9 Informative Speaking

Vincent (Tzu-Wen) Cheng, Ph.D.

Learning Objectives

- Define and identify informative speeches.

- Explain and analyze the general criteria for a good informative speech.

- Describe and list the major categories of informative speeches.

- Describe and explain the special considerations to be given in the informative speech-making process.

- Apply informative speech-related knowledge and skills into the development, presentation, and assessment of informative speeches.

“I cannot tell the truth about anything unless I confess being a student, growing and learning something new every day. The more I learn, the clearer my view of the world becomes.”

–Sonia Sanchez https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonia_Sanchez

The inspiring quote above from Sonia Sanchez, a US-American poet, playwright, professor, and activist who emerged out of the Black Arts Movement in the 1960’s (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Arts_Movement), beautifully captures how we as a species and individuals may strive to develop and build knowledge/skills throughout our lifetime for a better self and a better world—by recognizing our own limitations as human beings and by learning something new every single day.

Do you know the main source and driving force of this daily process of renewing ourselves? It is the information that intrigues, captivates, enlightens, and/or educates us; the information that we consume and share through informative speaking.

As you read this chapter, you will see many Wikipedia links/articles embedded throughout its texts and passages. While these Wikipedia links/articles are included to help you explore as you wish additional context to the subjects and concepts discussed, please be advised that there are limitations to these links/articles and they should be used only as a starting point for you to conduct more in-depth research elsewhere. A detailed discussion on Wikipedia’s strengths and limitations as well as the proper and ethical ways to use Wikipedia links/articles can be found later in this chapter.

As you read this chapter, you will see many Wikipedia links/articles embedded throughout its texts and passages. While these Wikipedia links/articles are included to help you explore as you wish additional context to the subjects and concepts discussed, please be advised that there are limitations to these links/articles and they should be used only as a starting point for you to conduct more in-depth research elsewhere. A detailed discussion on Wikipedia’s strengths and limitations as well as the proper and ethical ways to use Wikipedia links/articles can be found later in this chapter.

What is informative speaking or an informative speech?

The main goals of informative speaking or an informative speech are to describe, demonstrate, and/or explain certain information to our audience members by telling, teaching, instructing, updating, and/or notifying them as a reporter and/or educator.

Important to note…

The main goals of informative speaking or an informative speech are categorically different from the main goals of persuasive speaking or a persuasive speech which are to convince, compel, and/or influence our audience members by challenging, changing, urging, imploring, and/or affirming them as a champion and/or advocate. Refer to the chapter “Speaking to Persuade/Advocacy” for information on persuasive speaking.

A key element of informative speaking or an informative speech is neutrality. Informative speakers should be fair and balanced without choosing a side or taking a stance while imparting information. They should also let audience members come to their own conclusions about the information imparted without trying to influence them.

For example, when giving an informative speech on the Korean popular music (K-Pop) group BTS (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BTS), an informative speaker should strive to present it neutrally by including both positive and negative information found in research about BTS rather than sharing only favorable information about them from the perspective of an adoring fan (e.g., a BTS ARMY https://time.com/5912998/bts-army/).

Similarly, when developing an informative speech on caffeine, an informative speaker might want to discuss the effects of caffeine found in research neutrally (both positive and negative) rather than focusing only on either the dangers or the benefits of caffeine.

In addition, neutrality relates to the way in which a statement is made. For example, your friend A in a conversation makes the following statement:

“The film Roma [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roma_(2018_film)] directed by Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón is wonderful; you should see it!”

Here, A is not neutral nor speaking informatively since the statement is a persuasive one that expresses A’s positive assessment of the film and A’s clear intention to influence you. Let’s say later you tell your friend B that, “According to A, the film Roma is wonderful, and I should see it!” Here, you are speaking informatively since your statement neutrally describes the content of a previous persuasive statement from A; whether Roma is a wonderful film and whether you should see it are debatable and a matter of personal opinion, but what you share with B about A’s statement is undoubtedly factual, neutral, and informative.

At this point you might wonder—since neutrality is a key element of informative speaking, does that mean you can’t discuss controversial topics?

No, it doesn’t. No matter how controversial a topic is, there are ways to talk about it neutrally as an informative speech.

For example, we all know that abortion is a very controversial topic/issue over which we are still debating as a country and as a society. Can one develop an informative speech under the general topic of abortion? It certainly can be done as long as neutrality is observed and maintained.

A speech on how abortion laws have evolved in the United States and/or internationally over the years can be an informative speech, as long as it is designed to neutrally demonstrate and explain the who, what, when, where, why, and how (i.e., The Six W’s The “6 W’s” Method – Public Speaking & Speech Resources – Library at Windward Community College (hawaii.edu)) associated with abortion law changes without arguing whether these changes are good or bad, right or wrong, ethical or unethical.

Similarly, a speech on the two major camps currently involved in the abortion debates and their respective main arguments can be an informative speech, as long as both sides are presented neutrally without arguing whether one particular side and its key arguments are better or worse, right or wrong, ethical or unethical.

Some might argue that it is impossible to be absolutely objective and neutral as an informative speaker since the way we think and the way we speak are all influenced by our own unique experiences and subjective perceptions—in a way, we are already being subjective and biased by simply selecting the points we want to include in our presentation, however neutral they might be, and interpreting the information based on our own frame of reference.

Having said that, just because we don’t have access to an absolutely germ-free or virus-free environment for a surgery doesn’t mean that we should perform it without even sanitizing or disinfecting the instruments; there are things we can still do to make the surgery safer. Similarly, while it might be impossible for us to attain absolute neutrality as an informative speaker, we can still strive to make our information and presentation as neutral as possible.

Criteria for a Good Informative Speech

If neutrality is the key to make a statement/speech an informative one, what are the criteria for an informative speech to be considered good? They can be summed up as the CIA’s of a good informative speech; an informative speech must be clear, interesting, and accurate all at once to be good.

Be Clear.

“In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power.”

–Yuval Noah Harari, an Israeli public intellectual, historian, and professor https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuval_Noah_Harari

In order for our audience to be able to understand us when listening to our informative speeches, we as informative speakers must treat our information and presentation with care and make them as clear as possible.

Other than making sure that our informative speeches are clearly presented through the use of structured organization, visual aids, clear language, and effective nonverbal delivery (e.g., gestures, volume, articulation, and fluency), all of which are discussed in more detail in other chapters of this textbook, here are three additional guidelines we should pay special attention to as informative speakers:

Make our information more concrete and less abstract.

Abstract information tends to be more vague, ambiguous, and/or undefined; it is thus harder to process for any audience. The more abstract our information is, the harder it will be for our audience to listen to, grasp, and retain. Therefore, it is up to us as informative speakers to make any information we would like to impart in our presentation as concrete as possible.

How? By defining, describing and illustrating abstract information through the use of examples that our audience already has the frame of reference to understand.

For example, reciprocity as a concept, as an ethical principle, moral virtue, and/or social norm can be rather abstract for our audience to process. According to the Webster-Merriam Dictionary, “reciprocity” is defined as “the quality or state of being reciprocal: mutual dependence, action, or influence.”

In his book The Art of Public Speaking, Steven Lucas defines frame of reference as “the sum of a person’s knowledge, experience, goals, values, and attitudes. No two people can have exactly the same frame of reference.” As previously discussed in the chapter entitled “The Importance of Public Speaking,” in order for there to be mutual understanding and shared meaning between the sender and the receiver in a communication process, their sender’s frame of reference needs to overlap with the receiver’s frame of reference.

In his book The Art of Public Speaking, Steven Lucas defines frame of reference as “the sum of a person’s knowledge, experience, goals, values, and attitudes. No two people can have exactly the same frame of reference.” As previously discussed in the chapter entitled “The Importance of Public Speaking,” in order for there to be mutual understanding and shared meaning between the sender and the receiver in a communication process, their sender’s frame of reference needs to overlap with the receiver’s frame of reference.To make it more concrete, we may want to tap into our audience’s frame of reference and define/describe reciprocity by comparing it with, and highlighting its similarities to, other abstract concepts already known to our audience such as:

- Karma

- “What comes around goes around.”

- “As you sow, so shall you reap.”

- The Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you (treat others the way you want to be treated).

Other than using comparisons to highlight reciprocity’s similarities to more well-known abstract concepts, we can also make it more concrete by contrasting it with, and highlighting its differences from, other abstract concepts already known to our audience such as:

- “It’s my way or the highway.”

- one-sided love/crush or unrequited love/crush, and/or

- narcissism/narcissistic personality disorder (NPA).

Another way to make it more concrete is to tap into our audience’s frame of reference and illustrate reciprocity by using concrete and relatable examples such as:

Example 1: A volunteer working in at a street fair for a non-profit organization whose mission is to improve the COVID-19 vaccination rates for underserved/minoritized communities offers free gifts and a $100 vaccination incentive to unvaccinated fair attendees with the hope that that they will return the favor by getting themselves fully vaccinated.

Example 2: Student A is a native speaker of English and is in the process of learning how to speak Spanish more fluently. Student B is a native speaker of Spanish and is in the process of learning how to speak English more fluently. Through a language exchange program, they have been meeting regularly to discuss current events by using only Spanish during the first half of the meeting and only English during the second half.

Make our information more accessible, more user-friendly, and less technical.

Technical information tends to be more incomprehensible, unrelatable, alienating, and/or challenging. The more technical our information is, the harder it will be for our audience to listen to, grasp, and retain. Therefore, it is up to us as informative speakers to choose a subject matter that is not too technical and explain it in a more accessible and user-friendly language.

How can we make our information more accessible and user friendly? By avoiding jargon and by using examples and analogies that our audience already has the frame of reference to understand.

According to the Webster-Merriam Dictionary, “jargon” is defined as “the technical terminology or characteristic idiom of a special activity or group.” Consisting mostly of unfamiliar terms, abstract words, non-existent words, acronyms, abbreviations, and/or euphemism, jargon is the language of special expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand.

According to the Webster-Merriam Dictionary, “jargon” is defined as “the technical terminology or characteristic idiom of a special activity or group.” Consisting mostly of unfamiliar terms, abstract words, non-existent words, acronyms, abbreviations, and/or euphemism, jargon is the language of special expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand.For example, a computer motherboard as a subject matter might be rather technical for our listeners, especially those who are not computer savvy, to comprehend and feel eager to learn. Instead of using jargon such as CPU Socket, DRAM Memories Slots, and PCI Slots to discuss its main components, an informative speaker might want to use the human body as an analogy to describe/illustrate a motherboard and its various components.

More specifically, a motherboard is like our nervous system—it is where all computer parts are connected to each other and through which all electrical signals are conducted.

A hard drive on a motherboard is like the hippocampus region of our brain dealing with long-term memory—it is where all programs, files, and data are stored.

On the other hand, a motherboard’s DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) slots are like the Prefrontal Cortex of our brain dealing with short-term memory—it is a holding area of files and instructions that are to be used and then forgotten about; the more DRAM our computer has, the better and faster it can multi-task and perform.

A CPU (Central Processing Unit) chip on a motherboard is like our spinal cord—it is responsible for processing instructions (commands) received from the hard drive (brain).

Avoid overestimating what our audience knows.

A huge part of audience analysis and adaptation as an informative speaker is to properly gauge how much our audience already knows about our topic (see the chapter entitled “Andiene Analysis” for more details). If we overestimate what our audience knows and impart information completely outside of their frame of reference (see diagram below), they will feel totally lost and find our information frustratingly unclear.

Let’s say you collect and trade sneakers as a hobby. After brainstorming a few possible topics for your informative speech, you decided to build on what you already know and develop an informative speech on the co-culture of sneaker collecting (or sneakerheads https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sneaker_collecting).

Assuming that all your audience members either have heard of or already know something about this particular co-culture, you focused your presentation on the major brand identities, trading platforms, as well as potential benefits and risk factors associated with collecting sneakers while using lingo (similar to jargon discussed earlier on page 6) such as Bred, Hypebeast, Grail, and DS/Deadstock (https://www.farfetch.com/style-guide/how-to/sneaker-terms-urban-dictionary/) commonly used by sneakerheads throughout your presentation without any explanations. It turns out that many of your audience members have never even heard of this co-culture called sneakerheads and thus have no frame of reference to clearly understand/follow your information/presentation. This outcome is very unfortunate and is something an informative speaker should strive to avoid.

Be Interesting.

“That is what learning is. You suddenly understand something you’ve understood all your life, but in a new way.”

Doris Lessing, a British-Zimbabwean novelist who was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doris_Lessing

Other than making sure that our informative speeches are interestingly presented through the use of visual aids, vivid language, and effective nonverbal delivery (e.g., gestures, facial expressions, and vocal varieties), all of which are discussed in more detail in other chapters of this textbook, here are four additional guidelines we should pay special attention to as informative speakers:In order for our audience to be able to not only clearly understand us but also learn something relatable and new from us when listening to our informative speeches, we as informative speakers must treat our information and presentation with love and make them as interesting as possible.

Always bring something new to the table.

Nothing motivates our audience members to listen to and engage with our informative speeches more than the anticipation that our information might educate and enrich them in such a way that they transform themselves. It thus behooves us as informative speakers to avoid the same old, same old and always bring something new to the table when we present our information. The last thing we want is for our audience members to find our information and presentation boring, predictable, uninspiring, and a waste of their time.

Information-wise, we as informative speakers should find creative and innovative ways to open eyes, provoke thoughts, and expand horizons every step of the way, including selecting a suitable topic, locating credible supporting materials through research, organizing information in the speech body, as well as designing effective speech introduction and conclusion.

Certain informative speech topics (e.g., cigarettes, condoms, marijuana, or recycling) are so commonplace and overused that they have become rather clichéd. As informative speakers, we might want to consider taking our audience on a journey less travelled by others with our presentation and staying away from these overused topics. This does not mean that it is impossible to create a good informative speech on one of these overused topics; it just means that an overused topic especially needs creativity and innovation to keep its information interesting.

For example, if you want to develop a cigarette-related informative speech, instead of focusing your presentation on well-known common-sense facts (e.g., its ingredients and health effects), you might want to bring less-known facts and cutting-edge technologies and/or new developments and phenomena in the tobacco industry to your audience’s attention.

Even with an informative topic that is not too commonplace or overused, there are also ways for us as informative speakers to make it even more interesting by finding through our research and including in our presentation some topic-related historical, political, economic, social, and/or cultural discoveries, perspectives, insights, analyses, and applications that are new to our audience.

For example, if you want to develop a Carnival-related informative speech, instead of focusing your presentation only on the usual suspects (e.g., its masks, costumes, music, and dance), you might want to offer your audience some fresh new perspectives on Carnival as well (e.g., why/how it takes on very different forms around the world or even just among different islands in the Caribbean? What are the impacts of colonialism and imperialism on the celebration of Carnivals in different countries? How Carnival culture has manifested itself in popular culture?)

Presentation-wise, an informative speaker may keep an audience interested by using the following nonverbal strategies (all of which are discussed in detail in other chapters):

-

- Use vocal varieties in pitch, volume, tone, pace, pause, intensity, inflection, and accent.

- Employ engaging gestures, facial expression, and eye contact.

- Provide dynamic presentation aids such as overhead projection, slides, electronic whiteboards, video conferencing, and multimedia tools.

Avoid underestimating what our audience knows.

Whereas overestimating what our audience knows as an informative speaker and imparting information outside of their frame of reference, as discussed earlier on page 7, will make our information unclear and hard to comprehend, underestimating what our audience knows and imparting information completely inside of their frame of reference (see diagram below) will make our information uninteresting and uninspiring. In this instance, while our audience might be able to easily and readily understand every single piece of information imparted in our presentation, they will find our speech boring, redundant, unsatisfying, and a waste of their time.

Let’s say you enjoy and spend a lot of time on social media. After brainstorming a few possible topics for your informative speech, you decided to build on what you already know and develop an informative speech on one of the major social media platforms called X.

Assuming that all your audience members either have never heard of or know very little about this particular social media platform, you include in your presentation only basic information on its history, users, and major features. It turns out that most of your audience members are avid users of X themselves; they feel disappointed by the rudimentary information provided in the presentation and wish they had learned something new from it. This outcome is very unfortunate and is something an informative speaker should strive to avoid.

Relate the subject and information of our speech directly to our audience.

One major challenge for us as informative speakers to recognize and overcome is that what is interesting to us may not be interesting to everybody. Rather than developing and presenting an informative speech that only we find interesting, we must take it upon ourselves to make our speech something our audience members will find interesting as well by relating its subject and information directly to them; the more our audience members find our speech relatable, the more interesting it is to them.

For example, if you plan to develop and present an informative speech on the five pillars of Islam (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_Pillars_of_Islam), in addition to defining, describing, and explaining them from a Muslim perspective, you might want to consider comparing and contrasting them with concepts/perspectives from other major religions and/or other non-religious ethical principles around the world to which your non-Muslim audience can easily relate.

More specifically, when developing an informative speech on the five pillars of Islam, you might want to consider comparing and contrasting:

- the pillar of Shahada (profession of faith) with confirmation (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confirmation) and adult baptism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Believer%27s_baptism) in Christianity;

- the pillar Salah (prayer) with other forms and practices of prayer in Hinduism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prayer_in_Hinduism) and in the Jewish religion (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_prayer);

- the pillar Zakat (obligatory charity) with the practice of dana (alms-giving) in Hinduism and Buddhism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dāna);

- the pillar Sawm (fasting) with ta’anit, a fasting practice in Judaism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ta%27anit);

- the pillar Hajj (pilgrimage) with the practice of Buddhist pilgrimage (https://www.britannica.com/topic/Buddhism/Buddhist-pilgrimage).

In so doing, you as an informative speaker not only can fascinate a Muslim audience who does not know about the similarities and differences between the five pillars of Islam and other religious and/or non-religious ethical principles, you can also fascinate a non-Muslim audience who finds the subject and information of your speech relatable, interesting, and eye-opening.

Humanize our information.

As an audience, nothing bores us to tears and/or puts us to sleep faster than listening to a string of dry facts and statistics that mean nothing or very little to us, no matter how important they are. A good informative speech is one that not only enlightens and educates us, but also keeps us engaged and entertained with its information and presentation. It is thus our job as informative speakers to make any information included in our presentation as engaging, relatable, and interesting to our audience as possible by humanizing and dramatizing it when we can.

For example, if you want to develop and present an informative speech on the internment of Japanese Americans in the U.S. during World War II (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internment_of_Japanese_Americans), instead of filling your presentation only with a laundry list of internment camp locations, number and names of Japanese American internees in each camp, and/or where in the U.S. from which each camp’s Japanese American internees were forcibly relocated, you might want to consider featuring/highlighting in your speech powerful quotes, vivid personal accounts, and/or emotional reflections from camp survivors and their children.

Similarly, you might want to also consider humanizing and dramatizing the Japanese American internment related information by comparing and contrasting it with information related to other internment camps around the world in different historical eras with which your audience has personal and emotional connections. In so doing, you have enlivened your presentation as an informative speaker and your audience will be more likely to enjoy your speech without feeling bored by, indifferent towards, and/or apathetic to the information presented.

So far, we have discussed why being clear and being interesting are both integral to a good informative speech as well as the various practices and additional guidelines we as informative speakers can follow to be clearer and be more interesting. A very helpful way to conceptualize how we may develop, research, and organize the content of our informative speeches so that they will be both clear and interesting to our audience is illustrated in the diagram below. It shows that we as informative speakers should first tap into something that is clear to our audience members (and for which they already have the frame of reference) before taking them with us on an eye-opening, thought-provoking, and horizon-expanding journey to an uncharted territory where our information is new and interesting to them (and for which they don’t already have the frame of reference). This means that not only will our audience members find our informative speech presentation both clear and interesting at the same time, their frame of reference will also be enlarged as a result of listening to our presentation.

Be Accurate.

“I was brought up to believe that the only thing worth doing was to add to the sum of accurate information in the world.”

Margaret Mead, a US-American cultural anthropologist and writer Margaret Mead – Wikipedia

While meeting both criteria of being clear and being interesting is crucial to a good informative speech, there is one more equally important criterium for a good informative speech—be accurate. No matter how clear and interesting an informative speech is, it will not be considered good unless it is accurate as well. We as informative speakers thus must treat our information and presentation with integrity and make them as accurate as possible.

Other than making sure that our informative speeches are accurately presented through the use of proper citations, accurate language, and credible supporting materials (e.g., examples, statistics, and testimonies), all of which are discussed in more detail in other chapters of this textbook, here are two additional guidelines we should pay special attention to as informative speakers:

Avoid making things up and/or spreading disinformation.

Words have real consequences. Throughout human history, especially in recent decades with the advance of internet, information technology, and social media, we have seen many examples of:

- hoax: a falsehood intentionally fabricated to masquerade as the truth (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoax),

- disinformation: false information that is spread intentionally to deceive (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disinformation),

- misinformation: false or misleading information unintentionally presented as fact (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Misinformation),

- fake news: false or misleading information presented as news (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fake_news),

- conspiracy theory: an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a sinister conspiracy by powerful groups when the are other more probable explanations (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory), and/or

- deepfake: are synthetic media in which person A’s face or body has been digitally altered so that Person A appears to be Person B instead (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deepfake).

Many of these incidents have caused serious and even deadly harms to not only individuals but also their communities. It is thus our ethical imperative as informative speakers to be truthful with the information we share in our presentations; we must not make things up and pass them on as facts, nor should we spread disinformation by sharing false information with the intention to deceive and mislead others.

Imagine that you have selected for yourself an informative speech topic on how to perform a CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) but failed to conduct any research before the presentation. During your presentation, you shared with your audience CPR steps that are completely made-up and without any validity or factual basis. Five years later, one of your audience’s loved ones encountered an emergency situation that calls for a CPR, and he/she performed the made-up CPR steps as instructed by you and caused his/her loved one’s death as a result. While you might not be legally responsible for this unfortunate death, you surely are ethically responsible for it on some level.

Check things through and avoid spreading misinformation.

Another ethical imperative for us as informative speakers is to avoid spreading false information unintentionally by checking things through and conducting sufficient research to ensure the accuracy, authenticity, and validity of the information we share in our presentations. We may do so by using a variety of sources when conducting our research so that we can get more well-rounded and less biased information that include several voices, viewpoints, and perspectives (see the chapter on research methods and skills for more details).

For example, you have seen many Wikipedia links/articles embedded throughout this chapter to help you understand and explore various subjects and concepts. To use these links/articles properly and ethically, you must know their strengths and limitations first:

Strengths

- Wikipedia provides free access to information on millions of topics to anyone with Internet capabilities.

- Wikipedia links/articles are constantly updated.

- Sources used by Wikipedia content contributors are cited; they allow further investigation into any topic.

Limitations

- Wikipedia links/articles are not considered scholarly credible and should not be cited for academic purposes since their content is written by unknown contributors (anyone can create, edit, or delete the information on Wikipedia articles).

- Wikipedia links/articles are works-in-progress with constant changes to their information.

- Wikipedia links/articles are sometimes vandalized.

Based on the aforementioned strengths and limitations, these Wikipedia links/articles should be used only as a starting point for you to conduct more in-depth research elsewhere; they are meant to be the beginning rather than the end of your exploration and research on these subjects and concepts.

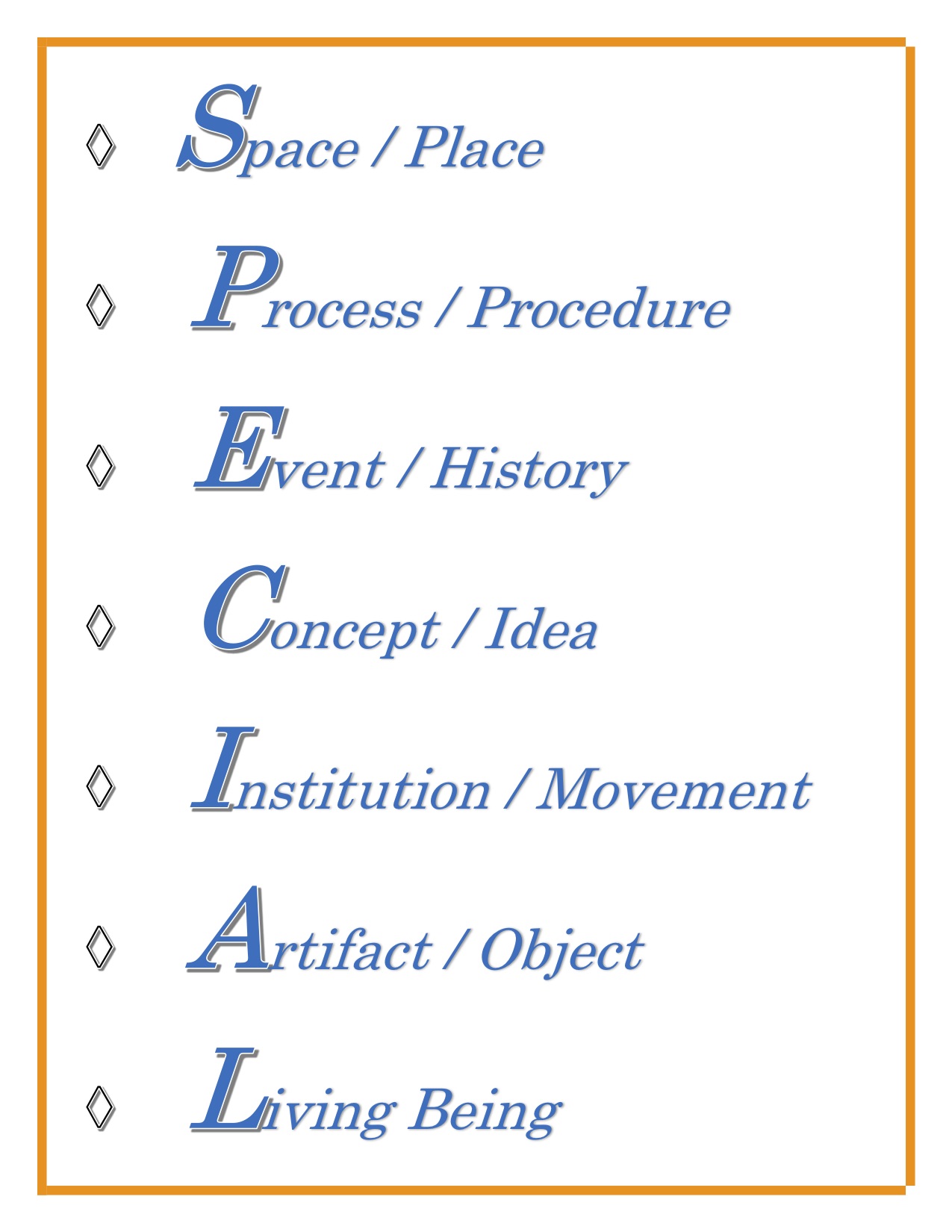

Different Categories of Informative Speeches

There are many categories of informative speeches in which we as informative speakers may develop our presentations. The seven different informative speech categories outlined below are not meant to be an exhaustive and comprehensive list; they are major informative speech categories arranged in an acronym SPECIAL to help us brainstorm, choose, and develop suitable topics for our informative speech presentations.

There are many categories of informative speeches in which we as informative speakers may develop our presentations. The seven different informative speech categories outlined below are not meant to be an exhaustive and comprehensive list; they are major informative speech categories arranged in an acronym SPECIAL to help us brainstorm, choose, and develop suitable topics for our informative speech presentations.

Space/Place

A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of a space or place, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it fictional or real, existing in the past, present, or future, located on planet earth or somewhere else in the universe, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the community roles of the barbershop and beauty salon for Black Americans in the United States (The Community Roles of the Barber Shop and Beauty Salon | National Museum of African American History and Culture (si.edu)),

- the mythical paradise called Shangri-La (Shangri-La – Wikipedia),

- the Mare Tranquillitatis or Sea of Tranquility on the Moon (Mare Tranquillitatis – Wikipedia), and

- the Korean Demilitarized Zone (Korean Demilitarized Zone – Wikipedia (United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus – Wikipedia)

are examples of an informative speech in the Space/Place category.

Process/Procedure

A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of a sequential, step-by-step, process or procedure, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it fictional or real, existing in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner. Informative speakers often present this type of informative speech as either a “how-to” speech or a demonstration speech.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- how to make the Puerto Rican dish called Mofongo (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mofongo),

- the development or distribution process for COVID-19 vaccine (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_vaccine),

- how to overcome the fear of public speaking (https://zapier.com/blog/public-speaking-tips/), and

- how to ace an interview: 5 tips from a Harvard career advisor (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHDrj0_bMQ0)

are examples of an informative speech in the Process/Procedure category.

Event/History

A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of an event or history, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it fictional or real, happening in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 (https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/),

- the Zoo Suit Riots of 1943 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoot_Suit_Riots),

- the 2021 U.S. Capitol attack (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_United_States_Capitol_attack), and

- the gender-fluid history of the Philippines (https://www.ted.com/talks/france_villarta_the_gender_fluid_history_of_the_philippines?language=en)

are examples of an informative speech in the Event/History category.

Concept/Idea

A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of an intangible and abstract concept or idea, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it an ideology, theory, philosophy, principle, doctrine, or school of thoughts, fictional or real, existing in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the critical race theory (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_race_theory),

- the trickle-down theory (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trickle-down_economics),

- the intersectionality concept (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intersectionality), and

- the principles of shamanism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shamanism)

are examples of an informative speech in the Concept/Idea category.

Institution/Movement

A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of a human-organized and human-developed institution or movement, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it fictional or real, existing in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the World Health Organization (World Health Organization – Wikipedia),

- the Chinese multinational technology company Alibaba (Alibaba Group – Wikipedia),

- the Arab Spring movement (Arab Spring – Wikipedia), and

- the African Union (African Union – Wikipedia)

are examples of an informative speech in the Institution/Movement category.

Artifact/Object

Whereas a concept/idea is something that is intangible and abstract, an artifact or object is something that is tangible and concrete. A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of an artifact/object, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it fictional or real, existing in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the Tibetan prayer wheel (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prayer_wheel),

- the headwrap called do-rag or durag (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Do-rag),

- the musical instrument didgeridoo (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Didgeridoo), and

- the traditional African masks(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traditional_African_masks)

are examples of an informative speech in the Artifact/Object category.

Living Being

Whereas an artifact/object is something that is inanimate, a Living Being is something/someone that possesses the characteristics of being alive. A presentation focusing on certain specific aspects of a Living Being, especially a lesser-known one or lesser-known information about a well-known one, be it a plant, animal (including a person or a group of people), insect, fungus/yeast, bacterium, or amoeba, fictional or real, living in the past, present, or future, is suitable for an informative speech as long as it is presented in a neutral manner.

For instance, a neutral presentation on the various aspects of:

- the Uyghur ethnic group (Uyghurs – Wikipedia),

- the U.S. American writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin (James Baldwin – Wikipedia),

- how fungi recognize (and infect) plants (How fungi recognize (and infect) plants | Mennat El Ghalid – YouTube), and

- the Amazon Rainforest (Amazon rainforest – Wikipedia)

are examples of an informative speech in the Living Being category.

Special Consideration to Be Given in the Informative Speech-Making Process

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

–Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a Nigerian writer who was awarded the MacArthur Genius Grant in 2008 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimamanda_Ngozi_Adichie

As the saying goes, history is written by the victors. This means that those who are in positions of power and dominance, be they based on race, ethnicity, national origin, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or any of the other major identity markers, have the ability to dictate, censor, control, distort, and/or erase histories as they see fit to maintain and perpetuate their own wealth, power, privilege, and dominance.

This also means that in order for our community/society/world to change its course for the better and become a more equitable, inclusive, and just one, histories of those who have long been marginalized must be actively uncovered/recovered, publicly acknowledged, widely made visible, and systematically preserved. Our textbook’s earlier chapter entitled “Questioning and Decentering the History of Public Speaking” is written with this same goal in mind—to challenge the mainstream, Eurocentric, narrative about public speaking and to shed light on other lesser-known histories about, and cultural perspective on, public speaking.

Similarly, when it comes to information, those who are in positions of power and dominance tend to use it, intentionally or unintentionally, to maintain and perpetuate their own wealth, power, privilege, and dominance; not only do they have much greater access to receive and share information, the information they receive and share is also considered by most to be of much greater value and influence. Therefore, while we as informative speakers may freely choose any topics in the aforementioned major categories (i.e., SPECIAL: Space/Place, Process/Procedure, Event/History, Concept/idea, Institution/Movement, Artifact/Object, and Living Being) on which to develop our presentations, to help our community/society/world evolve into a more equitable, inclusive, and just one, I encourage everyone to disrupt and enrich dominant, mainstream public discourse by choosing topics related to communities, be they based on race, ethnicity, national origin, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or any of the other major identity markers, that have been historically marginalized, underrepresented, and/or underserved.

In so doing, we may avoid the danger of a single story discussed in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s aforementioned inspiring quote on page 19 and in her celebrated TED talks here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg) and collectively make lesser-known histories, experiences, perspectives, and voices more visible, acknowledged, and valued.

Summary

We have discussed in this chapter why neutrality is key to informative speaking/speeches, how being clear, interesting, and accurate all at once (i.e., the CIA’s of a good informative speech) makes any informative speeches good, and the major categories (i.e., the acronym SPECIAL) on which we can develop our presentations as an informative speaker. It’s now time for us to apply the knowledge, strategies, guidelines, and special considerations that we’ve learned from this chapter to practice as we develop and present our informative speech presentations.

Remember Ms. Sanchez’s inspiring quote in the beginning of the chapter “I cannot tell the truth about anything unless I confess being a student, growing and learning something new every day. The more I learn, the clearer my view of the world becomes”? Your informative speech presentations for this course are not merely assignments/exercises for points/grades; rather, they are powerful vehicles to help your audience grow/evolve and see the world more clearly. Take full advantage of them and make our community/society/world a better place with your informative speech presentations!

Class Activities

Watch the following youtube clips:

- The Danger of a Single Story

- How Fungi Recognize (and Infect) Plants

- The Gender-Fluid History of the Philippines

- How to Ace an Interview: 5 Tips from a Harvard Career Advisor

After reviewing these clips, reflect on the following questions:

- Are these presentations considered more informative or persuasive (e.g., are they neutral in their content and presentation)? If so why and if not why not?

- If these presentations are more informative than persuasive, do you consider them good informative speeches (e.g., are they clear, interesting, and accurate all at once)? If so why and if not why not?

- If these presentations are more informative than persuasive, which major informative speech category or categories (i.e., SPECIAL: Space/Place, Process/Procedure, Event/History, Concept/Idea, Institution/Movement, Artifact/Object, and Living Being) do they each fall under?

- If these presentations are more informative than persuasive, do you think they help disrupt and enrich dominant, mainstream public discourse by sharing information related to communities, be they based on race, ethnicity, national origin, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or any of the other major identity markers, that have been historically marginalized, underrepresented, and/or underserved? If so why and if not why not?

For more information about the author of this Chapter, please visit Professor Vincent (Tzu-Wen) Cheng’s faculty page here .

Works Cited

Lucas, Steven. “Speaking to Inform.” The Art of Public Speaking, 13th. ed., McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY, 2019, pp. 268–289.

“Public Speaking & Speech Resources: The ‘6 W’s’ Method.” Windward Community College Library, 4 Jan. 2022, https://library.wcc.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=35279&p=3073195.

“Reciprocity Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/reciprocity.

“Jargon Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jargon.

“Wikipedia: Strengths and Weaknesses.” LibGuides, https://pitt.libguides.com/wikipedia/prosandcons.

HarvardExtension. “How to Ace an Interview: 5 Tips from a Harvard Career Advisor.” YouTube, 27 Mar. 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHDrj0_bMQ0.

Villarta, France. “The Gender-Fluid History of the Philippines.” TED, https://www.ted.com/talks/france_villarta_the_gender_fluid_history_of_the_philippines?language=en.

TEDtalksDirector. “How Fungi Recognize (and Infect) Plants | Mennat El Ghalid.” YouTube, 19 Apr. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qpfq3xCdAu4.

TEDtalksDirector. “The Danger of a Single Story | Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.” YouTube, 7 Oct. 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg.