9 World War II

Chapter Outline:

As mentioned, at the end of World War I the people took a 20 year time-out and went right back to it with World War II. We know what happened in those 20 years, let’s look at what set things off and how this train reached its final destination…

- The Road To War in Europe

- The Road To War in East Asia

- 1940-1942: Axis Conquests in Europe and Asia

- Allied Victories

- The Conclusion

- The Holocaust

- Pacific War

- US Industry and The “Home Front”

However, World War II was also a result of the worldwide reaction to the Great Depression, which was seen by many as not only a failure of capitalism, but also a failure of democracy. Fascism and communism seemed to some to offer the only plausible reactions to the crisis. Germany was not alone in abandoning democracy and embracing authoritarianism; the same happened all over Eastern and Central Europe, Latin America, and, most importantly, Japan. The last chapter presented how the Japanese military, taking the initiative against the weak objections of Japan’s elected government, initiated the conflict that would become World War II by invading and occupying the northern Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. Again, it is striking how similar the racial beliefs in the Japanese military were to those of the Nazis: the “Yamato” people of Japan had a special mission to dominate East Asia in the same way that the “Aryans” of Germany were destined to rule all of Europe.

The Road to War in Europe

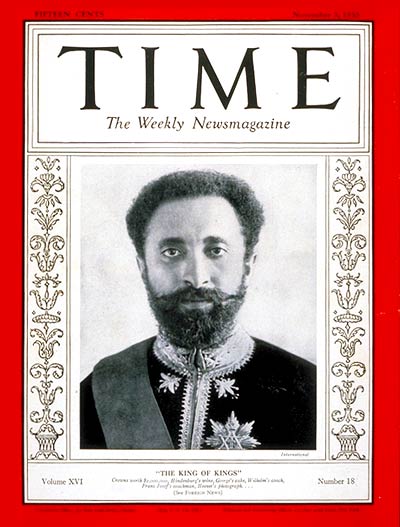

The belief that their nation’s greatness lay in war and conquest was fundamental to fascist ideology in both Italy and Germany. While Hitler was still consolidating the Nazi regime and rebuilding German armed forces in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Mussolini decided to act. In October 1935 Italy invaded independent Ethiopia from its colonies in Eritrea and Somalia. The Italians had been defeated by the Ethiopians in 1896; this time was different. Using air power and poison gas, Mussolini’s military swept through Ethiopia. By the end of 1936, most pockets of Ethiopian resistance were defeated. In April 1936, Ethiopian King Haile Selassie went to the League of Nations to ask for help, but the League had no army to attack Mussolini’s.

Emboldened by the ineffectiveness of world opinion, the Italian occupation of Ethiopia was brutal. In February 1937, in response to an attempted assassination on the new Italian viceroy in the capital city, Addis Ababa, Italians went on a three-day killing spree to exact vengeance on the Ethiopians. At least 20,000 were murdered, including Ethiopian intellectuals who had already been imprisoned in wretched conditions. As we’ll see, such atrocities were typical of the racism inherent in fascist regimes, who thought that using such terror was the only way to “teach a lesson” to “inferior” conquered peoples.

After losing most of its Latin American colonies in the early nineteenth century, Spain fell into decades of civil wars. In the early years of the new century, Spanish workers were inspired by socialism and anarchism, the belief that taking down all forms of repression would liberate the natural socialist and communal tendencies of humanity. Many found fault with the Catholic Church, which received government funds to educate and provide welfare for the poor, but was seen as ineffective and hypocritically enjoying its own riches by the starving, illiterate, and landless peasants and proletarians.

By 1931, even the middle class had had enough of Spain’s backwardness. The king abdicated, another victim of the crisis of the Great Depression, and a Spanish Republic was established. A new Spanish constitution formed a presidential-parliamentary government with proportional representation, much like the Weimar Republic in Germany. Agrarian reform and limiting the temporal power of the Catholic Church divided the Spanish people and the liberals and socialists lost control of the government in 1933, when conservatives won the national elections. Rebellions by radical miners in northern Spain in 1934 led to repression and the imprisonment of thousands, leading to the formation of a “Popular Front” government in February 1936 after very close elections.

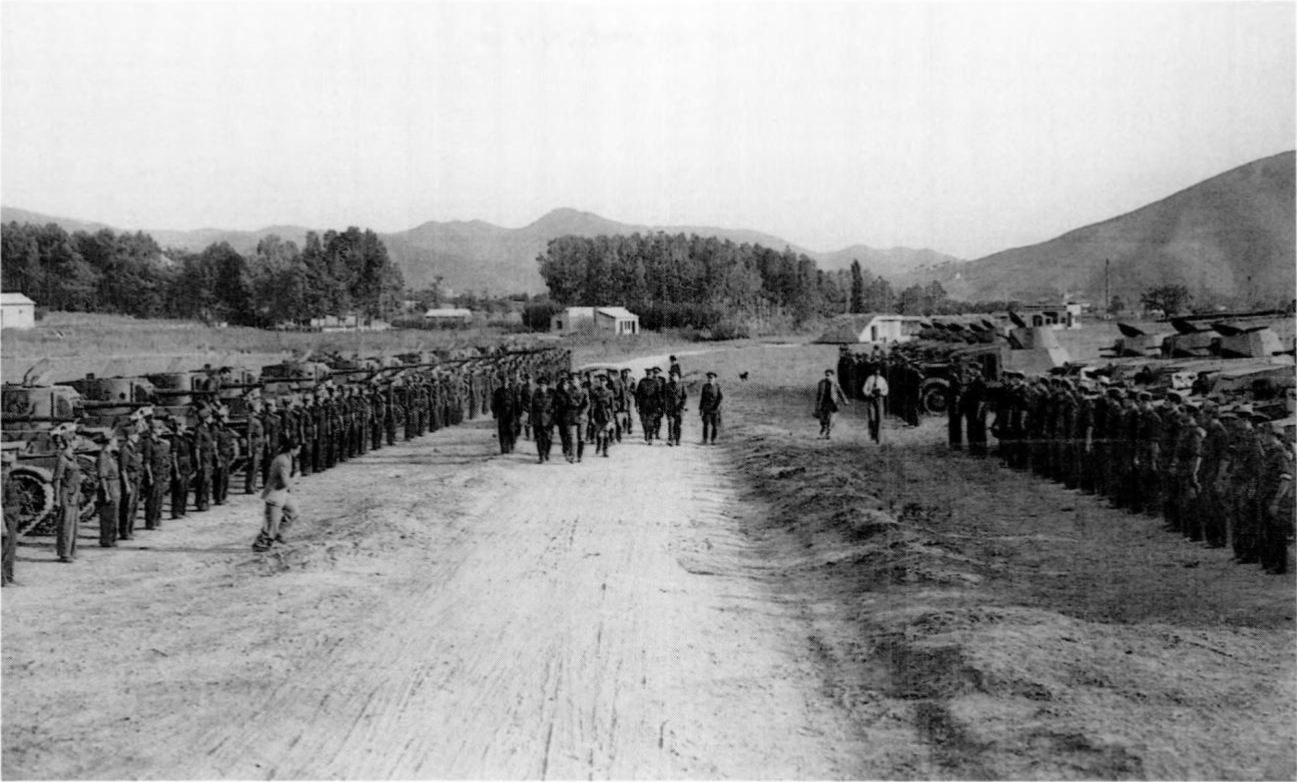

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the world’s communist parties to join anti-fascist Popular Front coalitions. The Spanish Popular Front government was a coalition of socialist, anarchist, and workers parties seeking to preserve and extend liberal reforms. However, when the new government rolled out agrarian reforms and began suppressing the Church, street fighting and assassinations led to a fascist-supported military coup orchestrated by General Francisco Franco in July, 1936. Although the “nationalists” took control of northern and western Spain, the fascists were stopped in the region around Madrid and Barcelona by socialist and anarchist workers who had been armed by the Republican government. A bloody civil war commenced.

Hitler and Mussolini immediately sent weapons, troops and air support to Franco, while Stalin supported the Republic. The leading European democracies, Great Britain and France, declared neutrality while the United States chose once again to try to stay out of Europe’s disputes. Individual British, French, and American volunteers arrived to fight for the Republic, hoping to make Spain “the graveyard of fascism”. However, even before Franco and the nationalists finally defeated the Republic in April 1939, Stalin had pulled Soviet advisors out of Spain and abandoned the Popular Front strategy. Francisco Franco remained the authoritarian dictator of Spain until his death in 1975.

Why this reaction from the victors of World War I? By the 1930s, the Great Depression, the French, British, and Americans were wondering what “winning” the Great War had really meant. The deaths of millions and the wounding of millions more did not seem worth repeating.

In October 1938, the British and French leaders, alarmed but still anxious to avoid war, attended the diplomatic conference in Munich. Interestingly, the Czechoslovak government had not even been invited to the conference in Munich; despite being the only democracy standing in Central Europe by 1938, they were betrayed by the appeasement policy of their fellow democracies.

Nor were the democracies moved by Nazi excesses against the Jews in Germany. In November 1938, after a German diplomat was assassinated by an exiled German Jew in France, the Nazi government allowed a massive outpouring of violence against Jews and Jewish-owned businesses. German mobs murdered dozens of Jews, publicly humiliated thousands, and burned businesses and synagogues. The Nazi-sponsored violence became known as Kristallnacht, “the Night of Broken Glass.” Many people in the democracies were outraged, thinking that such a pogrom was only impossible in a civilized nation like Germany. However, no government took action against Hitler, nor did any country accept Jewish refugees; anti-Semitism was all too common in most “civilized” countries.

All of this was happening as Stalin was still supporting the Spanish Republic, hoping that the democracies would join in a struggle against rising fascism. When they instead appeased Hitler, Stalin concluded that the capitalists perceived Hitler as a bulwark against the communist Soviet Union rather than as a threat to their own territories and interests. The Soviet Premier changed his diplomatic strategy and on August 23, 1939 signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany. By that time, Hitler had set his sights on “liberating” the German-speaking population in Poland and their territory. German troops poured across the border on September 1, 1939. The world learned of the secret agreement to divide Poland included in the Nazi-Soviet Pact when the Stalin sent his armies into eastern Poland three weeks later.

The Road to War in East Asia

As described in the previous chapter, the government ruling in the name of Japanese Emperor Hirohito also shifted toward fascism after the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the establishment of the puppet state Manchukuo in northeast China and Inner Mongolia. Manchukuo provided Japan with the benefits of an imperial colony: raw materials for Japanese industries that were not available on the islands of Japan and a captive market for Japanese goods. The Japanese military also justified their conquests by claiming they were liberating Asia from European colonialism. Not all the Asian territories they invaded, however, were happy to become part of the Japanese “Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=klAjaujdE6M

Now, we’ve gotten a bit ahead of ourselves towards the end there but it’s important to note… Let’s back track for a bit to the Second Sino-Japanese war. Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China on July 7, 1937, and the broken Chinese army gave up Beijing to the Japanese on August 8, Shanghai on November 26, and the Nationalist capital, Nanjing, on December 13. In the first six weeks after capturing the capital, Japanese troops… “Viewer discretion is advised”

The United States lacked both the will and the military power to oppose the Japanese invasion, and even continued to sell oil and scrap iron to Japan. The Japanese army was a technologically advanced force consisting of 4,100,000 men and 900,000 Chinese collaborators armed with modern rifles, artillery, armor, and aircraft. By 1940, the Japanese navy was the third-largest and among the most technologically advanced in the world. Still, Chinese Nationalists lobbied Washington for aid. Chiang Kai-shek’s popular wife, U.S.-educated Soong May-ling, known to Americans as Madame Chiang, led the effort. In contrast to her gruff husband, Madame Chiang was charming and able to use her knowledge of American culture and values to garner support for Chiang and his government. However, although the United States denounced Japanese aggression, it took no action.

As the Nationalists fought for survival, Mao Zedong recognized the power of the Chinese peasant population and began recruiting from the local peasantry, capitalizing on the outrage caused by both the Nationalist failure to prevent Japanese invasion and its scorched-earth retreat. Mao gradually built his force from a meager seven thousand survivors at the end of the Long March in 1935 to a robust 1.2 million members by the end of the World War II.

1940-1942: Axis Conquests in Europe and Asia

Two days after the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France declared war and began mobilizing their armies. The war planners hoped the Poles would be able to hold out for three to four months, enough time for the Allies to intervene. Poland fell in three weeks, partly due to the Russian invasion in the east and partly due to a new form of warfare. The German army, anxious to avoid the rigid, grinding war of attrition in the trenches of World War I, had built its new army for speed and maneuverability. German strategy emphasized the use of tanks, planes, and motorized infantry to concentrate forces, smash front lines, and wreak havoc behind the enemy’s defenses. It was called Blitzkrieg, “lightning war.”

After conquering eastern Poland, Stalin’s armies shifted focus to occupying the Baltic States, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, and to invading Finland. The Soviet leader was planning to reestablish the borders of the former Tsarist Russian Empire. However, the invasion of Finland met stubborn resistance and winter; the conflict ended with the Finns losing only a bit of territory on their southeastern borders.

Meanwhile, after the fall of Poland, France and Britain braced for the inevitable German attack. In April 1940, the Germans quickly conquered Denmark and Norway in an effort to prevent the British naval blockade which had been so key to the German defeat in World War I. The following month, Hitler launched his blitzkrieg into Western Europe through the Netherlands and Belgium to avoid well-prepared French defenses along the French-German border. Poland had fallen in three weeks; France lasted only a few weeks more. By June, Hitler was posing for photographs in front of the Eiffel Tower. In another propaganda victory, Hitler made the French diplomats sign their surrender in the same railroad car used for the German surrender in the First World War.

Germany split France in half, occupying the north and allowing a collaborationist government to form in Vichy to govern the south and the French colonies. Led by the “Hero of Verdun,” Marshal Philippe Petain, the Vichy regime sought to reorganize France along authoritarian fascist lines. Significant support for Germany by the French right was one of the reasons for their defeat in June 1940. Many in France had also abandoned democracy and welcomed the demise of the Third Republic. If the future held a German-dominated Europe, they reasoned, then it would be better for France to collaborate as partners rather than as subjects in a new Nazi empire. Although this rationalization fit into the scheme proposed by German propaganda, Hitler would never allow a full partnership with any of the conquered peoples.

With France under control, Hitler turned to Britain with Operation Sea Lion, and the German Luftwaffe. British pilots won the so-called Battle of Britain, saving the islands from invasion and prompting the new prime minister, Winston Churchill, to declare, “Never before in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.” Frustrated by losing the Battle of Britain, Hitler began a bombing campaign against cities and civilians; The Blitz.

In June 1941, German forces crossed into the Soviet Union in a massive surprise attack. “Operation Barbarossa” was the largest land invasion in history and Germany hoped to use the same Blitzkrieg tactics to break Russia before the winter. The German military caught the Red Army and Stalin unprepared and quickly conquered enormous swaths of land and captured nearly three million prisoners. However, Russia was too big! After recovering from the initial shock of the German invasion, Stalin moved his factories east of the Urals, out of range of the Luftwaffe. He ordered his retreating army to adopt a scorched earth policy, destroying food, rails, and shelters to slow the advancing German army.

The German army split into three forces and reached the gates of Moscow and Leningrad, but their supply lines stretched thousands of miles. Soviet infrastructure had been destroyed, partisans harried German lines, and the brutal Russian winter arrived. Germany had won massive gains but the winter found German troops exhausted and overextended. In the north, the German army starved a million and a half people in Leningrad to death during an 827-day siege that has been called a genocide. In the center, on the outskirts of Moscow, the German army faltered and fell back after a three-month battle that killed a million people.

While Hitler marched across Europe, the Japanese continued their war in the Pacific…

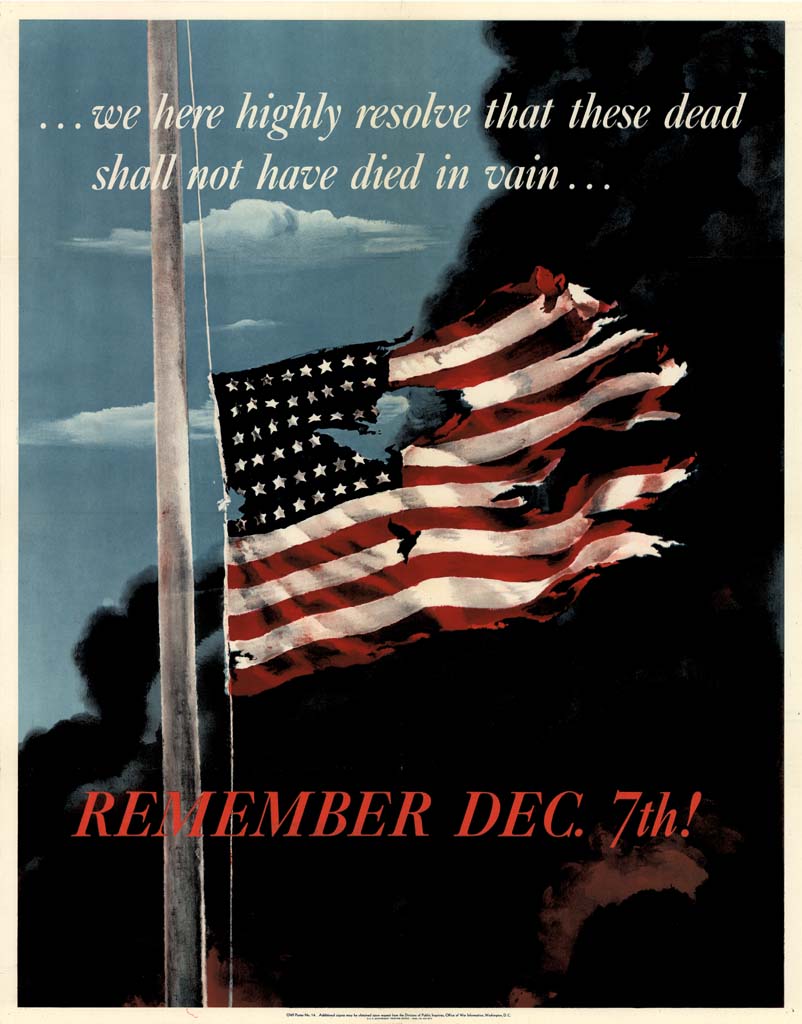

American isolationism fell at Pearl Harbor. Japan also assaulted Hong Kong, the Philippines, and American holdings throughout the Pacific, but it was the attack on Hawaii that threw the United States into a global conflict. Germany and Italy declared war on the US on December 11th. Within a week of Pearl Harbor the United States was at war with the entire Axis, turning two previously separate conflicts into a true world war.

After Pearl Harbor, Japan conquered the American-controlled Philippine archipelago. After running out of ammunition and supplies, the garrison of American and Filipino soldiers surrendered. The prisoners were marched eighty miles to a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp without food, water, or rest. Ten thousand died on the Bataan Death March.

Japan had hoped the United States would be unable to respond quickly…

After the U.S. officially entered the war, Hitler unleashed U-boat “wolf packs” into the Atlantic Ocean with orders to sink anything carrying aid to Britain. After losing thousands of merchant ships in 1942 and early 1943, British and U.S. tactics and technology won the Battle of the Atlantic. By mid-1943, Hitler’s navy was losing ships faster than they could be built. Soon the wolf pack was sheltering in a defensive crouch in the harbors of occupied Europe.

Allied Victories

When Hitler renewed his invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1942, he focused on conquering the bread basket and oil fields of southern Russia. The Blitzkrieg again brought rapid success, but again got too far ahead of its supply lines. Although the strategy included sophisticated tanks, armored troop carriers, and dive bombers, the Germans still used horse-drawn wagons to bring up food, ammunition and spare parts to the advancing armies. As the advance slowed, Axis armies arrived at the new industrial city on the Volga River, Stalingrad. Hitler badly wanted to conquer and wipe out Stalin’s namesake city, and the Soviet Premier was just as determined to defend it. In late 1942, the two armies bled themselves to death in the destroyed city; fighting house to house in a five-month battle that killed nearly two million people on both sides. Stalin placed his trust in General Georgy Zhukov, who planned a brilliant Soviet pincer move, cutting off the German 6th army in Stalingrad. When his army was forced to surrender in February 1943, Hitler was apoplectic in his anger and his generals began to doubt that he any longer had the strategic brilliance he showed in the previous years.

The Germans planned to follow up with renewed attacks to get at Soviet oil, but their battle with the Red Army at Kursk turned the course of the war definitively to the Soviets. Zhukov correctly guessed the German strategy, and fortified Kursk while massing armies to the north and south. After the greatest tank battle in world history, Zhukov unleashed another pincer move, and the Germans retreated from battle as quickly as they could. The Red Army began rolling westward, putting the Germans permanently on the defensive for the remainder of the war. More than any other Ally, the Soviet Union was most responsible for defeating Hitler, but at great sacrifice. Twenty-five million Soviet soldiers and civilians died in what Russians call the Great Patriotic War, and roughly 80 percent of all German casualties during the war came on the Eastern Front.

Allied victories in North Africa in 1942 also reversed Axis gains. Hitler’s decision to invade southern Russia was based on the expectation that the Middle East would soon fall into Axis hands. In November, the first American combat troops entered the European war, landing in French Morocco, where French Vichy forces switched sides and joined the struggle to defeat the Axis. The Americans pushed the Germans and Italians eastward while the British, after defeating Rommel at El Alamein in Egypt, began rolling the Axis armies back to the west. By early 1943, the Allies had pushed Axis forces into Tunisia and then out of Africa. Then the US turned to dealing with Japan…

In January 1943, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met at Casablanca to discuss the next step of the European war. The meeting leaders also declared that they expected nothing short of unconditional surrender from the Germans; to assure Stalin, who still did not trust the Allies to keep their word. At Casablanca, Churchill convinced Roosevelt to chase the Axis up the Italian peninsula, into the “soft underbelly” of Europe. Stalin preferred a cross-Channel invasion of France, but the British and Americans were not yet prepared in 1943. In July, Allied forces led by General Dwight Eisenhower crossed the Mediterranean and landed in Sicily. The Italian King dismissed and arrested Mussolini, who escaped with Germany’s help and established a fascist government in northern Italy. The south, however, switched sides and fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war. However, the advance northward toward Europe’s “soft underbelly” turned out to be much tougher than Churchill had imagined. Italy’s narrow, mountainous terrain and Mussolini’s newly-formed fascist state gave the defending Axis the advantage. Movement up the peninsula was slow, and in some battles, conditions returned to the trench-like warfare of World War I as the German armies fell back to new defensive positions, exhausting Allied forces in one battle after another. It would take nearly a year to capture Rome, and northern Italy was not liberated until the last weeks of the war in 1945.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) sent thousands of bombers to England and North Africa in preparation for a massive strategic bombing campaign against Germany; another move to assure Stalin the Allies were opening a “second front” against Germany. The Allies’ plan was to bomb German cities around the clock. Initially, U.S. bombers focused on destroying German ball-bearing factories, rail yards, oil fields, and manufacturing centers during the day because the U.S. was reluctant to target civilians in terror bombings. However, after the London Blitz, the British felt no compunction against retaliating in kind, and carpet-bombed German cities at night. By the end of 1944, the Americans joined the British in the same strategy, bombing urban industrial targets despite massive civilian casualties. The joint RAF-USAAF bombing of the industrial city, Dresden, in February 1945, dropped 3,900 tons of high explosives on the city, causing a firestorm that killed 25,000 civilians.

Historians still debate the effectiveness of the Allied bombing campaign against both Germany and Japan, and the overall usefulness of bombing civilians in World War II… The Germans actually increased production of war materiel during the war, relocating factories and streamlining production. German and Japanese civilians, like the Londoners in 1940, learned to live with aerial attacks instead of rising up to overthrow their own governments and sue for peace. Critics of terror-bombing argue that targeting civilians rarely results in surrender, and instead often stiffens a country’s resolve to fight on and inflict the same terror on its foe.

In the wake of the Soviet victory at Stalingrad, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met in Tehran in November 1943. An invasion of France was tentatively scheduled for May 1944. The leaders also began post-war planning, considering the best ways to prevent another world war and Great Depression. The Allies had already begun calling themselves the “United Nations,” especially as Latin American republics and other countries began joining the fight against the Axis. In April 1945, diplomats gathered in San Francisco to design a way for the United Nations to address world problems in a post-war world.

To avoid another Great Depression and to reconstruct war-torn nations, in 1944 the Allies also sent representatives to the Bretton Woods resort in New Hampshire to forge new international financial, trade, and developmental relationships. The results of both conferences will be discussed below, but it is important to notice that both international meetings were held in the United States. Americans had become convinced that isolationism was not longer a practical foreign policy, and the world recognized that the U.S. was going to be instrumental in a post-war effort to keep the peace.

The Conclusion

On the same day the American army entered Rome, American, British and Canadian forces launched Operation Overlord, the long-awaited invasion of France; D-Day, as it became known. The Allied landings at Normandy were successful, and by the end of the month 875,000 Allied troops had arrived in France. Paris was liberated in late August.

The Nazi armies were crumbling on both fronts. Hitler tried to turn the war in his favor in the west. The Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 and January 1945 was the largest and deadliest single battle fought by U.S. troops in the war. The desperate Germans failed to drive the Allies back from the Ardennes forests to the English Channel, but the delay cost the western-front Allies the winter. The invasion of Germany would have to wait, while the Soviet Union continued its relentless push from the east, ravaging German populations in retribution for German war crimes. German counterattacks failed to prevent the Soviet advance and 1945 dawned with the end of European war in sight.

In February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met again at Yalta, located on the Crimean Peninsula in the Black Sea. Roosevelt and Churchill were anxious for Soviet help in defeating Japan; the atom bomb was months away from being tested and no one knew whether it would work. Stalin agreed to join the fight in Asia against Japan three months after peace was declared in Europe.

Soviet troops reached Germany in January 1945, and the Americans crossed the Rhine in March. In late April, American and Soviet troops met at the Elbe River while the Soviets pushed relentlessly to reach Berlin first and took the capital city in May. A few days before their arrival, Hitler and his high command committed suicide in a city bunker. Germany was conquered and the European war was over.

A changed set of Allied leaders met again at Potsdam, Germany. Of the “Big Three” who had met at Yalta, only Stalin was at Potsdam for the whole conference. Roosevelt had died of natural causes in early April and Churchill was replaced by new Prime Minister Clement Atlee in the early days of the meeting when his Conservative Party was defeated at the polls by the Labour Party. The leaders agreed that Germany would be divided into pieces according to current Allied occupation, with Berlin likewise divided.

The Holocaust

Pacific War

As the Allies, especially the Americans, celebrated V-E (Victory in Europe) Day, they redirected their full attention to the still-raging Pacific War. In 1944 and 1945, the Japanese military continue to fight tenaciously in defeat after defeat. Few battles were as one-sided as the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, a Japanese counterattack that the Americans called the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot for the number of planes and vessels that they sank. At Iwo Jima, an eight-square-mile island of volcanic rock upon which the Americans wanted to build an airfield from which to attack Japan, seventeen thousand Japanese soldiers held the island against seventy thousand Marines for over a month. At the cost of nearly their entire force, they inflicted almost thirty thousand casualties before the island was lost in early 1945.

By that time, American heavy bombers were in range of the Japanese homeland. Bombers hit Japan’s industrial facilities but suffered high casualties. To spare bomber crews from dangerous daylight raids and to achieve maximum effect against Japanese morale, American bombers began night raids, dropping incendiary weapons that created massive firestorms consuming the wood-and-paper houses of the residential neighborhoods. Over sixty Japanese cities were fire-bombed; one hundred thousand civilians in Tokyo died in a single attack in March 1945.

In June 1945, after eighty days of fighting and tens of thousands of casualties, the Americans captured the island of Okinawa. The homeland of Japan was open before them. Okinawa was a viable base from which to launch a full invasion of the Japanese homeland and end the war. Estimates varied, but given the tenacity of Japanese soldiers fighting on islands far from their home, some officials expected that an invasion of the Japanese mainland could cost half a million American casualties and kill millions of Japanese civilians.

Historians debate the many motivations that drove the Americans to use atomic weapons against Japan and many American officials criticized the decision at the time. Government leaders and military officials cited the casualty estimates of an invasion to justify their use. Early in the war, fearing that German scientists might develop an atomic bomb, the German-Hungarian-American physicist Leó Szilárd had written a letter to Franklin Roosevelt which Albert Einstein signed, warning of a nuclear-armed Hitler. After some debate, other American physicists acknowledged the possibility. The U.S. government responded in 1942 with the Manhattan Project, a hugely expensive, ambitious program to create a single weapon capable of leveling an entire city.

In addition to the American atom bomb attacks, on August 9th, Soviet forces invaded Manchuria and overthrew the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. On August 10th, Japanese cabinet ministers agreed to the Allied terms for surrender. Emperor Hirohito endorsed their decision on August 15 and announced the surrender of Japan. On September 2, aboard the battleship USS Missouri, delegates from the Japanese government formally signed their surrender. World War II was finally over.

U.S. Industry and the “Home Front”

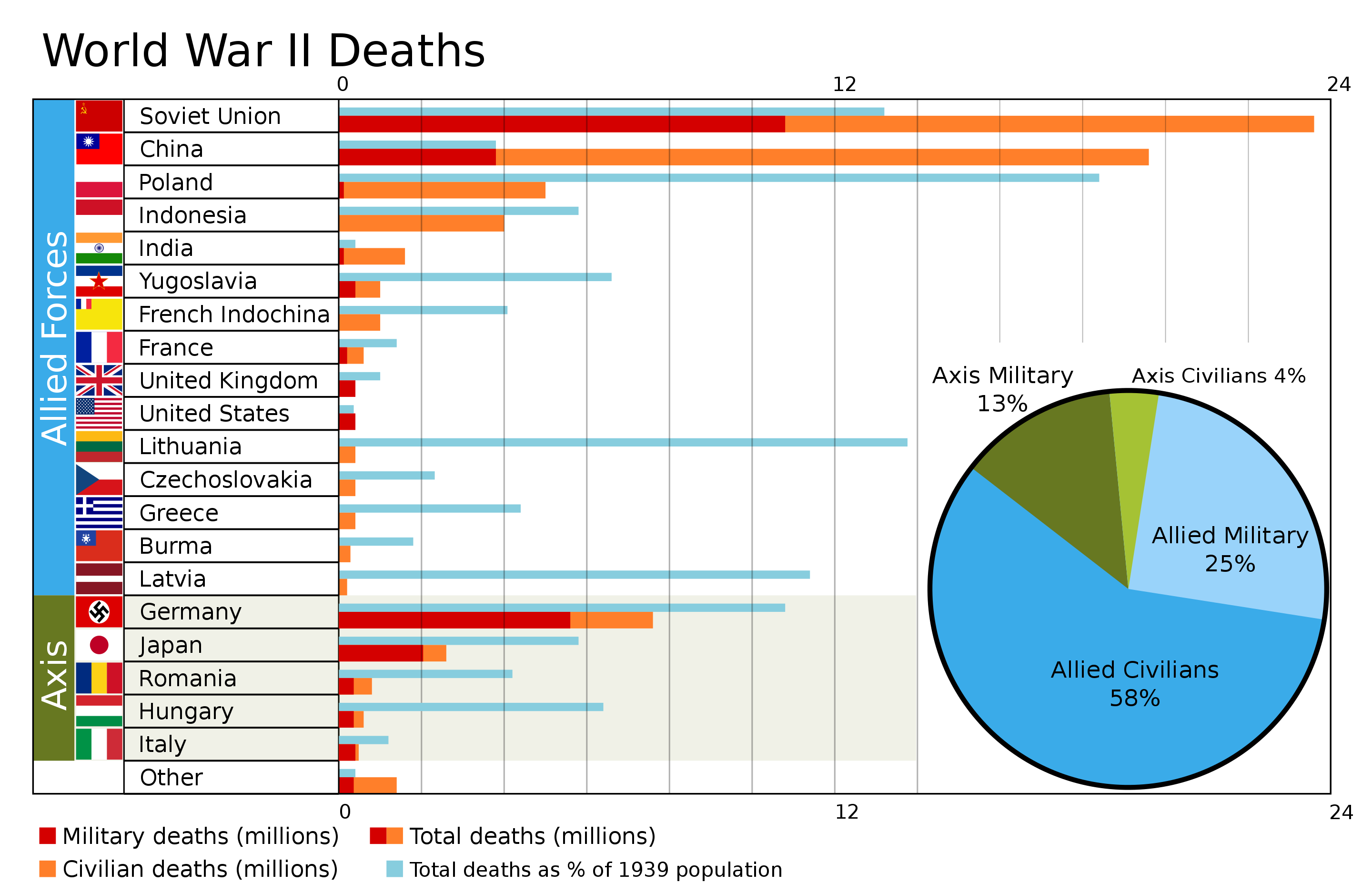

The US was lucky that none of the war was fought on American soil, but 419,400 US servicemen died in the conflict. World War II was the deadliest war in history. Military deaths were over 25 million, including 5 million prisoners of war who died in custody. The war also killed about 55 million civilians, including 28 million who died of war-related disease and famine. The number of wounded has not been accurately documented, but was probably similar to or greater than the death toll. More than half those casualties were in Russia and China. The Chinese death toll was at least 20 million. The Soviet Union lost 11,400,000 men in battle, 10 million civilians in war-related activities, and about 7 million through famine caused by the war, for a total of about 28 million. These losses amounted to about 14% of the U.S.S.R.’s 1940 population. Germany lost over 5 million soldiers and up to 3 million civilians.

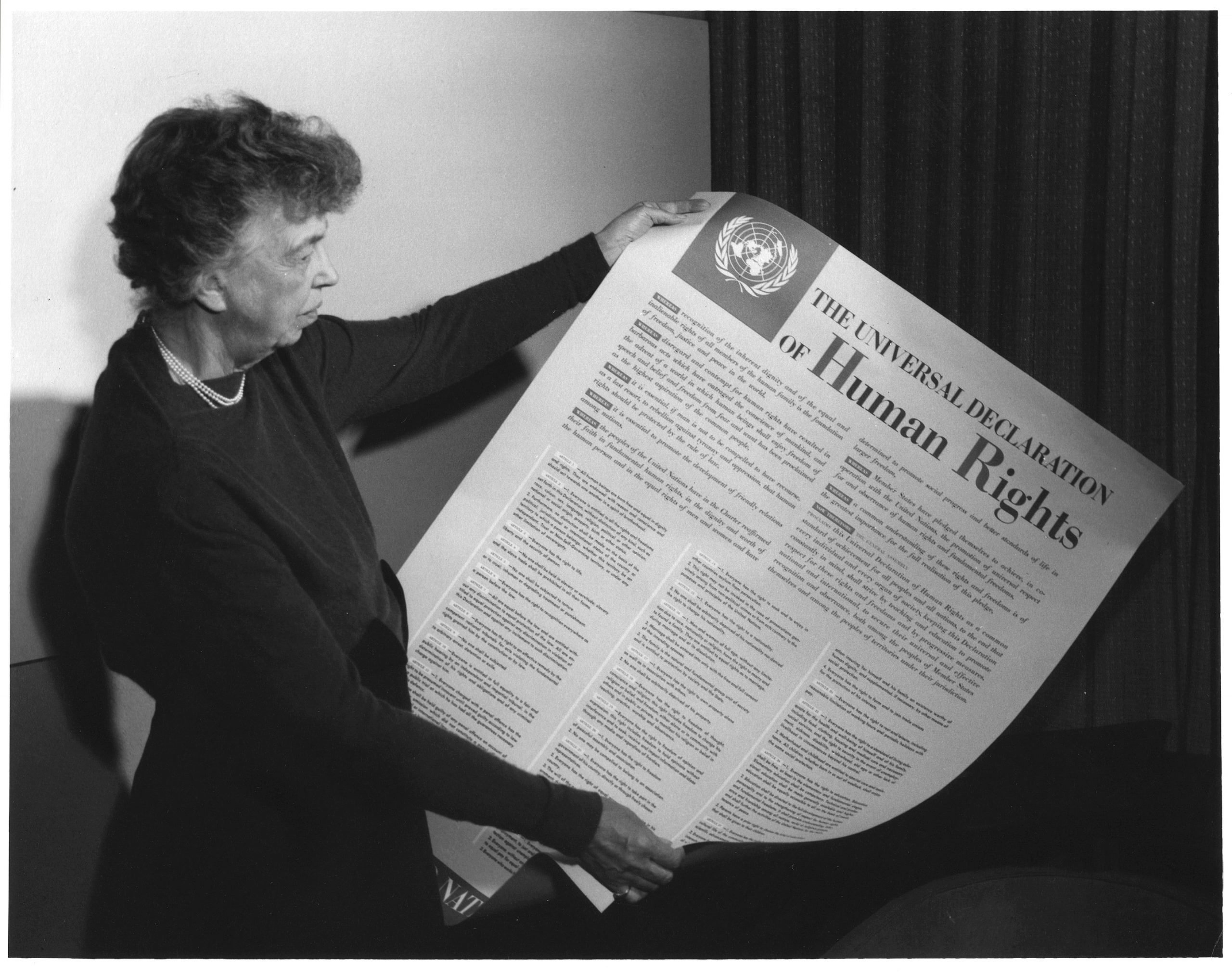

Americans celebrated the end of the war after V-J Day in August 1945. At home and abroad, the United States wanted a postwar order that would guarantee global peace and domestic prosperity. Although the alliance of convenience with Stalin’s Soviet Union would rapidly collapse, Americans nevertheless looked for the means to ensure postwar stability and economic security for returning veterans. The inability of the League of Nations to stop German, Italian, and Japanese aggressions caused many to question whether any global organization could effectively ensure world peace. Skeptics included Franklin Roosevelt, who, as Woodrow Wilson’s undersecretary of the navy, had witnessed the rejection of The League’s ideal of world governance by both the American people and the Senate.

In 1941, Roosevelt believed postwar security could best be maintained by an informal agreement between what he termed the Four Policemen: the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and China. But others, including Roosevelt’s secretary of state Cordell Hull and British prime minister Winston Churchill, convinced the president to push for a new global organization. As the war ran its course, both Roosevelt and the American public came around to the idea of the United Nations. Pollster George Gallup noted a “profound change” in American attitudes. In 1937 only a third of Americans polled supported the idea of an international organization. But as war broke out in Europe, half of Americans did. America’s entry into the war bolstered support, and by 1945, 81 percent of Americans favored the idea.

And Franklin Roosevelt had always supported the ideals enshrined in the United Nations charter. In January 1941, he described Four Freedoms that all of the world’s citizens should enjoy: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Roosevelt signed the Atlantic Charter with Churchill, reinforcing those ideas and adding the right of self-determination and promising some sort of economic and political cooperation. Roosevelt first used the term united nations to describe the Allied powers, not the subsequent postwar organization. But the name stuck.

At Tehran in 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill convinced Stalin to send a Soviet delegation to a conference in August 1944, where they agreed on the basic structure of the new organization. It would have a Security Council consisting of the original Four Policemen and France, that would consult on how best to keep the peace and when to deploy the military power of the assembled nations. In a shift from the unarmed diplomacy of the League of Nations, the U.N. would have a military. The plan was a hybrid between Roosevelt’s policemen idea and a global organization of equal representation. There would also be a General Assembly made up of all nations, an International Court of Justice, and a council for economic and social matters. The Soviets expressed concern over how the Security Council would work, but the powers agreed to meet again in San Francisco between April and June 1945 for further negotiations. There, on June 26, 1945, fifty nations signed the U.N. charter.

Knowledge Check:

As mentioned, at the end of World War I the people took a 20 year time-out and went right back to it with World War II. Now we know what happened in those 20 years and how we got through World War II…

- The Road To War in Europe

- What were the main causes of World War II?

- How did racism play an early role in fascist expansionism?

- Why did Stalin support the Spanish Popular Front?

- Why did the European democracies try to appease Hitler?

- Was Stalin wrong to sign a non-aggression pact with Germany?

- The Road To War in East Asia

- What would you say to Japanese leaders today who claim the Rape of Nanjing never happened?

- Do you think Chiang Kai-Shek was an effective leader of the Kuomintang?

- 1940-1942: Axis Conquests in Europe and Asia

- How was Hitler able to surprise Stalin with Operation Barbarossa?

- Why was the Blitzkrieg strategy that had worked so well in Europe less successful in Russia?

- Did Japan make a strategic error, attacking the United States?

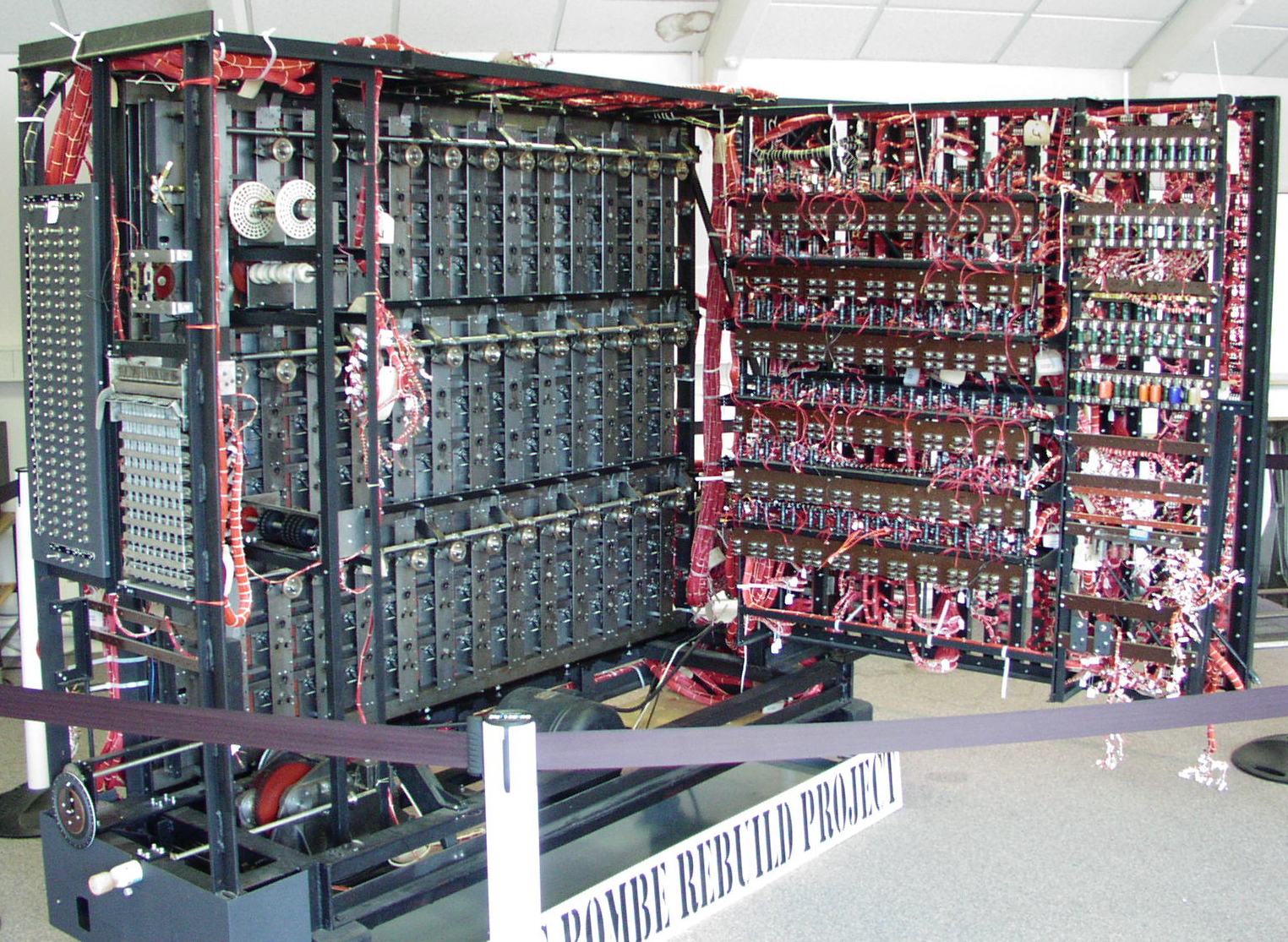

- Reflect on the technological developments that were accelerated by the war.

- Allied Victories

- How did the different wartime experiences of the Allies influence the goals of the “Big Three” leaders, Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt?

- If terror-bombing civilian populations is ineffective, why did everyone continue doing it?

- The Conclusion

- D-Day is an iconic moment for Americans. What do you think similar moments would be for Britain and the Soviet Union?

- Why did the U.S. and U.S.S.R. race to reach Berlin?

- The Holocaust

- Why was the German killing of 11 million people in the Holocaust so difficult for people to believe?

- What do you think motivates people who insist the Holocaust didn’t happen?

- Pacific War

- How was the Pacific war different from the European war?

- Was the U.S. justified in dropping atomic bombs on Japan?

- US Industry and The “Home Front”

- How were the experiences of women and African Americans during the war similar?

- How were they different?

- How did racism and prejudice affect the U.S. response to the Jewish refugee problem and Japanese internment?

- How much of a role do you think government assistance to veterans through the G.I. Bill played in the post-war era?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- Marines_with_LVT(A)-5_in_Iwo_Jima_1945 © Fifth Marine Division photographer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Selassie_on_Time_Magazine_cover_1930 © Time Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Soviet_armor_in_the_spanish_civil_war © Textidor is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- GUERNICA © Picasso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H27337,_Moskau,_Stalin_und_Ribbentrop_im_Kreml © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 2880px-Manchukuo_map_1939.svg © Emok is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- service-pnp-fsa-8d13000-8d13900-8d13979v © Roberts is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H25217,_Henry_Philippe_Petain_und_Adolf_Hitler © Bundesarchiv is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Remember_december_7th © Allen Saalburg is licensed under a Public Domain license

- OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA © Tom Yates is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- cmp3.10.3.3Lq4 0xad6b4f35 © Grigory Vayl is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tehran_Conference,_1943 © US Army is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 3c-Iwo_Jima © US Post Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Childsoldier_In_Okinawa © 米国連邦政府 - 米国連邦政府 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-World_War_II_Casualties2.svg © Oberiko is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license