10 Decolonization

Chapter Outline:

Thus far, we’ve discussed the rise of civilization and the metamorphosis of a few into empires. We then watched as they crumbled into chaotic revolutions and world wars. Yet, in all this we have glossed over the ripple effects these times have had on the colonies dragged along for the ride. Let us now turn to their “decolonization”!

- Questioning Imperialism

- Independence and Partition of British India

- Israel

- “British” Kenya

- “French” Algeria

- “French” Indochina

- New Nations & Development

- The Green Revolution

The defeat of Germany and Japan freed the people of the nations these would-be empires had conquered, but it also caused people dominated by older empires to question the legitimacy of imperialism. Yet, we must note that the struggle for independence had begun long before World War II. Imperial justifications that people such as Britain’s subjects in India and the America’s in the Philippines were unprepared to stand on their own as independent nations were destroyed by the effectiveness of the Indians and Filipinos in World War II. Filipinos had proven their value as guerrilla fighters after the Japanese invasion. And in imperial possessions like India, the “civilizing project” had given the knowledge and wherewithal to the locals on running their own nations; it was time for the imperialists to leave. Furthermore, the war was full of inspirational examples of Europeans and Asians who fought side by side against the fascist occupiers in their conquered nations. A process accelerated by the strain of war on the European imperialists.

After the war, the nations that had been targeted by Germany (Britain, France, and the Netherlands) all attempted to separate their reaction to this attack from the response of colonial populations to their return. For instance, British leaders like Winston Churchill hoped and expected to expand their empire, which they now renamed a commonwealth, and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP) had no intention of giving back Iran’s oil fields. This may seem a strange attitude for a nation that was having trouble feeding and housing its own population and leaned on U.S. aid like a crutch. Yet, the British retained their sense of cultural superiority and convinced themselves that their help was still needed to “assist primitive peoples in their march to modernity.”

The timing of national liberation was complicated by the growing conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union; known as the “Cold War.” Each superpower was busy competing and recruit more new nations to “their side“, pouring military and economic aid into the new developing countries.

Despite the Cold War, at times the process of independence was peacefully achieved through mutual agreement. In the Philippines, for example, the U.S. government handed over power to a local Filipino government within a year of ending the war with Japan. President Harry Truman recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946. Arrangements were made, allowing the U.S. to retain dozens of military bases and for American businesses to have preferential access to the raw materials and markets of the newly independent nation.

Sometimes, peaceful political pressure from organized movements also led to liberation. Indian independence, examined below, is the first and prime example of how non-violent protest, boycotts, and moral suasion could result in freedom. However, there are also many cases in which independence could only be achieved through a more violent guerrilla struggle, as European imperialists were unwilling to let go of their colonies despite the desires of the colonized.

Independence and Partition in British India

Israel

Weariness with war and terror, and a desire to qualify for U.S. military and economic aid, have led the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan to recognize Israel in 2020. But it is one thing to have recognition from a government, and another thing to be accepted as a nation by the “Arab Street”. Ordinary Arab people are often tired of authoritarian rule in their own countries, and are more supportive of the Palestinian Arab cause than the governments ruling them.

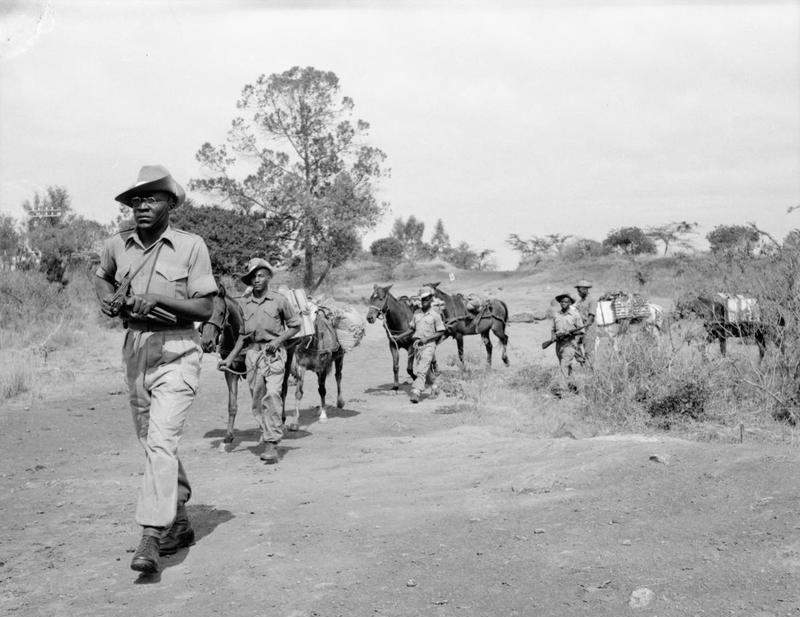

“British” Kenya

Although Great Britain had retreated relatively peacefully from India and had given up its control over Palestine voluntarily, this was not the universal pattern. Reluctance to abandon colonies was especially a problem in Africa, where there were British settlers rather than administrators. By the early twentieth century, 30,000 British settlers occupied all the best farmland in Kenya, which they had bought or had been assigned by the colonial government, leaving 5 million Kenyans without. The attitude of British farmers in Kenya was much like the relationship two centuries earlier between English colonists in North America and the Native Americans.

However, this was the twentieth, not the eighteenth century. In Kenya, a resistance movement called Mau Mau began in 1952 when natives restricted to reservations in their own country revolted. After World War II, 1.25 million Kikuyu had 2,000 square miles of marginal farmland to feed themselves while 30,000 British settlers had 12,000 square miles in the fertile hills of the Central and Rift Valleys, where they grew cash crops like coffee using native labor. The Mau Mau uprising protested this injustice and the British colonial government responded. Declaring a state of emergency, the British moved about 450,000 Kikuyu to concentration camps and another million were restricted to “enclosed villages”. Prisoners suspected of being Mau Mau fighters were often tortured by British troops (typically they were flogged to death, burned alive, or castrated). In June 1957 the British attorney general of the colony wrote to the governor that the mistreatment of captives was “distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia.” He reminded the governor, “if we are going to sin, we must sin quietly.”

The uprising lasted until 1963, partly because white settlers could not easily abandon their property and go back to Britain. Power in Kenya eventually shifted from the British colonial government to a native government, initially made up of many members of the Kenyan African National Union (KANU) that had led the resistance. Its leader, Jomo Kenyatta, became Kenya’s first indigenous Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and was President of Kenya and led the KANU party until his death in 1978. Kenyatta, like other leaders such as Gandhi and Ho Chi Minh, had travelled internationally. He attended the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow as well as University College in London and the London School of Economics, although when the press mentioned him, they typically observed he had “studied in Russia”. Kenyatta was imprisoned from 1954 to 1961 for allegedly leading the rebellion, and became leader of the party and the nation when released. Kenyatta initially tried to heal the nation by downplaying the atrocity of the recent war, and he welcomed the multinational corporations that dominated the Kenyan economy. The government helped African farmers buy out white landowners and expanded education and social support programs. Kenyatta was often accused of being a socialist, but he was also hated by the British settlers for being married to a white woman. His economic policies balanced capitalism and social welfare. Kenyatta was regarded by many Africans as a strong Pan-Africanist and was hailed as the Hero of the Kikuyu. The current (2022) president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, is his son.

“French” Algeria

The British were not the only Europeans to lose their colonial empires. Although France had been conquered and occupied by Germany, after the war the French fully expected to regain their colonial possessions in Africa and Asia and resume where they had left off. Their subject peoples in the colonies had different ideas. In Algeria, revolutionaries mobilized and an Algerian People’s Manifesto was published in 1943. On the morning of May 8, 1945, VE Day, a parade of about 5,000 Muslim Algerians celebrating the war’s end was met by armed French police. Marchers and police exchanged gunfire and during the battle people on both sides were shot. A few days later a smaller, peaceful protest by the Algerian People’s Party was violently repressed by police. Rural Algerians responded by attacking ethnic French settlers, called pieds noirs, killing 102 Europeans. The French retaliated, killing between 6,000 and 30,000 Algerians.

The Algerians did not forget this massacre and nearly a decade later, on November 1, 1954, Algerian guerrilla forces attacked civilian and military targets throughout the country. The National Liberation Front (FLN), encouraged by the fact France had just lost their colony of French Indochina, called on Muslims in Algeria to join in the struggle for independence. The FLN applied guerrilla “hit and run” tactics as well as terrorism and torture of both French pieds noirs and Africans suspected of supporting the regime. The French were equally brutal, and by 1956 there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria.

The war lasted eight years and killed over a million people. The French military lost 25,000 troops and about 3,000 European civilians were killed. French officials estimated the Algerian death toll at 350,000, but other French and Algerian estimates range from 960,000 to 1.5 million. The United States recognized Algeria’s independence in September 1962 and the country became the 109th member of the U.N. in October.

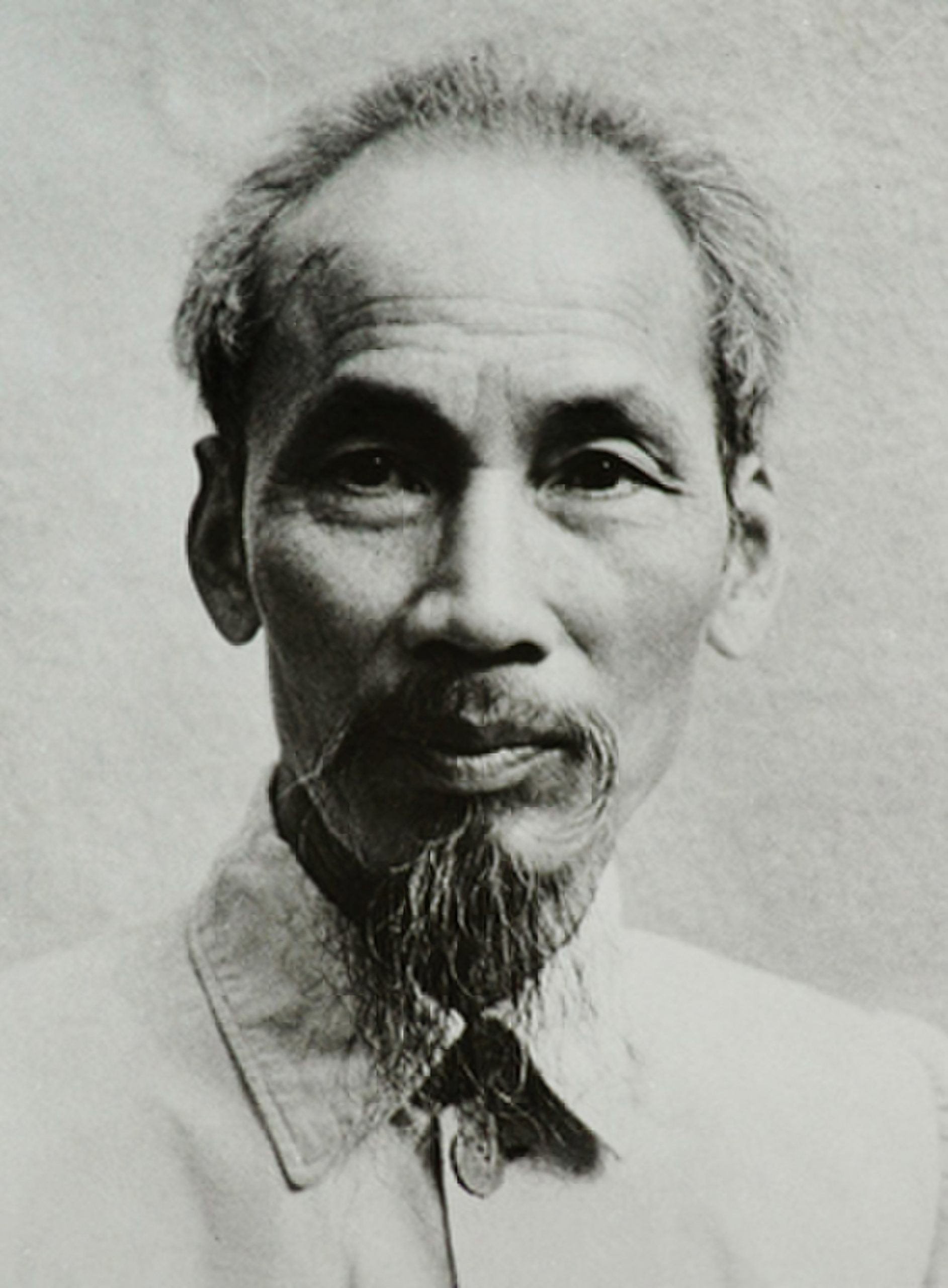

“French” Indochina

France had also expected to return to power in its colonies in French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), but revolutionaries, led by Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), had other ideas…

In 1941 Ho returned to Vietnam to lead the independence movement there. The Japanese invasion created an opportunity for the patriots, who were aided in their resistance of the Japanese and Vichy French by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. At the end of World War II, Ho wrote a declaration of independence for Vietnam based on the US Declaration from 1776. Ho repeatedly petitioned President Harry S. Truman to recognize Vietnam, citing the Atlantic Charter, but Truman never responded. Meanwhile, British and Chinese troops occupied the country in support of France. Vietnamese rioted and killed a hundred or so French citizens, and in retaliation French troops armed Japanese prisoners of war and massacred over 6,000 Vietnamese. This was the same pattern of asymmetrical force used by empires against their subjects throughout the colonial period. However, the story of Vietnam is only half over; we will return to it in the next chapter when we discuss the Cold War.

Kenya, Algeria, and Vietnam were not the only places where the imperial powers and their international allies responded violently to movements of national liberation among the colonized. For example, the French killed 80,000 in Madagascar in 1947 when the people of that island supported independence. The Indonesian War of Independence raged from the former Dutch East Indies declaration of independence in 1945 and The Netherlands’ recognition of their claims in 1949. About 8,000 Dutch troops and their allies were killed, and about 100,000 Indonesians. And growing fears of international communism pushed the United States government into supporting some of these actions. Although the Americans had peacefully let go of the Philippines, the U.S. military helped Korean militias massacre about 60,000 members of a peasant insurgency. The Korean Peninsula had been divided at the end of World War II, like Germany, into Soviet and U.S. occupation zones. Unsurprisingly, the two rivals backed communist and non-communist leaders in North and South Korea. The resulting conflict, the Korean War (1950-1953), will be examined in more detail in the next chapter on the Cold War.

New Nations and Development

The newly-founded countries in Africa and Asia all faced the challenges of establishing borders, forming new governments, building economic self-reliance, controlling natural resources, and working toward a more just and equitable society. In previous chapters, we have seen how the new nations in Latin America had confronted similar issues since the early nineteenth century. Other older but less-industrialized countries, like Iran, also addressed questions of development and national sovereignty.

One of the major challenges faced by these new nations was the problem of borders. The administrative boundaries drawn by the European imperial powers did not always follow any logic that served the colonized peoples; take Kashmir for example. An instance further complicated by the fact that both India and Pakistan were now nuclear powers (India since 1974 and Pakistan since 1999). India also supported the independence of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the early 1970s, a conflict which brought famine and death to hundreds of thousands in the same region that had been starved out thirty years before during World War II.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s division by the European powers had also haphazardly thrown together peoples who wanted separate nations. Violent conflicts based on tribal loyalties have caused civil wars and political instability. For instance, when the Igbo people tried to form a separate nation in Nigeria in 1965, the three-year civil war that followed killed thousands before Biafra was defeated. The disputed region is petroleum-rich (Nigeria leads Africa in oil production); so that even today, Igbo separatists harass the Nigerian government, resentful that their oil wealth seems to benefit the rest of the country more than it serves them.

Such conflicts do not only result in separatist civil wars though. No tribe advocates for their own independent state in Kenya, yet, conflicting tribal loyalties often spill over into political competition. Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta tended to favor his Kikuyu people, who were a plurality but not a majority in Kenya. At times causing widespread violence, as with the contested election in 2008 which led to the death of hundreds.

Nearly all of the new nations embraced democratic constitutions. However, it is one thing to write a constitution, and quite another to actually follow it. Like the older republics in Latin America, many new nations suffered through periods of authoritarian rule. Often, the military would step in and overthrow a democratically-elected government in times of perceived or actual economic or political chaos. The colonial powers had trained militaries as well as educating local administrators; army officers often felt that they were in a better position to rule their countries than incompetent and corrupt politicians, even if they had been elected democratically. The mistakes of the imperialists were often repeated in their former colonies. The Cold War complicated this situation, as fear of communist-led “wars of national liberation” frequently caused the United States and other Western “democracies” to support repressive military dictatorships.

Again, the example of India and Pakistan illustrates the problem of political stability in the new nations. India successfully embraced democracy and remains today the largest democracy by population. One reason for this was the popularity of the Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s. Another is the prominence of the Nehru family: after Indian Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru died of natural causes in 1964, he was succeeded by his daughter Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi) for twenty years, and she was followed by her son Rajiv Gandhi. Their dedication to democratic traditions brought a degree of political stability, although India was not free of problems that beset other new nations. Sikhs advocating for more power in Hindu India murdered Indira Gandhi in 1984 and ethnic Tamil separatists assassinated her son Rajiv in 1991. Despite these shocks, elections continued, and even opposition parties have taken the reins of government peacefully from the Congress Party since the 1990s; including current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected in 2014.

On the other hand, Pakistan has been ruled by their military more often than not since independence. Unlike in Nehru’s India, Pakistan did not benefit from an initial long premiership by its founding father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who died barely a year after independence of tuberculosis and lung cancer. Internal and international crises led to repeated interventions by the Pakistani military into national government. The 2013 Pakistani elections were the first time one democratically elected government peacefully replaced another. Yet, even today the military plays an independent, often secretive role in Pakistan, especially in foreign policy.

All of the new nations were faced with the question of how to develop their economies. Some governments were inspired by the apparent rapid industrial growth in the Soviet Union under Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, while others embraced the role of providing natural resources to the mature industrial economies of the West. Independent economic self-reliance was often difficult to achieve when industries and public utilities remained foreign-owned. Some new governments nationalized these businesses, so that the nation owned and operated them in the name of the people rather than for the profits of foreign shareholders. In India, for example, Nehru’s government nationalized the railroads, electric utilities, and communication systems. Seeing the results of India’s actions, many new African and Asian countries did the same.

Critics of nationalized industries argued that like the collectivized agriculture and industry of the Soviet Union, these businesses faced no competition. Their objections were taken seriously, partly because Stalin’s lies about the success of the Five Year Plans were finally discovered, and partly because nationalized industries often became inefficient as positions in a railroad or a telephone company transformed into political plums: no-show jobs awarded to loyal supporters. The foreign businesses that had been pushed out supported this view, and a reaction to nationalization, privatization, began in the 1980s. In India the push for privatization was led by Rajiv Gandhi, the grandson of the leader who had led nationalization efforts. In privatization, government-run industries were sold back to the private sector, which on occasion included, once again, foreign investors. Newly-privatized industries often initially embraced cost-cutting efficiencies and more competent management, repairing broken-down electrical grids and rail lines. However, as profits were once again exported abroad or held by a tiny local elite, there has been a push back against privatization, as some leaders once again seek more benefits for the entire nation.

In recent decades, a leader in the political push for privatization has been the International Monetary Fund (IMF), first established at the July 1944 conference at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Even before the war ended, forty-four allied nations sent 730 delegates to establish what would become a global system for regulating international balances of commercial payments and securing what they hoped would be financial stability for the post-war world. Initially, they were mainly thinking of creating institutions and policies that would both rebuild war-torn Europe and Asia and prevent the hyperinflation and Great Depression that led to so much instability between the wars.

There were two architects of the meeting and the global financial plan that came from it. John Maynard Keynes was the British economist who had pioneered the “demand-side” economic theory that people like U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had adopted to confront the Great Depression. Keynes’ claim was that by spending money, the federal government could jump-start the economy, create jobs, and put the money in people’s pockets that would enable them to buy consumer products. This plan was temporarily derailed by war production and rationing, so it is unclear to many economists that Keynes was right and that deficit spending and government borrowing was the key to ending the Depression. At the time of the Bretton Woods Conference, Keynes was the chief advisor to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Britain. The American, Harry Dexter White, worked closely with Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. and dominated the conference. Although he considered himself a Keynesian, White vetoed Keynes’s proposal for the International Clearing Union (ICU), a central bank with its own currency, the “bancor”. White opposed the ICU and instead proposed an International Stabilization Fund that would help debtor nations maintain their balance of trade. This grew into the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IRBD), which became the World Bank. The U.S.’s goal was to promote international development but also to help establish markets for American manufactures, now that the war effort had greatly increased U.S. manufacturing capacity.

Another reason the U.S. rejected the ICU and the “bancor” was to protect the leading position of the dollar in the world economy. Since the U.S. had the strongest economy in the world at the end of the World War II, they also dictated the trade provisions agreed to at the conference. The major provisions of the agreement were a foreign exchange system with the U.S. Dollar as its base currency, along with a pledge by members to convert their currency to gold for trade-related demands. Countries were required to adopt the gold standard and were not allowed to alter their currency’s exchange rate by more than 10%. This would prevent debtor nations from escaping their obligations to creditors by simply inflating their currencies. Finally, all members had to pitch in to the new bank’s assets, although the U.S. put up most of the money.

Bretton Woods also drafted a set of trade-related recommendations and an International Trade Organization (ITO) was proposed, with a goal of reducing tariffs. The United States Senate, however, was not interested in ceding its authority over tariffs to a new international organization, and did not ratify the ITO’s charter. The less aggressive General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was adopted in its place. We will discuss it when we cover Globalization.

Bretton Woods created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lends money to distressed economies suffering from hyperinflation or other financial chaos and, as a condition for credit, stipulates how a borrower country should reorganize government spending and finance. Which the U.S. undermined when it went off the gold standard in 1971. Nixon’s unilateral decision was ratified by Congress in 1978. By the end of the 1970s, no major currency was convertible for gold. Although the dollar is no longer redeemable in gold, the United States continues to maintain a gold reserve of over 8.1 metric tons , more than half of it stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky. The next largest national gold reserve, roughly 3.3 metric tons, belongs to Germany

Bretton Woods created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lends money to distressed economies suffering from hyperinflation or other financial chaos and, as a condition for credit, stipulates how a borrower country should reorganize government spending and finance. Which the U.S. undermined when it went off the gold standard in 1971. Nixon’s unilateral decision was ratified by Congress in 1978. By the end of the 1970s, no major currency was convertible for gold. Although the dollar is no longer redeemable in gold, the United States continues to maintain a gold reserve of over 8.1 metric tons , more than half of it stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky. The next largest national gold reserve, roughly 3.3 metric tons, belongs to Germany

Losing their original reasons for existence, the IMF and World Bank were forced to adapt. Rather than enforcing convertibility, the IMF began using its ability to loan interest-free development money to debtor nations as a way to intervene in and direct the economic policies of the borrowers. The IMF’s stated aim was to avoid or mitigate financial crises, using the “conditionality” of their loans. The IMF now analyses nations’ economic policies and offers “advice” which must be taken in order to receive IMF loans.

The changes the IMF and the World Bank require are called Structural Adjustment Programs. They typically include deregulation, privatization, and removal of trade barriers. All of these measures have been criticized by debtor nations as being more beneficial for the lenders in developed industrialized nations rather than for borrowers in the developing world. Other structural adjustments can include reducing trade deficits through currency devaluation, austerity programs to decrease budget deficits, eliminating social welfare programs, cutting public services, focusing economic output on resource extraction, and attracting foreign direct investment. This current bundle of structural adjustment programs is known as the Washington Consensus and is associated with neoliberalism or market fundamentalism, which we will discuss in a later chapter. Even in its more modest formulation, IMF policy is designed to liberalize trade, deregulate and privatize industries, and protect property rights above all other concerns.

The Green Revolution

Knowledge Check:

Now that we’ve witnessed those once colonized gain their “freedom”, let’s see how much we remember about their journeys…

- Questioning Imperialism

- Why did leaders like Churchill believe they would be able to return to controlling their empires?

- Why did colonized people disagree?

- Independence and Partition of British India

- In what ways were the British responsible for the antagonism between India and Pakistan since independence?

- Israel

- Is it surprising that Palestinians resent Israel’s existence?

- Do you think the major issue is anti-Semitism, when both Muslim and Christian Arabs have fought Israel?

- How might the extremely high level of financial and military Israel receives from the U.S. complicate Middle-eastern diplomacy for both the Israelis and the Americans?

- “British” Kenya

- Why might it be significant that revolutionaries like Kenyatta, Ho, and Gandhi were world travelers?

- “French” Algeria

- How might the scope of European retaliation, killing about ten Africans for every European killed, have effected world public opinion?

- “French” Indochina

- Is it significant that Ho Chi Minh worked with the OSS during World War II when he was opposing Japan?

- How many chances were there in Ho’s story, where history could have turned out differently?

- New Nations & Development

- How did Stalin’s lies about the success of the Five Year Plans affect the decisions of newly decolonized nations?

- In what ways did the problems of borders and religious differences continue to plague the new nations?

- What do you think the response of the communist U.S.S.R. may have been to the Bretton Woods Conference and the IMF?

- Is it possible to interpret the IMF’s role as global lender as a continuation of a new, economic form of imperialism?

- The Green Revolution

- What were the pros and cons of the Green Revolution?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- Winston_Churchill_waves_to_crowds_in_Whitehall_in_London_as_they_celebrate_VE_Day,_8_May_1945._H41849 © Major W. G. Horton is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Fighting_Filipinos_-_NARA_-_534127 © National Archives and Records Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jomo_Kenyatta_1966-06-15 © Government Press Office is licensed under a Public Domain license

- KAR_Mau_Mau © Ministry of Defence is licensed under a Public Domain license

- A_photographer_takes_pictures_of_starving_children_in_Biafra_Nigerian_civil_war © Peter Williams is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Indira_Gandhi,_Jawaharlal_Nehru,_Rajiv_Gandhi_and_Sanjay_Gandhi © Royroydeb is licensed under a Public Domain license

- WhiteandKeynes © International Monetary Fund is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-International_Monetary_Fund_logo.svg © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license