1 The Modern World Begins in Asia

Chapter Outline:

We start our journey back in time with Asia. The histories of China and India are as old as western history, if not older, despite the impression that the important events of modern history took place in the West. Asia has always been the center of world population. So, let’s now look at how Asia achieved that global preeminence.

-

Civilization’s Rise in Asia

-

Tempered Steel: A Conquered China

- The Mongols!

-

The New Emperor

-

Zheng He

-

-

The Start of Isolationism

Civilization’s Rise in Asia

As mentioned in the Introduction, civilization began in India about 4,600 years ago and China’s recorded history began about 2000 BCE. Based on irrigated rice agriculture, the population of China grew to 50-60 million people as early as 2,000 years ago. This population was originally divided into several small kingdoms whose ruling families were connected through political marriages. Beginning in 221 BCE, the Chinese created an empire that lasted over two thousand years under a series of more than a dozen dynasties. The early imperial governments began construction of the called Long Walls, and dug the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in the sixth century CE. China held a monopoly on the creation of silk, which was a closely-held state secret for millennia, and led the world in iron, copper, and porcelain production as well as a variety of technological inventions including the compass, gunpowder, paper-making, mechanical clocks, and moveable type printing.

The social stability that allowed Chinese culture to produce these innovations was based on not only the imperial form of government, but on an elaborate system of professional civil service. The early establishment of a professional administrative class of “scholar-officials” was a remarkable element of imperial Chinese rule that made it more stable, longer-lasting, and at least potentially less oppressive than empires in other parts of the world. The imperial courts sent thousands of highly-educated administrators throughout the empire and China was ruled not by hereditary nobles or even elected representatives, but by a class of men who had received rigorous training and had passed very stringent examinations to prove themselves qualified to lead.

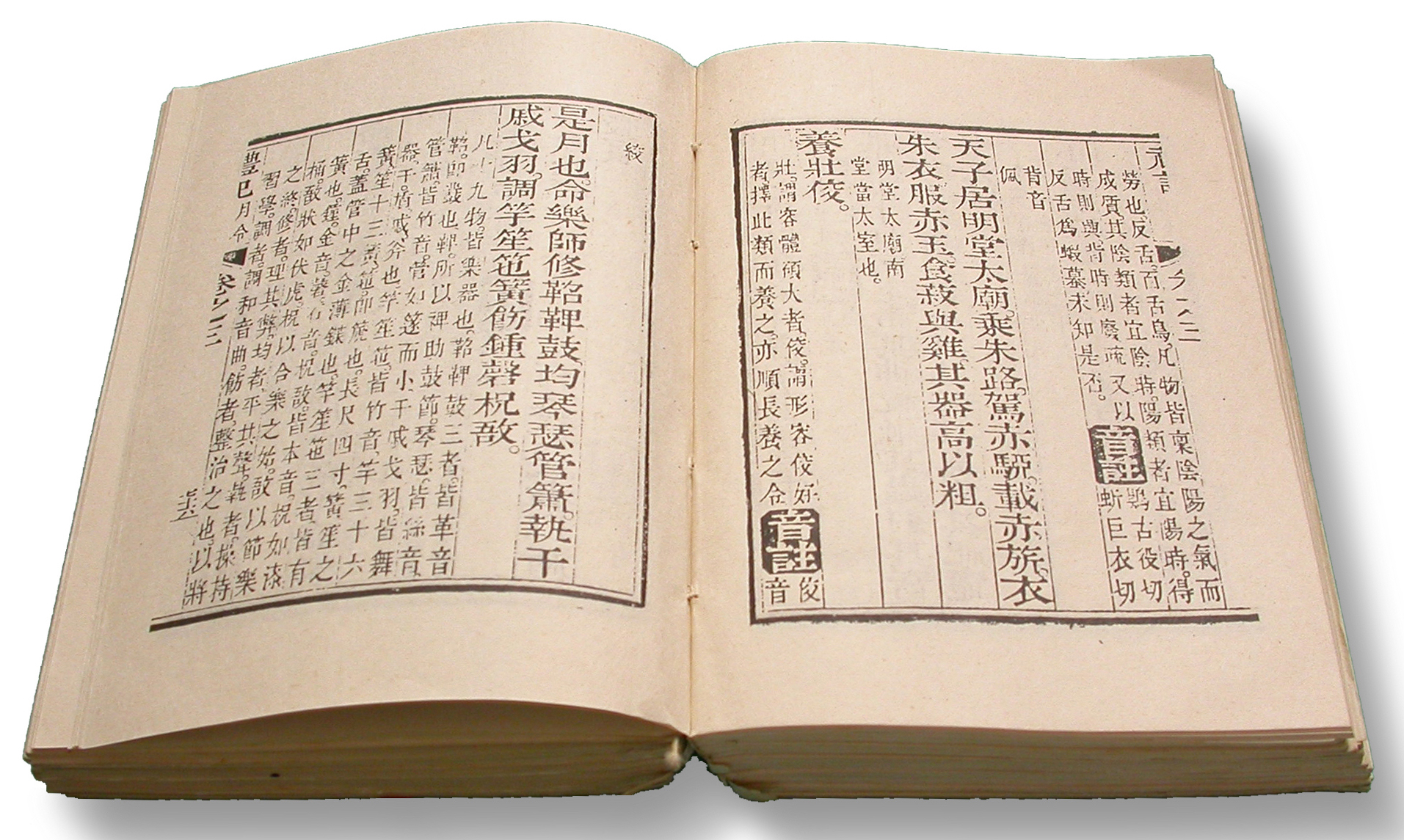

Young men who wanted to become civil administrators in China entered training schools that concentrated on calligraphy and the teachings of Confucius. Calligraphy in China equaled literacy. Chinese language is based on characters rather than on an alphabet, and is said to be the world’s oldest continually-used writing system. A dictionary published in 1039 CE listed 53,525 characters, and a 2004 Chinese dictionary included 106,230. Most Chinese words are made of one or more characters. For comparison, the English alphabet uses 26 letters and the average American has a practical vocabulary of about 10,000 words.

In addition to literacy, civil service training focused on the philosophy of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher who had lived from 551 to 479 BCE. Kong Fuzi (Master Kong—he is known as “Confucius” in the West) taught principles derived from what he described as old Chinese classics. Confucius claimed he was not so much creating a new philosophy as preserving and combining the best traditions of the past, which was very appropriate in a culture devoted to reverence of its ancestors. He traveled as a teacher and advisor of local rulers, and his practical philosophy spread. Confucian ideas about conduct focus on five basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness.

When a student asked him “Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?” Confucius replied, “How about ‘reciprocity’! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself;” also known as the silver rule. (Analects XV.24) Although Confucius occasionally talked about heaven and an afterlife, his moral system was not based on the idea of supernatural rewards and punishments. Secular Confucian morality allowed the Emperor to represent Divinity and claim “the Mandate of Heaven” without the Chinese Empire becoming a theocracy.

Centuries after his death, Confucian ideas became the basis of civil service education in imperial China. Scholars would travel to testing centers and sit for exams that often took days to complete. They brought food and a bedroll and remained in their small testing cells until they had completed the exam. There were four increasingly-difficult levels of testing: County, District, Province, and Imperial. The highest exam was administered by the emperor himself and passing it qualified a scholar for assignments in the imperial court. The exams were extremely difficult and more failed than passed; yet, the exams were also democratic in a way. Regardless of social or economic standing, anyone could take the exam! Over time these exams created a gentry, as in Europe, yet, based on educational merit rather than merely on birth or wealth; although corruption still existed.

Confucianism incorporated traditional Chinese ancestor-worship into its system, which implied a degree of sacredness for ancestral practices. For this reason, Confucian principles perpetuated and exacerbated the oppression of women, who had no standing in the male-dominated family structure.

-

- Considered an expense to their birth families, their sole purpose and value came with marriage and the birthing of sons.

- Female infanticide became the norm for families.

- And until the last century, the practice of foot-binding, which rendered generations of Chinese women crippled and semi-mobile for fashions sake.

Faults aside, Confucian civil service insured that for much of its history the Chinese empire, its various districts and regions, and even small communities were run by educated administrators and magistrates rather than by random rulers who achieved power by conquest or inheritance.

The Mongols!

Tempered Steel: A Conquered China

The Chinese Empire did face conquest several times, but Chinese culture and social organization managed to absorb its conquerors. In 1271, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, defeated the Chinese army and established the Yuan dynasty, which lasted 98 years. Although Kublai Khan never completely conquered China (he tried for 65 years), Yuan rule marked the first time the Chinese Empire was controlled by foreigners.

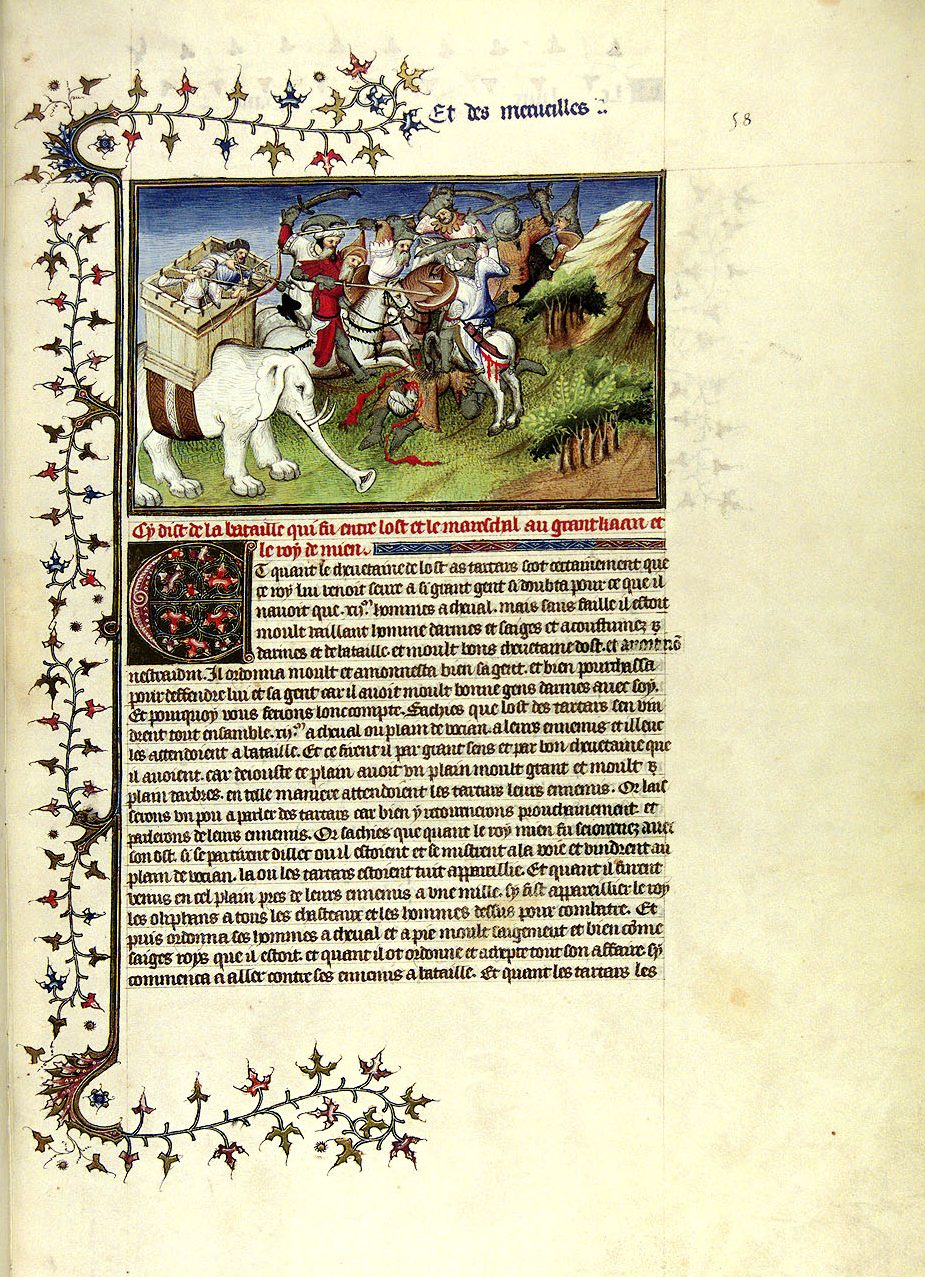

The Khan distrusted Confucian officials, but he did not completely replace them as regional administrators. Still, through the Yuan dynasty, China was exposed to foreign cultures, especially Islamic cartography, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, food, and clothing, while likewise, the West encountered Chinese culture and technological advances in a serious way. The Silk Road became a major highway of cultural exchange once more and the Mongol rulers also patronized China’s new printing industry, which helped spread the idea of moveable type printing into Europe.

Despite the fact that China’s Mongol Yuan rulers abandoned many of their own traditions and adopted the ways of the people they had conquered, the ethnic Han Chinese majority continued to resent being ruled by foreigners. Along with exposure to foreign cultures, the Mongols’ reopening of the Silk Road brought foreign diseases to China. The Bubonic Plague or “Black Death” hit China before Europe in the 14th century. China would loose nearly 25 million people in the 1330s and 1340s; about 15 years before it first arrived in Constantinople. As in Europe, famine and social chaos followed the plague when agriculture failed to produce enough to feed the survivors.

How did the Yuan rule come to an end?

- Short Answer: Zhu Yuanzhang

- Long Answer: Zhu lost his entire family to the post plague famines. He would then seek refuge in a monastery, which was destroyed by Yuan forces looking to stop an insurrection. While that insurrection was put down, an enraged Zhu became part of the resistance and, through marriage, soon found himself the leader of the rebel forces. At 28 years old, in 1356, he led the rebels into capturing Nanjing. From here, in 1368, he’d launch his forces at the Yuan and send them back into Mongolia. Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and so began the Ming Dynasty.

The New Emperor

Zhu Yuanzhang called himself the Hongwu Emperor (expansive and martial) and made Nanjing his capital. Imperial titles like “Hongwu” relate to the reign of each emperor, in which they declare the nature of their particular rule. These titles are not the actual name of the emperor, but this is how they are known in Chinese history.

Hongwu ruled for thirty years and tried to return the empire to its ethnic Chinese roots.

-

- Hongwu issued decrees abolishing Mongol dress and requiring people to abandon their Mongol-influenced names in favor of traditional Han Chinese names.

- Administration of the empire by Confucian scholars was reinstated, along with the elaborate system of civil service examinations.

Remembering the suffering and famines during his youth, partly caused by the flooding of the Yangtze River, Hongwu promoted public works and infrastructure projects including new dikes and irrigation systems to serve an agricultural system dominated by paddy rice. He organized the building or repair of nearly 41,000 reservoirs and planted over a billion trees in his land reclamation program. Hongwu distributed land to peasants and forced many to move to less populated areas. During his three-decade reign, China’s population recovered from plague and famine, and grew from 60 to 100 million.

Hongwu had fought his way to prominence by eliminating his rivals and trusting only his family. But when his first son, the crown prince, died, Hongwu left his throne to the son of his favorite son, rather than picking one of his other sons.. Hongwu’s grandson became emperor at 20, but his reign was a short one.

His uncle Zhu Di, the emperor’s younger son, had been passed over for the crown but remained prince of a northern territory around Dadu, the previous Yuan capital close to the Mongol border. In 1402 Zhu Di overthrew his nephew and declared himself the Yongle (perpetual happiness) Emperor.

Yongle tried to erase the memory of his rebellion by killing many scholars and moving the capital to his home town in Dadu; later renamed Beijing. Yongle ruled through an extensive network of court eunuchs who formed his palace guard and secret police. Yongle repaired and reopened China’s Grand Canal, and enabled the receipt of rice shipments from the south into the north. Between 1406 and 1420, he also directed 100,000 artisans and 1 million laborers in building the Forbidden City in Beijing as a permanent imperial residence.

The Start of Isolationism

The Long Walls had existed since the beginning of the Chinese Empire and had failed to hold off Mongol invaders, so another order of business was to secure the empire! Under the Ming’s the Great Wall was improved and extended, especially around the capital of Beijing and the agricultural heartland in the Liaodong Province north of the Korean Peninsula. These defenses enabled a population rise from 100 million in 1500 to 160 million in 1600. However, the threat of a Manchurian land invasion from the north was taken very seriously, to the detriment of authorizing further naval expeditions. China’s turning away from the ocean was a momentous decision in world history, opening the door for Southeast Asians, Muslims, and eventually Europeans to dominate the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

As the generations passed, Ming emperors and their courts became increasingly isolated in the Forbidden City the Yongle Emperor had built. Some were incompetent rulers, others were just uninterested in ruling. As time passed, a ruling class grew and power shifted as the new elite protected their lands and possessions from taxation. Corrupt officials siphoned funds designated for public works into their own pockets and infrastructure such as dams and dikes crumbled. Eventually, irrigation systems failed and peasants died in widespread famines again.

At the same time, Manchuria was being unified under strong military leaders who had adopted Chinese ways and who even employed Confucian administrators. In 1644, a Ming government official dealing with a local peasant insurrection that threatened Beijing asked the Manchurians for military aid. Of course, once the Manchu armies were past the Wall, there was no way to send them back. They took control of Beijing and declared the end of the Ming Empire and the beginning of a new dynasty, the Qing (pure).

We will return later to the history of China, the Qing Dynasty, and what came after. For now, the point of beginning modern world history with China is that in terms of population and economic power, it was the center of the world in 1500. The Chinese population was growing rapidly, the Ming Empire had a standing army of over a million soldiers and the Chinese navy of Zheng He had recently projected the empire’s power throughout Asia. The Chinese economy produced one quarter of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 1500, followed by India which produced nearly another quarter. In comparison, the fourteen nations of western Europe produced just about half of China’s GDP and the largest European economy, in Italy, produced only about one-sixth of China’s output.

The Ming Empire’s population in 1500 was about 125 million. The next largest empires were:

-

- Southern India’s Vijayanagara Empire (16 million)

- the Inca Empire of South America (12 million)

- the Ottoman Empire (11 million)

- the Spanish Empire (about 8.5 million)

- the Ashikaga Shogunate of Japan (8 million)

Keeping the immense mass of China and the gravity exerted by its economy in mind as we move on to discuss events like the creation of a Spanish colonial empire in the Americas. Spanish-American mines produced the silver that accidentally became the world’s currency, filled not only the treasuries in Europe, but also that of China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Yet, that’s a story for another day…

Knowledge Check:

The Modern World’s History Begins in Asia

We’ve started our journey back in time with Asia. The histories of China and India are as old as western history, if not older, despite the impression that the important events of modern history took place in the West. Asia has always been the center of world population. So, let’s now look at how Asia achieved that global preeminence.

- Civilizations Rise in Asia

- Why do you think the teachings of Confucius were such a powerful influence on Chinese society?

- How was the Confucian civil service potentially more effective than rule by hereditary nobles?

- The Confucian civil service was a central feature of Chinese imperial culture for centuries. What were its advantages and disadvantages?

- Tempered Steel: A Conquered China

- What were the main positive and negative results of the Mongol conquest of China?

- The New Emperor

- How did the early Ming emperors try to change the society they ruled? Would you consider most of their changes positive or negative for the Chinese people?

- Zheng He

- What do you think was the most significant element of Zheng He’s seafaring missions?

- With such a commanding technological lead, why did China turn away from the outside world and suspend exploration?

- What might the world look like now, if the Chinese Empire had continued along the lines begun by Zheng He?

- The Start of Isolationism

- Discuss the symbolism of the Great Wall in Chinese culture.

- Does the size, complexity, and age of the Chinese Empire alter your understanding of the early modern world?

This chapter is an adaptation of Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- Terracotta_Army_Pit_1_-_2 © Maros M r a z is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Liji © snowyowls is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Half_Portraits_of_the_Great_Sage_and_Virtuous_Men_of_Old_-_Confucius © Anonymous is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Palastexamen-SongDynastie © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 4079285574_60bc820530_b © Ralph Repo is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Mongol_Empire_map © Astrokey44 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Marco_Polo,_Il_Milione,_Chapter_CXXIII_and_CXXIV © Marco Polo is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hongwu1 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 8139576703_a585a2d543_b © Keith Roper is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- OldmapofMecca © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Verbotene-Stadt1500 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license