8 Modern Crisis

Chapter Outline:

Unfortunately, and as mentioned in the last chapter, the end of World War I did not usher in a time of unending peace. It simply set the stage for World War II. However, this stage is set over a 20 year “peace” period… Hop on board and let’s find out what happened in those 20 years!

- The Horrors of War

- Hyperinflation

- The Soviet Union

- Rise of Fascism

- The Great Depression

- The Nazis

- China, Japan, & India

The horror of World War I was a shock to the self-satisfaction of Europeans who had believed themselves to be the pinnacle of world civilization. Intellectuals had shared in the celebration when war had been declared, parading in the streets of many national capitals. It is unclear exactly what they were expecting from the war, but their experience was quite different. No one exposed to the misery of trench warfare could hang onto illusions of the heroism and nobility of the struggle they were engaged in. The cold, the mud, and the terror of pointless charges over the top ordered by commanders who had no clue what they were doing and who rarely led their men into the slaughter – all these factors were captured by journalists and then by novelists like the American Ernest Hemingway (A Farewell to Arms, 1929), the German Erich Maria Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front, 1929), and the British Ford Madox Ford (The Good Soldier, 1915, and Parades End, 1925) and Robert Graves (Goodbye to All That, 1929).

The absurdity of Western culture was on display in what has come to be known as the modern crisis. The trenches had also been an unusual opportunity for the classes to mix. Some upper-class British officers such as Ford developed a new understanding of people they probably would never have met in their normal lives at home. Other novels dealing with these themes include German author Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain (1924), Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (published in England as the war was ending in 1918), and even Virginia Woolf’s most famous book, Mrs. Dalloway, where one of the main characters, Septimus Smith, is a war veteran suffering hallucinations caused by what we might now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); what was then called “shell-shock.” Smith avoids being committed to a mental institution by jumping out a window to his death.

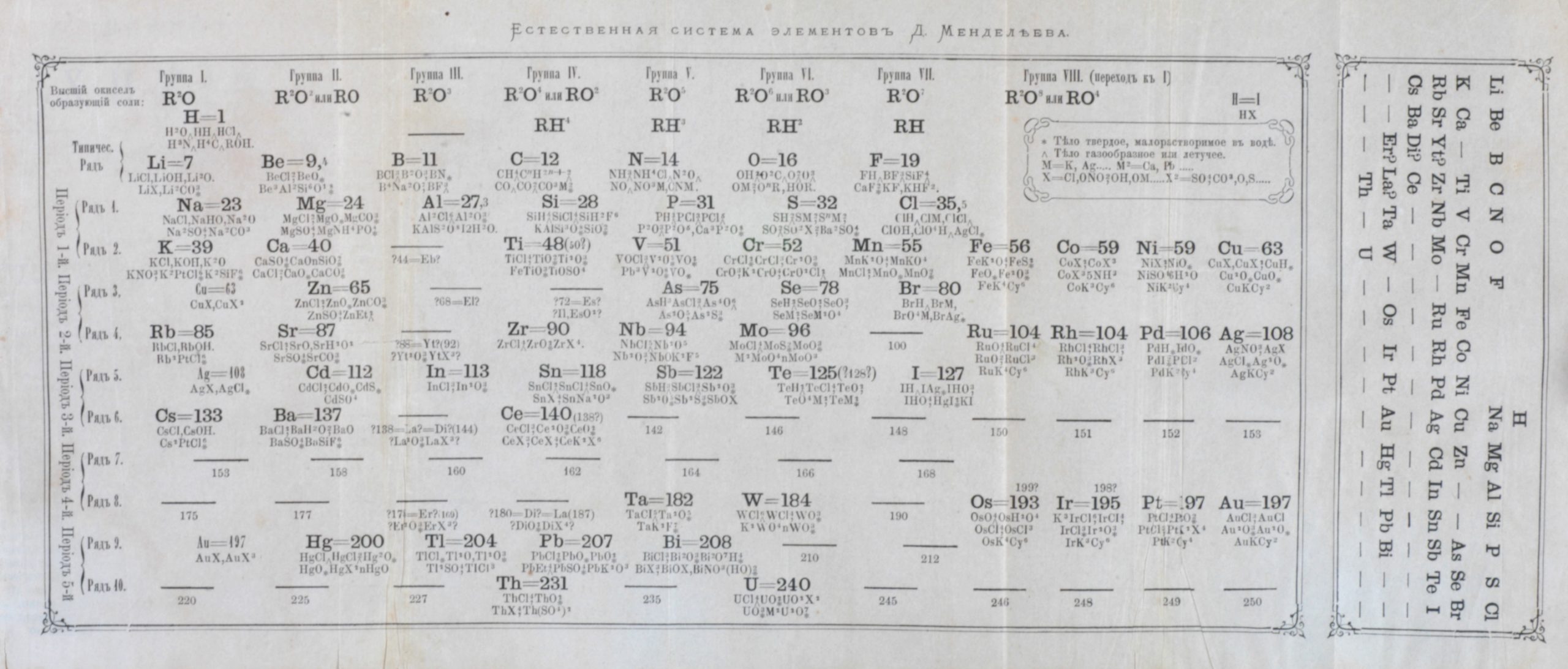

Alongside the novelists and intellectuals questioning the value of culture and social traditions that had led to the disastrous war, scientists were beginning to question the assumptions that formed the basis of our understanding of the universe. Since Newton, science had been pretty certain of the fundamental nature of reality. The atoms that were assumed to be the basic building blocks were imagined to function like little billiard balls, obeying all the laws of motion that scientists had studied in the “macro” world of regular experience. By the late 19th century scientists had discovered nearly 70 elements out of the 90 or so that occur naturally on earth. Russian scientist Dmitri Mendeleyev had explored the chemical nature of the elements and developed the periodic table that expresses their chemical relationships. On the other end of the spectrum, at the astronomical scale, the universe was believed to be made up of an eternal field of stars that spread in all directions.

This idea was challenged by Edwin Hubble’s discovery around 1925 that the Andromeda nebula, a fuzzy patch on the star maps, and other “spiral nebulae” were actually distant galaxies and that all the visible stars were just nearby members of our own, Milky Way galaxy. Hubble discovered more galaxies, and then used measurements of their Doppler shifts in light wavelengths to deduce that the universe was not steady and eternal, but expanding. Albert Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity suggested there were no static cosmological solutions, which led to the formulation of the Big Bang Theory (originally called the hypothesis of the primeval atom) by Belgian Catholic priest Georges Lemaitre.

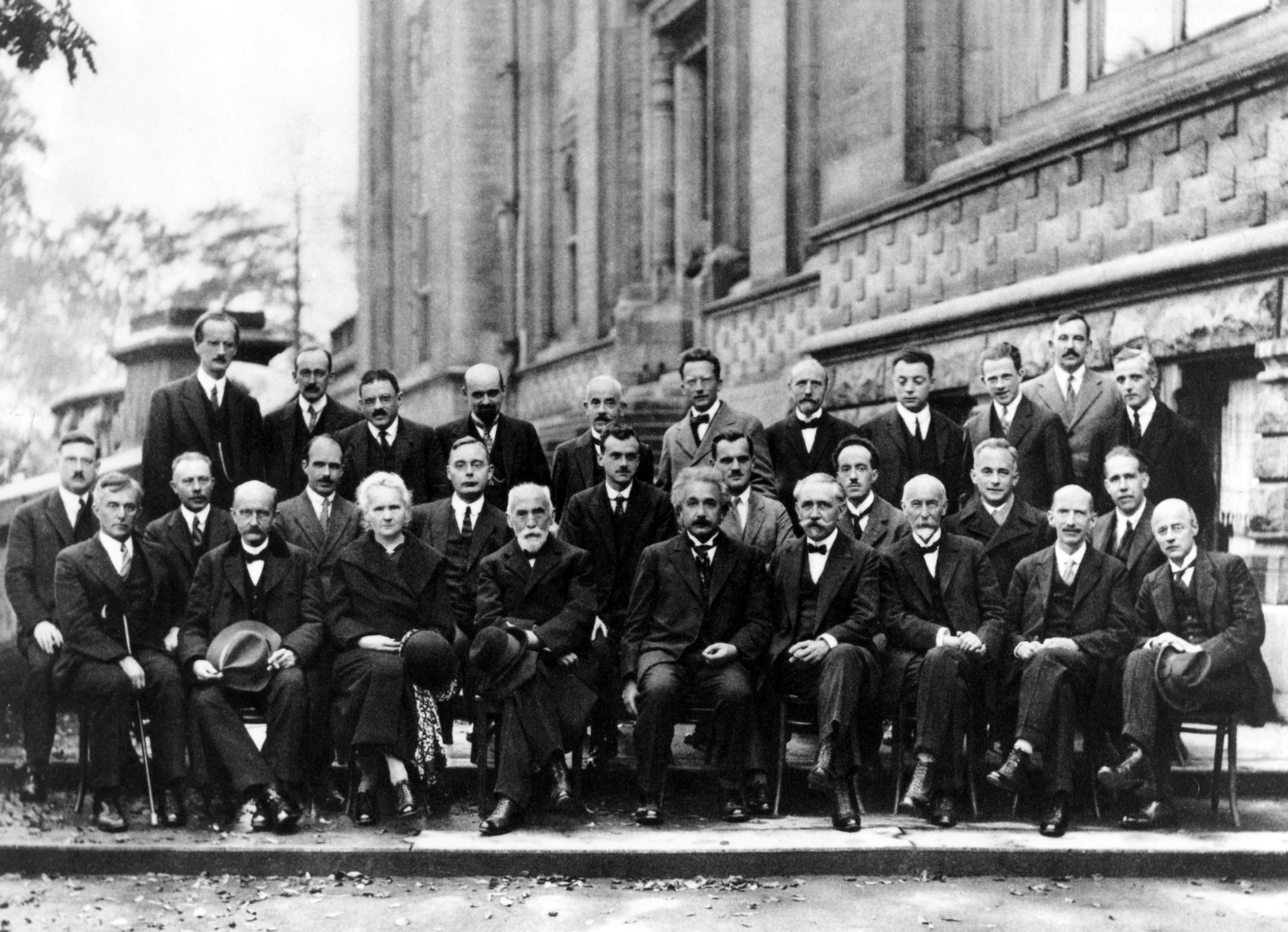

Atoms had been thought of as tiny billiard balls, obeying the basic laws of motion suggested by classical physics. Einstein challenged these ideas with his work on electromagnetics, and then Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, Louis De Broglie, and Erwin Schrödinger smashed the classical model entirely with their development of quantum mechanics. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle alerted the public that things were not what they appeared—that it was impossible to measure the position and velocity of a particle at the same time, and that the act of observation changes the process being observed. Others picked up on this idea, which became a metaphor for the intrusion of explorers and experimenters into the things they were exploring.

Even sociologists and anthropologists were influenced by the uncertainty principle, and began wondering how their arrival in people’s lives to gather data about their cultures actually altered those cultures. Psychologists Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung complicated matters even more when they suggested that there was a whole lot going on in the human subconscious over which we do not have control or even direct knowledge. The solid, rational basis of the western world was beginning to look like a house of cards or a shared hallucination that might evaporate at any moment.

The destruction of World War One, and the new ideas in science, sociology, and psychology led artists, architects, and filmmakers to reconsider “reality” as well. Already in the 19th century, the challenge and promise of industrialization, liberalism and nationalism had changed the themes traditionally considered by artists, while the attempt to get at the essence of a scene inspired painters to record their first “impression” of a scene, highlighting color and light over form. Even before World War I, the experimentation of the mainly French impressionists and post-impressionists (like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Vincent Van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin) inspired artists like the Norwegian Edvard Munch towards expressionism—using the impressionist style to express interior emotions. Munch’s “The Scream” from 1893 perhaps best sums up the “shock of the new” experienced not just by the artists but by much of society in the new industrializing world.

Abstract expressionism after the war reverted to forms and shapes to reveal interior thoughts and feelings, such as in Wassily Kandinsky’s “Yellow-Red-Blue” and Paul Klee’s “Ancient Sound”, both painted in 1925. The surrealist and Dadaist movements of the 1920s especially pointed to the absurdity of societal conventions, exploded in the carnage of World War I. The surrealists also focused on imagery inspired by Freud’s theories about dreams, such as René Magritte’s “The Menaced Assassin” from 1927.

Film-making had progressed quickly from simple experimental images in the late 1890s to more complex stories in the years leading up to the war, with directors like Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith taking the camera out of the theatre and introducing camera angles, close-ups, and moving carriages following the action, with editing to combine scenes into longer narratives. After the war, German expressionists produced the horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), using abstract sets to tell a story to criticize the insane authoritarianism they believed had directed society during the recent conflict. Other German directors like F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu, 1922 and Sunrise, 1927) and Fritz Lang (Metropolis, 1927 and M, 1931) also explored challenging themes in their films, while the Russian Sergei Eisenstein used metaphoric images and camera angles to tell stories of the workers’ struggle in The Battleship Potemkin and Strike (both released in 1925).

Hyperinflation

Peace began in Europe with the hope that the new nation-states that replaced the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires in Central Europe would deliver social justice and prosperity through new democratic constitutions. Not everybody was willing to wait patiently for life to get better after the war and pandemic, however. And the new Soviet Union, which had survived attempts by the allies and the U.S. to defeat the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War, felt justified in trying to export their “workers revolution” to the rest of Europe. Attempts at violent communist-inspired revolution led to violent reactions. Revolutionaries found support among the workers of many nations. Many believed the bloodbath in the trenches had to have meant something more than just gaining the right to vote—perhaps it was to birth a new socialist utopia, replacing the not just the monarchs who started the war, but the capitalists who profited from it.

In Germany, liberals and social democrats had declared a republic when Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated in the final days of World War I, with the hope that they could negotiate a peace as equals with the democratically-elected governments of Great Britain, France, and the United States. However, just weeks later, Bolshevik-inspired revolutionary actions like the Spartacist Revolt in Berlin were brutally suppressed by the new German government with the help of the paramilitary Freikorps—troops returning from the front who, having just fought for their nation, did not want Germany taken over by a “foreign” socialist revolution.

All the countries of Europe, both old and new, faced massive unemployment and inflation after the war as their economies readjusted and veterans returned to the workforce. However, these problems were magnified in Germany because on top of everything else, under the Versailles Treaty, the new government had to pay reparations to the Allies in the form of gold, coal and timber. By 1923, the Germans were unable to keep up with coal deliveries (any of the richest coal fields of Imperial Germany were now part of the new country of Poland); so French and Belgian troops moved in to occupy the northwestern Ruhr Valley, location of much of German industry. The German government encouraged a widespread strike to protest the occupation, which it funded by printing more paper money. Like nearly all of the world’s currencies, the German Deutschmark had originally been backed by gold, but the Kaiser had taken the country off the gold standard at the beginning of the war. Germany had expected to capture territory that would pay for its war expenses, but defeat and reparations changed the situation drastically. Printing more Deutschmarks decreased the value of each one, until ultimately they were not worth the paper they were printed on.

U.S. bankers, led by Charles G. Dawes, sat down with financial representatives of the other Allied powers to renegotiate German reparations. Dawes had helped secure the $500 million Anglo-French Loan and had then served as a General during the war. American financiers understood that a chaotically unstable German economy would never be able to pay indemnities to the British, French, and others, which made it more difficult for these Allies to cover their own debts to Wall Street. The solution Dawes negotiated was to have U.S. banks lend Germany the money it needed to keep up payments to the European Allies, who could then pay the Americans, who in turn could lend more to Germany. The arrangement brought economic and political stability to the Weimar Republic, and Dawes was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his work and became Calvin Coolidge‘s Vice President in 1925. The cycle of payments continued until the American banks were forced to stop lending at the beginning of the Great Depression.

The Soviet Union

Rise of Fascism

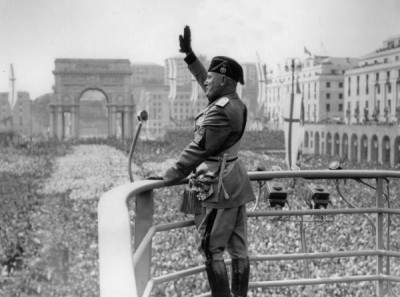

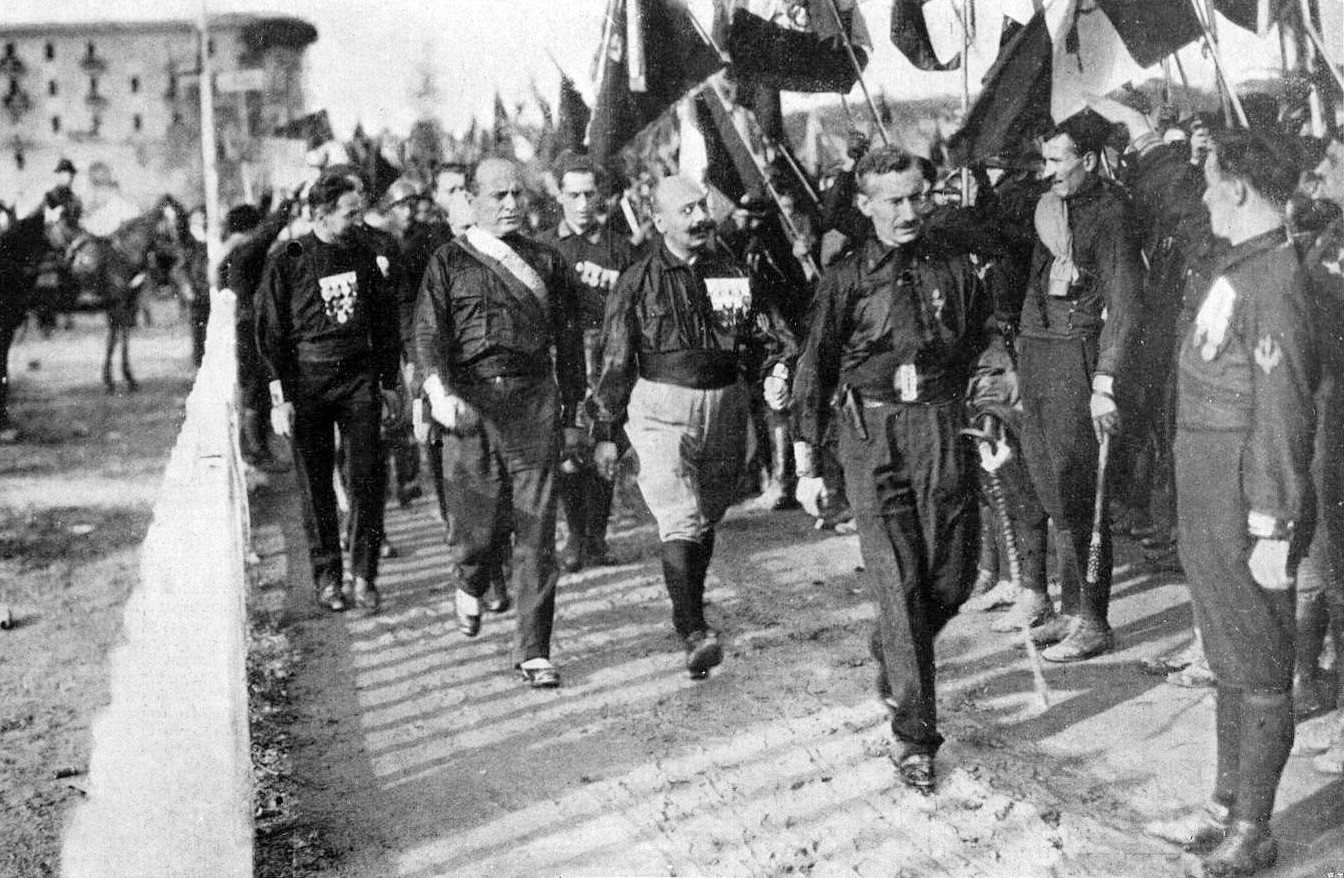

Like other European countries, Italy was disrupted by labor and socialist agitation after World War I. Strikes in the industrial north and agitation by landless peasants in the agrarian south were suppressed only with great difficulty by the government, a multi-party parliamentary democracy with a figurehead king. In October 1922, in the midst of yet another general strike, the Fascist Party, led by Benito Mussolini, marched on Rome. To prevent civil war, the King asked Mussolini to form a government. He would remain prime minister for the next twenty years.

Mussolini had begun his political career as a revolutionary socialist before World War I. However, he despised the pacifism of Italian socialism and became a convinced nationalist. He served in the war; like Germany’s Adolf Hitler, reaching the rank of corporal. Shortly after the war’s conclusion, he reentered politics, trading his previous socialism for a militarist nationalism in a new Fascist Party.

In addition to being anti-socialist, Fascism was anti-liberal and anti-democratic. Mussolini and his followers believed that parliaments were ineffective talk-fests of corrupt politicians that should be replaced by strong authoritarian leaders. Although fascists in Italy and the rest of Europe participated in elections, they did so with a high level of organized street violence by their own paramilitary units against political opponents; especially socialists and communists. Mussolini’s black-shirted squadristi were imitated by the Nazi brownshirts in Germany and the Falangist blue-shirts in Spain, among many others in the rest of Europe and the Americas. Not only did they break up rival political meetings, they also brutally attacked strikers and labor organizers.

By 1925, Mussolini had outlawed all other political parties and declared himself the supreme leader: Il Duce, in Italian. He went on to impose “totalitarianism”, his word for state control over the entire social and economic life of the nation. Claiming that they were protecting private property against socialism, fascists actually created a form of state corporatism that was every bit as autocratic as Stalin’s system but retained the appearance of private ownership. “Corporations” in this case means not only industrial companies, but also “corporate groups” of citizens based on their occupations, guilds, and associations. The leaders of these corporate groups represented their members in the national government, under “coordination” by the dictator. The establishment of corporate groups supported the claim that a wide array of political parties was no longer necessary; but in reality, the selection of leaders was limited to members of the official state party.

Mussolini and other fascists wanted to impose upon their countries military discipline and unquestioning loyalty to the leader. Imperial expansion became a priority and war was encouraged to bring grandeur to the nation and strengthen its people. Mussolini wanted to build a large army and navy to dominate the Mediterranean and to expand the Italian Empire—all to “make Italy great again.”

Fascism gained ground more slowly in most other countries in the 1920s, until the onset of the Great Depression. Italy did not seem to suffer as acutely from the social, labor and political unrest that came with the unexpected international economic crisis because the Italian opposition had been eliminated or jailed years before. For property-owners and capitalists, fascism was a defense against revolutionary communism, while even for some in the working class, it seemed to provide a degree of social and political stability that democracy was struggling to retain. This impression, even if it was not entirely accurate, did a lot to interest Italy’s neighbors in a political system that “made the trains run on time.”

The Great Depression

The exact causes of the Great Depression are still being argued by historians and economists. An ongoing agricultural recession in the United States and abroad during the 1920s was an important element, as was a Wall Street stock market bubble caused by excessive use of margin to buy company shares. Investors were able to buy the shares of companies for pennies on the dollar by borrowing 90% to 97% of the purchase price. This allowed them to buy ten to twenty times the number of shares they could actually afford, with lenders putting up the rest. This system works very well as long as prices continue to rise, and the extreme demand for stocks powered by margin-buying drove the prices ever higher. Insider trading was also quite common, with secret “pools” of investors buying up stocks to inflate prices, waiting for others to join in the game, and then selling when the price reached a profitable new height. During the 1920s, the value of the stock market doubled without a corresponding increase in corporation assets or earnings. The market grew at a rate of over 20% per year while the economy shrank. Most stock prices rose to levels that could not be explained by their assets or earnings, since industry was actually starting to feel the pinch of the agricultural recession. Stock prices typically reflect the underlying value of the company; in the bubble they mostly reflected the buying frenzy. When credit became a bit tighter and people began receiving margin calls and trying to sell more of these inflated shares than there were new buyers for, the bubble burst. Black Thursday was October 24, 1929, yet, it was only the beginning of a series of economic calamities.

In the United States, there were some who saw communism or fascism as a solution to all of the problems. However, U.S. democracy proved stable enough that the voters simply changed the party in power in the 1932 elections, from the Republicans to the Democrats. Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated president a few weeks after Hitler took power in Germany. Roosevelt was neither a communist nor a fascist, although he did accept a degree of government intervention in the economy to alleviate the worst effects of the crisis.

Franklin Roosevelt, born into an old, wealthy New York family, actually surprised many by embracing government intervention and regulation to address the ongoing Depression, and by spending government money to put people back to work. However, most people believed Roosevelt was “saving capitalism” rather than “imposing socialism.” Many New Deal agencies and programs are still with us today.

Roosevelt saw the role that Wall Street had in the crisis, and wanted to restore confidence in the banking system. This goal created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or FDIC as insurance. The FDIC was paid for by banks, which guaranteed that depositors would receive their savings (nowadays up to $250,000), in case of a bank failure. New regulations put an end to “pooling” and other forms of stock manipulation and insider trading, in order to restore confidence in the stock exchange. Borrowing money “on margin” to invest in stocks is still closely regulated. Finally, the Glass-Steagall Act prevented banks from dabbling in the securities and insurance industries—its repeal in the 1990s is seen as one of the causes of the 2008 Financial Crisis.

In agriculture, the Roosevelt Administration began paying farmers not to over-plant and stabilized farm prices with the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Agricultural Extension programs also taught new farming methods to prevent a future Dust Bowl.

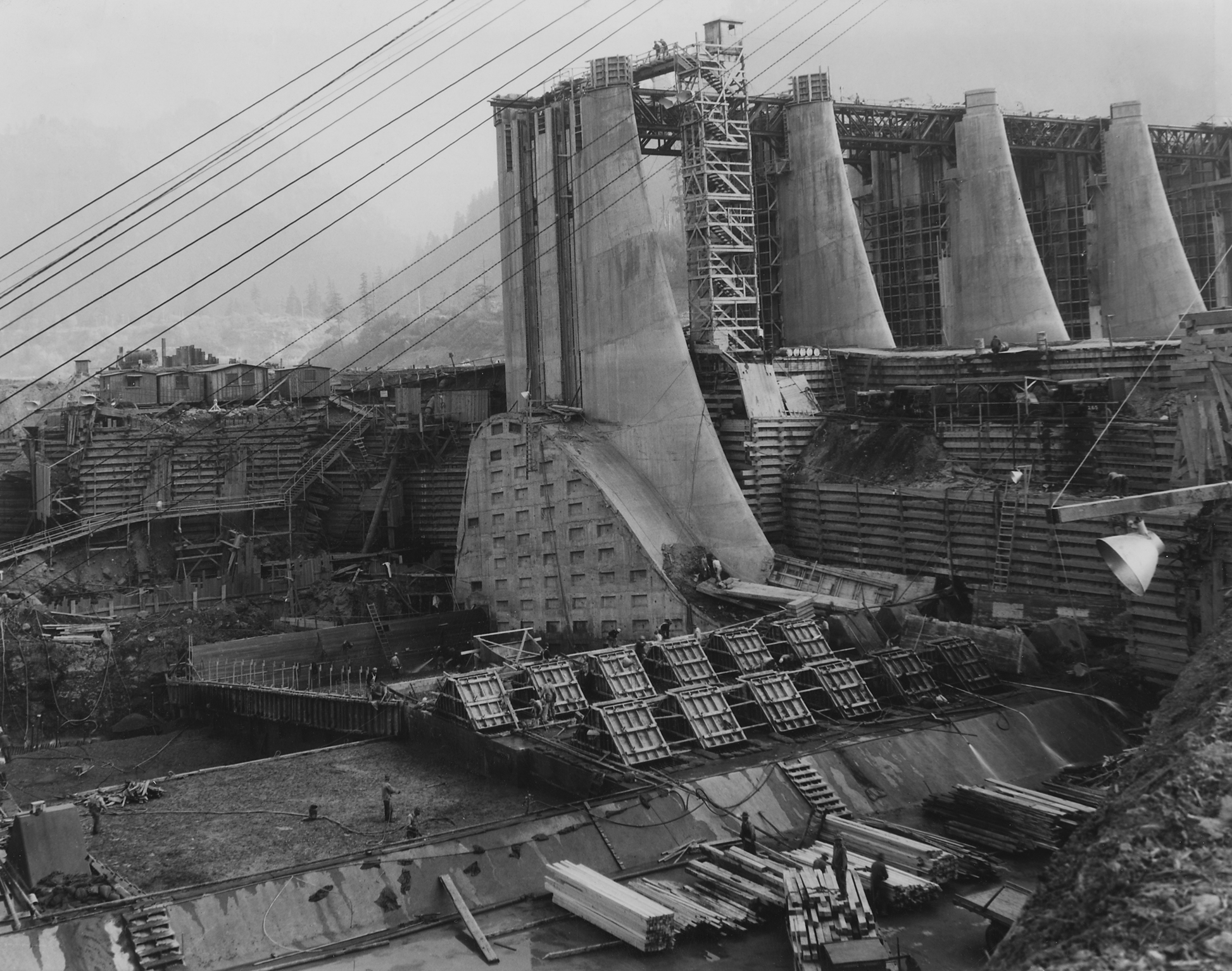

Federal government programs also put people back to work. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) included large building projects like the Hoover Dam and the Golden Gate Bridge, but also many smaller local projects like sidewalks, post offices and schools. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) attracted unemployed young men to mainly work on reforesting projects and improvements to national and state parks. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) focused on developing an entire region. TVA dams controlled the flow of rivers to prevent flooding and to provide electricity to factories and rural homes. Governments throughout the world sent representatives to see how it worked.

The Social Security System was established in 1935 to support widows and their children and to provide the elderly with a government pension so they would be able to retire without burdening their children. This opened jobs to younger workers, who could then afford a government-backed mortgage through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The Roosevelt Administration also encouraged labor union organizing under the Wagner Act. Instead of the government siding with industry and sending troops to put down strikes as in it had in the (recent) past, the Wagner Act legalized unions and strikes, and set up the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to arbitrate between industry and labor in contract disputes. Organized labor became an important political ally of Roosevelt and the Democratic Party as a result.

The Social Security System was established in 1935 to support widows and their children and to provide the elderly with a government pension so they would be able to retire without burdening their children. This opened jobs to younger workers, who could then afford a government-backed mortgage through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The Roosevelt Administration also encouraged labor union organizing under the Wagner Act. Instead of the government siding with industry and sending troops to put down strikes as in it had in the (recent) past, the Wagner Act legalized unions and strikes, and set up the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to arbitrate between industry and labor in contract disputes. Organized labor became an important political ally of Roosevelt and the Democratic Party as a result.

The Nazis

China, Japan, India

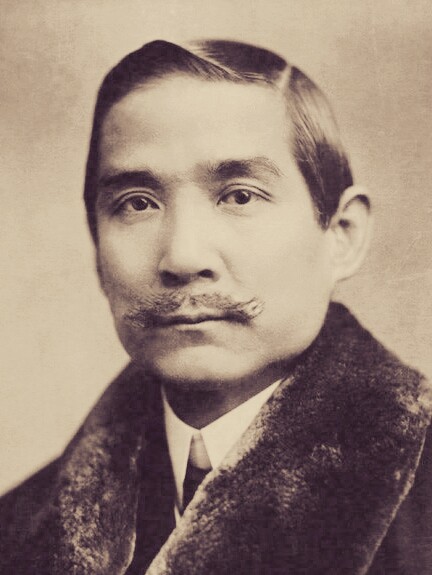

In 1911, Sun Yat-sen and his Xinhai Revolution finally overthrew the empire that had ruled China for over two thousand years, but the revolutionaries were not strong enough to install an effective government throughout China. Warlords brought order to the countryside and were not interested in respecting or supporting the new republic. In the power struggle between Sun Yat-sen and General Yuan Shih-kai, the head of the Imperial Army, Yuan won. Instead of Sun Yat-Sen, a warlord became president of the republic under the new constitution. In the chaos of the republic’s early years, remote imperial provinces were able to establish their own nations, separate from China. Mongolia is still independent, while Tibet was reconquered by Mao Zedong in the 1950s and is still seeking independence.

After Yuan’s death in 1916, cliques and civil conflict broke out between the republic and the warlords. Yuan had declared himself emperor in 1915, and additional provinces had broken away in protest. Sun and the nationalists experienced a resurgence on May 4, 1919, when students revolted in Beijing against the Versailles Treaty, in which Japan received the German protectorates in Shandong province, rather than China. These demonstrations marked an important modernizing moment for the new Republic. Later that year, Sun Yat-sen formed the Kuomintang (Nationalist) Party, inspired by the May 4th Movement. By 1921, Sun had reestablished the republic in Canton. Meanwhile, western-educated intellectuals had begun organizing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Shanghai, supporting Sun and the Kuomintang against the warlords.

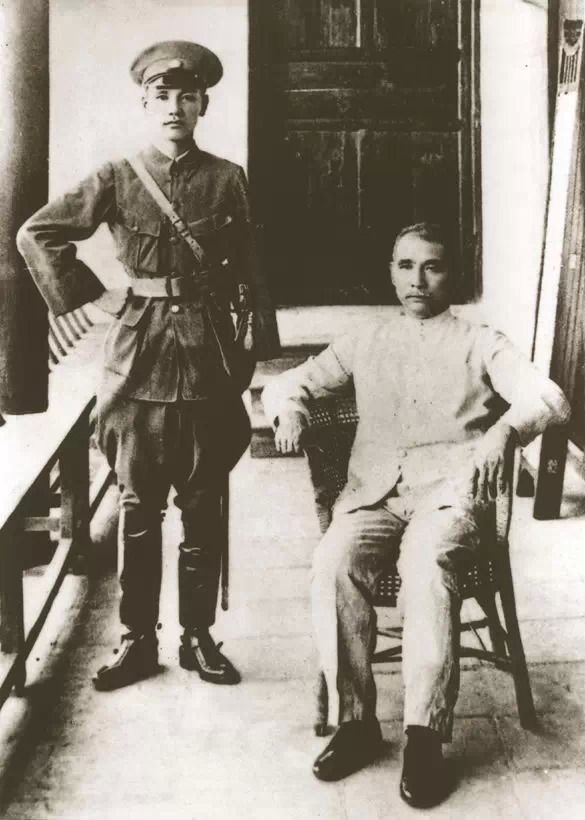

As the struggle continued against the northern warlords, Sun died of cancer in 1925, and his protégé, General Chiang Kai-shek took over the Kuomintang. Chiang was a capable leader who was able to unite the government. In 1927, Chiang married U.S.-educated Soong Mei-ling, the sister of Sun’s widow Soong Ching-ling. By 1927, the “Northern Expedition” against the warlords was successful, led by Chiang with CCP and Soviet support.

A few months later, however, a new civil war began in China. Chiang turned against his communist allies and began rounding up and executing many Communist leaders, while imprisoning others. In 1931, the Japanese military invaded Manchuria and created the puppet Kingdom of Manchukuo, installing the heir to the Qing dynasty, Pu Yi, as the monarch. The Chinese Republic, in the midst of a new civil war, was not in a position to fight the Japanese.

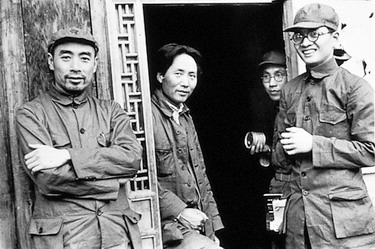

With so many communists imprisoned or executed, Mao Zedong, a charismatic leader of peasant origin, rose to prominence in the Chinese Communist Party by the early 1930s. The Nationalist armies reconquered parts of China’s interior under Communist control, surrounding the communists in the Jiangxi Province in October 1934. The CCP forces broke out of the trap and began what became known as the Long March. In 370 days, the communists covered 5,600 miles including some of the most rugged terrain in china. Mao Zedong gradually emerged as a leader of the CCP, along with Red Army leader Zhou Enlai. Zhou would become the first Premier of the Peoples Republic of China and Mao would become the Chairman of the CCP.

As seen in previous chapters, by embracing western technology and government, Japan went in the opposite direction of China in the late 19th and early 20th century. By 1910 the Japanese Empire had extended its territory to include the Ryuku Islands and Taiwan, had defeated the Russians in the 1905 war, and had taken control of the Korean peninsula. Japanese industrial goods, especially textiles, found markets in the U.S. and other parts of the world. And as part of the victorious Allied coalition in the Great War, the Japanese were awarded the Marshall Islands and Shandong peninsula from Germany, although their proposal to condemn racism was not approved by the Allied diplomats in Paris.

Japan enjoyed a parliamentary monarchy, with political parties, trade unions, a parliament, and a “divine” emperor. In international affairs, the civilian government joined the World War I allies in an effort to decrease the militarization of the Pacific and East Asia and agreed to maintaining a smaller navy in the Pacific than either the U.S. or Great Britain in the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. Increasingly ultra-nationalist officers in the army and navy were upset with the civilian government for negotiating the treaty. They advocated a Japan that would dominate East Asia, eventually replacing European rule and influence. “Asia for the Asians” was a motto they would use as they turned their attention to more regions that needed “liberating”.

As the reign of the new Emperor Hirohito began in 1926, the nationalist resurgence continued in the military, taking over Japanese foreign policy at the beginning of the Great Depression. The protectionism of many countries in the wake of the international financial crisis harmed the export-dependent Japanese economy. Ultra-nationalists in the military began advocating an extension of the Japanese Empire, following the example of the British in India. In 1931, an “incident” was staged by Japanese forces in Manchuria, giving Japan an excuse to take the region Manchuria from China. The civilian Japanese government was not in a position to reverse the conquest of Manchuria by their own military. Japanese diplomats ended up defending the takeover at the League of Nations.

In the following years, the nationalists gradually took control of the Japanese government, using the same anti-democratic, anti-Bolshevik rhetoric as the European fascists. In late 1936, Japan united with Germany in an Anti-Comintern Treaty in opposition to the Soviet Union and communism. The ideology of Japanese militarists similar to the Nazis in its racism: they believed that it was the destiny of the “Yamato” people to dominate East Asia and replace the Europeans, just as Hitler claimed a similar mantle for his pure “Aryans” in Europe. The Japanese Empire would bring order and prosperity to an Asia, “for the Asians” through the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japanese imperialism seemed like an attractive proposition to some in East Asia who wanted to rid themselves of European imperial rule.

As mentioned previously, the British trained and educated locals in India as soldiers, police, government administrators, and professionals in the nineteenth century in order to run the Empire, claiming they were preparing India for eventual self-rule. When the promised self-rule would begin became a source of debate and conflict between the colonizers and the colonized. In 1885, British-educated Indian reformers organized the Indian Congress Party to protest unfair treatment of Indians by British. They believed they were already administering the country and no longer needed British bureaucrats to tell them what to do. In 1909, British reforms provided for Indian representation in provincial legislatures, and as seen in the last chapter, Indian soldiers took part in many of the British campaigns during the Great War, especially in Africa and the Ottoman Empire. After the war, this service inspired increased agitation for independence. The politics of the Congress Party was greatly influenced by Mohandas Gandhi and his tactic of non-violent civil disobedience.

In 1916 the mostly-Hindu Congress Party united with Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League in a sincere attempt to create a party that represented all of British India.

Popular calls for complete independence from Britain were accelerated by the horrific Amritsar Massacre in 1919, a religious celebration which was interpreted as a political demonstration by the local British administrator, and which he ordered his troops to open fire on. Non-violently disobeying an absurd law effectively highlighted the futility of Britain’s position in India.

The British Parliament responded to the ongoing turmoil with the Government of India Act in 1935, which established regional legislatures. Voting was arranged by religious and social categories, applying a “divide and conquer” method that the British had been using since the 19th century. Focusing Indians on their religious differences would have disastrous long-term results, down to today. Nevertheless, the more inclusive Congress Party started winning regional elections in 1937.

It is important to consider that at a time when totalitarian fascism and communism were on the rise throughout much of the world, Gandhi and the All-India Congress Party presented the option of effective non-violent civil disobedience to achieve social goals. They were radically in favor of independence, but also encouraged democracy. The asceticism and simplicity of Gandhi was an example to be emulated, not a way of life imposed from above. Indian ideas and techniques would become an example for other struggles by colonized peoples and oppressed minorities, directly influencing the course of decolonization and the struggle for civil rights by African-Americans in the United States after World War II.

Knowledge Check:

Unfortunately, and as mentioned in the last chapter, the end of World War I did not usher in a time of unending peace. It simply set the stage for World War II. However, this stage is set over a 20 year “peace” period… Hop on board and let’s find out what happened in those 20 years!

- The Horrors of War

- Why were artists and authors thrown into a “modern crisis” after the Great War?

- How did science contribute to undercutting the sense of self-satisfaction felt by people before the “crisis”?

- Hyperinflation

- Why does printing excessive money affect prices?

- Why was it important to American bankers to save the German economy?

- The Soviet Union

- Why was it important for the Communist Party that it was remaining true to Karl Marx’s ideology?

- How do you think the Soviets were able to maintain power in light of all the people they were killing?

- Rise of Fascism

- Why were people in Europe and America not more alarmed by Italian Fascism?

- The Great Depression

- What is margin buying and how did it contribute to the Crash of 1929?

- What caused the Dust Bowl and how did it exacerbate the Great Depression?

- Do you think President Roosevelt went too far with his New Deal policies?

- The Nazis

- Why do you think Germans supported the Nazi Party?

- What were the Nazis’ motivations for targeting Jews and others for persecution?

- China, Japan, & India

- Why do you think the Long March is such an important element of the Chinese Communist Party’s history?

- Why did some Asians welcome Japan’s expanding empire?

- What elements of Gandhi’s approach to politics do you think were the most effective and memorable?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- EH 2723P © Ermeni Studios is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pic_iroberts1 © Isaac Roberts is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Metropolis_(German_three-sheet_poster) © Unkinown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-AlzadosEspartaquistas.

- Chas_G_Dawes-H&E © Harris & Ewing is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Benito_Mussolini_Roman_Salute © Daily Galaxy is licensed under a Public Domain license

- March_on_Rome_1922_-_Mussolini © Illustrazione Italiana is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Eritrean_Balilla © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Crowd_outside_nyse © US Gov is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PWAPBD_restored © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- SocialSecurityposter1 © US Gov is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dr._Sun_in_London © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sun_Yat-sen_and_Chiang_Kai-shek © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1937_Mao_Zhou_Qin_in_Yan’an © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emperor_Showa © 宮内省(Imperial Household Agency) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Manchukuo011 © Manchukuo State Council of Emperor Kang-de Puyi is licensed under a Public Domain license