10 Speaking to Persuade/Advocacy

Gillian Bonanno, M.A.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- Define persuasion and advocacy.

- Explain the roles of ethos, pathos, and logos in persuasion.

- Choose a topic.

- Conduct research.

- Structure an outline.

- Use visual aids.

- Prepare for feedback.

Introduction

This chapter begins with a discussion of the elements of persuasion and advocacy, including the means of persuasion identified in Aristotle’s Rhetoric: ethos, pathos, and logos. The chapter also provides a guide to planning a persuasive presentation or speech. The conclusion of the chapter includes interviews with people who work as advocates in different fields.

Persuasion

Persuasion is “the act of influencing someone to do something or to change their mind” (“Persuasion”). In a persuasive presentation, the goal is to provide the audience with information that will convince them to see your side on an issue.

Six Principles for Persuasion

According to Cialdini and Goldstein, “the six basic principles that govern how one person might influence another are: liking, reciprocation, consistency, scarcity, social validation, and authority” (41). First, an individual may be more likely to be persuaded by someone whom they “like,” which ranges from knowing someone personally to having an “instant bond” with a stranger (Cialdini and Goldstein, 41). Reciprocation refers to the notion that there is an exchange of some kind, such as in business negotiations (Cialdini and Goldstein, 45). Consistency encourages individuals to persuade others by recognizing “a fundamental human tendency to be and to appear consistent with one’s actions, statements, and beliefs” (Cialdini and Goldstein, 45). Scarcity can be influential because “items and opportunities that are in short supply or unavailable tend to be more desirable than those . . . that are plentiful and more accessible” (Cialdini and Goldstein, 46). For example, think about a product that you may be interested in purchasing. If the product is limited in production or availability, it might persuade you to be more interested in purchasing the item. Social validation refers to the idea that individuals “look to others for cues,” and this will influence their decisions (Cialdini and Goldstein, 48). Finally, authority can be influential because individuals are persuaded by those they consider to have an expertise in a particular area (Cialdini and Goldstein, 49).

These six principles provide some examples of how an individual (or an audience) can be persuaded. There are certainly other methods; and note that not all these principles need to be included in a persuasive presentation for it to be effective.

Types of Claims

In addition to the principles listed above, you may consider choosing a basis, or claim, for formulating an argument. This chapter will address three types of persuasive speech claims: questions of fact, value, and policy. In general, according to Jim Marteni:

-

Claims of fact are quantifiable statements that focus on the accuracy, correctness or validity of such statements and can be verified using some objective evidence.

-

Claims of value are qualitative statements that focus on judgments made about the environment and invite comparisons.

-

Claims of policy are statements that focus on actions that should be taken to change the status quo.

Let’s explore each of these types of claim in more detail, starting with a discussion of statements of fact. A claim of fact is “something quantifiable has existed, does exist, or will exist” (Types of Claims). This type of claim focuses on data that may not necessarily be refutable based on quantitative data used to present your side of an issue. There are many examples of speeches that use statements of fact as a basis for an argument. The claim may stem from something that you do every day (such as brushing your teeth or taking a walk), but you may want to persuade the audience that they should also do these things if they are not already doing so. In these examples, you may state something specific and able to be verified such as, ‘Brushing your teeth teeth twice a day can decrease tooth decay’ or ‘Walking every day decreases risk of cardiovascular disease’ and then support these claims with clear statistics, charts, or data that will help them to embrace your claim. (Please note that the claims above are simply examples, and data is not included to support or refute these claims in this chapter.)

You may also wish to consider a speech that addresses a question of value. A claim of value “asserts qualitative judgments along a good-to-bad continuum relating to persons, events, and things in one’s environment” (Types of Claims). This type of speech may include more qualitative data, such as open ended responses. The claim of value may include words such as good, bad, better, best, or worse. These are often considered to be subjective terms (one person may have a different idea of good/bad/better/best/worst) and it is the responsibility of the presenter to define these subjective terms and also provide evidence to support the claims. Some examples might include ‘Car X is better than Car Y’ or ‘Coffee is the best morning beverage.’ (Note that these are simply examples, and support for these claims are not provided in this chapter.)

In a claim of policy, the word “should” helps to formulate your argument. Using the word “should” is important as it “implies that some action ought to be taken, but not that it must or will be taken” (Types of Claims).

You may use this type of claim to address issues of politics, policies, health, environment, safety, or other larger global concerns . Your speech will describe the reason why you feel that a policy or issue should (or should not) be addressed in a specific way based on your research. In this type of speech, you are asking your audience to support your solution to an issue that you have presented to them. Examples may include “Policy A should be changed to include (mention what should be included)” or “College students should have access to (mention what students should have access to).” Presenters for this type of speech should clearly explain the policy and then share with the audience why it should be changed (or upheld) by using their research to support the position.

Advocacy

Advocacy, on the other hand, is “the act or process of supporting a cause or proposal” (“Advocacy”). An advocate feels strongly about an issue and will work diligently to encourage others to support their cause. An advocate should be able to speak about an issue in a concise, professional, and persuasive manner. Enthusiasm for a cause will shine through if the advocate thoroughly embraces the role. This can be accomplished by conducting research, exploring opposing views on the issue at hand, preparing effective visual aids, and practicing the delivery of the content before a presentation or event. An advocate takes on many forms. A lawyer advocates for clients. A patient may advocate for rights to care. A student may advocate for a higher grade from a professor.

An advocate can be described as:

1) One who pleads the cause of another, specifically one who pleads the cause of another before a tribunal or judicial court.

2) One who defends or maintains a cause or proposal.

3) One who supports or promotes the interest of a cause or group (“Advocate”)

Types of Advocacy

There are many types of advocacy. This chapter will address self- advocacy, peer advocacy, and citizen advocacy.

Self- advocacy addresses the need for an individual to advocate for oneself. Examples might include negotiating with a boss for a raise, or perhaps used when applying for college or health insurance. According to an advocacy website, Advocacy: inclusion, empowerment and human rights, “The goal of self-advocacy is for people to decide what they want and to carry out plans to help them get it …. the individual self-assesses a situation or problem and then speaks for his or her own needs.”

Individuals who share experiences, values, or positions will join together in a group advocacy setting. This type of advocacy includes sharing ideas with one another and speaking collectively about issues. The groups “aim to influence public opinion, policy and service provision” and are often part of committees with varying “size, influence, and motive.” (Advocacy: inclusion, empowerment and human rights.) Examples might include groups interested in protecting the environment, rights to adequate health care, addressing issues of diversity, equity, and/or inclusion, or working together to save an endangered species.

A citizen advocate involves local community members who work together to have a platform to address issues that affect their lives. An example might include community school boards or participation in town hall meetings. (Advocacy: inclusion, empowerment and human rights)

As you can see, persuasion and advocacy have been defined in different ways. As the presenter, you have the opportunity to persuade your audience, and can use these definitions to help you decide what type of advocate or persuasive presentation that you would like to develop.

Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

Before we begin developing our speeches, let us take a moment to address Aristotle’s appeals for persuasion: ethos, logos, and pathos.

Ethos

What is ethos?

Ethos relates to the credibility of the speaker (Ethos). An audience member should feel as if they can trust the information provided by the speaker. When listening to a presenter, ask yourself:

- Does the speaker seem to have knowledge about the topic?

- Do you feel that this person is qualified to share information with you?

Using ethos as a tool for persuasion

As a presenter, you can let your audience experience your credibility in a few different ways. Using more than one of the methods below can certainly increase your credibility.

- Tell the audience directly. For example, you may wish to convince your audience to drink tea for breakfast. You can share something like, “My experience stems from a lifelong enjoyment of tea. I drink one cup each day and have tried a variety of types, so I feel that I can share with you some of my favorite types to try based on my personal experience.”

- Share quality research. For example, you may have visited the BMCC databases to gather information about types of tea, benefits of drinking tea, and information about individuals who drink tea. You may have also done some individual research (surveying classmates about their morning beverage preferences). These types of data will help to support your claim and help the audience to agree with your perspective.

- Acknowledge the perspective(s) of others. Perhaps your audience is full of individuals who prefer coffee, water, or nothing to drink in the morning, Acknowledging these different perspectives lets the audience know that while you may be knowledgeable about your chosen topic, you also understand that others may have a different (and also valued) opinion that differs from your own.

Pathos

What is pathos?

Pathos relates to the emotional appeal given to the audience by the presenter. This includes the language and presentation style of the presenter. It ties to your organizational style, your choice of words, and your overall stage presence. Some examples are: using vivid language to paint images in the minds of audience members, providing testimony (personal stories or stories relayed to you by others), and/or using figurative language such as metaphor, similes, and personification. A presenter can also use various vocal tools such as vocal variety and repetition to appeal to the audience on an emotional level. (Pathos. 2020)

Using pathos as a tool for persuasion

When you are describing drinking tea to your classmates, you can use words or phrases to encourage them to try it. You can tell them about its delicious aroma. You can also tell a story – perhaps having the audience members picture themselves getting up in the morning, making a nice cup of tea, holding it in their hands, and taking a moment enjoying the tea as they get ready to embrace the day!

An emotional appeal can also be used to gain sympathy from your audience. Think about commercials or advertisements that you may have seen, perhaps ones that encourage you to donate to an organization or to adopt an animal. These types of advertisements appeal to your emotions through their use of images, music, and/or detailed stories.

Logos

What is logos?

Logos ties to both reasoning and logic of an argument. Speakers appeal to logos “by presenting factual, objective information that serves as reasons to support the argument; presenting a sufficient amount of relevant examples to support a proposition; deriving conclusions from known information; and using credible supporting material like expert testimony, definitions, statistics, and literal or historical analogies.” (Logos, 2020)

Using logos as a tool for persuasion

Logos relates to using the data collected to form a reasonable argument for why your audience members should agree with the speaker. After you have collected your data, you must now create an argument that will potentially persuade your audience. If we continue with our persuasive speech directed at drinking tea in the morning, you might find an article that relates to college students who drink tea. Using valid reasoning is key! Take some time to ensure that your argument is logical and well-organized. A logical, well-structured argument will help to persuade your audience.

Now that we have learned some foundational concepts related to persuasion, let us move to a discussion of choosing a topic for a persuasive speech.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

Now that we have explored some definitions of persuasion and advocacy, let us move on to choosing the topic that you will be presenting to your audience. When picking a topic, you may consider choosing something that you are passionate about and/or something that you want to know more about. Take a moment to consider topics that we would like to share with your audience. Individuals have different experiences and perspectives on varying issues. Sharing your perspective on a topic is what can make your presentation unique and exciting to the audience.

When looking for a topic, cause, or issue to discuss, consider asking yourself the following questions (also located in worksheets):

- What is important to me?

- What excites me?

- What makes me happy?

- What makes me angry?

- Do I have a good idea that others might embrace?

- Is there an issue that ‘speaks’ to me?

- Can I make a change?

- Have I experienced something inspiring or life-changing that I can share with others?

Here are some additional ideas to consider when choosing a topic:

- Choose a topic that is (relatively) new to you! You may consider taking some time to explore a topic that you do not yet know about and/or one that you want to learn more about. Perhaps you recently read, saw, or experienced something that you would like to research and share with your audience. Maybe you began your process with not knowing which side you support on an issue, and you take some time to research both sides of an issue and determine which you support. You can use this presentation as an opportunity to learn more about that topic and can then talk about this process in your presentation. Using the research that you have gathered will help you as you explain to the audience why they should share your perspective on the item at hand.

- Choose a topic that you already know about and feel strongly that your audience should share your views on this topic. For this type of presentation, you will be taking your knowledge and expanding it. You can search for items that support your side and also take some time to review the data provided by those that support the opposite side of the issue.

Conducting Research

Research can be fun! In an earlier chapter you read about how to conduct research using the college library. Please reread that chapter again closely to help you conduct research to get data to build your persuasive speech. If you are able to accumulate data from a variety of sources, this will help you to persuade your audience members to share your passion about the topic at hand.

Some things may be easier than others to convince your audience to agree upon and others may be more challenging. If, for example, you want to encourage your classmates to exercise, it is important to consider the current exercise levels of your classmates. Ultimately, you would like each audience member to feel involved in your presentation, so you may wish to provide various suggestions.

For example, some members of the class may not currently exercise for a variety of reasons, so you may suggest that they try to incorporate 5-10 minutes of light activity 1-3 times a week. For classmates who are exercising once a week or more, you may encourage them to increase their exercise by one extra day per week. Finally, a group that may be currently exercising daily, you may wish to suggest adding a new type of exercise to their routine.

Structuring an Outline

There are many ways to structure a speech, and this chapter will offer one suggestion that may work well as you work to advocate for a cause or attempt to persuade your audience. A blank sample outline is located in the worksheet section of this chapter/book that can be used when you are preparing your speech. The length/time allotted for delivery of your presentation will be provided to you by your instructor, but let’s consider the speech in three general parts: Introduction, Body, and Conclusion. Between each section of the presentation, one should consider including a transition to let the audience member know that the speaker is moving on to the next segment of the presentation. Transitional devices are “words or phrases that help carry a thought from one sentence to another, from one idea to another, or from one paragraph to another…. transitional devices link sentences and paragraphs together smoothly so that there are no abrupt jumps or breaks between ideas” (Purdue Writing Lab Transitional Devices // Purdue Writing Lab).

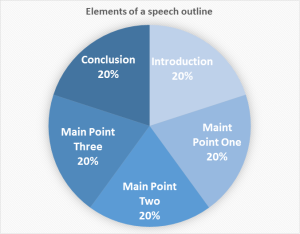

If the speech requirement is 4-6 minutes long, below is one way to consider timing the different sections of the presentation: One minute for the introduction, one minute for each main point, and one minute for the conclusion. This will be a roughly 5 minute speech, with a minute to spare for transitions. Here is a diagram to provide a visual guide to the elements of your outline. Start at the introduction and make your way clockwise around the image:

|

Introduction Includes attention getter, thesis statement, credibility, and preview of main points 1/5 of the presentation. |

|

Body Three main points – WHAT, WHY, and HOW. 3/5 of the presentation. |

|

Conclusion Includes restatement of thesis, review of main points, and powerful ending. 1/5 of the presentation. |

In the body of your presentation, you will formulate your argument in WHAT, WHY and HOW. Each area is equally important, so let’s take a moment to discuss the details of each part.

Let’s start with WHAT.

What does the listener need to know about your topic? If you are passionate about a topic or cause, remember that your audience may have a range of knowledge about the topic. Setting a strong foundation in the beginning of your speech will help the audience members to understand your speech. Remember, the amount of information that you include here will depend on the amount of time allotted by the instructor. You may wish to clarify by letting your audience members know that there are many things that you can tell them about the topic, but your presentation is going to focus on (insert your focus here).

Now, WHY does your audience need to feel the same way you do about this topic?

The first section of your presentation has provided the foundation for your listeners. The second section will be your opportunity to tell your audience why they should share your perspective on the issue. Provide them with details, including facts, images, stories, and/or statistics that will help them embrace your side of the issue.

Finally, HOW can the audience members act upon what you have told them?

Overall, for an individual to make a change, the person will need information and a way to use the information. If the audience is provided with the tools needed to make a change, they may be more likely to make the change. Sounds simple, right? It certainly can be, if you have conducted sound research and organized it in a way to reach your listeners. Refer to the sample speech outlines in the appendices of this book.

Visual Aids

Think about something that you saw recently that caught your eye. It may have been an advertisement on the subway, something you saw on a social media page, or anything else that you remember. Visual aids can certainly assist in connecting with your audience.

When you are designing your presentation, you may wish to consider including images, video clips, charts, and other visual media types to capture the attention of your audience. Think about what you want the audience to gather from your image. Where will you include the image? What will you say about this image? You may wish to discuss these images with your classmates and/or your professor to gain some feedback on the chosen visual aid(s). This will help you in selecting items that work most effectively in your presentation.

Here are two of the prototypes:

Above, the author thought it might be visually appealing to put the pieces of the speech outline in this arrowed path format. The feedback received was not positive, mostly “what is that?” “I don’t get it” and the like.

The point is: while all of your ideas and images may not be the final versions that you choose, it can be fun to experiment, and asking for feedback may help you to fine tune your work, or even spark an idea or image that you had not previously considered. The author truly enjoyed designing these graphs, and at the end of the day chose the one that the author felt would be best suited for the chapter based on the feedback received.

Preparing for Feedback

Turning to feedback, now that you have completed your speech, it will now be time to interact with your audience. Some audience members may respond to your presentation with questions. If you have inspired your audience, they may want additional information, or may even want to talk further about your presentation. Others may disagree with your speech and respond to your presentation with hostility or frustration. Remember, you are in charge of addressing the audience members, and, as such, you must formulate a strategy for handling feedback. Your instructor may also set some guidelines for expectations for question and answer segment(s) for your presentation.

Here are some questions that you may wish to ask yourself as you prepare to address feedback:

- Have I addressed the other side of the issue discussed in my speech?

- What will I do if someone gets angry with me?

- What questions might my audience have for me?

- Have I used quality sources to prove my points?

- Can I explain any charts or graphs that I have presented?

- If the audience members want to know more about my cause, what information will I provide to them?

Ready to Begin: Inspiration

Now it is your turn to persuade your audience. Be the advocate! Share your knowledge and passion with your classmates. Use this chapter, the worksheets, and your own talents to help you with the process of writing, researching, outlining, and presenting. Take your time with each step and enjoy the process. Below are some voices of advocates discussing what they do and why they do it. Perhaps these stories will inspire you as you work! Survey data collected via surveymonkey.com, and some names have been changed.

Melissa S., Cystic Fibrosis Advocate

What does the term “advocate” mean to you?

Sharing your story to educate and inspire in order to further your cause.

How did you become an advocate?

I was asked to formally advocate for an organization, but in truth, I advocate for myself or my family or issues I believe in.

What do you advocate for?

I advocate for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation on behalf of families who endure life with Cystic Fibrosis (CF). I advocate for policy change that betters the lives of CF families with issues surrounding disability and bettering research methods, as well as funding (from various agencies) so that research can be conducted in the most efficient, expedited, and safe fashion.

Why is it so important to advocate for your cause?

It is important because I have Cystic Fibrosis and have also lost a brother to Cystic Fibrosis. I wasn’t to ensure that my family doesn’t suffer another loss that no family should suffer.

What advice can you give others who are looking to become an advocate?

It can seem intimidating to stand in front of a group of people to advocate for your cause, but the truth is that your story, and why you’re advocating is THE most important part of it. Don’t get bogged down or scared about memorizing facts and figures – the best thing someone can take away from talking with you is the visceral reaction they get from hearing how your issue affects you and your family.

In a few sentences, describe yourself.

I am (a) decidedly optimistic person who lives with a debilitating progressive disease (Cystic Fibrosis). While having CF occupies a lot of time in my daily life, I try not to let it define me and live my life with joy and purpose. I love my family and friends and will do anything in my power to protect them. I also love standing up for things I believe in. Becoming an advocate for CF has lifted my voice and given me the confidence to speak out. Now, I can’t stop! (updated 7/2021).

D. D., Registered Nurse

What does the term “advocate” mean to you?

Advocate means to support or fight for a cause.

How did you become an advocate?

I became an advocate since working within the medical field and because I am a mother.

What do you advocate for?

I am an advocate for my son. He is an alcoholic and drug addict. I am involved with helping addicts and families that are in need of support and guidance. I am a volunteer for (a) local YMCA to help bring a face to the disease of addiction. I am also an advocate for people with Cystic Fibrosis. I am a Registered Nurse who has been caring for patients and families affected by this disease. I am there for medical, emotional and fundraising support.

Why is it so important to advocate for your cause?

It is important for me to put a face to the families that are suffering from these diseases. To make it more personal.

What advice can you give others who are looking to become an advocate?

Be strong and vigilant. Really believe in what you are supporting. Passion goes a long way.

In a few sentences, describe yourself.

I am a mom and an RN. I am a recent widow with 2 children who have had their struggles but are now doing well. I work full time as a Nurse Manager at NY hospital.

Is there anything else that you would like to share? A story, perhaps, about a time that you felt very strongly about something, and what you did to advocate for that person or cause?

Every day I feel like I advocate for addiction. Many people do not realize addiction affects everyone. I constantly have to remind people that I meet of this. It is difficult at times because most people have the most horrible things to say about addicts. I try to educate people about addiction as much as I can.

C. B., Breast Cancer Survivor

What does the term “advocate” mean to you?

Supporter of something you are passionate about and believe in.

How did you become an advocate?

I became an advocate of breast cancer through my own experience.

What do you advocate for?

I am an advocate for breast cancer! This disease generally affects women but in some cases men are also affected! It is a silent beast that can creep up on you at any time in your life… it has no discrimination and age is not a factor.

Why is it so important to advocate for your cause?

It is simple… it is the difference between life and death! So many women are so afraid they choose to ignore the signs. It is so important to find your strength, face your fears and deal with this head on!!!

What advice can you give others who are looking to become an advocate?

Speak your truth! Tell your story! You have no idea how much it can help someone else who is facing the very same fears!

In a few sentences, describe yourself.

I have always believed where there is a will, there is a way! I never take no for an answer when it is something really important that matters! It is one of my earliest mottos I have followed through life. I have always been determined to find my strength and face my fears even on my darkest day!!!

Is there anything else that you would like to share? A story, perhaps, about a time that you felt very strongly about something, and what you did to advocate for that person or cause?

I feel it is so important to help women face their fears when it comes to breast cancer. It is for this reason so many do not examine themselves and/or go for mammograms. I can tell you first hand every moment counts!!!! I did one whole year of chemotherapy, lost my beautiful hair but fared through! Again I was LUCKY!! I can only hope that this will help others facing breast cancer!

Review Questions

- Define Ethos, Pathos and Logos.

- What are three types of persuasive claims listed in this chapter?

- What are the three types of advocacy listed in this chapter?

Works Cited

“Advocacy.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/advocacy. Accessed 2 Jul. 2021.

“Advocacy: Inclusion, Empowerment and Human Rights.” Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), Updated Oct. 2020, www.scie.org.uk/care-act-2014/advocacy-services/commissioning-independent-advocacy/inclusion-empowerment-human-rights/types.asp.

“Advocate.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/advocate.

Bonanno, G. “What does it mean to be an advocate?” Survey. November 2016.

Cialdini, Robert B., and Noah J. Goldstein. “The Science and Practice of Persuasion.” The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 2, 2002, pp. 40–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8804(02)80030-1.

“Persuasion.” Vocabulary.com Dictionary, Vocabulary.com, https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/persuasion.

Purdue Writing Lab. “Transitional Devices // Purdue Writing Lab.” Purdue Writing Lab, 2018, owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechanics/transitions_and_transitional_devices/transitional_devices.html#:~:text=Transitional%20devices%20are%20words%20or,jumps%20or%20breaks%20between%20ideas.

Marteni, Jim. “Types of Claims.” Social Science LibreTexts. Los Angeles Valley College, 3 Dec. 2020, https://socialsci.libretexts.org/@go/page/67166.

the act of influencing other people either to believe something or to do something, or both

an assertion; the basis of an argument