8 Strategies for Critically Engaging Secondary Sources

The following strategies are adapted, and the figures reproduced, from Mark Gaipa’s “Breaking into the Conversation: How Students Can Acquire Authority in Their Writing,” Pedagogy 4.3 (2004): 419-37. Note that these strategies may be used globally, as a way of framing an argument, or locally, as a way of engaging sources at a particular stage in an argument.

|

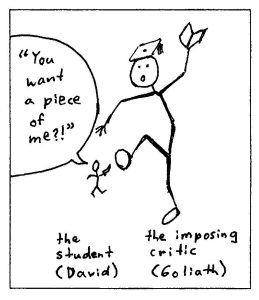

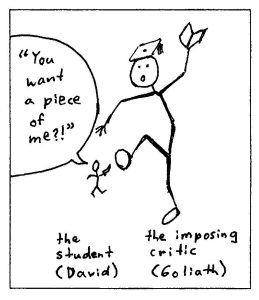

Strategy 1

Picking a Fight

Knock down a scholar’s argument and, in the best version of this strategy, replace it with one’s own. |

|

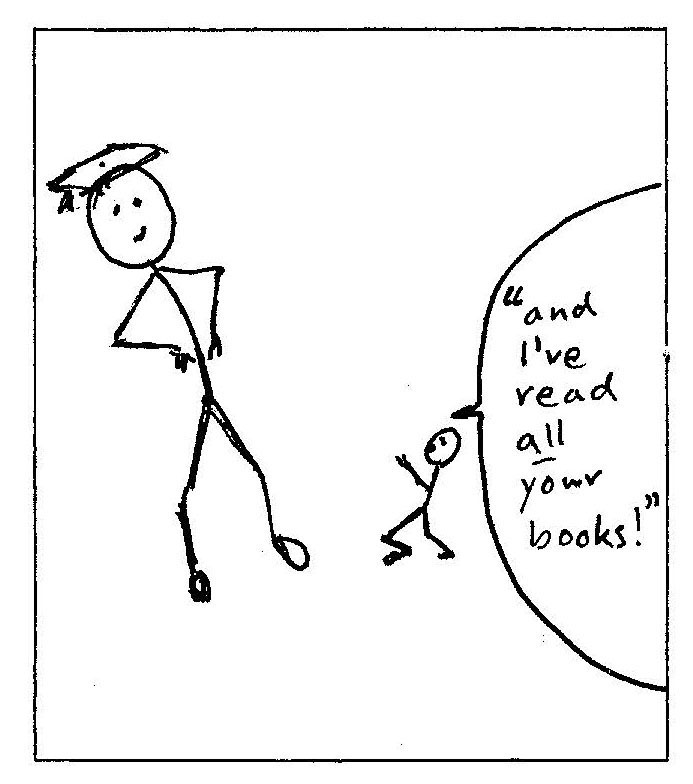

Strategy 2

Ass Kissing, or Riding a Scholar’s Coattails

Agree with a scholar to gain evidence and authority. Possibly go on to defend the scholar from attack by another scholar, thus resolving a larger controversy. |

|

Strategy 3

Piggybacking, or Standing on the Shoulders of a Giant

Agree with a scholar (i.e., kiss ass), but then complete or extend the scholar’s work, usually by borrowing an idea or concept from the scholar and developing it through application to a new subject or new part of the conversation. |

![Strategy 4: Leapfrogging: Step 1: a small stick figure holds the hand of a larger stick figure. A speech bubble above the small stick figure says "Gee you're swell! Let me shake your hand …". [a scuffle ensues] Step 2: the small stick figure stands on the shoulder of the larger stick figure. A speech bubble above the small stick figure says "…but I'll take over from here!".](https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/app/uploads/sites/231/2023/08/gaipa-strategy4-leapfrogging-260x300.jpg) |

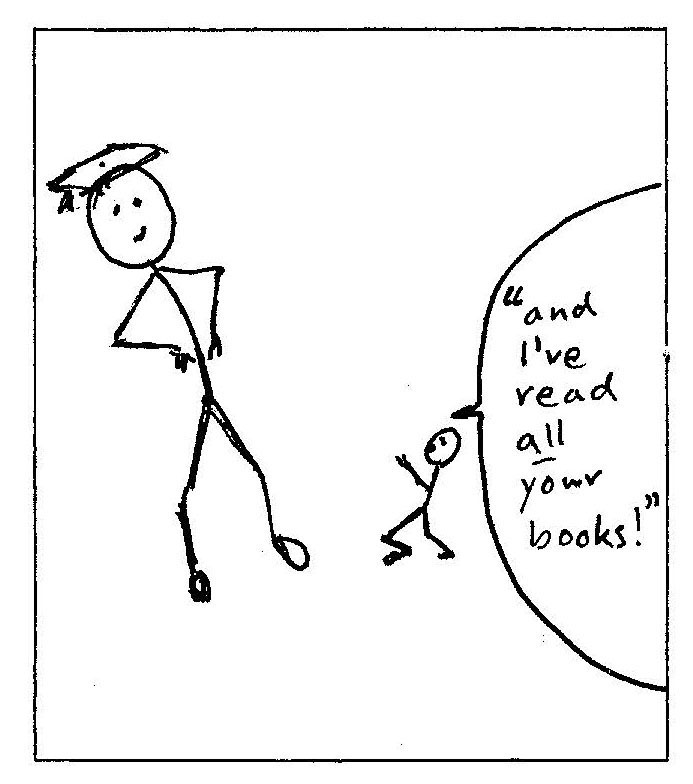

Strategy 4

Leapfrogging, or Biting the Hand That Feeds You

Agree with a scholar (i.e., kiss ass), then identify and solve a problem in the scholar’s work—for example, an oversight, inconsistency, or contradiction. |

|

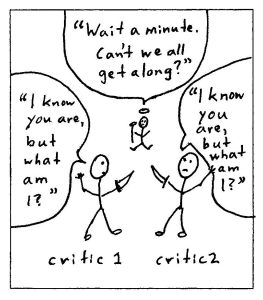

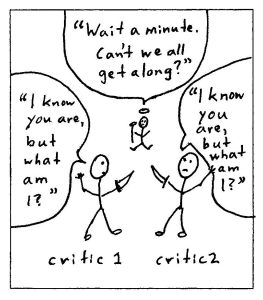

Strategy 5

Playing Peacemaker

Identify a conflict or dispute between two or more scholars, then resolve it using a new or more encompassing perspective. |

|

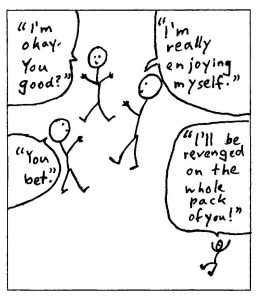

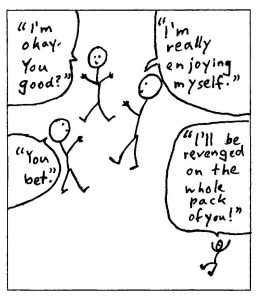

Strategy 6

Taking on the Establishment, or Acting Paranoid

Pick a fight with everyone in a critical conversation—for example, by showing how the status quo is wrong, a critical consensus is actually unfounded, or a dispute is based on a faulty assumption. |

|

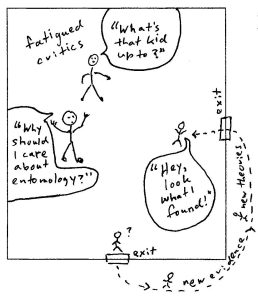

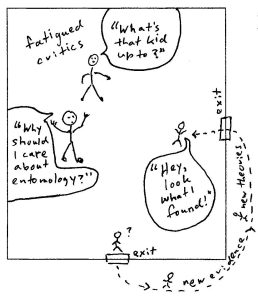

Strategy 7

Dropping Out, or Finding Room on the Margins

Focus on an issue in the margins of the critical conversation, illuminating that issue and (in the best version of this strategy) ultimately redefining the conversation itself. |

|

Strategy 8

Crossbreeding with Something New

Inject really new material into the critical conversation to produce a new argument. For example, bring in a theory from another discipline to reinterpret the evidence, bring in new evidence to upset an old theory or interpretation, or establish an original framework (a combination of theories, a historical understanding) to reinterpret the evidence. |

![Strategy 4: Leapfrogging: Step 1: a small stick figure holds the hand of a larger stick figure. A speech bubble above the small stick figure says "Gee you're swell! Let me shake your hand …". [a scuffle ensues] Step 2: the small stick figure stands on the shoulder of the larger stick figure. A speech bubble above the small stick figure says "…but I'll take over from here!".](https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/app/uploads/sites/231/2023/08/gaipa-strategy4-leapfrogging-260x300.jpg)