34 Conquering Challenging Courses

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will:

- Learn to prepare for the class in advance

- Learn how to use the Syllabus to plan and set goals

- Acquire strategies for staying on track and engaged throughout the semester

- Learn how to get help

Student Spotlight

This video will offer you ways to navigate challenging courses. With this video, you will be able to practice some tips that make a challenging course easier.

Introduction

“That class is an easy A!”

“That class ruins your GPA – beware!”

“Best class I’ve ever taken – you have to work for it but I learned so much.”

Rumors tend to swirl around different college courses, and it can be tempting to go into a class with these preconceptions in mind. However, if you enter a course with the fixed mindset that it will be impossibly challenging, then you start off with a negative outcome (failing) in mind, and the goal then becomes simply to pass the class, with learning as a secondary goal.

As you plan and take courses toward your major, you will find that some classes are naturally easier for you than others. With any class you take (or are thinking about taking), start by asking: “What are my goals in taking this class?”

In this chapter, we will start by identifying your goal in taking a class and using the class syllabus as a way to gauge and pace yourself and then apply some of the techniques from other sections in helping to keep you on track.

Know what you’re getting into and plan and prepare accordingly!

Preparing for the Class in Advance

Before diving into a class, it is important to take a step back and be clear on why you are taking the class. This is especially true for a class that you know will be challenging. Is this class for your major or for a core requirement? Are you taking it out of interest? You want to start the class with clear expectations.

It is also worthwhile to ask yourself why you feel this class will be a challenge and to prepare in advance to confront potential barriers that might arise. Will the class be challenging because of the amount of reading and writing, or will it be challenging because it requires an immense amount of problem sets and math? In both of those cases, there are places on campus for help, such as the Writing Center and various tutoring centers (see a list at the end of this section).

If this challenging topic is new to you – or even if it isn’t – take the time to learn a little about it before the class begins. This can be from YouTube videos or web pages for the same course offered someplace else. One great way to get an overview is to find a website on the subject that is written for kids – it will be explained in a simple way without technical jargon. If you enter class on the first day with some understanding of the subject, this can make the material seem less overwhelming at the start.

Depending on when you register for a class, you may be able to see the syllabus in advance. The syllabus is so important that we go through it step by step in the next section.

Using the Syllabus to Plan and Set Goals

Perhaps the most important document to read in any course is the syllabus. The syllabus contains crucial information, such as the schedule of topics, major assignments and due dates, and how to get in touch with the instructor and when and where their office hours are. Before registering for a class, chances are that there is a syllabus available online for that class. You can often find the syllabus on the departmental website under course information.

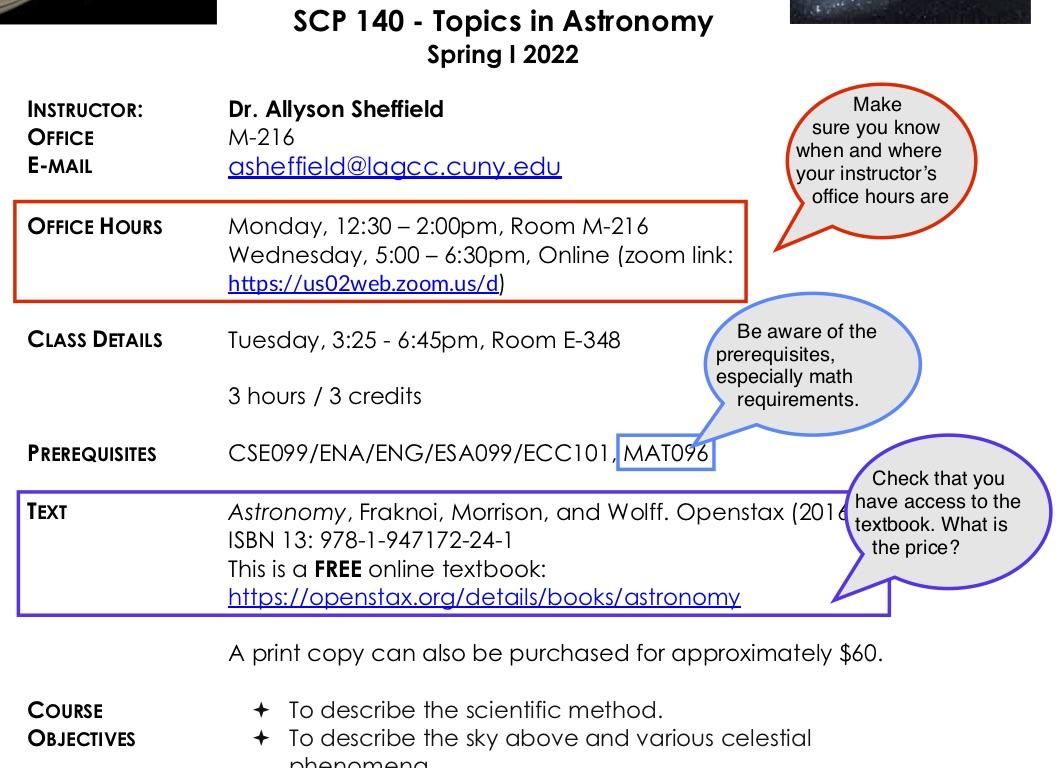

Open the syllabus for one of your classes and do an initial scan. Figure 1 shows you an example of a sample syllabus for a course, with some of the key pieces of information to immediately note.

Figure 1 shows you an example of a sample syllabus for a course, with some of the key pieces of information to immediately note.

Figure 1 – Sample syllabus with key points highlighted.

As you look at the image answer the following questions. Alternatively review an accessible version of the syllabus to answer the questions.

- When and where are my instructor’s office hours?

- How do I contact my professor?

- How is my final grade broken down?

- Does this course need any prerequisites before I register? Meaning, do I need to take any other courses before I take this one?

- Do I need to buy a textbook?

Important! Is there a Blackboard or ePortfolio page? Can you access it?

Is there anything in the syllabus that is unclear? If so, note this and plan to ask your instructor. *Before doing this, make sure the question is not answered someplace else in the syllabus!

Make a Weekly and Semester Schedule

Now that you have all of the syllabi for the semester at hand, the next step is to prioritize and put a weekly schedule for the entire semester together. You may have already started this in the Time Management activity in your Studio Hour, and this is an excellent starting point – make sure you are leaving time for adequate sleep. In the Time Management and Procrastination chapter, the section on Using the Syllabus to Prepare for the Semester goes step by step through the process of creating a schedule.

Use this calendar to decide how much time to set aside each week for study time outside of the challenging class. Remember that studying is not just reading but also creating summaries and reviewing material. For an intensive math or science class, this means working through practice problems.

Setting Goals

Time management is a crucial element of academic success. Creating a semester schedule helps you visualize what a typical week will look like and you can use this as a launch point to set goals for the class. In setting goals (for class or really anything), you want the goals to be specific and achievable.

When thinking about your goals for a class, try to be as specific as you can. For example, simply saying you will “do your best” is an admirable but vague goal; the more clear the goal is, the more likely you are to attain it (Locke & Latham 2002). How would you measure if goal of “doing your best” has been achieved? A specific goal also includes a way to assess how you are doing – say through feedback from your professor – and objectively determine if the goal has been reached.

A study which looked at how specific a goal was (for example, including the start and end date as well as a way to measure the outcome) found that students who set specific goals had a higher GPA (Acee et al. 2012). In other words, goals with measurable standards led to the greatest academic success. Interestingly, this study also found that the motivation for the goal – whether it was for personal interests or to meet the expectations of others – had an impact on the outcome of the goal. Goals that were set with others in mind, such as pleasing family members, actually led to a lower GPA.

How can you go about making the goal achievable? You want to make the goal challenging but still able to be completed. As Julian said in the video at the beginning of this section, break up your goal into small, achievable pieces. The section on Time Management discusses a framework for taking a goal and breaking it an assignment down into smaller steps. Rather than saving a research project until the end of the semester (because that’s when the due date is), instead chip away at the assignment gradually. Making a to-do list for the assignment is a great way to see the path for completing it.

Strategies for Staying On Track

Make the Most of Class Time

Some of your classes may only meet once per week – make the most of this time. If you can, get to class early and find a seat where you can see the white board and slides. Avoid distractions…by putting your phone away (even having it on your desk turned over is a distraction). There is a reason that some elementary/middle schools now require students to have their phones locked up in a box (!) during the day. Some instructors at LaGuardia may simply forbid phones in the classroom, so plan to not have it out.

Look at the syllabus before class to know what the topic for the day is. Review your notes and summaries from the previous class. If you come to class knowing the basics, you will be better suited to stay engaged. In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, or books. Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

Stay engaged during class. Just showing up and physically being there is not enough… listen with intent and ask questions if you can. Listening with intent means you know what the learning goals are and you have these in mind during the lesson. If you don’t understand the material or don’t see how it applies to the learning goal, ask. In STEM classes where equations are presented, ask to see some real world examples of problems worked out, or ask why it is important to know. If an equation seems meaningless to you, take the time to learn how, when, and why it is used in this subject.

Summarize Material

In thinking about and processing the material covered in a class or a reading, the sooner you can do this the better. As discussed in the Metacognition section, the process of active recall – accessing knowledge from your memory, rather than looking things up – helps to strengthen your understanding by creating new connections in your brain related to the topic.

At the end of class, instead of putting away everything and zipping up your backpack the second your instructor seems to be winding down (which can be a huge distraction for everyone, including your instructor), take a moment to look back at the learning goals for that class and assess if those have been met. If the main topic for that week in your Organic Chemistry class was “Free Radicals,” can you explain what this means and give some examples? It may take some time to do this without looking it up, but the more you work at it the easier it will get. Try scheduling a small block of dedicated time the same day as the class or as soon as possible after the class to review and summarize.

One way to make sure that you really understand a topic is to explain or teach it to someone else. When explaining a topic to another person, particularly someone who is new to the subject, you need to break it down into the most basic components, using little or no jargon. Does every word that you are using make sense to you? If not, take a step back and revisit that concept.

Another way that explaining to others can help your own understanding is through questions that come up. You can do this in a study group or try it on someone who has a lower (or higher) level of knowledge on the topic. Think about great tutorials you have seen on a subject and identify what made them so memorable. While memorizing definitions may seem like a good strategy right before an exam, it is a quick fix and the information will leave your short term memory once the exam is past and not make it into your long term memory.

One final method to consider when summarizing material is to create a concept map. As discussed in the Note Taking section, creating concept maps is a good way to see connections between different sub-topics within a broader subject. In understanding Climate Change, for example, you must also understand the basics of the Greenhouse Effect and how these two topics are connected. This is an especially effective method of summary for visual learners.

Read Meaningfully

Have you ever read the same paragraphs of a chapter over and over again, only to realize that you did not retain any information (you have no idea what you read)? This can be a frustrating experience, especially when the reading itself has used up precious time. Simply reading and re-reading material, which can be a natural tendency, will not necessarily lead to knowledge retention

When approaching a reading assignment, particularly one that seems daunting for some reason, how you read the material makes a difference. The same strategies for summarizing material from class discussed above apply to reading. Before you begin reading, do a general skim of the material and have some idea of what the reading covers. Identify why this reading was assigned and how it relates to your broader learning goals in the class.

As you read, take notes and write down questions you have. The act of writing something down gets the information into your memory. Read the notes that you took and think of any connections to material you have already seen. Making these links will further strengthen the neural pathways to this subject in your brain and create new connections. For more information on reading with intent, see the chapter on Reading Skills.

Practice, Practice, Practice

With any class, especially STEM courses requiring math skills, one of the proven keys to success is to practice as much as you can. Your textbook likely has many practice problems at the end of the chapter. Look at some similar problems before doing this so you have a solving strategy in mind. You do not want to fall into a pattern of memorizing how to solve a problem (or relying on a note card or “cheat sheet” that your professor may allow you to bring into exams); instead, understand the fundamentals and then work through a variety of problems related to a concept.

Sometimes you can find different textbooks than what your professor assigned for the class (check the Library — ask a Librarian to help you find one). This is another great way to see more examples and get some additional practice. Try to schedule dedicated time each week for working on practice problems. There really is no shortcut to practicing – it will take work but it is worth it in the end.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

As detailed in Metacognition – The neuroscience of learning, tapping into prior knowledge is an excellent evidence based learning strategy. When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Some questions that you may ask yourself to access this prior knowledge in order to help you make sense of your reading include:

- Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic?

- Did you study some aspect of it in another class?

- Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material?

APPLICATION

Imagining that you were given a chapter to read in your Astronomy class about the reclassification of Pluto as a “dwarf planet,” write down what you already know about Pluto. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text? This is an excellent example of practicing retrieval learning or active recall ( Metacognition – The neuroscience of learning).

Find a Quiet Place to Study

Just as avoiding distractions during class is critical, the same goes for studying. We have found that students have embraced the Library as a quiet refuge. In addition, the library can offer space for students to be engaged in online classes and participate, with microphones on, in online class discussions.

Getting Help

Studying alone at times can be beneficial, particularly when you need to focus on a reading assignment. However, it is great to take advantage of some ways to study with others.

- Try to form a study group with other students in your class

- Visit your professors office hours. Come prepared with some specific questions and/or some problems to work on.

Here is a list of on-campus resources to keep you on track:

- The Writing Center

- Tutoring: Science Study Center, SGA

References, Licenses, and Attributions

Acee, T. W., Cho, Y., Kim, J. I., & Weinstein, C. E. (2012). Relationships among properties of college students’ self-set academic goals and academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 32(6), 681-698. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2012.712795

Baldwin, A. (2020). 5.2 Effective Reading Strategies. In College success. https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/2-3-its-all-in-the-mindset. This book, attributed to OpenStax, uses the CC BY 4.0 license. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

Kaplan, J. (2021, July 1). How to read a college syllabus – And strategize for how to best approach the course [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/mQ_Xmc_Urxw

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705