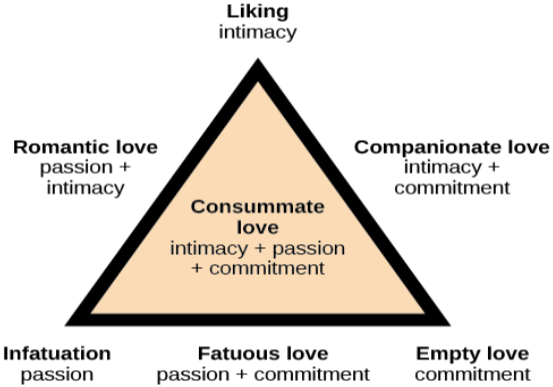

Elaboration Likelihood Model

An especially popular model that describes the dynamics of persuasion is the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The elaboration likelihood model considers the variables of the attitude change approach—that is, features of the source of the persuasive message, contents of the message, and characteristics of the audience are used to determine when attitude change will occur. According to the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion, there are two main routes that play a role in delivering a persuasive message: central and peripheral (Figure 12.15).

The central route to persuasion works best when the target of persuasion, or the audience, is analytical and willing to engage in processing of the information. From an advertiser’s perspective, what products would be best sold using the central route to persuasion? What audience would most likely be influenced to buy the product? One example is buying a computer. It is likely, for example, that small business owners might be especially influenced by the focus on the computer’s quality and features such as processing speed and memory capacity.

The peripheral route is an indirect route that uses peripheral cues to associate positivity with the message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Instead of focusing on the facts and a product’s quality, the peripheral route relies on association with positive characteristics such as positive emotions and celebrity endorsement. For example, having a popular athlete advertise athletic shoes is a common method used to encourage young adults to purchase the shoes. This route to attitude change does not require much effort or information processing. This method of persuasion may promote positivity toward the message or product, but it typically results in less permanent attitude or behavior change. The audience does not need to be analytical or motivated to process the message. In fact, a peripheral route to persuasion may not even be noticed by the audience, for example in the strategy of product placement. Product placement refers to putting a product with a clear brand name or brand identity in a TV show or movie to promote the product (Gupta & Lord, 1998). For example, one season of the reality series American Idol prominently showed the panel of judges drinking out of cups that displayed the Coca-Cola logo. What other products would be best sold using the peripheral route to persuasion? Another example is clothing: A retailer may focus on celebrities that are wearing the same style of clothing.

Foot-in-the-door Technique

Researchers have tested many persuasion strategies that are effective in selling products and changing people’s attitude, ideas, and behaviors. One effective strategy is the foot-in-the-door technique (Cialdini, 2001; Pliner, Hart, Kohl, & Saari, 1974). Using the foot-in-the-door technique, the persuader gets a person to agree to bestow a small favor or to buy a small item, only to later request a larger favor or purchase of a bigger item. The foot-in-the-door technique was demonstrated in a study by Freedman and Fraser (1966) in which participants who agreed to post small sign in their yard or sign a petition were more likely to agree to put a large sign in their yard than people who declined the first request (Figure 12.16). Research on this technique also illustrates the principle of consistency (Cialdini, 2001): Our past behavior often directs our future behavior, and we have a desire to maintain consistency once we have a committed to a behavior.

How would a store owner use the foot-in-the-door technique to sell you an expensive product? For example, say that you are buying the latest model smartphone, and the salesperson suggests you purchase the best data plan. You agree to this. The salesperson then suggests a bigger purchase—the three-year extended warranty. After agreeing to the smaller request, you are more likely to also agree to the larger request. You may have encountered this if you have bought a car. When salespeople realize that a buyer intends to purchase a certain model, they might try to get the customer to pay for many or most available options on the car. Another example of the foot-in-the-door technique would be applied to an individual in the market for a used car who decides to buy a fully loaded new car. Why? Because the salesperson convinced the buyer that they need a car that has all of the safety features that were not available in the used car.

12.3 TEST YOURSELF

12.4 Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the Asch effect

- Define conformity and types of social influence

- Describe Stanley Milgram’s experiment and its implications

- Define groupthink, social facilitation, and social loafing

In this section, we discuss additional ways in which people influence others. The topics of conformity, social influence, obedience, and group processes demonstrate the power of the social situation to change our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We begin this section with a discussion of a famous social psychology experiment that demonstrated how susceptible humans are to outside social pressures.

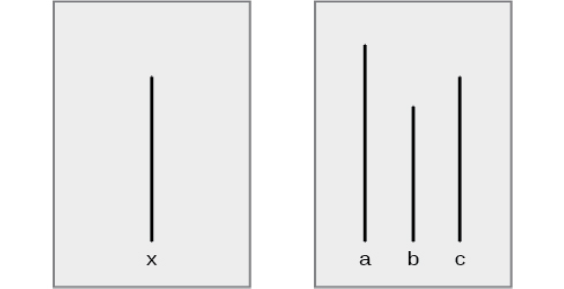

Conformity

Solomon Asch conducted several experiments in the 1950s to determine how people are affected by the thoughts and behaviors of other people. In one study, a group of participants was shown a series of printed line segments of different lengths: a, b, and c (Figure 12.17). Participants were then shown a fourth line segment: x. They were asked to identify which line segment from the first group (a, b, or c) most closely resembled the fourth line segment in length.

Each group of participants had only one true, naïve subject. The remaining members of the group were confederates of the researcher. A confederate is a person who is aware of the experiment and works for the researcher. Confederates are used to manipulate social situations as part of the research design, and the true, naïve participants believe that confederates are, like them, uninformed participants in the experiment. In Asch’s study, the confederates identified a line segment that was obviously shorter than the target line—a wrong answer. The naïve participant then had to identify aloud the line segment that best matched the target line segment.

How often do you think the true participant aligned with the confederates’ response? That is, how often do you think the group influenced the participant, and the participant gave the wrong answer? Asch (1955) found that 76% of participants conformed to group pressure at least once by indicating the incorrect line. Conformity is the change in a person’s behavior to go along with the group, even if he does not agree with the group. Why would people give the wrong answer? What factors would increase or decrease someone giving in or conforming to group pressure?

The Asch effect is the influence of the group majority on an individual’s judgment.

What factors make a person more likely to yield to group pressure? Research shows that the size of the majority, the presence of another dissenter, and the public or relatively private nature of responses are key influences on conformity.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity. In Asch’s study, conformity increased with the number of people in the majority—up to seven individuals. At numbers beyond seven, conformity leveled off and decreased slightly (Asch, 1955).

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero (Asch, 1955).

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The finding that conformity is more likely to occur when responses are public than when they are private is the reason government elections require voting in secret, so we are not coerced by others (Figure 12.18). The Asch effect can be easily seen in children when they have to publicly vote for something. For example, if the teacher asks whether the children would rather have extra recess, no homework, or candy, once a few children vote, the rest will comply and go with the majority. In a different classroom, the majority might vote differently, and most of the children would comply with that majority. When someone’s vote changes if it is made in public versus private, this is known as compliance. Compliance can be a form of conformity. Compliance is going along with a request or demand, even if you do not agree with the request. In Asch’s studies, the participants complied by giving the wrong answers, but privately did not accept that the obvious wrong answers were correct.

In normative social influence, people conform to the group norm to fit in, to feel good, and to be accepted by the group. However, with informational social influence, people conform because they believe the group is competent and has the correct information, particularly when the task or situation is ambiguous. What type of social influence was operating in the Asch conformity studies? Since the line judgment task was unambiguous, participants did not need to rely on the group for information. Instead, participants complied to fit in and avoid ridicule, an instance of normative social influence.

An example of informational social influence may be what to do in an emergency situation. Imagine that you are in a movie theater watching a film and what seems to be smoke comes in the theater from under the emergency exit door. You are not certain that it is smoke—it might be a special effect for the movie, such as a fog machine. When you are uncertain you will tend to look at the behavior of others in the theater. If other people show concern and get up to leave, you are likely to do the same. However, if others seem unconcerned, you are likely to stay put and continue watching the movie (Figure 12.19).

Stanley Milgram’s Experiment

Conformity is one effect of the influence of others on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Another form of social influence is obedience to authority. Obedience is the change of an individual’s behavior to comply with a demand by an authority figure. People often comply with the request because they are concerned about a consequence if they do not comply. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we review another classic social psychology experiment.

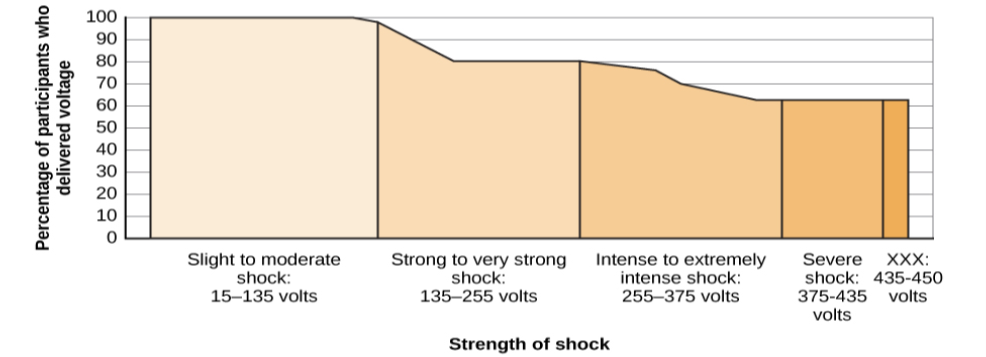

Stanley Milgram was a social psychology professor at Yale who was influenced by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. Eichmann’s defense for the atrocities he committed was that he was “just following orders.” Milgram (1963) wanted to test the validity of this defense, so he designed an experiment and initially recruited 40 men for his experiment. The volunteer participants were led to believe that they were participating in a study to improve learning and memory. The participants were told that they were to teach other students (learners) correct answers to a series of test items. The participants were shown how to use a device that they were told delivered electric shocks of different intensities to the learners. The participants were told to shock the learners if they gave a wrong answer to a test item—that the shock would help them to learn. The participants believed they gave the learners shocks, which increased in 15-volt increments, all the way up to 450 volts. The participants did not know that the learners were confederates and that the confederates did not actually receive shocks.

In response to a string of incorrect answers from the learners, the participants obediently and repeatedly shocked them. The confederate learners cried out for help, begged the participant teachers to stop, and even complained of heart trouble. Yet, when the researcher told the participant-teachers to continue the shock, 65% of the participants continued the shock to the maximum voltage and to the point that the learner became unresponsive (Figure 12.20). What makes someone obey authority to the point of potentially causing serious harm to another person?

This case is still very applicable today. What does a person do if an authority figure orders something done? What if the person believes it is incorrect, or worse, unethical? In a study by Martin and Bull (2008), midwives privately filled out a questionnaire regarding best practices and expectations in delivering a baby. Then, a more senior midwife and supervisor asked the junior midwives to do something they had previously stated they were opposed to. Most of the junior midwives were obedient to authority, going against their own beliefs. Burger (2009) partially replicated this study. He found among a multicultural sample of women and men that their levels of obedience matched Milgram’s research. Doliński et al. (2017) performed a replication of Burger’s work in Poland and controlled for the gender of both participants and learners, and once again, results that were consistent with Milgram’s original work were observed.

Groupthink

When in group settings, we are often influenced by the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of people around us. Whether it is due to normative or informational social influence, groups have power to influence individuals. Another phenomenon of group conformity is groupthink. Groupthink is the modification of the opinions of members of a group to align with what they believe is the group consensus (Janis, 1972). In group situations, the group often takes action that individuals would not perform outside the group setting because groups make more extreme decisions than individuals do. Moreover, groupthink can hinder opposing trains of thought. This elimination of diverse opinions contributes to faulty decision by the group.

DIG DEEPER

Groupthink in the U.S. Government

There have been several instances of groupthink in the U.S. government. One example occurred when the United States led a small coalition of nations to invade Iraq in March 2003. This invasion occurred because a small group of advisors and former President George W. Bush were convinced that Iraq represented a significant terrorism threat with a large stockpile of weapons of mass destruction at its disposal. Although some of these individuals may have had some doubts about the credibility of the information available to them at the time, in the end, the group arrived at a consensus that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and represented a significant threat to national security. It later came to light that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction, but not until the invasion was well underway. As a result, 6000 American soldiers were killed and many more civilians died. How did the Bush administration arrive at their conclusions? View this video of Colin Powell, 10 years after his famous United Nations speech, discussing the information he had at the time that his decisions were based on. (“CNN Official Interview: Colin Powell now regrets UN speech about WMDs,” 2010).

Do you see evidence of groupthink?

Why does groupthink occur? There are several causes of groupthink, which makes it preventable. When the group is highly cohesive, or has a strong sense of connection, maintaining group harmony may become more important to the group than making sound decisions. If the group leader is directive and makes his opinions known, this may discourage group members from disagreeing with the leader. If the group is isolated from hearing alternative or new viewpoints, groupthink may be more likely. How do you know when groupthink is occurring?

There are several symptoms of groupthink including the following:

- perceiving the group as invulnerable or invincible—believing it can do no wrong

- believing the group is morally correct

- self-censorship by group members, such as withholding information to avoid disrupting the group consensus

- the quashing of dissenting group members’ opinions

- the shielding of the group leader from dissenting views

- perceiving an illusion of unanimity among group members

- holding stereotypes or negative attitudes toward the out-group or others’ with differing viewpoints (Janis, 1972)

Given the causes and symptoms of groupthink, how can it be avoided? There are several strategies that can improve group decision making including seeking outside opinions, voting in private, having the leader withhold position statements until all group members have voiced their views, conducting research on all viewpoints, weighing the costs and benefits of all options, and developing a contingency plan (Janis, 1972; Mitchell & Eckstein, 2009).

Group Polarization

Another phenomenon that occurs within group settings is group polarization. Group polarization (Teger & Pruitt, 1967) is the strengthening of an original group attitude after the discussion of views within a group. That is, if a group initially favors a viewpoint, after discussion the group consensus is likely a stronger endorsement of the viewpoint. Conversely, if the group was initially opposed to a viewpoint, group discussion would likely lead to stronger opposition. Group polarization explains many actions taken by groups that would not be undertaken by individuals. Group polarization can be observed at political conventions, when platforms of the party are supported by individuals who, when not in a group, would decline to support them. Recently, some theorists have argued that group polarization may be partly responsible for the extreme political partisanship that seems ubiquitous in modern society. Given that people can self-select media outlets that are most consistent with their own political views, they are less likely to encounter opposing viewpoints. Over time, this leads to a strengthening of their own perspective and of hostile attitudes and behaviors towards those with different political ideals. Remarkably, political polarization leads to open levels of discrimination that are on par with, or perhaps exceed, racial discrimination (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015). A more everyday example is a group’s discussion of how attractive someone is. Does your opinion change if you find someone attractive, but your friends do not agree? If your friends vociferously agree, might you then find this person even more attractive?

Social traps refer to situations that arise when individuals or groups of individuals behave in ways that are not in their best interest and that may have negative, long-term consequences. However, once established, a social trap is very difficult to escape. For example, following World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. While the presence of nuclear weapons is not in either party’s best interest, once the arms race began, each country felt the need to continue producing nuclear weapons to protect itself from the other.

Social Loafing

Imagine you were just assigned a group project with other students whom you barely know. Everyone in your group will get the same grade. Are you the type who will do most of the work, even though the final grade will be shared? Or are you more likely to do less work because you know others will pick up the slack? Social loafing involves a reduction in individual output on tasks where contributions are pooled. Because each individual’s efforts are not evaluated, individuals can become less motivated to perform well. Karau and Williams (1993) and Simms and Nichols (2014) reviewed the research on social loafing and discerned when it was least likely to happen. The researchers noted that social loafing could be alleviated if, among other situations, individuals knew their work would be assessed by a manager (in a workplace setting) or instructor (in a classroom setting), or if a manager or instructor required group members to complete self-evaluations.

The likelihood of social loafing in student work groups increases as the size of the group increases (Shepperd & Taylor, 1999). According to Kamau and Williams (1993), college students were the population most likely to engage in social loafing. Their study also found that women and participants from collectivistic cultures were less likely to engage in social loafing, explaining that their group orientation may account for this.

College students could work around social loafing or “free-riding” by suggesting to their professors use of a flocking method to form groups. Harding (2018) compared groups of students who had self-selected into groups for class to those who had been formed by flocking, which involves assigning students to groups who have similar schedules and motivations. Not only did she find that students reported less “free riding,” but that they also did better in the group assignments compared to those whose groups were self-selected.

Interestingly, the opposite of social loafing occurs when the task is complex and difficult (Bond & Titus, 1983; Geen, 1989). In a group setting, such as the student work group, if your individual performance cannot be evaluated, there is less pressure for you to do well, and thus less anxiety or physiological arousal (Latané, Williams, & Harkens, 1979). This puts you in a relaxed state in which you can perform your best, if you choose (Zajonc, 1965). If the task is a difficult one, many people feel motivated and believe that their group needs their input to do well on a challenging project (Jackson & Williams, 1985).

Deindividuation

Another way that being part of a group can affect behavior is exhibited in instances in which deindividuation occurs. Deindividuation refers to situations in which a person may feel a sense of anonymity and therefore a reduction in accountability and sense of self when among others. Deindividuation is often pointed to in cases in which mob or riot-like behaviors occur (Zimbardo, 1969), but research on the subject and the role that deindividuation plays in such behaviors has resulted in inconsistent results (as discussed in Granström, Guvå, Hylander, & Rosander, 2009).

Table 12.2 summarizes the types of social influence you have learned about in this chapter.

| Types of Social Influence | |

|---|---|

| Type of Social Influence | Description |

| Conformity | Changing your behavior to go along with the group even if you do not agree with the group |

| Compliance | Going along with a request or demand |

| Normative social influence | Conformity to a group norm to fit in, feel good, and be accepted by the group |

| Informational social influence | Conformity to a group norm prompted by the belief that the group is competent and has the correct information |

| Obedience | Changing your behavior to please an authority figure or to avoid aversive consequences |

| Groupthink | Tendency to prioritize group cohesion over critical thinking that might lead to poor decision making; more likely to occur when there is perceived unanimity among the group |

| Group polarization | Strengthening of the original group attitude after discussing views within a group |

| Social facilitation | Improved performance when an audience is watching versus when the individual performs the behavior alone |

| Social loafing | Exertion of less effort by a person working in a group because individual performance cannot be evaluated separately from the group, thus causing performance decline on easy tasks |

| Deindividuation | Group situation in which a person may feel a sense of anonymity and a resulting reduction in accountability and sense of self |

12.4 TEST YOURSELF

12.5 Prejudice and Discrimination

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and distinguish among prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination

- Provide examples of prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination

- Explain why prejudice and discrimination exist

Human conflict can result in crime, war, and mass murder, such as genocide. Prejudice and discrimination often are root causes of human conflict, which explains how strangers come to hate one another to the extreme of causing others harm. Prejudice and discrimination affect everyone. In this section we will examine the definitions of prejudice and discrimination, examples of these concepts, and causes of these biases.

Understanding Prejudice and Discrimination

Humans are very diverse and although we share many similarities, we also have many differences. The social groups we belong to help form our identities (Tajfel, 1974). These differences may be difficult for some people to reconcile, which may lead to prejudice toward people who are different. Prejudice is a negative attitude and feeling toward an individual based solely on one’s membership in a particular social group (Allport, 1954; Brown, 2010). Prejudice is common against people who are members of an unfamiliar cultural group. Thus, certain types of education, contact, interactions, and building relationships with members of different cultural groups can reduce the tendency toward prejudice. In fact, simply imagining interacting with members of different cultural groups might affect prejudice. Indeed, when experimental participants were asked to imagine themselves positively interacting with someone from a different group, this led to an increased positive attitude toward the other group and an increase in positive traits associated with the other group. Furthermore, imagined social interaction can reduce anxiety associated with inter-group interactions (Crisp & Turner, 2009). What are some examples of social groups that you belong to that contribute to your identity? Social groups can include gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, social class, religion, sexual orientation, profession, and many more. And, as is true for social roles, you can simultaneously be a member of more than one social group. An example of prejudice is having a negative attitude toward people who are not born in the United States. Although people holding this prejudiced attitude do not know all people who were not born in the United States, they dislike them due to their status as foreigners.

Can you think of a prejudiced attitude you have held toward a group of people? How did your prejudice develop? Prejudice often begins in the form of a stereotype—that is, a specific belief or assumption about individuals based solely on their membership in a group, regardless of their individual characteristics. Stereotypes become overgeneralized and applied to all members of a group. For example, someone holding prejudiced attitudes toward older adults, may believe that older adults are slow and incompetent (Cuddy, Norton, & Fiske, 2005; Nelson, 2004). We cannot possibly know each individual person of advanced age to know that all older adults are slow and incompetent. Therefore, this negative belief is overgeneralized to all members of the group, even though many of the individual group members may, in fact, be spry and intelligent.

Another example of a well-known stereotype involves beliefs about racial differences among athletes. As Hodge, Burden, Robinson, and Bennett (2008) point out, Black male athletes are often believed to be more athletic, yet less intelligent, than their White male counterparts. These beliefs persist despite a number of high profile examples to the contrary. Sadly, such beliefs often influence how these athletes are treated by others and how they view themselves and their own capabilities. Whether or not you agree with a stereotype, stereotypes are generally well-known within a given culture (Devine, 1989).

Sometimes people will act on their prejudiced attitudes toward a group of people, and this behavior is known as discrimination. Discrimination is negative action toward an individual as a result of one’s membership in a particular group (Allport, 1954; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). As a result of holding negative beliefs (stereotypes) and negative attitudes (prejudice) about a particular group, people often treat the target of prejudice poorly, such as excluding older adults from their circle of friends. An example of a psychologist experiencing gender discrimination is found in the life and studies of Mary Whiton Calkins. Calkins was given special permission to attend graduate seminars at Harvard (at that time in the late 1880s, Harvard did not accept women) and at one point was the sole student of the famous psychologist William James. She passed all the requirements needed for a PhD and was described by psychologist Hugo Münsterberg as “one of the strongest professors of psychology in this country.” However, Harvard refused to grant Calkins a PhD because she was a woman (Harvard University, 2019). Table 12.3 summarizes the characteristics of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Have you ever been the target of discrimination? If so, how did this negative treatment make you feel?

| Connecting Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Function | Connection | Example |

| Stereotype | Cognitive; thoughts about people | Overgeneralized beliefs about people may lead to prejudice. | “Yankees fans are arrogant and obnoxious.” |

| Prejudice | Affective; feelings about people, both positive and negative | Feelings may influence treatment of others, leading to discrimination. | “I hate Yankees fans; they make me angry.” |

| Discrimination | Behavior; positive or negative treatment of others | Holding stereotypes and harboring prejudice may lead to excluding, avoiding, and biased treatment of group members. | “I would never hire nor become friends with a person if I knew he or she were a Yankees fan.” |

So far, we’ve discussed stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination as negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors because these are typically the most problematic. However, it is important to also point out that people can hold positive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward individuals based on group membership; for example, they would show preferential treatment for people who are like themselves—that is, who share the same gender, race, or favorite sports team.

Types of Prejudice and Discrimination

When we meet strangers we automatically process three pieces of information about them: their race, gender, and age (Ito & Urland, 2003). Why are these aspects of an unfamiliar person so important? Why don’t we instead notice whether their eyes are friendly, whether they are smiling, their height, the type of clothes they are wearing? Although these secondary characteristics are important in forming a first impression of a stranger, the social categories of race, gender, and age provide a wealth of information about an individual. This information, however, often is based on stereotypes. We may have different expectations of strangers depending on their race, gender, and age. What stereotypes and prejudices do you hold about people who are from a race, gender, and age group different from your own?

Racism

Racism is prejudice and discrimination against an individual based solely on one’s membership in a specific racial group (such as toward African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, European Americans). What are some stereotypes of various racial or ethnic groups? Research suggests cultural stereotypes for Asian Americans include cold, sly, and intelligent; for Latinos, cold and unintelligent; for European Americans, cold and intelligent; and for African Americans, aggressive, athletic, and more likely to be law breakers (Devine & Elliot, 1995; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Sommers & Ellsworth, 2000; Dixon & Linz, 2000).

Racism exists for many racial and ethnic groups. For example, Blacks are significantly more likely to have their vehicles searched during traffic stops than Whites, particularly when Blacks are driving in predominately White neighborhoods, a phenomenon often termed “DWB” or “driving while Black” (Rojek, Rosenfeld, & Decker, 2012).

Mexican Americans and other Latino groups also are targets of racism from the police and other members of the community. For example, when purchasing items with a personal check, Latino shoppers are more likely than White shoppers to be asked to show formal identification (Dovidio et al., 2010).

In one case of alleged harassment by the police, several East Haven, Connecticut, police officers were arrested on federal charges due to reportedly continued harassment and brutalization of Latinos. When the accusations came out, the mayor of East Haven was asked, “What are you doing for the Latino community today?” The Mayor responded, “I might have tacos when I go home, I’m not quite sure yet” (“East Haven Mayor,” 2012). This statement undermines the important issue of racial profiling and police harassment of Latinos, while belittling Latino culture by emphasizing an interest in a food product stereotypically associated with Latinos.

Racism is prevalent toward many other groups in the United States including Native Americans, Arab Americans, Jewish Americans, and Asian Americans. Have you experienced or witnessed racism toward any of these racial or ethnic groups? Are you aware of racism in your community?

One reason modern forms of racism, and prejudice in general, are hard to detect is related to the dual attitudes model (Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). Humans have two forms of attitudes: explicit attitudes, which are conscious and controllable, and implicit attitudes, which are unconscious and uncontrollable (Devine, 1989; Olson & Fazio, 2003). Because holding egalitarian views is socially desirable (Plant & Devine, 1998), most people do not show extreme racial bias or other prejudices on measures of their explicit attitudes. However, measures of implicit attitudes often show evidence of mild to strong racial bias or other prejudices (Greenwald, McGee, & Schwartz, 1998; Olson & Fazio, 2003).

Sexism

Sexism is prejudice and discrimination toward individuals based on their sex. Typically, sexism takes the form of men holding biases against women, but either sex can show sexism toward their own or their opposite sex. Like racism, sexism may be subtle and difficult to detect. Common forms of sexism in modern society include gender role expectations, such as expecting women to be the caretakers of the household. Sexism also includes people’s expectations for how members of a gender group should behave. For example, women are expected to be friendly, passive, and nurturing, and when women behave in an unfriendly, assertive, or neglectful manner they often are disliked for violating their gender role (Rudman, 1998). Research by Laurie Rudman (1998) finds that when female job applicants self-promote, they are likely to be viewed as competent, but they may be disliked and are less likely to be hired because they violated gender expectations for modesty. Sexism can exist on a societal level such as in hiring, employment opportunities, and education. Women are less likely to be hired or promoted in male-dominated professions such as engineering, aviation, and construction (Figure 12.22) (Blau, Ferber, & Winkler, 2010; Ceci & Williams, 2011). Have you ever experienced or witnessed sexism? Think about your family members’ jobs or careers. Why do you think there are differences in the jobs women and men have, such as more women nurses but more male surgeons (Betz, 2008)?

People often form judgments and hold expectations about people based on their age. These judgments and expectations can lead to ageism, or prejudice and discrimination toward individuals based solely on their age. Think of expectations you hold for older adults. How could someone’s expectations influence the feelings they hold toward individuals from older age groups? Ageism is widespread in U.S. culture (Nosek, 2005), and a common ageist attitude toward older adults is that they are incompetent, physically weak, and slow (Greenberg, Schimel, & Martens, 2002) and some people consider older adults less attractive. Chang, Kannoth, Levy, Wang, Lee, and Levy (2020) reported on relationships between ageism and health outcomes over a 40-year-plus period from countries around the world. Across 11 health domains, people over 50 were likely to experience ageism most often in the form of being denied access to health services and work opportunities. Some cultures, however, including some Asian, Latino, and African American cultures, both outside and within the United States afford older adults respect and honor.

Typically, ageism occurs against older adults, but ageism also can occur toward younger adults. What expectations do you hold toward younger people? Does society expect younger adults to be immature and irresponsible? Raymer, Reed, Spiegel, and Purvanova (2017) examined ageism against younger workers. They found that older workers endorsed negative stereotypes of younger workers, believing that they had more work deficit characteristics (including perceptions of incompetence). How might these forms of ageism affect a younger and older adult who are applying for a sales clerk position?

Homophobia

Another form of prejudice is homophobia: an umbrella term referring to prejudice and discrimination of individuals based solely on their sexual orientation, which is often applied to bisexual, lesbian, gay, and other non-heterosexual people. Transphobia is the hatred or fear of those who are perceived to break or blur stereotypical gender roles, often expressed as stereotyping, discrimination, harassment and/or violence. Like ageism, homophobia is a widespread prejudice in U.S. society that is tolerated by many people (Herek & McLemore, 2013; Nosek, 2005). Negative feelings often result in discrimination, such as the exclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) people from social groups and the avoidance of LGBTQ+ neighbors and co-workers. This discrimination also extends to employers deliberately declining to hire qualified LGBTQ+ job applicants, a practice officially outlawed by a 2020 Surpreme Court decision but which remains a significant issue. Have you experienced or witnessed homophobia? If so, what stereotypes, prejudiced attitudes, and discrimination were evident?

DIG DEEPER

Research into Homophobia

Some people are quite passionate in their hatred for nonheterosexuals in our society. In some cases, people have been tortured and/or murdered simply because they were not straight. This passionate response has led some researchers to question what motives might exist for homophobic people. Adams, Wright, & Lohr (1996) conducted a study investigating this issue and their results were quite an eye-opener.

In this experiment, male college students were given a scale that assessed how homophobic they were; those with extreme scores were recruited to participate in the experiment. In the end, 64 men agreed to participate and were split into 2 groups: homophobic men and nonhomophobic men. Both groups of men were fitted with a penile plethysmograph, an instrument that measures changes in blood flow to the penis and serves as an objective measurement of sexual arousal.

All men were shown segments of sexually explicit videos. One of these videos involved a sexual interaction between a man and a woman (straight clip). One video displayed two females engaged in a sexual interaction (lesbian clip), and the final video displayed two men engaged in a sexual interaction (gay clip). Changes in penile tumescence (a measure of physiological genital arousal) were recorded during all three clips, and a subjective measurement of sexual arousal was also obtained. While both groups of men became sexually aroused to the straight and lesbian video clips, only those men who were identified as homophobic showed sexual arousal to the gay male video clip. While all men reported that their erections indicated arousal for the straight and lesbian clips, the homophobic men indicated that they were not sexually aroused (despite their erections) to the gay clips. Adams et al. (1996) suggest that these findings may indicate that homophobia is related to gay arousal that the homophobic individuals either deny or are unaware.

Why Do Prejudice and Discrimination Exist?

Prejudice and discrimination persist in society due to social learning and conformity to social norms. Children learn prejudiced attitudes and beliefs from society: their parents, teachers, friends, the media, and other sources of socialization, such as Facebook (O’Keeffe & Clarke-Pearson, 2011). If certain types of prejudice and discrimination are acceptable in a society, there may be normative pressures to conform and share those prejudiced beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. For example, public and private schools are still somewhat segregated by social class. Historically, only children from wealthy families could afford to attend private schools, whereas children from middle- and low-income families typically attended public schools. If a child from a low-income family received a merit scholarship to attend a private school, how might the child be treated by classmates? Can you recall a time when you held prejudiced attitudes or beliefs or acted in a discriminatory manner because your group of friends expected you to?

Stereotypes and Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

When we hold a stereotype about a person, we have expectations that he or she will fulfill that stereotype. A self-fulfilling prophecy is an expectation held by a person that alters his or her behavior in a way that tends to make it true. When we hold stereotypes about a person, we tend to treat the person according to our expectations. This treatment can influence the person to act according to our stereotypic expectations, thus confirming our stereotypic beliefs. Research by Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) found that disadvantaged students whose teachers expected them to perform well had higher grades than disadvantaged students whose teachers expected them to do poorly.