2 Stepping Stones to The New World

- Next Topic- Pirates and Protestants

- Week 4: Paper #1 Due

As we saw last chapter there were still the islands of the Atlantic to visit and therefore complete the puzzle that would be the New World to ‘Old World’ Europeans. In that effort, we can not take Columbus’s stop in La Gomera, in 1492 as he set sail for his first voyage, as a mistake or accident.

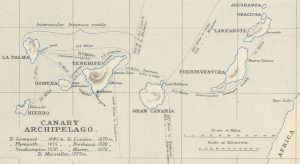

The Canary Island, off the coast of North Africa was a well known colony of Castile in the 1300s. The popular island, however, had faded into obscurity as the boom of exploratory activity by Genoese, Castilians, and Portuguese alike slowed. This fact, however, did not deter 2 Normans, Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de la Salle, as they set sail for the Canary Islands in 1402. Going in search of gold and wealth or perhaps a new people to enslave or even trees to cut down.

Bound for The Canaries

Salle was a knight taking part in the expedition to find his fortune and after Béthencourt expressed his “wish” to spread Christianity to the ‘heathens’ the pair were able to set sail, along with a crew, on May 1st, 1402. However, as was the norm, the voyage was impeded by heavy winds and forcibly found themselves docking in Galicia for several days. Once able they set off only to make a stop in the Andalus port of Cádiz, where Béthencourt found himself in trouble.

Being an unknown in the port city, Béthencourt found himself and the ship’s crew accused of theft. Then rumors began to spread of the ships not being properly provisioned and 27 of the crew left his employ. It would take 8 days for all this to be cleared and for Béthencourt, along with what remained of the crew, to arrive on the small island of Graciosa; which was near the larger island of Lanzarote.

Life in The Canaries

After the men arrived in Graciosa they crossed over on to Lanzarote. They, however, were met with issues in trying to communicate with the natives. Eventually some of the Guanche people came down from their mountain homes to establish an uneasy yet friendly relationship. Béthencourt, with permission from the leader, gave orders for a fort to be built and left Bertin de Berneval in charge as he and Salle ventured forth to the next island.

Using similar tactics, Béthencourt and Salle attempted to capture natives on Fuerteventura in efforts to establish themselves. After frustratingly fruitless 8 days of attempting to establish relations with the natives, Béthencourt returned to Lanzarote and then went on to Spain. Yet, during this time away in search of supplies and a meeting with the King, Berneval would capture the Lanzarote ruler and leave Salle without recourse on the island of Los Lobos. Berneval later went on to take over a ship to bring him back to Spain.

Upon his return, Béthencourt and Salle began a hostile takeover in efforts to firmly colonize and claim the islands for Castile. Béthencourt having been named lord of islands by King Henry III as well as given permission to collect ⅕ th of all profits made. Things would move swiftly once the escape artist of the Lanzarote ruler finally aquized to be baptized into Christianity and took the name of Louis.

The Struggle for Control

With Lanzarote settled the Normas turned their focus to the remaining islands which did not prove so easy to call to heel. Their continued effort were, however, hindered as the funds and supplies Béthencourt had brought back from Spain began to dwindle. Salle left for Seville and never returned while Béthencourt went and returned with a fresh batch of settlers. Soon frustrated with his lack of progress on Gran Canaria, Béthencourt, left Lanzarote and Fuerteventura in the hands of his nephew Maciot de Béthencourt. Béthencourt would travel to Spain, Rome, and France sending settlers back to the islands but never returning himself. He died in Normandy, France in 1425.

Yet, a year prior to his death Béthencourt received assistance from The Navigator in the form of a 2,500 man strong expedition sent to capture Gran Canaria. Despite the islands being under Castilian control The Navigator kept up intermittent attacks of the island and failed each time as he did the first. By 1455, settlers and Christians lived on all of the islands except for Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma. Castile would not be able to wrestle control of the islands until the late 15th century. As with what would happen with those of the New World, Europeans would a century later question the existence of these natives given their precepts of Christianity.

Power to The People

As with all Eurocentric history left of extinct peoples, the true history of the Guanches people remains heavily clouded. This name for example was a catch all term for all of the native populations of the various islands. The Guanches are, however, believed to be connected to the North African Berber tribes. Yet, again this is not known for certain as none survived into the 17th century. Credit must be given where credit is due and, while their true history has been lost to time, we must remember that these “pagan” people withstood years of European invasions and even after Béthencourt’s arrival not all of the islands fell.

The resistance came to an end in time and all islands where put under Spanish control with waves of settlers coming and displacing the natives. The Guanches were soon erased by Portuguese, Genoese, Catalans, Jews, Moors, and moriscos. By the 1550s the island saw English settlers arrive with trading of cloth for sugar and dyes, found in wood, birthing a bustling coastline. We must, however, note that the infamous veins of gold were never found despite being so close to North Africa. It soon became known that the islands were better suited to something even better than gold… Sugar! What natives remained were enslaved alongside imported Africans from Portuguese Guinea for its cultivation and refinement.

Portugal and The Atlantic

While Prince Henry failed in the Canary Islands, Portugal managed to acquire several Atlantic islands of its own without experience resistance whatsoever.

In 1420, sailors João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira were caught in a storm at sea and sought safety from the elements on the island of Porto Santo. There were no signs of life other than that of the volcano on the island next door; Madeira. The sailors quickly understood, after a brief exploration of Madeira, that they had struck proverbial gold. The island had fertile soil thanks to its resident volcano. Then there was also the added fact, that they had not been sent off course to a point from which they could not find their way back home.

Madeira in particular was quite close to both the Canary islands and Lisbon. This, however, begs the question why had the island not been “discovered” before? The answer would be that while it had been noticed, Portugal could not be bothered until reports, in 1417, of Castilian ships as well as Gonçalves and Vaz’s voyage were put forth. Portugal’s John I soon decided to send in settlers to prevent Castilian takeover as well as that of any other European countries. Gonçalves and Vaz were sent back with the settlers and accompanied by Italian Bartolomeo Perestrello who had been given command of Porto Santo.

Porto Santo and Madeira

By 1425, waves of settlers were arriving in the highly prosperous islands. Not to be left out, Columbus would venture to the island as well and marries Perestrello’s daughter cementing ties to a known Portuguese family; although they too had Italian roots. While the world as had been known continued to expand that of the mariners remained quite small which made such a marriage quite advantageous.

Madeira soon had swaths of land cleared for the planting of wheat and production of sugar. The sugar being a prime crop given the sufficient amounts of rain that fell to sustain the crop. As with all other European colonies, Genoa became the financier behind the rapid rise of sugar mills while Portugal was the importer of laborers; laborers that were used in conjunction with those of Guinea and surviving Guanches. The profits made, however, went nearly entirely to the financiers.

Also grown on the island were grains and grapes. The grapes being turned into the wine which bears its name till this day. By 1455, Madeira, was a wealthy sugar producer which would change with the emergence of sugar production in the New World in the 1500s. Never would the island reach its previous wealth status again. With Madeira and Porto Santo well established it was on to the Azores for Portugal.

Portugal, The Azores, and Africa

With the “discovery” of the Azores group of islands Portugal once again began shipping settlers out in 1439. Although useless for the production

of sugar these islands became producers of wine and grain.

Mina was the name of the first Portuguese settlement in Ghana; known today as Elmina. With contact made between them and the natives, traders quickly set up shop in the form of feitorias around the 1440s. This “factory” was the first trading posts in a coastline soon filled with other such “factories”. Ships docked loaded with cloth, beads, horses, brass goods, and guns as well as other weapons. This would all be unloaded and then replaced

with gold, spices, ivory and slaves for the return trip home. From mid-1400s to about 1530, there were nearly 156,000 enslaved Africans. To further facilitate things Portugal added the Cape Verde Islands to their sphere of control. A particular astute addition given its, 400 miles off the West African coast, location. The name being an ironic reference to the lush greenery of the African coast itself as opposed to the opposite conditions of the islands themselves.

In their attempt to perfect the volta da mina, sailors began using these islands, much like the Canaries, as stopping points for resupply and repair on their journeys. Soon the largest of the Cape Verde Islands, Santiago, had its own settlements well established by the 1460s. Similarly to the Madeira, there were no natives from which to “discover” the land. Santiago, along with the other islands, a stepping stone for sailors and merchants alike as well as major player in the slave trade.

The Pope and Slavery

The papacy was very interested in the slave trade and also gave its input on the matter. On January 8th , 1455, for example, Pope Nicholas V praised Afonso V for his participation in colonizing Madeira and the Azores as well as the royals endeavors in Africa and the push for conversion. The Pope even gave permission for the enslavement of “non-believers”, to continue. His input was of great value! Not just because it gave credence to religion as a justification for slavery but also because of the enormous power held by the church in Europe at the time. The Pope’s blessing was giving slavers carte blanche. Their power so great that colonization of the Atlantic and Caribbean had to be backed monetarily by the Genoese as well as the church. As with the infamous sanctioning of hits by the “godfather” in mob films, the colonization of any land had to be sanctioned by: Portugal, Castile, Aragon, and the Vatican.

Europeans in these times were struggling with the reality that the world as they had known it was actually larger than previously perceived. In seeking an answer to this issue they turned to what had held true… the church, the hatred for ‘Infidels’, and the driving need left from the Crusades to save others from hell by bringing them into the fold of Christendom. A belief cemented and provided for by the Catholic Church.

Diplomatic Relations

The high octane race of conquest and colonization proved too much for the strenuous relationship of Portugal and Castile. The constant battle of “its mine” and “no, its mine” was finally put to rest by the Vatican in a series of treaties:

- Treaty of Alcáçovas, 1479

- Papal Bull: Inter Caetera, 1493

- Treaty of Tordesillas, 1494

All of which help to quash the constant feud between the two crowns but the last of which had a ripple effects well beyond those initially imagined. The demarcation line established by it would lead to a massive blood letting and execution of all non-Catholics unwilling to convert.

During all this Columbus was not quietly wasting away with his wife in Porto Santo. To the contrary, Columbus was an active participant in the race for Atlantic colonization and conversion. It was this experience with which the Admiral would sail into the West Indies on his first voyage with. The West Indies were a ripe field for conversion and with a large people for enslavement; although he did not find the environment to be as grandiose as once hoped for.

The Admiral

The Admirals arrival in the Caribbean proved to be the beginning of many things one of which was a change in European vernacular. The doctor aboard Columbus ship, for the second voyage 1493-1496, Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca was the first to have written descriptive names for the natives as ‘Taino’ and ‘Caribs’ as well as ‘Arawak’. These tribal distinctions being given not by the natives themselves but by the Europeans based on their relationship to one another. The Tainos, for example, being peaceable people more than willing to cooperate with the Spanish while the Caribs were warriors and cannibals who killed and ate Tainos while fighting off the Europeans. While Chanca is the first to put the terms to paper, Columbus is said to have used them which caused Chanca to, perhaps, rewrite another people’s history. Those of the Greater Antilles were Tainos and those of the smaller islands were Carib ‘cannibals’.

These divergent personalities, however, are questioned by scholars who doubt such could have existed. Other argue that these natives have not gone extinct as we’ve been led to believe. What can not be argued is that, either Taino, Carib or Arawak, life as had been known was forever changed. Between the violence and European introduced illnesses and diseases nothing would ever be the same.

The Natives: Tainos & Caribs

Prior to European arrival wars happened and ended with hostility aplenty, normal amongst any people; take England and France for example. It was, however, to be religion the dividing factor used to categorize the people. Yet, Columbu’s terms carried sway and were later used by Kalinago to describe the people of Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia and St. Vincent as “black Caribs”; for example.

With Arawak becoming the catch all term for those in the smaller islands since its people all spoke variations of Arawak. By the time Robinson Crusoe was published in 1719, the majority of the Atlantic and Caribbean natives were long gone, yet, their European given characteristics and history were clearly depicted in the novel.

Other writers continued the misinformation of Carib “cannibals” although some went to great lengths to make the cannibalism a thing of vengeance rather than the nature of or natural to the people.

Columbus & Hispaniola

When the Admiral arrived, he would have encountered a people far from barbaric and paganly uncivilized. The ‘Tainos’ lived in organized settlements with populations of 5,000 in the larger ones. Here the men hunted and fished while women worked the land, birthed and raised children, as well as performed other duties. There was even a hierarchy system in place. While exact number of pre-Columbian population varies, there is no doubt that the majority died from the European brought illnesses and diseases. The majority of those who survived dying due to overwork and harsh labor or murder. Columbus and his crew had advanced weaponry and diseases to help with the subjugation and colonization of the island. These same weapons not only provided tactical advantages but they also served as something tradable for slaves.

This is not to say that the people were overtaken easily or without resistance. Not on Hispaniola or farther south in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. The Caribs, later known as black Caribs, but up a fight measure for measure until 1796. European incursions into Nicaragua and Honduras saw the Miskito people cause “intolerable” chaos for them as well. The Amazonians remained largely undisturbed due to their protective jungle . A jungle that would prove a safe haven for runaway Africans and home to their resistance efforts.

The Resistance

While there were those resistance movements within the jungles there was quiet forms of resistance amongst those enslaved as well. As historian Matthew Restall demonstrates, the “accidental” breaking of tools, slow work and even leaving for areas uncrossable by Europeans. Those revolts that did take place where often swiftly put down. Although, the Spanish control of the island was facilitated by those natives who peaceably collaborate with the invaders. Take Juan Garrido, for example, a West African slave brought to Hispaniola in 1502/1503 and later freed. He would go on to visit Lisbon and aid in the exploration of Puerto Rico and Cuba as well as that of Mexico in 1519.

Then there was the control achieved through alliances and sex. Alliances brokered for strategic political or personal reasons. The there was the sex. Spanish men travelling to parts unknown without women found some more than willing to be mistresses. Then there were the unwilling women; raped or trade for by their fathers. This causing the mestizaje effect and establishing a non-rigid class system.

Columbus & La Navidad

In 1493, Columbus was anxious to reach Hispaniola and see how La Navidad was doing. And so taking a different route, the Admiral sailed to what is now Guadeloupe, Montserrat, Antigua, St. Kitts, St. Croix, and Puerto Rico. Finally docking in Hispaniola that November, Columbus was in for a big shock. There was nothing left of La Navidad but burnt rubble and European clothing strewn about.

He was, however, undeterred and set his men to quickly find another location. Once done, construction of La Isabella began and this was the beginning of colonialism in the Americas. This construction served to further enrage the natives to which Columbus responded with deadly attacks on the people in 1494 and 1495. Of those not killed 1,600 were enslaved and 550 of which were sent to Spain. He was operating under the same code of conduct as the Old World. In fact, the Spanish crown granted permission for the sale and capture of Caribbeans in 1495. Those not sold remained to pan for gold and raise cassava and other crops.

Columbus is In Trouble!

Before the start of the Admiral’s return trip to Castile in March of 1494, settlers were upset. Upset at the mere thought of having to do manual labor when the land they had been given was supposed to be their part in the repartimiento system. This was in addition to their disagreements over the feitoria’s. Leaving his brother, Bartolomé, in charge Columbus would leave the island on the brink of a powder keg explosion. While he traveled to Cuba and looked over St. Jago (today’s Jamaica), Bartolomé was found hard pressed to deal with an insurrection. At first, in August of 1494, the settlers were happy after the discovery of a gold vein. Then there was the very astute move of the capital to the strategic location of Santo Domingo with access to a good harbor. These sentiments would, however, turn negative! With a charge led by Francisco Roldán, these disgruntled settlers took to the west and forced people to work outside of the jurisdiction of the the appointed leader.

By the time Columbus made it to Castile, he found the bad news had preceded him. Yet, he had little time to care about that fact with the natives becoming increasingly enraged. The Catholic monarchs were obviously concerned, yet, they did grant the Admirals request for funding of a 3rd voyage. With the 6 ship fleet, Columbus left Spain in May 30th, 1498.

Hispaniola Damage Control

As was the norm, Columbus would see land on July 31st but not the land he had been aiming to reach. Ending up farther south, it would take Columbus a month to finally make it to Hispaniola. Upon arrival it was clear the situation was worse than he had believed and in response he began giving encomiendas to the enraged settlers. Chiefs, or caciques, would be placed in charge of the enslaved natives whom in turn had to pay tribute to the Spanish estate owners; or encomenderos. These chiefs would be compensated with some payment, conversion, and “protection” from abuse or attacks; similar to mafia protection rackets.

The give away of land grants, while appealing to the settlers, angered the Spanish royals. Having no authority to grant land, Columbus had overstepped. In response, the royals sent a new governor named Francisco de Bobadilla, began granting land themselves, and issued a cédula (decree) in 1500 which freed natives brought as slaves to Spain by Columbus. Bobadilla took over the governorship and stemmed the unrest by sending Columbus, and his brothers Diego and Bartolomé, back to Spain in chains.

Yet Another Governor!

Right after the chained Columbus brothers were loaded onto the returning ship, Spain sent a new governor in. Arriving in 1502 with 2,500 settlers was the new governor Nicholás de Ovando and Bartolomé de las Casas.

The determined new Governor, Ovando, was on a mission! His first action was to send insurector Roldán back to Spain and put more natives into mines so that the promised gold could make it to the royals. This would become the foundation of Spain’s colonial leyenda negra or black legend.

Despite receiving reports of abuse and outright murder being committed by Ovando, a royal cédula was issued on December 20th, 1503 approving the enslavement of people from other islands; who could be used for any purpose and in any Spanish territory. Ovando personally massacred many of the native chieftains in 1504!

Columbus Sails Again

Columbus set sail for one last trip on May 11th, 1502, with 4 ships and orders to stay away from Hispaniola. Sailing to Honduras, Columbus would explore the Bay Islands as well as the Central American coastline. In April 1503 he set off for Hispaniola but ended up stranded in Jamaica. Sending for help, it would take Ovando a year to finally give in and assist the stranded mariners. Finally rescued, Columbus and the crew would return to Spain in 1504. It was here that Columbus would spend his last days and died in Valladolid in 1506. Spending his last days with a religious devoutness and style thanks to his saved gold; although without any of his titles.

While credit for the “discoveries” have been historically given to Columbus, none of the worlds and islands would bear his name but rather that of Amerigo Vespucci. Perhaps this was the case given Vespucci’s more accurate depiction of the New World as simply that rather than the much searched for East. His voyage having taken place in the late 1490s.

Bartolomé de las Casas

Throughout Ovando’s governorship and the last days of Columbus seafaring ways, priest Bartolomé de las Casas was reaping the benefits of his encomienda and steadily becoming a very rich man. He spent his time in Hispaniola teaching Christianity to the natives while assisting in keeping any rebellions from fermenting. However, during his tenure he would see Ovando step down and Columbus’s son Diego assume the governorship in 1509. With the time also leading to the settling of Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, and Cuba in 1511. Las Casas would venture on to Cuba as a chaplain having recently been ordained, yet, not fully converted.

Las Casas would witness the horrors of Spanish rule in Cuba and come to the understanding that the encomienda system needed to end. He would begin his campaign for such and started by giving up his own. The Laws of Burgos of 1512 attempted to curb the abuse, yet, little is known as to whether the laws edicts were actually followed. The new territories, however, followed the same pattern as Hispaniola with the depletion of gold stores, raising of livestock, depopulation, and outright neglect. Yet, it must be noted that an estimated 60 tons of gold was mined by the natives and sent to Spain in the 1500s. With the first sugar mill in Hispaniola opening its doors in 1513 and mills cropping up in Puerto Rico next.

las Casas and Slavery

In a truly catastrophic lightbulb moment, las Casas came up with the ingenious idea of switching to African labor in 1517. By the end of the 1500s about 100,000 Africans were brought and parceled out to the Spanish colonies. Traders bringing in these slaves, however needed to hold an asiento for the privilege. The asiento being a license given by Spain and which created a monopoly on goods or trade routes; in this case slaves. Said license was usually given as part of certain peace agreements. The asiento would grant the receiver the right to sell a fixed number of enslaved Africans to Spain’s colonies for a small fee.

Las Casas would continue his work to protect natives throughout the acquired territories of Spain while working on his History of the Indies; even impeding the colonization of Nicaragua for a brief period. His book would not be published until after his death. Soon slavery would take root birthing a new system and conquistadores would gain control of Central America around 1510. 1513 would see the arrival of Vasco Núñez de Balboa and a bloody swath of bodies could be carved into the native population; with Panama being settled in 1519.

Spain: Blood and Glory

Eager English, Dutch and French sailors soon took to the high seas looking for a piece of the action. The trips from Europe to the Caribbean was now a well established “cruise” route. The Caribbean represented a place of fantasies, lawlessness and free of social norms while simultaneously being brutal, violent and deadly. Surely different from the stories read in the comfort of their European homelands the sailors soon managed to mesh together the stories and reality. The era of Exploration was in full swing.

As for the West Indies, it too would see the start of a new era. An era fraught with the arrival of western Europeans, greedy wealth seekers, and the dashed hopes of those seeking gold where there was none. Money would have to be made through different means…

After adding Mexico to their crown of colony money makers, settlers throughout the territories sent shipments of sugar, gold and pearls back to Spain. Forcing first the natives and later Africans to dive into oyster bed for the pearls. News of which, among other expeditionary gossip, was now quickly being spread thanks to the 1450s innovation of the printing press.

- Next Topic- Pirates & Protestants

- Week 4: Paper #1 is Due

© 2020. This work is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Licensed by Mahalia Méhu under a Creative Commons Attribution- Share Alike 4.0 International License.