Christopher Brooks

The End of the Republic

The Roman Republic lasted for roughly five centuries. It was under the Republic that Rome evolved from a single town to the heart of an enormous empire. Despite the evident success of the republican system, however, there were inexorable problems that plagued the Republic throughout its history, most evidently the problem of wealth and power. Roman citizens were, by law, supposed to have a stake in the Republic. They took pride in who they were and it was the common patriotic desire to fight and expand the Republic among the citizen-soldiers of the Republic that created, at least in part, such an effective army. At the same time, the vast amount of wealth captured in the military campaigns was frequently siphoned off by elites, who found ways to seize large portions of land and loot with each campaign. By around 100 BCE even the existence of the Plebeian Assembly did almost nothing to mitigate the effect of the debt and poverty that afflicted so many Romans thanks to the power of the clientage networks overseen by powerful noble patrons.

The key factor behind the political stability of the Republic up until the aftermath of the Punic Wars was that there had never been open fighting between elite Romans in the name of political power. In a sense, Roman expansion (and especially the brutal wars against Carthage) had united the Romans; despite their constant political battles within the assemblies and the senate, it had never come to actual bloodshed. Likewise, a very strong component of Romanitas was the idea that political arguments were to be settled with debate and votes, not clubs and knives. Both that unity and that emphasis on peaceful conflict resolution within the Roman state itself began to crumble after the sack of Carthage.

The first step toward violent revolution in the Republic was the work of the Gracchus brothers – remembered historically as the Gracchi (i.e. “Gracchi” is the plural of “Gracchus”). The older of the two was Tiberius Gracchus, a rich but reform-minded politician. Gracchus, among others, was worried that the free, farm-owning common Roman would go extinct if the current trend of rich landowners seizing farms and replacing farmers with slaves continued. Without those commoners, Rome’s armies would be drastically weakened. Thus, he managed to pass a bill through the Centuriate Assembly that would limit the amount of land a single man could own, distributing the excess to the poor. The Senate was horrified and fought bitterly to reverse the bill. Tiberius ran for a second term as tribune, something no one had ever done up to that point, and a group of senators clubbed him to death in 133 BCE.

Tiberius’s brother Gaius Gracchus took up the cause, also becoming tribune. He attacked corruption in the provinces, allying himself with the equestrian class and allowing equestrians to serve on juries that tried corruption cases. He also tried to speed up land redistribution. His most radical move was to try to extend full citizenship to all of Rome’s Italian subjects, which would have effectively transformed the Roman Republic into the Italian Republic. Here, he lost even the support of his former allies in Rome, and he killed himself in 121 BCE rather than be murdered by another gang of killers sent by senators.

The reforms of the Gracchi were temporarily successful: even though they were both killed, the Gracchi’s central effort to redistribute land accomplished its goal. A land commission created by Tiberius remained intact until 118 BCE, by which time it had redistributed huge tracts of land held illegally by the rich. Despite their vociferous opposition, the rich did not suffer much, since the lands in question were “public lands” largely left in the aftermath of the Second Punic War, and normal farmers did enjoy benefits. Likewise, despite Gaius’s death, the Republic eventually granted citizenship to all Italians in 84 BCE, after being forced to put down a revolt in Italy. In hindsight, the historical importance of the Gracchi was less in their reforms and more in the manner of their deaths – for the first time, major Roman politicians had simply been murdered (or killed themselves rather than be murdered) for their politics. It became increasingly obvious that true power was shifting away from rhetoric and toward military might.

A contemporary of the Gracchi, a general named Gaius Marius, took further steps that eroded the traditional Republican system. Marius combined political savvy with effective military leadership. Marius was both a consul (elected an unprecedented seven times) and a general, and he used his power to eliminate the property requirement for membership in the army. This allowed the poor to join the army in return for nothing more than an oath of loyalty, one they swore to their general rather than to the Republic. Marius was popular with Roman commoners because he won consistent victories against enemies in both Africa and Germany, and because he distributed land and farms to his poor soldiers. This made him a people’s hero, and it terrified the nobility in Rome because he was able to bypass the usual Roman political machine and simply pay for his wars himself. His decision to eliminate the property requirement meant that his troops were totally dependent on him for loot and land distribution after campaigns, undermining their allegiance to the Republic.

A general named Sulla followed in Marius’s footsteps by recruiting soldiers directly and using his military power to bypass the government. In the aftermath of the Italian revolt of 88 – 84 BCE, the Assembly took Sulla’s command of Roman legions fighting the Parthians away and gave it to Marius in return for Marius’s support in enfranchising the people of the Italian cities. Sulla promptly marched on Rome with his army, forcing Marius to flee. Soon, however, Sulla left Rome to command legions against the army of the anti-Roman king Mithridates in the east. Marius promptly attacked with an army of his own, seizing Rome and murdering various supporters of Sulla. Marius himself soon died (of old age), but his followers remained united in an anti-Sulla coalition under a friend of Marius, Cinna.

After defeating Mithridates, Sulla returned and a full-scale civil war shook Rome in 83 – 82 BCE. It was horrendously bloody, with some 300,000 men joining the fighting and many thousands killed. After Sulla’s ultimate victory he had thousands of Marius’s supporters executed. In 81 BCE, Sulla was named dictator; he greatly strengthened the power of the Senate at the expense of the Plebeian Assembly, had his enemies in Rome murdered and their property seized, then retired to a life of debauchery in his private estate (and soon died from a disease he contracted). The problem for the Republic was that, even though Sulla ultimately proved that he was loyal to republican institutions, other generals might not be in the future. Sulla could have simply held onto power indefinitely thanks to the personal loyalty of his troops.

Julius Caesar

Thus, there is an unresolved question about the end of the Roman Republic: when a new politician and general named Julius Caesar became increasingly powerful and ultimately began to replace the Republic with an empire, was he merely making good on the threat posed by Marius and Sulla, or was there truly something unprecedented about his actions? Julius Caesar’s rise to power is a complex story that reveals just how murky Roman politics were by the time he became an important political player in about 70 BCE. Caesar himself was both a brilliant general and a shrewd politician; he was skilled at keeping up the appearance of loyalty to Rome’s ancient institutions while exploiting opportunities to advance and enrich himself and his family. He was loyal, in fact, to almost no one, even old friends who had supported him, and he also cynically used the support of the poor for his own gain.

Two powerful politicians, Pompey and Crassus (both of whom had risen to prominence as supporters of Sulla), joined together to crush the slave revolt of Spartacus in 70 BCE and were elected consuls because of their success. Pompey was one of the greatest Roman generals, and he soon left to eliminate piracy from the Mediterranean, to conquer the Jewish kingdom of Judea, and to crush an ongoing revolt in Anatolia. He returned in 67 BCE and asked the Senate to approve land grants to his loyal soldiers for their service, a request that the Senate refused because it feared his power and influence with so many soldiers who were loyal to him instead of the Republic. Pompey reacted by forming an alliance with Crassus and with Julius Caesar, who was a member of an ancient patrician family. This group of three is known in history as the First Triumvirate.

Busts of the members of the First Triumvirate: Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey.

Each member of the Triumvirate wanted something specific: Caesar hungered for glory and wealth and hoped to be appointed to lead Roman armies against the Celts in Western Europe, Crassus wanted to lead armies against Parthia (i.e. the “new” Persian Empire that had long since overthrown Seleucid rule in Persia itself), and Pompey wanted the Senate to authorize land and wealth for his troops. The three of them had so many clients and wielded so much political power that they were able to ratify all of Pompey’s demands, and both Caesar and Crassus received the military commissions they hoped for. Caesar was appointed general of the territory of Gaul (present-day France and Belgium) and he set off to fight an infamous Celtic king named Vercingetorix.

From 58 to 50 BCE, Caesar waged a brutal war against the Celts of Gaul. He was both a merciless combatant, who slaughtered whole villages and enslaved hundreds of thousands of Celts (killing or enslaving over a million people in the end), and a gifted writer who wrote his own accounts of his wars in excellent Latin prose. His forces even invaded England, establishing a Roman territory there that lasted centuries. All of the lands he invaded were so thoroughly conquered that the descendants of the Celts ended up speaking languages based on Latin, like French, rather than their native Celtic dialects.

Caesar’s victories made him famous and immensely powerful, and they ensured the loyalty of his battle-hardened troops. In Rome, senators feared his power and called on Caesar’s former ally Pompey to bring him to heel (Crassus had already died in his ill-considered campaign against the Parthians; his head was used as a prop in a Greek play staged by the Parthian king). Pompey, fearing his former ally’s power, agreed and brought his armies to Rome. The Senate then recalled Caesar after refusing to renew his governorship of Gaul and his military command, or allowing him to run for consul in absentia.

The Senate hoped to use the fact that Caesar had violated the letter of republican law while on campaign to strip him of his authority. Caesar had committed illegal acts, including waging war without authorization from the Senate, but he was protected from prosecution so long as he held an authorized military command. By refusing to renew his command or allow him to run for office as consul, he would be open to charges. His enemies in the Senate feared his tremendous influence with the people of Rome, so the conflict was as much about factional infighting among the senators as fear of Caesar imposing some kind of tyranny.

Caesar knew what awaited him in Rome – charges of sedition against the Republic – so he simply took his army with him and marched off to Rome. In 49 BCE, he dared to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy, the legal boundary over which no Roman general was allowed to bring his troops; he reputedly announced that “the die is cast” and that he and his men were now committed to either seizing power or facing total defeat. The brilliance of Caesar’s move was that he could pose as the champion of his loyal troops as well as that of the common people of Rome, whom he promised to aid against the corrupt and arrogant senators; he never claimed to be acting for himself, but instead to protect his and his men’s legal rights and to resist the corruption of the Senate.

Pompey had been the most powerful man in Rome, both a brilliant general and a gifted politician, but he did not anticipate Caesar’s boldness. Caesar surprised him by marching straight for Rome. Pompey only had two legions, both of whom had served under Caesar in the past and, and he was thus forced to recruit new troops. As Caesar approached, Pompey fled to Greece, but Caesar followed him and defeated his forces in battle in 48 BCE. Pompey himself escaped to Egypt, where he was promptly murdered by agents of the Ptolemaic court who had read the proverbial writing on the wall and knew that Caesar was the new power to contend with in Rome. Subsequently, Caesar came to Egypt and stayed long enough to forge a political alliance, and carry on an affair, with the queen of Egypt: Cleopatra VII, last of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Caesar helped Cleopatra defeat her brother (to whom she was married, in the Egyptian tradition) in a civil war and to seize complete control over the Egyptian state. She also bore him his only son, Caesarion.

Caesar returned to Rome two years later after hunting down Pompey’s remaining loyalists. There, he had himself declared dictator for life and set about creating a new version of the Roman government that answered directly to him. He filled the Senate with his supporters and established military colonies in the lands he had conquered as rewards for his loyal troops (which doubled as guarantors of Roman power in those lands, since veterans and their families would now live there permanently). He established a new calendar, which included the month of “July” named after him, and he regularized Roman currency. Then he promptly set about making plans to launch a massive invasion of Persia.

Instead of leading another glorious military campaign, however, in March of 44 BCE Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators who resented his power and genuinely desired to save the Republic. The result was not the restoration of the Republic, however, just a new chapter in the Caesarian dictatorship. Its architect was Caesar’s heir, his grand-nephew Octavian, to whom Caesar left (much to almost everyone’s shock) almost all of his vast wealth.

Mark Antony and Octavian

Following his death, Caesar’s right-hand man, a skilled general named Mark Antony, joined with Octavian and another general named Lepidus to form the “Second Triumvirate.” In 43 BCE they seized control in Rome and then launched a successful campaign against the old republican loyalists, killing off the men who had killed Caesar and murdering the strongest senators and equestrians who had tried to restore the old institutions. Mark Antony and Octavian soon pushed Lepidus to the side and divided up control of Roman territory – Octavian taking Europe and Mark Antony taking the eastern territories and Egypt. This was an arrangement that was not destined to last; the two men had only been allies for the sake of convenience, and both began scheming as to how they could seize total control of Rome’s vast empire.

Mark Antony moved to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where he set up his court. He followed in Caesar’s footsteps by forging both a political alliance and a romantic relationship with Cleopatra, and the two of them were able to rule the eastern provinces of the Republic in defiance of Octavian. In 34 BCE, Mark Antony and Cleopatra declared that Cleopatra’s son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, was the heir to Caesar (not Octavian), and that their own twins were to be rulers of Roman provinces. Rumors in the west claimed that Antony was under Cleopatra’s thumb (which is unlikely: the two of them were both savvy politicians and seem to have shared a genuine affection for one another) and was breaking with traditional Roman values, and Octavian seized on this behavior to claim that he was the true protector of Roman morality. Soon, Octavian produced a will that Mark Antony had supposedly written ceding control of Rome to Cleopatra and their children on his death; whether or not the will was authentic, it fit in perfectly with the publicity campaign on Octavian’s part to build support against his former ally in Rome.

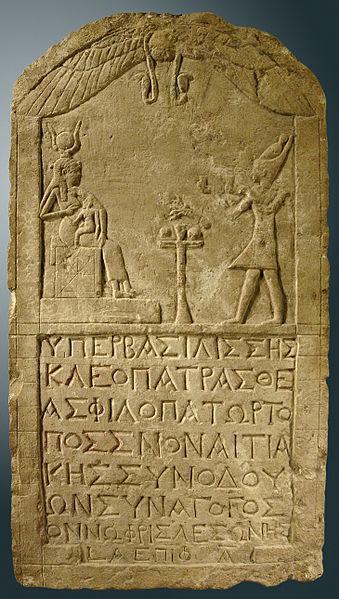

A dedication featuring Cleopatra VII making an offering to the Egyptian goddess Isis. Note the remarkable mix of Egyptian and Greek styles: the image is in keeping with traditional Egyptian carvings, and Isis is an ancient Egyptian goddess, but the dedication itself is written in Greek.

When he finally declared war in 32 BCE, Octavian claimed he was only interested in defeating Cleopatra, which led to broader Roman support because it was not immediately stated that it was yet another Roman civil war. Antony and Cleopatra’s forces were already fairly scattered and weak due to a disastrous campaign against the Persians a few years earlier. In 31 BCE, Octavian defeated Mark Antony’s forces, which were poorly equipped, sick, and hungry. Antony and Cleopatra’s soldiers were starved out by a successful blockade engineered by Octavian and his friend and chief commander Agrippa, and the unhappy couple killed themselves the next year in exile. Octavian was 33. As his grand-uncle had before him, Octavian began the process of manipulating the institutions of the Republic to transform it into something else entirely: an empire.

When Octavian succeeded in defeating Marc Antony, he removed the last obstacle to his own control of Rome’s vast territories. While paying lip service to the idea that the Republic still survived, he in fact replaced the republican system with one in which a single sovereign ruled over the Roman state. In doing so he founded the Roman Empire, a political entity that would survive for almost five centuries in the west and over a thousand years in the east.

This system was called the Principate, rule by the “First.” Likewise, although “Caesar” had originally simply been the family name of Julius Caesar’s line, “Caesar” came to be synonymous with the emperor himself by the end of the first century CE. The Roman terms for rule would last into the twentieth century CE: the imperial titles of the rulers of both Russia and Germany – “Tsar” and “Kaiser” – meant “Caesar.” In turn, the English word “emperor” derives from imperator, the title of a victorious Roman general in the field, which was adopted as yet another honorific by the Roman emperors. The English word “prince” is another Romanism, from Princeps Civitatis, “First Citizen,” the term that Augustus invented for himself. For the sake of clarity, this chapter will use the anglicized term “emperor” to refer to all of the leaders of the Roman imperial system.

Augustus

The height of Roman power coincided with the first two hundred years of the Roman Empire, a period that was remembered as the Pax Romana: the Roman Peace. It was possible during the period of the Roman Empire’s height, from about 1 CE to 200 CE, to travel from the Atlantic coast of Spain or Morocco all the way to Mesopotamia using good roads, speaking a common language, and enjoying official protection from banditry. The Roman Empire was as rich, powerful, and glorious as any in history up to that point, but it also represented oppression and imperialism to slaves, poor commoners, and conquered peoples.

Octavian was unquestionably the architect of the Roman Empire. Unlike his great-uncle, Julius Caesar, Octavian eliminated all political rivals and set up a permanent hereditary emperorship. All the while, he claimed to be restoring not just peace and prosperity, but the Republic itself. Since the term Rex (king) would have been odious to his fellow Romans, Augustus instead referred to himself as Princeps Civitatus, meaning “first citizen.” He used the Senate to maintain a facade of republican rule, instructing senators on the actions they were to take; a good example is that the Senate “asked” him to remain consul for life, which he graciously accepted. By 23 BCE, he assumed the position of tribune for life, the position that allowed unlimited power in making or vetoing legislation. All soldiers swore personal oaths of loyalty to him, and having conquered Egypt from his former ally Mark Antony, Augustus was worshiped there as the latest pharaoh. The Senate awarded Octavian the honorific Augustus: “illustrious” or “semi-divine.” It is by that name, Augustus Caesar, that he is best remembered.

Despite his obvious personal power, Augustus found it useful to maintain the facade of the Republic, along with republican values like thrift, honesty, bravery, and honor. He instituted strong moralistic laws that penalized (elite) young men who tried to avoid marriage and he celebrated the piety and loyalty of conservative married women. Even as he converted the government from a republic to a bureaucratic tool of his own will, he insisted on traditional republican beliefs and republican culture. This no doubt reflected his own conservative tastes, but it also eased the transition from republic to autocracy for the traditional Roman elites.

As Augustus’s powers grew, he received an altogether novel legal status, imperium majus, that was something like access to the extraordinary powers of a dictator under the Republic. Combined with his ongoing tribuneship and direct rule over the provinces in which most of the Roman army was garrisoned at the time, Augustus’s practical control of the Roman state was unchecked. As a whole, the legal categories used to explain and excuse the reality of Augustus’s vast powers worked well during his administration, but sometimes proved a major problem with later emperors because few were as competent as he had been. Subsequent emperors sometimes behaved as if the laws were truly irrelevant to their own conduct, and the formal relationship between emperor and law was never explicitly defined. Emperors who respected Roman laws and traditions won prestige and veneration for having done so, but there was never a formal legal challenge to imperial authority. Likewise, as the centuries went on and many emperors came to seize power through force, it was painfully apparent that the letter of the law was less important than the personal power of a given emperor in all too many cases.

One of the more spectacular surviving statues of Augustus. Augustus was, among other things, a master of propaganda, commissioning numerous statues and busts of himself to be installed across the empire.

This extraordinary power did not prompt resistance in large part because the practical reforms Augustus introduced were effective. He transformed the Senate and equestrian class into a real civil service to manage the enormous empire. He eliminated tax farming and replaced it with taxation through salaried officials. He instituted a regular messenger service. His forces even attacked Ethiopia in retaliation for attacks on Egypt and he received ambassadors from India and Scythia (present-day Ukraine). In short, he supervised the consolidation of Roman power after the decades of civil war and struggle that preceded his takeover, and the large majority of Romans and Roman subjects alike were content with the demise of the Republic because of the improved stability Augustus’s reign represented. Only one major failure marred his rule: three legions (perhaps as many as 20,000 soldiers) were destroyed in a gigantic ambush in the forests of Germany in 9 CE, halting any attempt to expand Roman power past the Rhine and Danube rivers. Despite that disaster, after Augustus’s death the senate voted to deify him: like his great-uncle Julius, he was now to be worshipped as a god.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

First Triumvirate – Andreas Wahra

Cleopatra VII – Jastrow

Augustus Caesar – Till Niermann

This chapter has been derived with minor modifications from Chapter 8: The Roman Republic and Chapter 9: The Roman Empire in Western Civilization: A Concise History.