Visual Rhetoric and Communications

You may not realize it, but images make an argument, or maybe it seems obvious that they do. We use images in the form of memes to make arguments on social media all of the time. However, it may surprise you to learn that they do that in much the same way that text does.

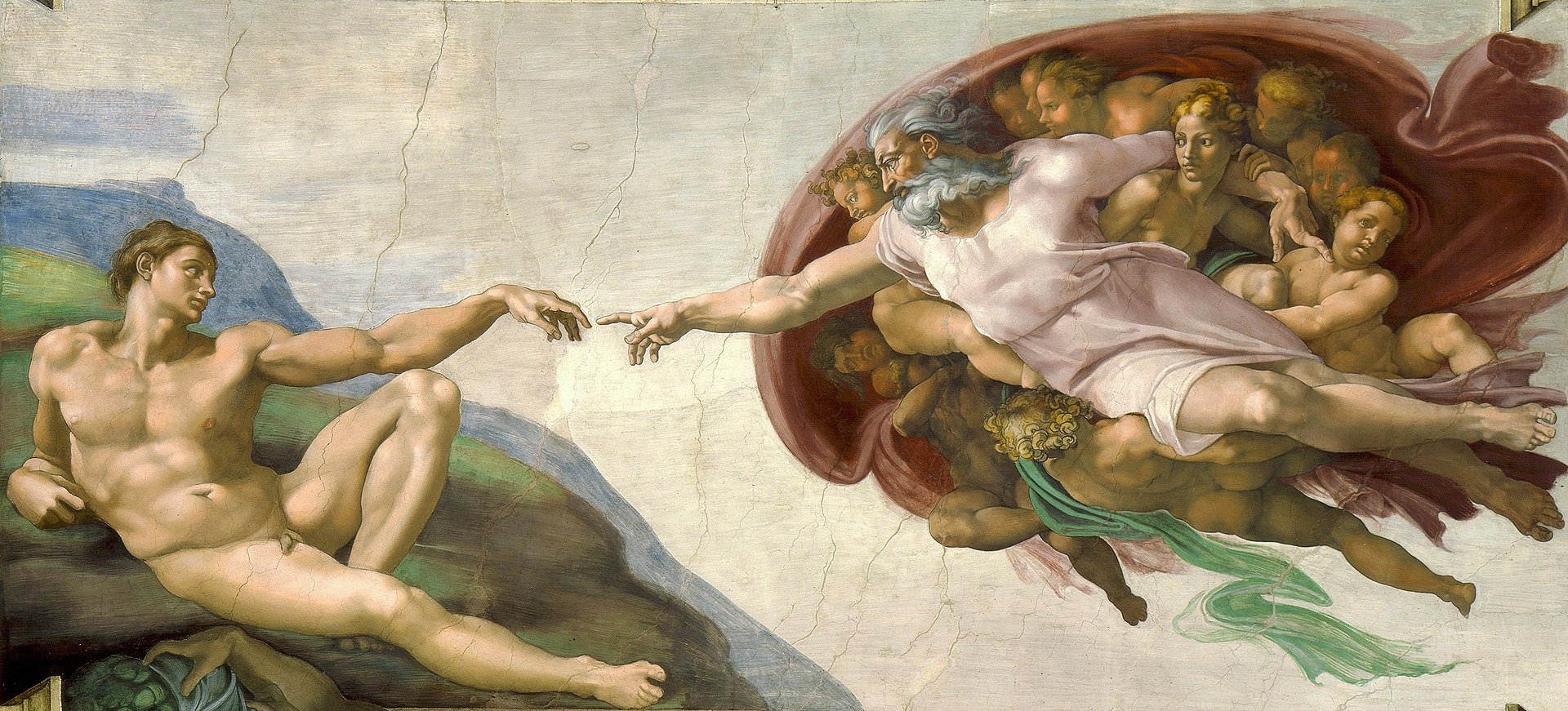

As with textual arguments, one of the most important things to consider is how the rhetoric of images will be perceived by our audience. In other words, what contextual references do we share with our audience? Here’s an example of a referent system. Our audience needs to know the painting on the right (Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam) in order to “get the joke” of the image of the cat.

So, how can we apply visual rhetoric using images in order to reinforce textual argument? How can we use visual media impact our audience?

These materials will help you to understand:

- Understand basic principles of visual communication.

- Define visual rhetoric as a strategy for argument.

- Identify the foundations of rhetoric and persuasion.

- Identify connections between textual and visual rhetoric.

Introduction to Visual Communications

Through learning about visual communications, you will discover a lot of similarities between the principles of formal writing and the principles of using visual media in purposeful communication because, ultimately, you will be communicating to an audience of humans – and humans have the same cognitive needs for information to form meaning no matter which medium is used.

Essentially, human brains are “pattern making machines” that rely on assembling bits and pieces of information into a coherent whole in order to make sense of a message. The human brain cannot bear having empty gaps of information and will often fill that gap with something, even if it is the wrong information. The human brain also dislikes ambiguity. The brain doesn’t just want messages to have meaning – it wants messages to mean something conclusive and for it to fit into one’s personal reality.

Humans are also very attuned to their personal identity, situations, attitudes, beliefs, values and expectations. When humans encounter messages, they interpret them according to their unique perceptions as well as from the influence of larger cultural, political, religious, or moral frameworks. This is why your messages will require considering more than your own personal point of view or context as a basis for communicating to an audience.

The value of this course will be in how you practice crafting coherent messages and narratives that serve your audience’s cognitive and humanistic needs so that you achieve your intended communication goal, whether in an academic environment or in professional practice.

In summary, everyone in this course has been a consumer (on the receiving end) of visual media. Your challenge in this course will be to go beyond being a consumer of visual media to becoming an effective and conscientious producer of visual media.

|

|

To achieve this, you will need to draw upon the following sets of foundation knowledge:

- Organizing Principles: Context, audience, and purpose.

- Rhetorical Strategies: Communications techniques used produce a particular effect on an audience.

- Use of Creative Commons resources: Locate images that are available for reuse under Creative Commons license and attribute them appropriately.

- Ethical use of imagery: Present imagery and graphical representations of information that do no mislead the audience or misrepresent reality.

- Narrative form and transition: Assemble individual messages and show connections between them so that it feels like a coherent whole to your audience.

The following video from the Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) describes the basic elements of Visual Rhetoric.

Visual Rhetoric

Visual rhetoric is a special area of academic study unto its own. It has a long history in the study of art and semiotics (the study of symbols) and it has kinship to the classical study of oral rhetoric such as persuasive speeches and legal arguments.

For the purpose of our studies, we will define the phrase “visual rhetoric” as the means by which visual imagery can be used to achieve a communication goal such as to influence people’s attitudes, opinions, and beliefs. The study of visual rhetoric, therefore, is to ask the question, “How do images act rhetorically upon viewers?” (Hill, C. A., & Helmers, M., 2012, p. 1).

The techniques of visual rhetoric align with the classic pillars of rhetoric:

- Ethos – An ethical appeal meant to convince an audience of the author’s credibility or character.

- Pathos – An emotional appeal meant to persuade an audience by appealing to their emotions.

- Logos – An appeal to logic meant to convince an audience by use of logic or reason.

One of today’s most familiar uses of visual rhetoric are the memes you see in social media. Memes, in an incredibly concise and penetrating way, are able to punctuate a dialogue or issue with “likes” and shares calculating a somewhat blunt measure of their popularity.

An example of a popular meme as documented by the KnowYourMeme.com website.

From KnowYourMeme.com: “Success Kid, sometimes known as I Hate Sandcastles, is a reaction image of a baby at a beach with a smug facial expression. It has been used in image macros to designate either success or frustration. In early 2011, the original image was turned into an advice animal style image macro with captions describing a situation that goes better than expected.”

© KnowYourMeme.com All Rights Reserved

So if memes are a common part of your daily communication, it is a good entry point for describing the capability of visual rhetoric.

Review

Purdue OWL: Visual Rhetoric Overview, which provides a graphical representation of visual rhetoric in relation to other disciplines plus some references to other research.

The American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) – Visual Rhetoric: An Introduction for Students of Visual Communication, which provides an overview of visual rhetoric as a body of knowledge within visual literacy and graphic design.

Linguistics: The Study of Language and Discourse

Language

Linguists study language in both its written and spoken form including its historical, cultural, anthropological, and political backgrounds. As described in the Introduction chapter, written language is produced in the form of a code (the alphabet). Words, as a code for a specific meaning in the dictionary, are often insufficient in conveying the intended meaning of a message unequivocally. If you have ever experienced the awkwardness of an email message or social media post that was misinterpreted by others in the worst possible way, you are familiar with this phenomenon.

The cause of this problem is rooted in the complexity of conveying a message in a medium that is too lean to punctuate how the message is to be interpreted. An example would be the difference between sending a letter to one’s beloved versus saying the same words in person. The beloved’s interpretation of the same message in the form of a letter could be different than if it were conveyed face-to-face even if the same words were used. The absence of non-verbal cues in the letter could cause a certain sarcastic or humorous passage to be errantly perceived as an insult.

Famed linguist Gregory Bateson (1968) described how a message is segmented into “content” and “relationship.” While the content could be described as the literal meaning of words as decoded by the lexicon of our language, the relationship portion of a message is the part that cues the receiver about how that message is to be taken as.

It is the author’s challenge to account for the audience’s need for both meaning and interpretation.

Discourse

We use language as the basis of human discourse, which is defined as “the production of knowledge through language” (Hall, 1997, p. 44). Hall’s inclusion of the word “production” supposes that knowledge is a process of human construction: As we communicate, we are constructing a shared sense of truth and reality while forming the contours of a social world. Our social world .”.. is the overall outcome of our joint processes of social – specifically, communicative – construction” (Couldry, N., 2018, p. 18).

As you construct messages through the use of oral, written, and visual media, you are, in essence, creating a shared understanding – a reality – through a social process communication.Visual Rhetoric in Practice

The traditional study of rhetoric, as the prior video describes, is the study of communication in the art of persuasion. The term visual rhetoric suggests that there is kinship with traditional oral rhetoric and written rhetoric, but in a different (visual) form.

For example, in the following print ad for Pinnacle Bank, the visual element has nothing to do with banking, but has everything to do with persuading the viewer that the bank has ethos, or credibility, with respect to the individuals or businesses they are appealing to. To the audience, the selection of a farm image is intended to recognize the audience’s perspective, interests, traditions, and livelihood so that it promotes feelings of trust, connection, and mutual understanding, even though the occupations of banker and farmer couldn’t be more different.

The Basics of Copyright, Fair Use, and Creative Commons

Understanding permissions and rights for images is essential to your academic integrity. Review this resource in order to understand how you will cite the images you include in your presentation.

https://granite.pressbooks.pub/comm543/chapter/the-basics-of-copyright-fair-use-and-creative-commons/

The content of this lesson is an Open Educational Resource with a Creative Commons license: Visual Communication(opens in a new tab) by Granite State College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License(opens in a new tab), except where otherwise noted.

Licenses and Attributions (in APA format)

Covell, S. (2022). Visual Communication: A General Education textbook for the study of visual rhetoric. Granite State College. https://granite.pressbooks.pub/comm543/(opens in a new tab)

References

Bateson, G. (1968). Information and codification: A philosophical approach. In J. Ruesch, & G. Bateson (Eds.), Communication: The social matrix of psychiatry (pp. 168–211). New York, NY: Norton.

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2018). The mediated construction of reality. John Wiley & Sons.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 15-64). London: SAGE Publications in association with The Open University.

Hill, C. A., & Helmers, M. (Eds.). (2012). Defining visual rhetorics. Routledge.