1 Questioning and Decentering the History of Public Speaking

Scott Tulloch, Ph.D.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- Describe the historical narratives (i.e., stories about the past) typically presented in public speaking textbooks.

- Explain the social and political power of historical narratives.

- Discuss alternative histories of public speaking.

- Reflect on the diversity of public speaking practices today in relation to your particular cultural identities and speech communities.

Introduction

Winston Smith, the protagonist in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, works for the Ministry of Truth. Winston’s job is to revise old newspaper articles to present a version of history consistent with the totalitarian government’s current propaganda. Stories and documents that do not fit into the government’s ideal design of the past are tossed aside into tubes known as memory holes, in route to be destroyed in burning furnaces beneath the Ministry of Truth. Winston is continually reminded of the ruling Party slogan, “Who controls the past [ . . . ] controls the future : who controls the present controls the past” (Orwell 33). The slogan implies many important insights about history, the stories that societies tell about the past. History is not a neutral or objective record of the past, but rather a social construct constantly revised to serve present purposes. The telling of history is not full or complete. Stories about the past highlight and erase, include and exclude. Most importantly, history exists within systems of power and can be told in ways to preserve the status of those in power.

I want you, in this chapter, first to critically examine the version of history typically presented in public speaking textbooks and then to consider and reflect on the much wider and richer history of this practice across the globe.

The Typical Historical Narrative of Public Speaking

Public speaking textbooks often retell a very selective history, which focuses on a European tradition of public speaking, namely Greek and Roman contributions. Inevitably there are depictions, like the one below, of white men in togas, deep in thought and discussion.

In textbooks, figures such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian are celebrated frequently, while only a few sentences acknowledge public speaking in other cultural groups’ histories. For example, in a chapter on the origins of public speaking in Public Speaking, Peter DeCaro acknowledges that “the art of public speaking was in practice well before the Greeks,” but he chiefly credits them with systematizing the art of public speaking. From DeCaro’s perspective, the art of public speaking has undergone a number of changes in various historical periods and with new technologies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. However, according to DeCaro, “What we know today as the art of public speaking [ . . . ] since the days of the Greeks and Romans, St. Augustine, and Descartes [ . . . ] hasn’t changed; it has basically remained the same” (1). In DeCaro’s estimation this European tradition is the be all and end all, incapable of improvement even thousands of years later.

Stephan Lucas, in The Art of Public Speaking, notes in passing that public speaking has been “studied around the globe for thousands of years,” but continues to report:

In classical Greece and Rome, public speaking played a central role in education and civic life. It was also studied extensively. Aristotle’s Rhetoric, composed during the third century [367–322] B.C., is still considered the most important work on its subject, and many of its principles are followed by speakers (and writers) today [ . . .] Over the centuries, many other notable thinkers have dealt with issues of rhetoric, speech, and language—including the Roman educator Quintilian, the Christian preacher St. Augustine, the medieval writer Christine de Pizan, the British philosopher Francis Bacon, and the American critic Kenneth Burke. (Lucas 5)

Lucas concludes this historical summary stating, “Your immediate objective is to apply those [European] methods and strategies in your classroom speeches” (Lucas 5). Europeans are presented as the primary sources of knowledge about the art of public speaking in most textbooks. Put bluntly, many public speaking textbooks are Eurocentric, presenting a narrow worldview that focuses on European culture and history, while excluding cultures and histories in other regions of the world.

Problems with the Eurocentric Narrative

It is often pointed out, justifying the Eurocentric focus, that Greeks and Romans receive so much attention because they developed a special area for the study of public speaking, called rhetoric. In other cultural traditions, however, instruction on public speaking was spread out among lessons on other subjects, such as politics, ethics, poetry and composition. Regardless, fixation on a European tradition of public speaking is problematic for a variety of reasons.

Privileging a Eurocentric history may lead to false conclusions that the art of public speaking is an invention unique to the West, as if it never would have existed without the “enlightened” and “high-culture” of Europe. This assumption is patently false. Even worse, denial of non-Western cultures’ public speaking traditions implies their contributions are less important or sophisticated, fueling some of the worst forms of cultural prejudice and bigotry.

Furthermore, standards of public speaking developed by Greeks and Romans are not universals. European approaches to public speaking are expressions of Western culture, most applicable within the context of other Western cultures. In other words, what worked in ancient Greece may not necessarily work as well in other places or times. Eurocentric approaches to public speaking, neglecting the ways in which non-Western cultures understand and practice public speaking, limits a speaker’s ability to communicate competently to global audiences.

Stories about the past construct a social reality in the present. The Eurocentric history influences public speaking practices and norms of communication today. Embedded in the European history of public speaking are lessons about what types and styles of speech are valued. An image of “good” speech and a “competent speaker” are implied, establishing a standard for judging speech. If a Eurocentric perspective defines what is “good” public speaking, speakers who don’t speak “well” within those Eurocentric constructs may be marginalized and disempowered in public speech. In the worst case, public speaking textbooks present an ethnocentric (i.e. evaluating other people and cultures according to the standards of one’s own culture) framework for evaluating speech.

Finally, consider the consequences when a textbook or teacher with authority describes the past, and your ancestors and communities are not included. This lack of representation erases those voices in the past, while disempowering them in the present. For example, research since the 1970s has continually found an education achievement gap between minority and white students (“Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gaps”). While many factors contribute to this achievement gap (racism, unequal funding, biased standardized testing, etc.), a lack of cultural representation in educational materials certainly contributes to the problem. In fact, recent studies suggest that culturally inclusive education programs, focusing on minority students’ cultures and identities, leads to significant improvement in academic performance (attendance, GPA, graduation rates, etc.) among those students. The critical thinking skills and self-esteem developed from being represented and included benefits students’ education (Anderson 2016).

I believe that recognizing the diversity of public speaking practices in the past is a crucial first step in valuing the diversity of public speaking practices and creating a more inclusive and equitable public today. I will, in the rest of this chapter, direct attention to multiple alternative histories of public speaking. An essential part of becoming a better speaker involves recognizing yourself, and speakers you identify with, in the history (and hence the future) of public speaking.

Note that the history that follows, like all others, is selective and incomplete. I have only so much space, and choices must be made. To learn more about the politically biased histories in textbooks, check out the interactive article “Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories” from The New York Times.

Public Speaking Before and Beyond the Greeks

There are multiple histories of public speaking, beginning at different times and places around the globe. In fact, there is absolutely no doubt that attention to public speaking predates the Greeks by thousands of years.

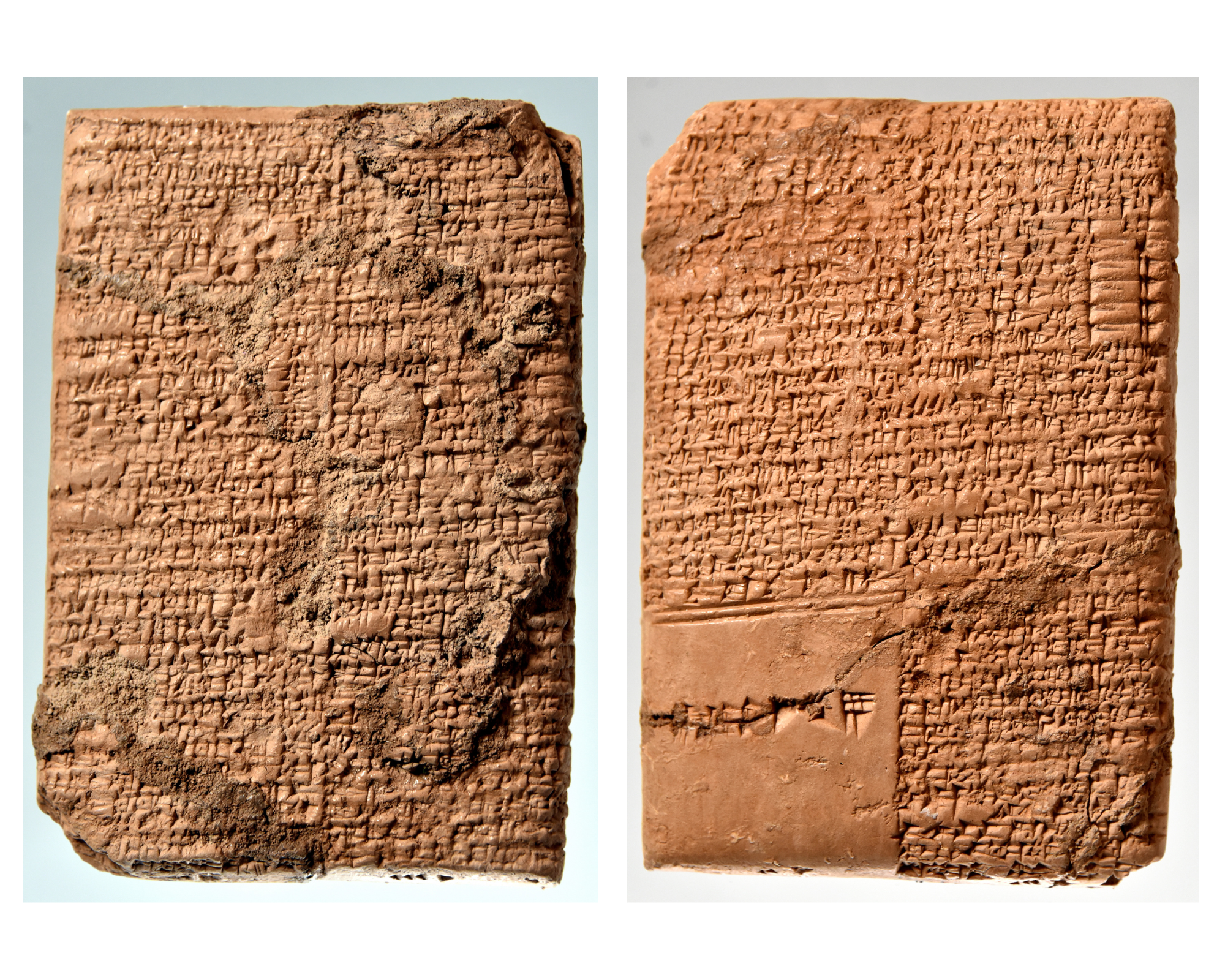

The Fertile Crescent

Opportunities for public speaking go as far back as when civilizations, such as the Sumerian and Akkadian Empires in Mesopotamia, first began to develop. These earliest civilizations were located on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the area of present day Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Kuwait.

In these first civilizations, a council of elders, made up of older, experienced, and wealthier members of society, would debate issues impacting their city. Council members would speak, trying to build consensus among the council. In the end, however, an assembly of adult males of the city would make and confirm final decisions. These first forms of public speaking and participatory policy-making are described in the epic poem Gilgamesh and Aga (1900–1600 BCE).

The poem describes a conflict between the rulers, named Gilgamesh and Aga, of two cities. Aga sends a message to Gilgamesh threatening war and ordering him to give over the city and his people to become slaves. Gilgamesh gathers and speaks to the council of elders who decide they should submit and allow Aga to take over the city. Gilgamesh disagrees with the council’s decision and summons the full assembly of men in the city, speaking directly to them and making an appeal to defend the city. The assembly agrees they should fight Aga. When Aga’s army attacks the city, ultimately he is captured and concedes to Gilgamesh. The story of Gilgamesh and Aga served to model ideal forms of public speaking and decision-making processes in Mesopotamian societies.

Ancient Africa

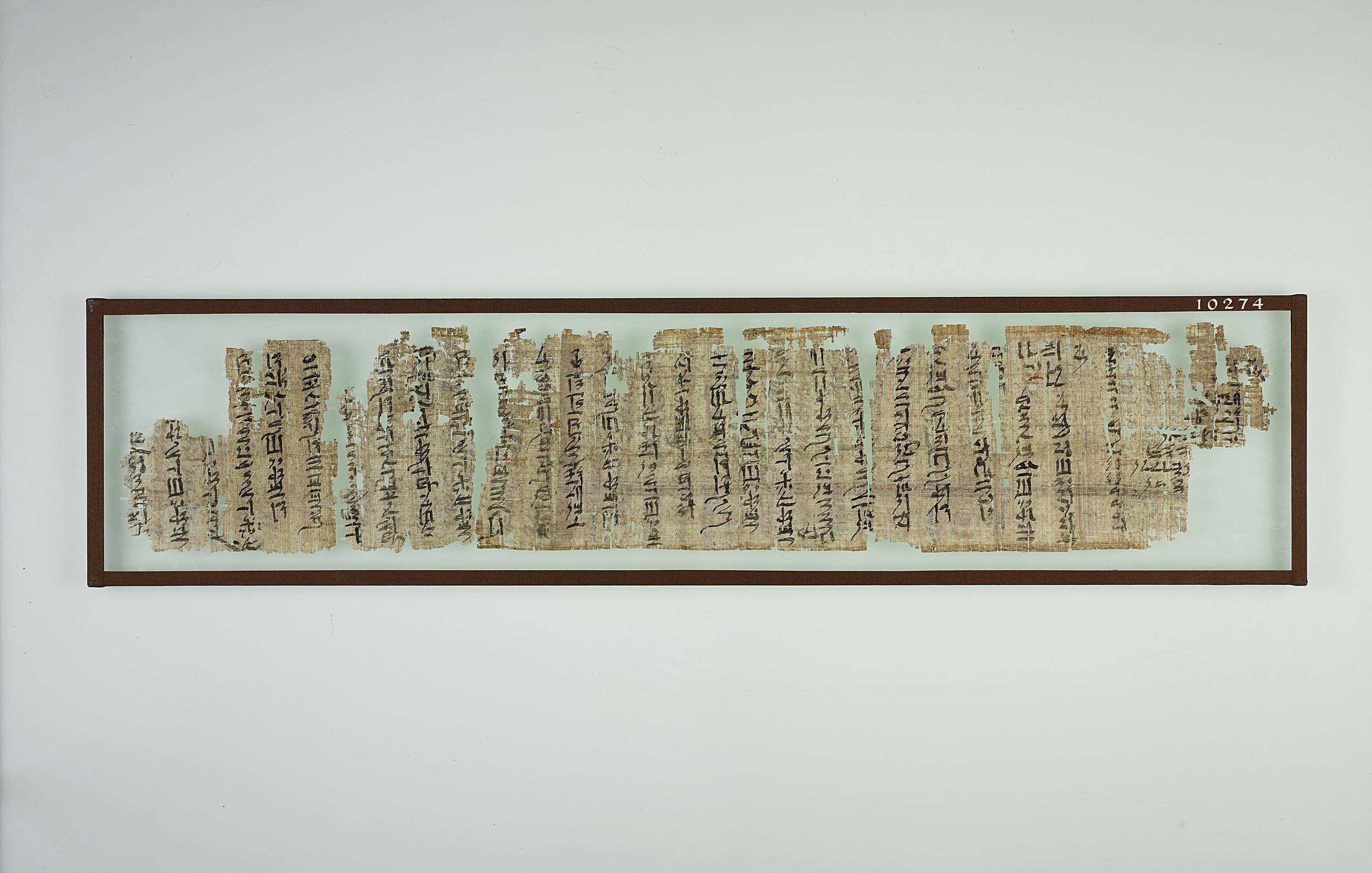

Public speaking traditions can also be found in ancient African societies. There is much evidence that ancient Egyptians valued eloquence and realized the power of speech. One document revealing the importance of speech in ancient Egyptian society is the “Story of the Eloquent Peasant,” which was a rhythmic poem composed between 2000–1800 BCE.

The author of the story is anonymous, which is common during this period. No complete version of the story has survived, however, the overall arch of the tale has been reconstructed from fragments of four incomplete scrolls. The story involves a peasant named Khun-Anup, whose goods and donkey are stolen on the way to market by a greedy landowner and vassal to the Pharaoh, named Nemtynakht. The peasant tries to recover his goods and appeals to Rensi, a local magistrate and high official, by delivering a powerful persuasive speech. Rensi is so impressed by the peasant’s eloquent speech that he transcribes it and sends a written copy to the Pharaoh. The Pharaoh is also impressed by the speech and orders the peasant to keep pleading his case so more speeches can be recorded. The peasant is exhausted and, after nine days of speaking, refuses to speak more. Rensi is so inspired by the final speech he orders all of Nemtynakht’s property be given to the peasant as a reward for his eloquence. The story reveals much about ancient Egyptian ethics and justice, but also how prized eloquent speech was in that culture.

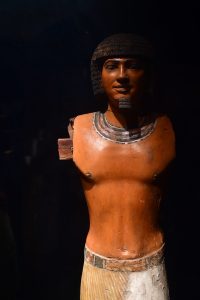

The most important document of public speaking in ancient Egypt is a handbook called the Instruction of Ptahhotep (2375–2350 BCE). The Instruction of Ptahhotep is considered to be one of the earliest surviving books, as well as the oldest known rhetorical handbook. The author, Vizier Ptahhotep, served as an important minister during the reign of Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi.

Ptahhotep, who lived to be very old, was getting ready for his son to take over his work. The handbook was intended to provide instruction to his son and other future ministers. Advice on speech is given throughout the book. In one maxim from the handbook Ptahhotep states, “No artist’s skills are perfect; Good speech is more hidden than greenstone. Yet may be found among the maids at the grindstones” (qtd. in Kennedy 129). In other words, naturally talented speakers are uncommon, but speaking is a skill that can be sharpened with study and practice. The handbook also provides advice for communicating with people across the Egyptian social hierarchy, including: those more powerful, those that are equal, and those who are not equal. For example, when meeting a person more powerful, the reader is instructed to “Fold your arms, bend your back, To flout him will not make him agree with you [ . . . ] Your self control will match his pile (of words)” (qtd. in Kennedy 129). There are some important differences between Egyptian and Greek rhetoric. Egyptians focused less on analyzing examples of speech to identify argument, organization, or stylistic devices and instead taught an attitude that would make one’s speech effective while maintaining harmony in the social order (Fox 21–22).

Even in other ancient African cultures that hadn’t developed written language yet, there is evidence of public speaking traditions. Kermit Campbell studied early African rhetorical traditions in Nubia (present-day Sudan), Axum (present-day Ethiopia, Sudan, and Yemen), and the Mali Empire (spanning a range of present-day West African countries). According to Campbell, “Africa has quite varied and complex uses of oral and written language, and any general theory or concept of rhetoric must take these into account” (258–259). Ancient societies across Africa had a great diversity of public speaking traditions and practices.

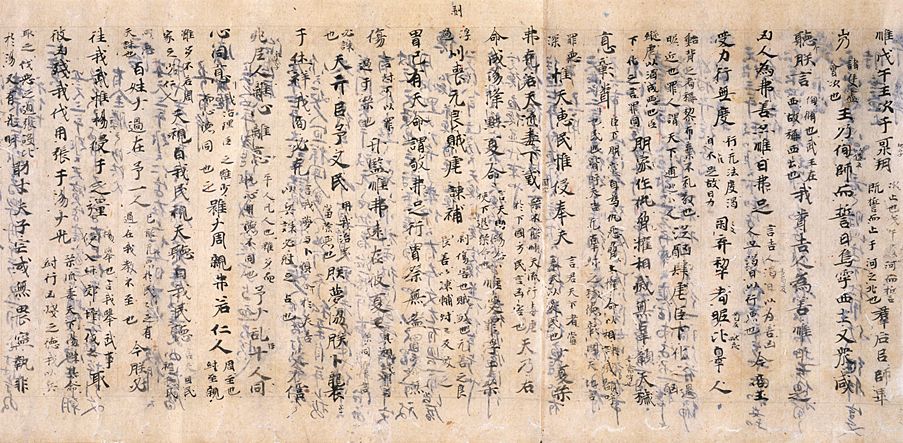

China

China, which has written language dating back to the second millennium (2000–1000 BCE), has an extensive public speaking tradition. The Chinese had a variety of terms to conceptualize different aspects of public speaking, including: yan (language, speech,), ci (artistic expression), shui (face-to-face persuasion), and bian (disputation and argumentation), which is considered most central to ancient Chinese theories of speech and persuasion (Lu 4). Speech did not have its own division in the traditional Chinese arts; instead lessons about speech were scattered across a variety of subjects. According to Robert Oliver, in Greece public speaking was so important it had to be explored and considered as a special field of knowledge. In Asian cultures, rhetoric was so important that it was considered united and in harmony with other fields of knowledge, such as ethics, politics, philosophy, and the arts (Oliver 10). Effective speech was prized in ancient China and texts of exemplar speeches were preserved to serve as instructional models for invention and style. Examples of effective speech were often addressed to an individual ruler or a small group of political advisors. Chinese rhetoric was not concerned with speech addressed to the general public or techniques to address a mass audience.

There are hundreds of formal speeches attributed to rulers, officials, and philosophers, which provide a body of rhetorical texts unmatched even in Greece and Rome (Campbell 142). These model speeches can be found in a variety of sources, but one of the most extensive collections is in Shu Ching, also known as the Book of History.

Shu Ching is a collection of writings, by anonymous authors, about events involving kings who reigned from 2200 to 628 BCE. The book became an important part of education for civil service. Over fifty speeches by emperors, generals, and other high officials are included in Shu Ching. Speeches in Shu Ching tend to fall into three categories: deliberative speech aimed at persuading an individual or audience of high officials; announcements by a ruler or high official that describe a public policy or response to a political problem; or instructions from a high official to a ruler where the speaker is honest and avoids flattery. Robert Oliver summarizes key insight from the Shu Ching, stating that “to rule well meant to communicate honestly, intelligently, and effectively…Ministers must be courageous in speaking with utmost frankness to their monarchs [ . . . ] Social harmony and individual dignity…could not be attained by evasive speaking, by false flattery, or by curbing honest criticism” (102–120). Important aspects of the Chinese rhetorical tradition are also found across the work of various Chinese philosophers, including Confucius, Mencius, Mo Tze, and Lao-Tzu. In the Analects, the most important sources of Confucius’ teachings, speech is considered at several points. For example, Confucius is reported to have said “One who has accumulated moral power will certainly also possess eloquence; but he who has eloquence does not necessarily possess moral power” (qtd. in Kennedy 153). Like other ancient cultures, Chinese standards for effective speech emphasized consensus-building, social harmony, and respect for authority. However, the degree in which the Chinese tradition emphasized frankness and sincerity in political contexts is not found in other ancient societies.

India

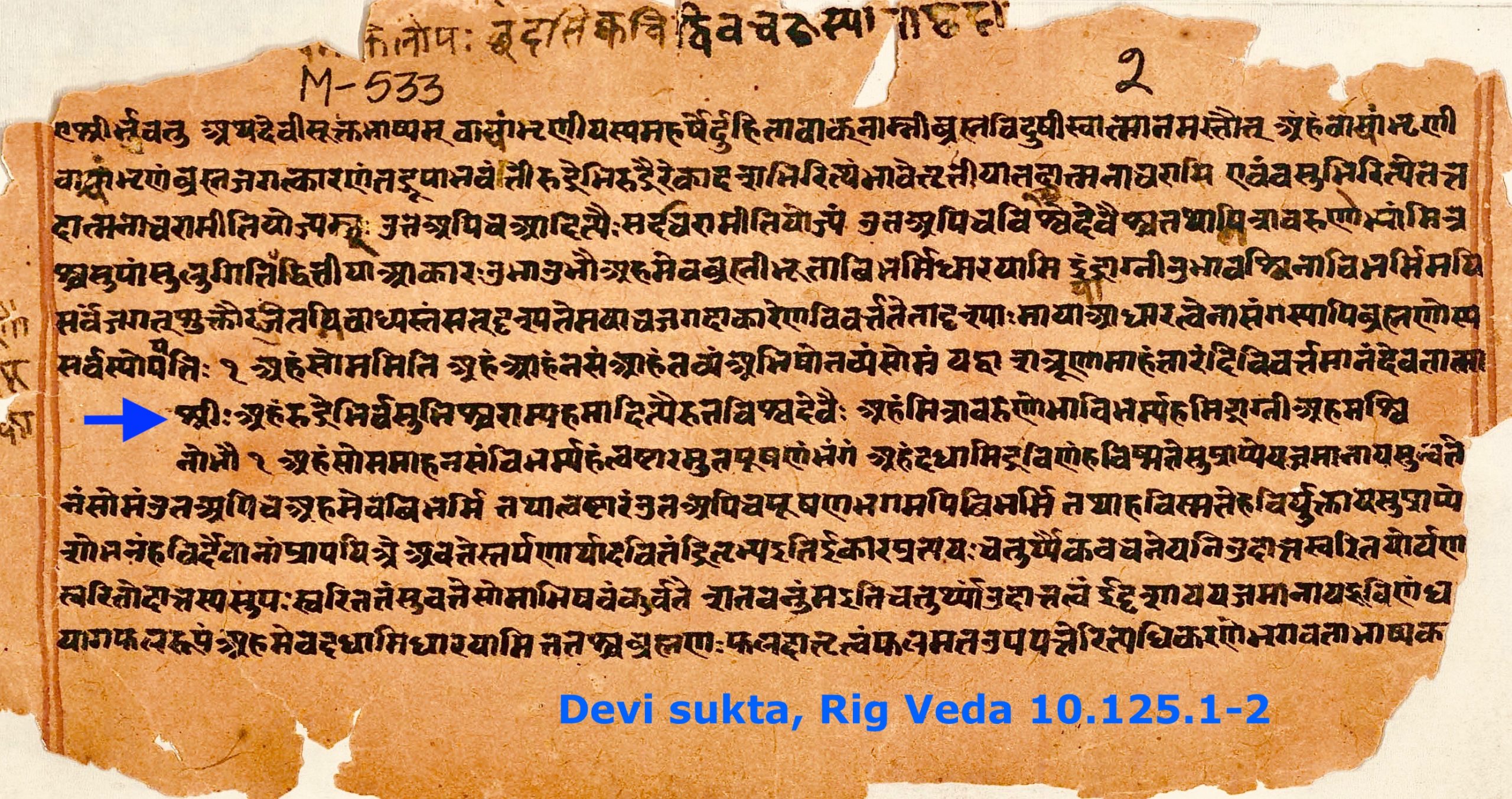

India also had a rich public speaking tradition, although documentation is scarcer than the records in ancient Africa and China. Indians, despite having developed a system of written communication, placed a higher value on speech, and it served as the primary form of communication for literary and scientific activity (Campbell 172; Oliver 22). Unlike in Egypt and China, historical records and literature were transmitted through the spoken word, memorized and recited to pass down among generations. Written records that have survived were recorded centuries after being spoken. Ancient Indians did speak in public settings, among an audience, but speech was often limited to those higher in the social hierarchy, members of the highest Brahmin caste and religious priests (Hindu, Buddhist, etc.). While public assemblies were elite, there is evidence of early forms of participatory politics in ancient India. Attention to public speaking in ancient India is present in a collection of hymns, the Rig-Veda (1500–1000) BCE, which originated from the region of present day Pakistan.

Some of the hymns describe the Sabha, an assembly of elders, and elected councils where public speaking, debate, and free discussion would occur about local affairs. The councils seemed to have a role in naming kings, but also maintained independence from their rulers. The goal of debate was not to win a majority vote, but rather to arrive at consensus and create unity among the council. The final hymn of Rig-Veda encapsulates the ideal function of the council to achieve consensus, “Assemble, speak together; let your minds be all of one accord . . . The place is common, the assembly, common the mind, so be their minds united . . . One and the same be your resolve, and be your minds of one accord; United be the minds of all that may happily agree” (qtd. in Oliver 26). Speech was not to be directed by individual interests or described in personal terms. The effectiveness of a speaker lied in the ability to express common beliefs, values, and interests of the entire community.

The role of debate in ancient India, especially among the Brahmin caste, is highlighted in a collection of Hindu philosophical texts known as the Upanishads. The Upanishads are a series of collected sermons and dialogues. The Upanishads serve as instructions for how members of the elite Brahmin caste should conduct themselves in speech and debate. A devotion to truth and resistance to persuasive speech driven by personal preferences is clear. One Brahmin is scolded in a dialogue for a self-absorbed speech where they showed off their superior knowledge. “Let a Brahmin renounce learning and become a child . . . Let him not seek after many words, for that is mere weariness of the tongue” (qtd. in Oliver 28). A clear characteristic of ancient Indian rhetoric is the emphasis on consensus and ability to speak on behalf of community values and interests. This stands in stark contrast to the majority vote system and emphasis on individualism that influenced public speaking practices in ancient European cultures. Later in ancient India, by the third century (300–400 CE), attention to literary composition became common. Indians closely studied lyric poetry and developed a “science of figures,” or alamkara-shastr, dividing style into several types and qualities, such as clarity, vigor, and compactness.

The Americas

North American Indians also had a vibrant public speaking tradition. To make any generalization about Native American public speaking practices is challenging, as the population consisted of several hundred distinct groups, speaking many different languages, and living a variety of lifestyles ranging from hunter-gatherer, agriculturalists, to tighter knit communities comparable to urban societies. Public speaking norms and practices passed down through generations orally, so written documentation of ancient public speaking practices is scarce. Most documentation comes in the form of reports from European conquerors, colonists, missionaries, and traders. These documents are problematic because they are written from the perspective of the white colonizer. For example, one of the earliest descriptions of Native American oratory is documented in The Florida, which provides a favorable description of Hernando De Soto’s brutal exploration of the present-day southeastern United States.

The author describes the speeches they encountered and remarks, Native American chiefs “appeared to have been influenced by the most famous officers of Rome [ . . . ] and that the youths appeared to have been trained in Athens” (qtd. in Campbell 84). Another portion of documentation of Native American rhetorical traditions comes in the form of records of Indian responses to white settlers at treaties and conferences, which were published in newspapers. Despite the limited and often biased records that exist, Native American societies tended to be more egalitarian in public speaking. It was common for both men and women to be able to speak in assemblies. The goal of deliberation was to produce communal consensus. While there isn’t much evidence of judicial speech, Native Americans developed rich epideictic, or ceremonial speech practices for funerals, war, and other ritual occasions.

The Aztecs developed a rich public speaking tradition, with a pictograph writing system and formal education that included specific training in public speaking, much like schools in Greece. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Fransican Friar who arrived in Mexico in 1529, studied and wrote an encyclopedia on Aztec society that included transcriptions of over eighty speeches known as huehuetlatolli, or “speeches of elders.”

These speeches were used as models of ideal speech and were studied in schools for priest and warrior classes. Sahagún says that boys were thoroughly instructed in speech [and] he who did not speak well, who did not greet people properly, they pricked [with thorns]. According to Sahagún, in Aztec culture “wise, superior, and effective rhetoricians were held in high regard. And they elected these to be high priests, lords, leaders, and captains, no matter how humble their estate” (qtd. in Campbell 101). Emphasis on speech in Aztec education shares similarities with the other cultural traditions described in this chapter.

The Legacy of Colonization

Colonization is one of the main reasons a European tradition of public speaking gains such prominence around the globe. Colonization relied upon not only forms of physical violence, but also intellectual violence. Untold numbers of oral traditions and non-Western public speaking practices have been lost to history, viciously displaced by the traditions of colonizers. As Europeans colonized the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Americas, they carried their texts and intellectual traditions. However, it’s not as if the colonized took the European tradition and approach to public speaking as is. Instead the European tradition was revised to fit within their culture and public speaking traditions. For example, medieval Muslim scholars studied the Greek rhetorical tradition and Aristotle, imagining an “Arabic Aristotle,” and adapting it to fit within Islamic culture. Muslim scholars, in their own commentary on rhetoric and oratory, transmitted Arabic concepts of oratory and rhetoric back to Europe (Borrowman 342).

There are multiple rhetorical traditions and histories of public speaking. This expanded history reveals what appears to be universal interest and attention to public speaking, not something singular or unique to European cultures. Almost all cultures have a word to describe someone skilled at public speaking, such as orator. Many cultures have terms designating particular types of speaking situations. Many cultures also have terms for stylistic devices in speech, such as metaphors and proverbs. Handbooks and guidelines for “good” speaking were present in several cultures, particularly in early literate cultures, such as ancient Egypt, China, and the Aztecs. Otherwise, in societies without written language, norms and ideal practices of public speaking were taught by elders and passed down orally. A range of public speaking practices and traditions existed (and persist) across many cultures.

Conclusion

Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican political activist who built a Pan-African movement inspiring solidarity between all ethnic groups of African descent, famously declared that a people “without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots” (qtd. in Dadzie 11). My goal in this chapter was to critique the Eurocentric history that dominates public speaking textbooks. I attempted to provide a more inclusive history of public speaking. I hope at this point you can find a space in the past for yourself, and your ancestors, within this expanded history of public speaking.

I also hope that you see a space for your own unique public voice in the present. I want to urge you, in closing, to take some time to reflect on your own cultural identities and how they influence your communication style and approach to public speaking. As you practice the art of public speaking do not deny or silence those aspects of your identity. Be proud of the cultural traditions that make your voice ring unique. No matter your identity or communities, there is a place for your voice in the past, present, and future of public speaking.

Review Questions

- Consider the statement, “History is never neutral or objective.” What does this mean? Do you agree or disagree? Why or why not? Can you think of examples that support or contradict this statement? What does this have to do with public speaking?

- What are the implications and consequences of emphasizing European history and norms of public speaking norms at schools and in textbooks?

Class Activities

- Have students consider and write a response to the question below. After they have drafted their responses, pair or group students to share and discuss their responses. Next, bring the class together for a group discussion about the range of qualities that are part of being a “good” speaker and the diversity of public speaking practices.

- Who is someone from your community or that you share similarities with, in terms of your cultural identity or background, you consider to be a “good” public speaker? What characteristics and qualities make that person a “good” speaker? You may also explain why you connect and identify with that speaker.

- Note that responses do not need to be tied to “traditional” public speakers or political speech. There are many different types of public speakers—comedians, entertainers, religious leaders, various types of professionals, etc. Also, don’t forget the public speakers you’ve had contact with in your own daily lives and experiences.

- Have students complete the social identity wheel worksheet. Ask students to consider how aspects of their cultural identities and affiliation with various speech communities influence their communication style and public speaking.

Works Cited

Anderson, Melinda D. “The Ongoing Battle Over Ethnic Studies.” The Atlantic, 7 Mar. 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/03/the-ongoing-battle-over-ethnic-studies/472422/. Accessed 13 July 2021.

Borrowman, S. “The Islamization of Rhetoric: Ibn Rushd and the Reintroduction of Aristotle into Medieval Europe.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 2008, pp. 341–360.

Campbell, Kermit E. “Rhetoric from the Ruins of African Antiquity.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, vol. 24, no. 3, 2006, pp. 255–274.

Dadzie, Stella. A Kick in the Belly: Women, Slavery & Resistance. Verso, 2020.

DeCaro, Peter. “The Origins of Public Speaking.” Public Speaking: The Virtual Text. The Public Speaking Project, 2011. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Communication/Public_Speaking/Public_Speaking_(The_Public_Speaking_Project)/02:_Origins_of_Public_Speaking

Fox, Michael V. “Ancient Egyptian Rhetoric.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, vol. 1, no. 1, 1983, pp. 9–22.

Kennedy, George A. Comparative Rhetoric: An Historical and Cross-Cultural Introduction. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Lu, Xing. Rhetoric in Ancient China Fifth to Third Century B.C.E.: A Comparison with Classical Greek Rhetoric. University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

Lucas, Stephen E. The Art of Public Speaking. 11th ed., McGraw Hill, 2012.

Oliver, Robert T. Communication and Culture in Ancient India and China. Syracuse University Press, 1971.

Orwell, George. 1984. Harcourt, 1949.

“Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gaps.” Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://cepa.stanford.edu/educational-opportunity-monitoring-project/achievement-gaps/race/. Accessed 13 July 2021.

characterizing a worldview that focuses on European culture, history, and values

the art of speaking and writing effectively; the study of this art