3 The Americas and Columbus

Chapter Outline:

This time around we’ll take a trip back to the ancient version of our own backyards! We’ll also work to debunk the notions that Modern World History and U.S. History started the day Cristoforo Colon “discovered” America. While first contact was absolutely a turning point, the whole story is a bit more complicated than we’ve been told. Strap in, because we’re going to dive into the “New World”!

- “Old World” meets “New World”

- The Columbian Exchange

- Europe

- Mestizos

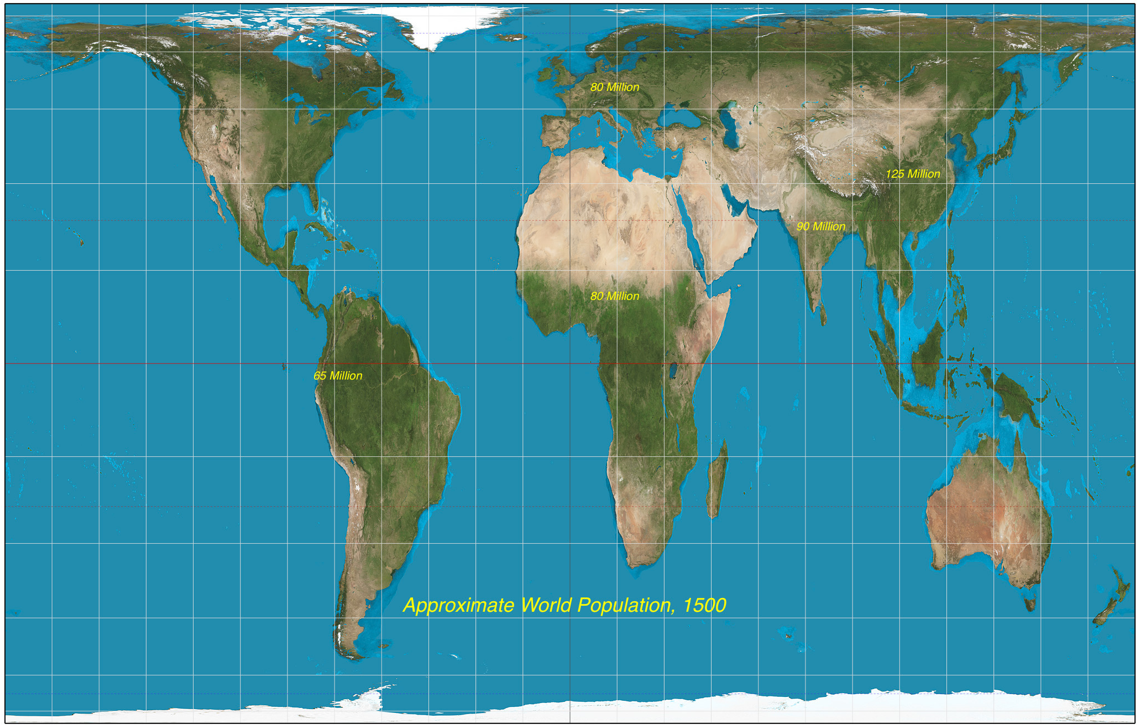

One of the most important things to note is that in 1500, the populations of Europe, Africa, and the Americas were quite similar. European and Asian populations had substantially recovered from the plagues and were rising; continental Asia dominating of course. (See map above for some numbers!) However, this demographic parity would change very quickly, as we will soon see…

“Old World” meets “New World”

As described in the Introduction, the people living in the Americas had been separated from Eurasia since the end of the Ice Age. During this period, Native Americans experienced their own agricultural revolution but did not domesticate cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, and chickens. Instead they developed certain plants, creating three of the world’s current top five staple crops: corn, potatoes, and cassava, as well as additional plants such as hot peppers, tomatoes, beans, cocoa, and tobacco.

Reliable, storable, staple food supplies are a necessary precondition for the creation of cities. Once they had created a reliable food supply, American natives built remarkable cities, especially in Central and South America. From present-day Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula south through Guatemala, the Maya developed a complex society which reached its most intense flourishing during their “Classic Period” (250 CE-900 CE). However, by the time the Spanish arrived, the Maya were living in more separated independent city-states, seemingly having abandoned some of their more impressive temples and structures such as Chichén Itzá in Yucatan. This led to an interpretation that the original society suffered a partial collapse sometime around 900 CE due to feuding among these separate cities.

The natives of North America also settled in complex societies in various regions, based mainly on the cultivation of corn, wild rice, squash, and pumpkins and on managing the environment to promote the success of game animals. The traditional U.S. and Canadian Thanksgiving dinner celebrates the native foods of North America, including the turkey. Along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, indigenous people lived mostly in villages but occasionally gathered into cities and built mounds like those found at Cahokia.

The Algonquian and Iroquois were semi-sedentary, living throughout what is now upstate New York and southern Quebec and Ontario. By the time of contact with Europeans, the Iroquois had formed a confederacy of five major tribes. The Ojibwe and Dakota were also semi-sedentary, living in settlements in the western Great Lakes region and on the edge of the northern Great Plains. By the time of contact with the Europeans, the Dakota dominated the Plains, where they took advantage of the large herds of buffalo as a source of protein, clothing, and housing, while gathering wild rice and cultivating corn and squash for carbohydrates. Many North American forest-dwellers also developed the sap of the maple tree as a key source of sugar. Of course, all this agriculture and city-building and civilization was happening in the Americas without anyone in Europe, Asia, or Africa knowing about it.

-

- It is NOT true that everybody believed the world was flat until Columbus came along, some Europeans were unclear on the actual size of the Earth, the existence of American continents and the Pacific Ocean.

- It’s also important to realize that European exploration did not BEGIN with Columbus.

The collapse of the Mongol Empire at the end of the 13th century and the plagues of the 14th century increased the perceived danger of overland travel. Columbus had failed to interest Portugal in his proposal to find a sea-route to Asia, because Bartolomeu Dias had already discovered a route to Asia around the bottom of Africa. On the other hand, Spain had recently unified with the marriage of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castille, and the monarchs had just completed the Reconquista and ejected Muslims from Granada, their last kingdom on the Iberian peninsula.

With all this settled, and after nearly 800 years of warring, Spain now turned theirs sights outward, yet, not away from the usual. Their war on behalf of religion and glory would continue in the New World. We must also note that the inventions that sparked this new era of exploration and empire building, like the sternpost rudder, the compass, gunpowder, and the printing press, were all Chinese inventions that found their way to Europe over existing international trade network and dominated by Arab merchants. This network would soon extend into the Americas!

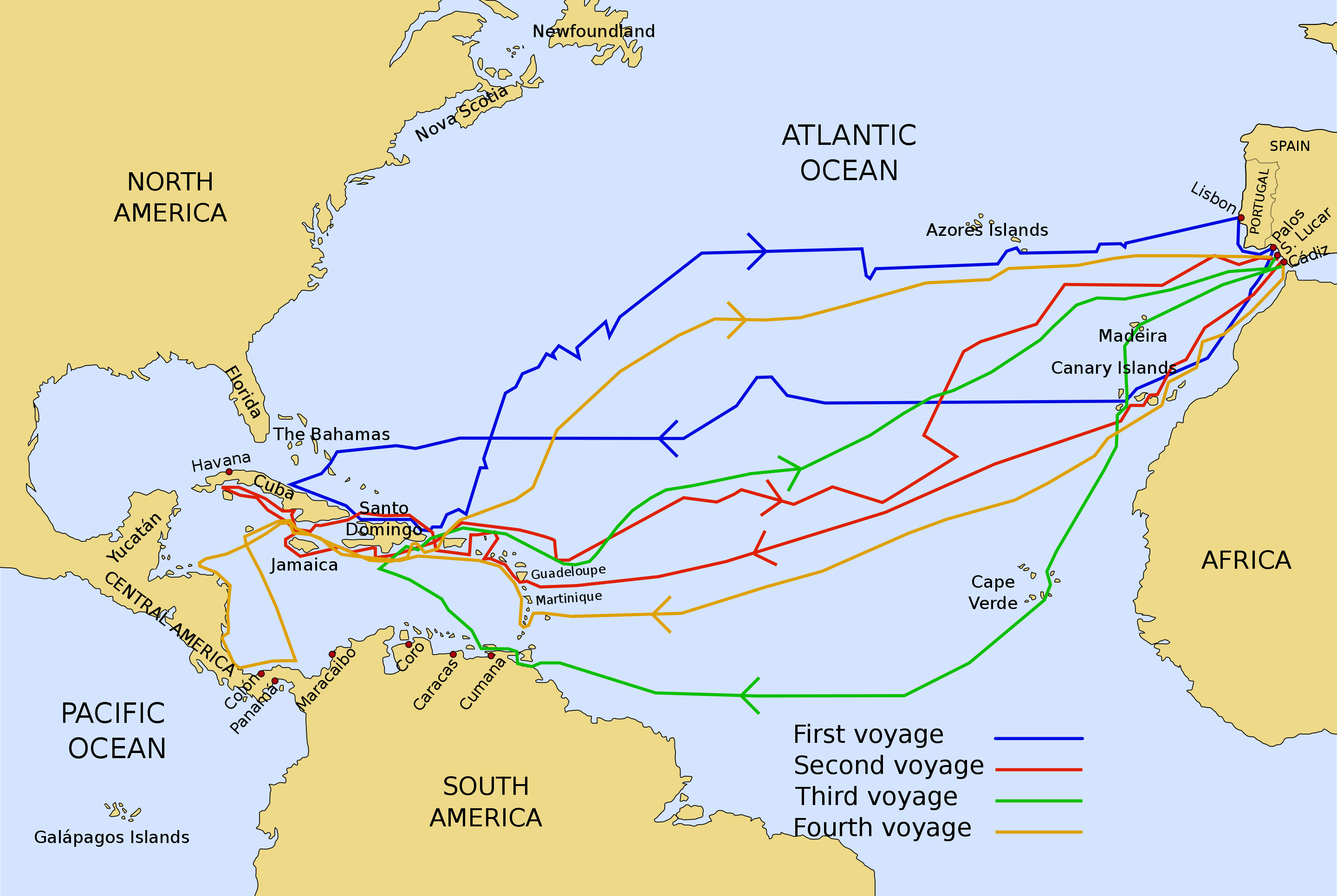

Columbus arrived in the Caribbean on October 12, 1492, and explored until late December. His flagship, the Santa Maria, ran aground on Hispaniola on December 25 and had to be abandoned. With permission of the local chief, Columbus left 39 sailors behind in a settlement he named La Navidad. He returned to Europe with two ships, a few captive Taino natives, some gold, and specimens of New World species including turkeys, pineapple, and tobacco. Arriving in Barcelona in mid-March, Columbus was celebrated as a hero.

It is often mentioned that Columbus believed he had reached Asia, and he did make that claim in his extravagant “Letter on the First Voyage.” Yet, this document was the explorer’s report to his royal sponsors, and Columbus wanted very badly to be sent back again. Whether or not Columbus understood he was reporting on lands previously unknown to Europeans, he definitely got his readers excited about the places he had visited.

When other European explorers reached America they were equally amazed. People throughout Europe read exciting traveler’s accounts like Amerigo Vespucci’s 1504 best-seller, Mundus Novus, which actually coined the term New World and made it clear for anyone who might still be confused, that these lands were not Asia but a previously unknown continent. Like Columbus, the explorers carried back to Europe not only eyewitness accounts of wealthy civilizations, but samples of native plants, animals, and captive people.

Columbus returned to the Caribbean in 1493 with 17 ships, 1,200 men, and according to his diaries, “seeds and cuttings for the planting of wheat, chickpeas, melons, onions, radishes, salad greens, grape vines, sugar cane, and fruit stones for the founding of orchards.” Other old-world crops that thrived in the Americas included coffee and bananas, originally cultivated in Africa and Asia, which were brought from the Canary Islands in 1516. The Spanish had introduced sugar cultivation to the Canary Islands in the early fifteenth century, and transplanted canes to the tropical paradise their explorers had discovered across the Atlantic.

Cattle were delivered to Spanish conquistadors in Mexico in 1521. Most of the significant Eurasian species brought to the Americas by European explorers and colonists were introduced by the Spanish by the early 1500s, long before North American settlement began. Even species like the wild horses of the American West that would transform Plains Indian culture in the 18th and 19th centuries were the descendants of escapees from the herds of the conquistadors. The Americas had very few large mammal species, and most could not be domesticated. Nearly all the species humans have successfully domesticated, the familiar residents of the modern farmyard, originated in Europe and Asia. These include goats, sheep, cows, horses, pigs and chickens.

The Spanish and Portuguese dominated the first century of exploration, conquest and colonization in the Americas for many reasons. Spain and Portugal had an eight-century long tradition of warfare from fighting the Reconquista against the Moors, and were prepared for further battle for glory and religion. The Portuguese also had a maritime tradition, which was how Columbus learned his trade. However, the two Catholic nations also had a papal charter. The Spanish and Portuguese were granted a license by the Pope under the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which awarded all the territory east of the 47th meridian to Portugal and everything west of it to Spain. The Pope (Alexander VI) who made this deal was a Spaniard named Rodrigo Borja – his reign was known for nepotism and corruption, and, despite a pledge of clerical celibacy, he was the father of the famous Italian political family known for poisoning their enemies, the Borgias. The Portuguese received the east, because they were already establishing colonies on the east and west coasts of Africa. The Spanish were assigned the unknown west, which turned out to be bigger than anyone had expected. The Pope granted nothing to any other European kingdom. This type of corruption at the Vatican helped motivate reformers like Martin Luther toward what became the Protestant Reformation.

The Columbian Exchange

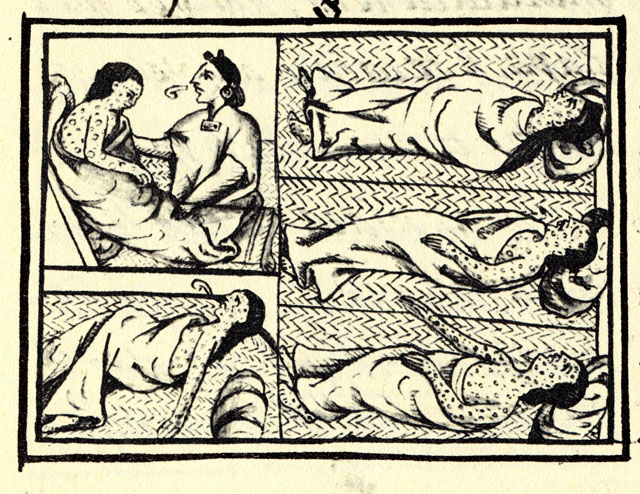

Most of humanity’s major diseases originated in animals and crossed from domesticated species to their human keepers. Whooping cough and influenza came from pigs; measles and smallpox from cattle; malaria and avian flu from chickens. Without the inherited protection enjoyed by most Eurasians and Africans, even a routine childhood disease such as chickenpox was initially devastating for Native Americans, who did not have domesticated animals and thus little acquired immunity to these diseases.

The introduction of a disease into an area without inherited immunity is called a virgin soil epidemic. Virgin soil epidemics spread across the Americas when explorers and colonists introduced Eurasian diseases to the Native Americans. The Eurasian diseases that attacked native populations included smallpox, measles, chickenpox, influenza, typhus, cholera, typhoid, diphtheria, bubonic plague, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and malaria.

The impact of these Eurasian diseases on Native Americans was one of human history’s most abrupt and severe population disasters. American native populations had no safeguards, and disease spread virulently. For example, there were over a million people living on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1492 when Columbus left his 39 sailors in La Navidad. By 1548, there were only 500 natives left alive. 999,500 people had disappeared in a little over 50 years.

The populations of other Caribbean islands like Cuba were similarly wiped out. Whole societies disappeared, and this was not only a tragedy for the cultures that vanished. The reduction of native populations began a cycle of violence that became central to the history of the Americas. Once there were no natives left to work on European sugar plantations, enslaved Africans were considered crucial to the survival of the West Indies sugar economy.

The greater population densities of Central and South America enabled contagious diseases to spread more quickly there. Heavily-traveled roads in central Mexico actually helped spread disease beyond areas that had been reached by Spanish explorers. Cities were wiped out that had never seen a white man. The population of the Aztec heartland dropped from about 25 million on the eve of the Spanish conquest in 1519 to just under 17 million a decade later. After another decade the Aztec population was reduced to about 6 million. By 1580, the Aztec empire had been hollowed out to less than 2 million people, from a starting point of 25 million.

Traditional European or Eurocentric American histories of exploration often present the victory of the Spanish over the Aztec as an example of the superiority of Europeans over the savage Indians. The reality is far more complex! In addition to using the Aztec’s enemies against them Cortés was also aided by an enslaved Nahua woman, Malintzin (also known as La Malinche or Doña Marina, her Spanish name), whom the natives of Tabasco gave him as a tribute slave. In addition to speaking Nahua and Maya, Malintzin quickly learned Spanish and translated for Cortés in his dealings with Aztec emperor Moctezuma.

Willingly or under pressure, Malintzin, entered into a physical relationship with Cortés. Their son, Martín, was one of the first “mestizos” in Spanish America. Malintzin remains a controversial figure, seen as a traitor because she helped Cortés conquer the Aztecs and as a victim of European imperialism whose choices were very limited. In either case, she demonstrates one way in which native peoples responded to the arrival of the Spanish. Without her, Cortés would not have been able to communicate, and without the language bridge, he surely would have been less successful in destabilizing the Aztec Empire. By this and other means, native people helped shape the conquest of the Americas.

The Inca Empire in the Andes suffered the same fate. 90% of the South Americans died, and they started dying BEFORE the white invaders arrived in 1532, which caused confusion and dismay. When Pizarro crossed the Andes with eighty conquistadors, he found social chaos. Huayna Capac, the Inca leader who had triumphantly extended the empire into Chile and Ecuador, had died of smallpox in 1527. His two sons fought a brutal civil war for control of the empire, the younger son Atahualpa finally defeating and assassinating his older brother Huáscar. The civil war exacerbated the effects of epidemics, and the weakness of the reduced Inca population gave Pizarro the opportunity he needed to capture and kill Atahualpa in 1533, beginning the end of the Inca empire.

Although the conquistadors focused much of their energy on Central and South America, they brought disease to North America as well. After helping Pizarro conquer the Inca, Hernando De Soto landed an expedition in Florida in 1539 and explored territory now in the states of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Oklahoma. Everywhere he went, the conquistador reported the land was “thickly settled with large towns.”

De Soto didn’t stay long. He died of fever in Louisiana in 1542, and although the region was visited by a few missionaries, it was not seriously considered again by Europeans until the French aristocrat, La Salle, traveled down the Mississippi River in 1670. Where De Soto had seen fortified towns, La Salle saw none. The entire region had been emptied by the diseases which accompanied De Soto and his men, and had returned to wilderness. The French explorer reported traveling hundreds of miles without passing a single village. Historians were actually unaware until recently that the American South had once been heavily populated before the arrival of contagious Spanish explorers and missionaries.

Spanish invaders had not deliberately infected the natives with all these diseases (Europeans still had no idea at this time how viruses or bacteria worked), but they were quick to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the social chaos and military weakness of native societies in crisis. In both Mexico and Peru, the conquistadors found allies among different indigenous groups who often thought of themselves as the victors, with Spanish help, rather than the other way around. Still, within a few years, the Spaniards took over the capital cities of the Inca and Aztec empires, inserting themselves into the top positions in the pre-existing governments. Patterns of tribute were maintained, as well as the labor draft of the Inca mita; although now labor would be devoted to the silver mines and not just road, irrigation, and building projects.

As they had been in Spain during the Reconquista, conquistadors were rewarded for military service with encomiendas. From a root word meaning “entrusting,” encomiendas were grants of captured territory and the people that lived on it, who the encomendero was theoretically responsible for bringing into the Christian community. This technique had been used in Spain to keep track of conquered Muslims and make sure they did not backslide after their forced conversions. In Spanish America, there was a much greater emphasis on taxing and working the new peasants, rather than leading them to religion.

Europe

As previously mentioned, American staple crops were successfully adopted by farmers in Europe, providing better and more reliable nutrition which sparked a population boom. New foods like potatoes were so important in preventing the cyclical famines that regularly hit Europe, that they became a key topic in Adam Smith’s classic, On the Wealth of Nations. Many plant species developed by native Americans are still crucial to the world economy, including not only maize, potatoes, and cassava, but also tomatoes, sweet potatoes, cacao, chili peppers, natural rubber, tobacco, and vanilla. Quinine, a medicine made from the bark of the Peruvian cinchona tree, was effective treating malaria and helped open the African and Asian tropics to European colonization. Eurasian plants like sugar, soybeans, oranges, bananas, and rice (which probably reached America from Africa along with enslaved women who were experts growing it) were also extensively cultivated in the Americas for profitable shipment back to European markets. Exports of native and transplanted crops helped feed growing cities and, by the mid-18th century, freed agricultural workers to enter Europe’s new industries. Without inexpensive and abundant Native American foods, there might have been no Industrial Revolution.

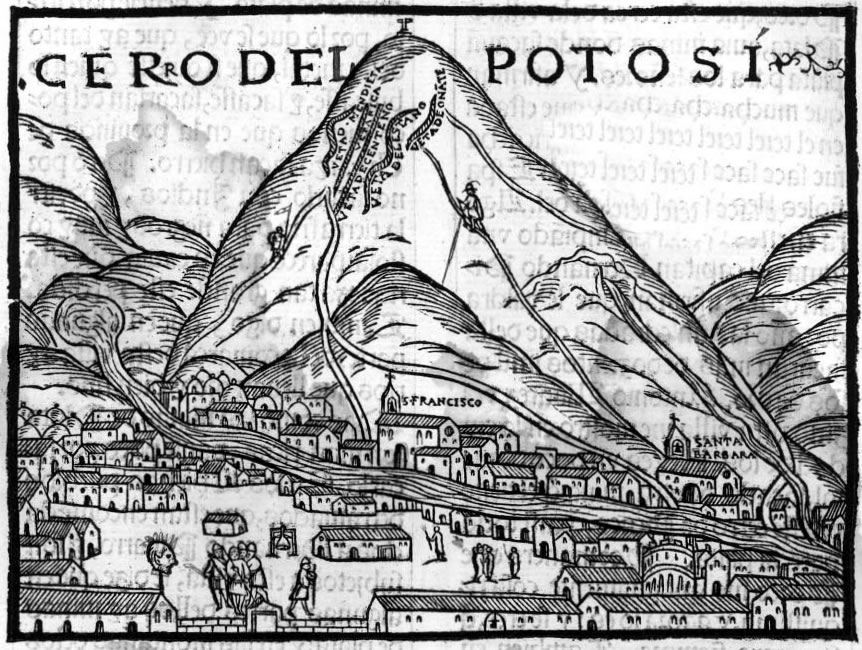

Like the Portuguese in their exploration of Africa, the Spanish were also interested in finding sources of gold and silver for the European commerce. Although they never found El Dorado, Europeans did find a fair amount of gold and they found even more silver.

For example, the Bolivian city of Potosí, located in the Andes at an elevation of 13,420 feet (over 4,000 meters), still has the largest population of any city at that altitude. Established by the Spanish in 1542, it is the site of a long-standing native mining village at the foot of the Cerro Rico, which is a literal mountain of silver.

Every year between 1566 and 1815, a treasure fleet sailed from Acapulco to Manila laden with silver for the trade in China and India. Another fleet carried not only precious metals but spices and expensive Chinese ceramics acquired in Asia from Veracruz to Spain.

Once again, products originating in the Americas were a spur to the Industrial Revolution. Without the money minted from Latin America’s silver and gold, there might have been no global commercial boom to finance European industrialization. And Potosí’s story is not over yet. Although most of the easily-extractible silver was taken out of the mountain centuries ago, the Cerro Rico is still being worked by Bolivian children whose story is told in the award-winning documentary, The Devil’s Miner, which you can view on the web if you’re interested in learning more.

Mestizos

As the majority of the Spanish in the New World were male soldiers in the first decades of the conquest, women were taken, often forcibly, from native communities to be wives and mistresses. One high-ranking Inca native named Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala wrote to the King of Spain around 1600, complaining that Spaniards are taking all the Indian women of childbearing age, so the place was being flooded with mestizos who were not required to work as the Indians were. Worse, the fathers were not supporting their illegitimate children, and “if a Spaniard steals away four Indian women to make little mestizos, he will bribe the judges and refuse to recognize his paternity,” leaving their support up to the state. “Spaniards ought to live like Christians,” Guaman argued, “marrying ladies of equal status and leaving the poor Indian women alone so they can have Indian children.”

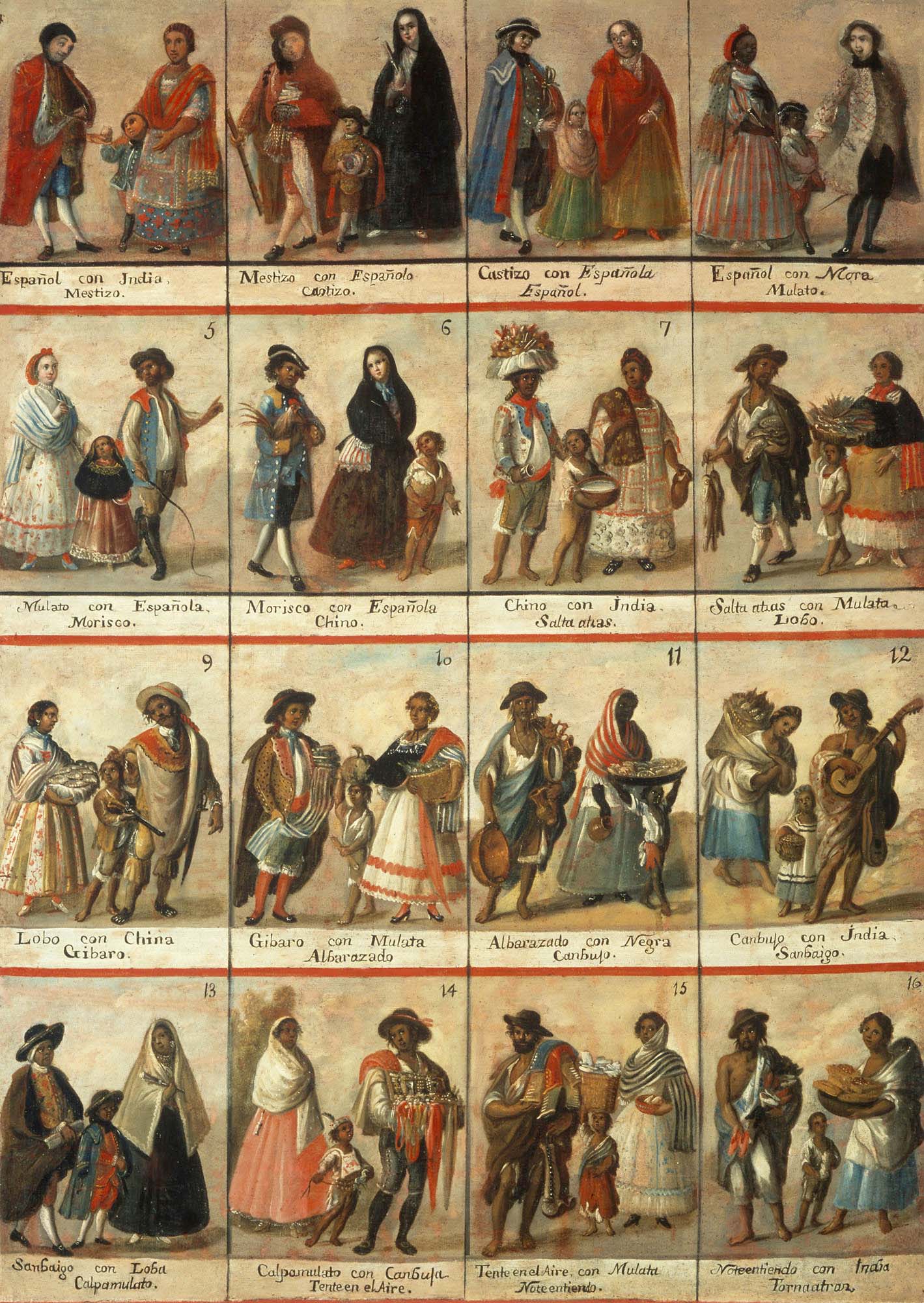

Most of the countries of Latin America are built on mixed or mestizo populations; so much so that in the 1700s, the colonists tried to make distinctions between all the various types of people they believed made up their societies, to “prove” to the Spanish Crown that a logical caste system existed in the colonies. Although these distinctions were somewhat arbitrary and were often used to uphold the power of the group at the top, in the long run many of these mixed Euro-American populations have developed strong ethnic identities. A similar process happened in New France–today’s Quebec in Canada. There were only about twenty-five hundred French people in the province by 1663. Most of them were voyageurs, fur traders who went into the northern forests to make their fortunes. Voyageurs frequently married local Indian women, and their Canadian descendants are now recognized as a distinct ethno-cultural group called Métis.

The social caste system developed in Latin America was based on both blood and origin. Meaning…

The Portuguese were initially more interested in dominating trade routes in the Indian Ocean, so they mostly ignored their new possession in Brazil until French Huguenots, protestant Christians fleeing Catholic France, tried to establish a colony near present-day Rio de Janeiro in the mid-1500s. By that time, the Portuguese had watched the Spanish become successful cultivating sugar cane in the Caribbean. Thus, Portuguese entrepreneurs decided to bring cane and slaves to Brazil and set up plantations along the northern coast. By this time, the Catholic Church had prohibited the enslavement of Indians, but not of Africans. Native Brazilians did not establish the complex societies found in Mexico, Central America, and Andean South America, so it was actually harder to “conquer” them, as they escaped deeper into the interior jungles and forests. However, the Portuguese already had established colonies and trade ties in Africa, which soon supplied enslaved labor to the sugar plantations.

As described in the previous chapter, slavery was a traditional element in all world societies, including those of Africa, but Europeans quickly grasped the usefulness of having enslaved Africans in European communities because it would be harder for them to blend in with the local population. The sugar trade spurred the slave trade, as well as European notions of racial superiority to justify the enslavement of people with darker skins.

By the mid-1500s in Europe, Spanish wealth began to cause problems. Wealthy Spanish nobles married into aristocratic families like the Austrian Hapsburgs. In 1519 (the same year Cortés attacked Tenochtitlán and Magellan set out to circle the Earth) the grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles V, became Holy Roman Emperor. Charles was also King of Spain and (by marriage) Portugal, which gave him legal control of all the American colonies. When his wife Isabella died in 1555, Charles was inconsolable. He abdicated in 1556 and retired to a monastery, leaving his younger brother Ferdinand in charge of the Holy Roman Empire in Europe and his son Philip II in control of Spain, Portugal, and their possessions (including the “Spanish Netherlands” on the European coast).

Although Philip II was called “The Prudent,” and was also briefly King of England while married to Queen (Bloody) Mary, after she died in 1558, he lost control of the rebellious Protestant Dutch Republic and Spain declared bankruptcy five times. Spain’s financial troubles were partly due to debts Philip’s father Charles V had accumulated as Holy Roman Emperor. After Queen Mary’s death, Philip proposed to her successor, Elizabeth I, who turned him down. Elizabeth’s father, King Henry VIII, had separated the Church of England from Rome in the 1530s, after a dispute with the Pope over the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella and aunt to Charles V. Philip supported the claim of Mary Queen of Scots to the British throne, but when she was executed in 1587, Philip decided to invade and return England to Catholicism.

In 1588, the Spanish Armada organized by Philip was hampered by bad weather on the English Channel and then defeated by the British Royal Navy, which lost no ships while Spain lost five before withdrawing. During the retreat, most of the Spanish navy was destroyed by storms, leaving the British and the Dutch in control of the Atlantic. Later that year an English fleet sailed into the harbor at Cadiz, burned 200 Spanish ships and made off with the annual silver shipment. It was the beginning of the end of the Spanish Empire as a major European power.

Another reason Spain did not permanently dominate the European economy was that for centuries most of the silver they shipped from Peru and Mexico ended up in China, where silver was the basis of the earth’s largest economy. Buoyed by China’s economic dominance, the Asian population increased from 60% of the world’s people to 67% between 1500 and 1800. In addition to the Mings in China, the Mughals in India ruled an empire of 150 million people, and they were very interested in expanding trade with the West. India was also highly productive; between the two empires, Asia produced 80% of all the world’s goods. Even though we are concentrating in this chapter on the intricacies of the Atlantic World and the intersection of Africa, Europe, and the Americas, until the mid-1700s, it is important to remember that China and India dominated world commerce and industry.

Chinese silks and Indian cotton were the world’s best quality and lowest-cost textiles, and clothes made from them were worn throughout the world – even in Spain’s colonies where the law required people to trade only with the home country. The national costume of Mexico is called the China Poblana; it was originally a contraband silk dress worn by women of the towns. The British were so intimidated by Asian textiles that they imposed tariffs to try to protect their own weavers from being driven out of the business. Mercantilism, in which colonies served the home country as both a market and a source of raw materials in a closed economy, was actually not a primitive economic system that evolved into free market capitalism. It was an attempt to shield British and European merchants from an already-existing international free market in which they were too often the losers to the dominant Asian powers.

Knowledge Check:

This time around we’ve taken a trip back to the ancient version of our own backyards! We worked to debunk the notions that Modern World History and U.S. History started the day Cristoforo Colon “discovered” America. While also dissecting the turning point that the “Old World” meeting the “New World” was…

- “Old World” meets “New World”

- Why do you think stories of Columbus remain controversial?

- Why is it important that Europe, Africa, and the Americas had populations of similar size just before contact?

- Is it significant that several pre-Columbian cultures were not at their peaks when the Europeans arrived?

- How does the existence of a written language alter how we think of people’s level of civilization?

- Why are native agricultural systems so impressive?

- Why did historians tend to disbelieve stories of Viking settlement in Vinland until recently?

- Why were Europeans so interested in sailing across the Atlantic to fish for cod?

- Why were the Spanish monarchs interested in financing Columbus’ voyage but the Portuguese not?

- What caused Europeans to get so excited about the newly-discovered lands?

- Why did the Spanish and Portuguese dominate early colonization?

- The Columbian Exchange

- Why were native populations so susceptible to European diseases?

- How did disease affect native societies’ ability to resist European invaders?

- Was Malintzin a heroine or a villain in her collaboration with Cortés?

- How were regions far from the main points of European contact affected? What do you imagine it was like for natives?

- What tools did the colonizers use to organize native labor?

- Europe

- What were the main economic effects of Spanish colonialism in Europe?

- Mestizos

- Why were the Spanish so interested in “pure blood” and the various degrees of ethnicity in their colonies?

- What were the four major caste status levels in colonial society?

- How did dynastic politics in Europe affect the American colonies?

- Why was Asia so important to colonial America?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- Picture2 © Dan Allosso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 1962_Cuba_Missiles_(30848755396) © CIA is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Viajes_de_colon_en.svg © Phirosiberia is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- CantinoPlanisphere © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FlorentineCodex_BK12_F54_smallpox © Bernardino de Sahagún is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tenochtitlan_y_Golfo_de_Mexico_1524 © Fridericum Peypus is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tory_Refugees_by_Howard_Pyle © Howard Pyle is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-Inca_roads-en.svg © Manco Capac is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Capitulo-CIX © A.Skromnitsky is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Potosi_Mining_Photo_by_Sascha_Grabow © Sascha Grabow is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Casta_painting_all © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Yellow Modern Pride Month (Flyer) (1)

- Poblanas © Carl Nebel is licensed under a Public Domain license