7 The Great War

Chapter Outline:

Technological innovations and advancements along with revolutionary ideologies and chaos did not beget peace. The times discussed in chapters past have come to a head here in The Great War and as we know (and will see) the Great War becomes World War I. Strap yourselves in tight because this is going to be a bumpy and muddy ride!

- And So It Begins…

- Declaration of War

- The Technology of War

- The US Joins The War

- Mexico, Russia & The US

- Support for The War

- The Effects of War & “The Spanish Flu”

- Talks of Peace?

- War’s Aftermath

And So It Begins…

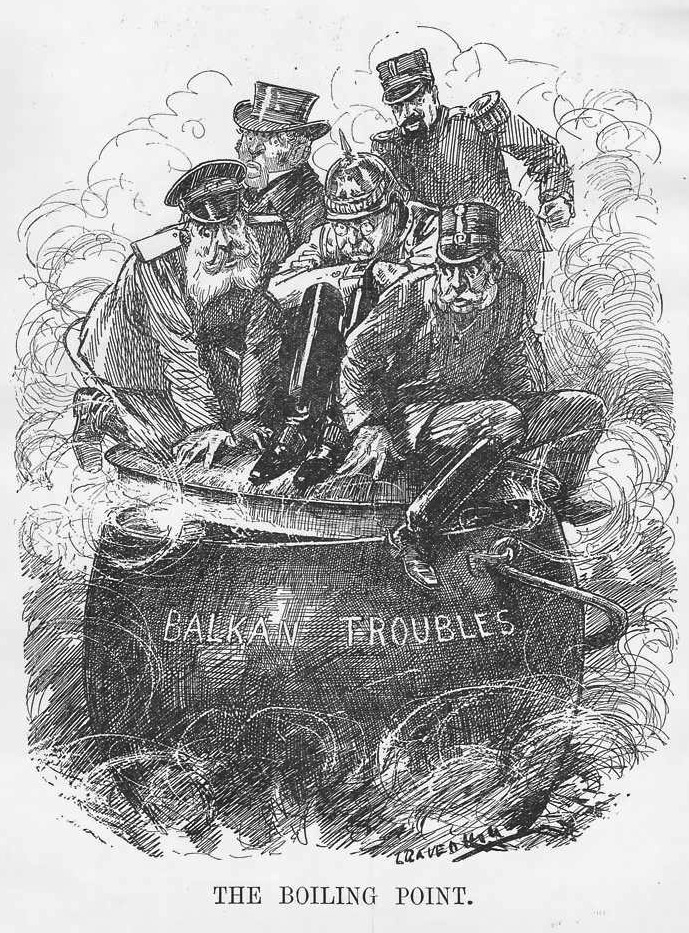

In 1914, Europe had been officially “at peace” for nearly a century. However, the official peace covered a growing tension that was beginning to flare up into military conflict. Unification of Germany in 1870, after the Prussian-led victory over the French, had created a new nation with imperial aspirations in the middle of Europe. Bismarck’s new nation competed with neighboring countries in industry, agriculture, and overseas empire-building. The existence of a strong, united Germany ended the careful balance of power created by the Congress of Vienna in its effort to reset the clock and redraw the map after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. France and Germany were enemies and sought alliances against each other. By 1914, most governments in Europe were preparing for an eventual war between these groups of allied nations, although no one knew what incident would bring the continent to battle. However, as early as 1888, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had predicted that “some damned foolish thing in the Balkans” could initiate a widespread European conflict. He was proven correct on the streets of Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

During World War One, the principal members of each of these alliances were the “Central Powers”, consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire against the “Allied Powers”, which at the beginning of the war was called the “Triple Entente” after the original allies, France, Great Britain, and Russia. Russia left the war in 1918, Italy joined the allies in 1915, and Japan was an additional ally on the French side. The United States entered the war to support the allies in 1917.

The underlying causes of World War One were nationalism, opposition to foreign rule, and simmering rivalries between the Great Powers that were exacerbated by treaties requiring allies to enter a war once it began. Previously, potential world conflicts had been avoided through negotiation among the Powers. Africa was divided among the European empires at the Berlin Conference in 1885, while “Spheres of Influence” were established in China in order to regulate trade. However, such a “Concert of Nations” did not succeed in the Balkans.

The unification of Germany upset the balance of Europe. Not only did the Deutsches Reich aspire to become an imperial power like Britain, France, and Russia, it had rapidly built up its military and industrial power. By the first two decades of the twentieth century, Germany surpassed Britain to become the largest economy in Europe and second in the world. German scientists won more Nobel Prizes than any other nation beside the United States. By 1914, the German navy was second only to the British Royal Navy. The new German emperor also dismissed Bismarck as Chancellor in 1890 and began looking for ways to make Germany a colonial empire, through a much more aggressive foreign policy than that envisioned by his chief advisor.

We must, however, understand that by the end of the nineteenth century, newly-independent nations of Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Montenegro and Serbia separated the Muslim Ottomans from the Catholic Austro-Hungarians. The Orthodox Russians dreamed of reestablishing Constantinople in Istanbul, and felt a kinship with their fellow Orthodox Slavs, the Serbs and Bulgarians.

The Balkan conflict Bismarck had predicted began in 1908 with the Austro-Hungarian takeover of Bosnia from the Ottoman Empire. Many Serbs lived in Bosnia, so Serbian nationalists wanted it to be part of Serbia. The Serbs and Bulgarians deepened their alliance with the Russians, who also wanted to check the expanding influence of the Austrians in the Balkans.

The independent nations of the Balkans fell into war in 1912-1913, first with the Ottomans, resulting in an independent Albania, and then with each other as ethnic and religious boundaries were contested. These were bloody conflicts that included attacks on civilian populations in waves of ethnic cleansing—people living in this region would experience similar massacres in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. The Balkan armies on both sides dug into trenches as new arms and technology limited the movement of troops.

In an effort to strengthen Bosnian ties to Austria, Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife made an official visit to the regional capital of Sarajevo on June 30, 1914. A secretive Serbian nationalist group, that had been encouraged and supported by Serbian military officers, plotted the assassination of the royal couple as their motorcade made its way through the city. After some initial bungling, one of the conspirators, nineteen-year-old Gavrilo Princip, shot and killed the Archduke and his pregnant wife.

The Austro-Hungarian government made a series of demands for restitution from the Serbian government. When Serbia refused, Austria decided to invade. Germany was bound by its treaty obligations to support any action taken by its ally Austria-Hungary. Austria’s invasion of Serbia activated the European alliance system: Russia sided with the Serbs, France supported Russia, and Great Britain was allied with France.

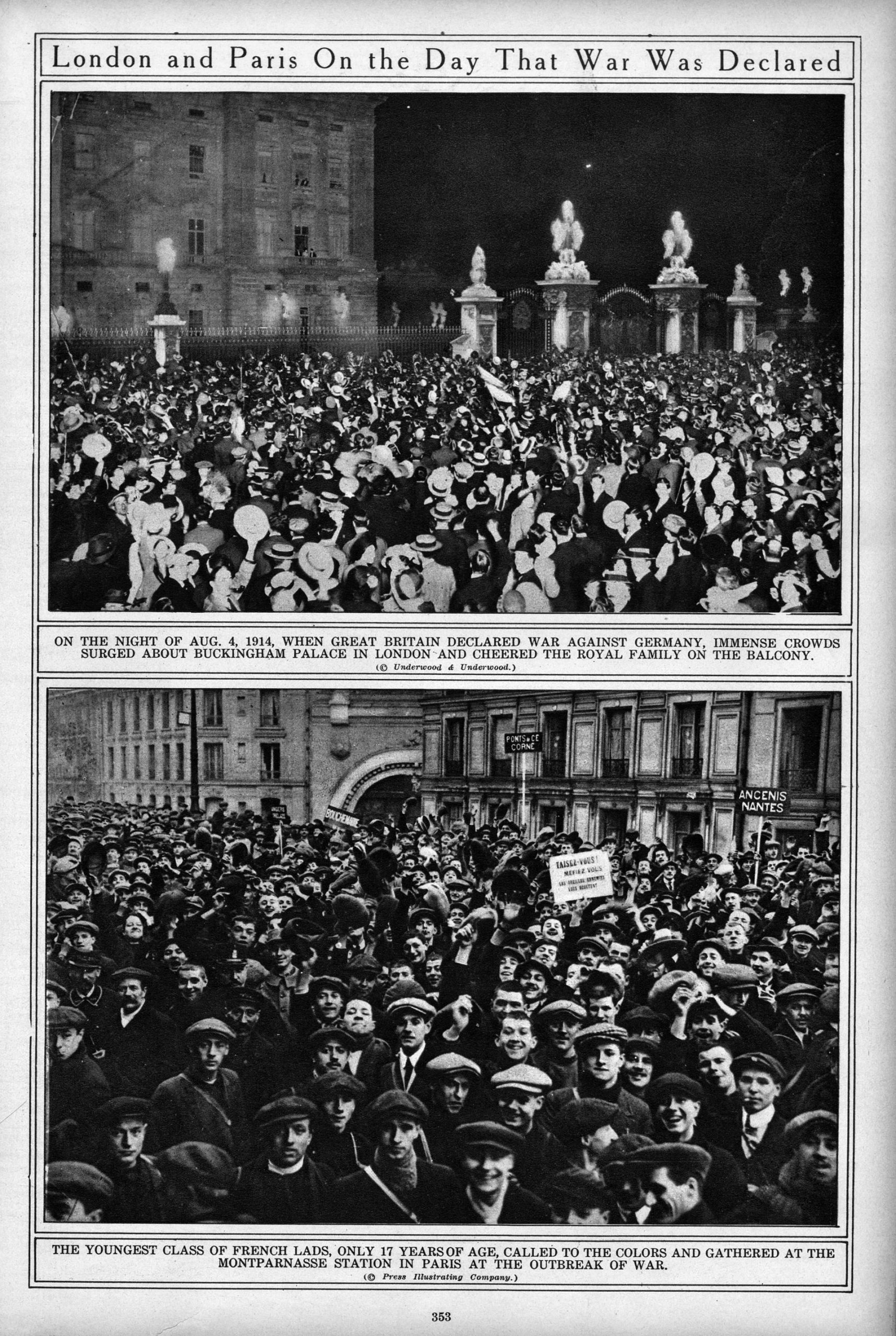

Deceleration of War

All of Europe’s armies had been preparing for a continent-wide conflict since the unification of Germany in 1870. Most nations required some form of military service from all young men, so that thousands of trained reserve soldiers could be quickly called up. This rapid deployment meant that as soon as one side mobilized, the opposing side also had to mobilize in defense. Less time was available for calm decision-making as every nation rushed to arms. In July 1914, when Austria declared war and shelled the Serbian capital, Belgrade, Russia mobilized its military. Germany mobilized against Russia. Russia was allied with France, so France mobilized. Great Britain was allied with France, so Great Britain mobilized. The Ottomans sided with Germany as a counter to Russia. Italy, which had a defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, sat out of the first months of war, until its government decided to side with France, Great Britain, and Russia in early 1915.

With the French-Russian alliance in mind, the German generals had been planning for years to initially fight a defensive war with Russia in the east and an offensive war with France in the west; holding off invading Russian armies while focusing on defeating the French first.

In the first months of the war, the Germans were successful in carrying out their strategy. The German army on the eastern front was able to stop and even defeat the advancing Russians. On the western front, the German government asked permission of neutral Belgium to pass through on their way to a surprise attack on France. When the Belgians rejected the request, German troops invaded and occupied Belgium in August 1914. The Germans advanced rapidly into France, but were halted by combined French and British forces, miles from Paris. Both sides dug in, creating a network of opposing trenches that ultimately extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Armies on both sides would be frustrated in their attempts to break through on this “western front” for the next four years.

Advances in military technology caused the stalemate. Conflicts like the Crimean War and the U.S. Civil War had begun introducing better, more deadly weapons. The Charge of the Light Brigade had proven that cavalry was ineffective against dug-in artillery. And in the last decades of the nineteenth century, Europeans had perfected the use of machine guns, practicing on native populations in their colonies. By 1914 the armies of Europe had better weapons and better defenses: long-range artillery, machine guns, trenches, and barbed wire. And they were ready to use these on each other, rather than just on the so-called “barbarians” their empires ruled over.

Since neither cavalry nor infantry could stand against machine guns, attacks in trench warfare began with massive artillery barrages to “soften” the other side before troops were sent out of their trenches, “over the top” into the no-man’s land between their trenches and those of the enemy, with fixed bayonets to overwhelm any enemy soldiers who had survived the shelling. When their artillery had not “softened up” the opposing forces enough, attackers would be met with enough machine gun fire to slow down any effective advance. During four long years of war, millions would either be severely wounded or killed in the “no-man’s-land” that separated the opposing armies.

The Technology of War

Airplanes, first developed by the Wright Brothers in 1903, proved their value in reconnaissance and later in strafing trenches with machine guns and dropping small bombs. Poison gases added another devastating weapon to trench warfare, while achieving no significant advantage. At least 1.3 million people were killed by gas attacks. Chlorine and mustard gas were two of the most common chemical weapons used by both sides in the war. In the case of mustard gas poisoning, the effects took 24 hours to begin and could take 4-5 weeks to die.

Even before the entry of the United States in 1918, the war had become truly global. Japan was eager to be counted as a world power, and Japanese leaders seized upon the opportunity the war provided to improve their status in Asia. After taking control of German colonies in China and the Pacific in 1914, Japan sent the Chinese government a list of 21 Demands. The Chinese believed that giving in to Japan’s demands would have basically resulted in China becoming a colony of the Japanese Empire. The Chinese government agreed to some of the demands, but leaked the list to British diplomats, who intervened to prevent a complete shift in the balance of power in Asia.

In Africa, Germany lost its colonies in the fighting. The German commander in East Africa, led a largely native African force in guerrilla tactics against Allied troops for most of the war. In eastern Africa, disrupted crop cultivation led to hundreds of thousands of deaths by starvation and disease.

The Ottoman Empire controlled territory on either side of the Bosporus straits, which connects the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. In 1915, the Allies landed troops at Gallipoli, a peninsula on the European side of the Bosporus, about 200 miles (320 km) from the Ottoman capital in Istanbul. The plan was to take Istanbul, knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war and open a third front against Austria-Hungary and Germany through the Balkans. However, the Turks held the high ground above the landing site chosen for the mostly colonial troops. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) troops were decimated, in a battle that marks the beginning of a sense of nationality in those countries. The anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, April 25th, is still celebrated as ANZAC Day. The disastrous plan nearly ended the political career of the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

The eleven month-long Gallipoli invasion was even more important for the Turks. The hard-fought victory was led by General Mustafa Kemal, who soon became a national hero and would go on to found the modern Turkish Republic and serve as its first president after the war.

Yet, at nearly the same time as the Gallipoli landings, the Ottoman government also decided to take action against the Christian minority in Armenia. Armenians had suffered from periodic pogroms in the decades preceding World War One. The Armenians were loyal subjects (many were serving in the army when the persecution began), but after an unsuccessful Russian attempt to invade Turkey from the east, some military leaders in the Turkish government accused the Armenians of collaborating with the Russian troops and decided to eliminate the Armenian population. Men were executed, while women and children were force-marched across the desert to Mesopotamia. Nearly one million died in what was the worst genocide of the 20th century before the Holocaust of World War II.

The imperial powers drafted soldiers from their colonies into the fight. Many of the 18 million people killed in battle and 23 million wounded, were people ruled by the empires. Over 700,000 Indians fought for Britain against the Ottomans in Mesopotamia. Indian divisions were also sent to Gallipoli, Egypt, German East Africa, and Europe. At least 74,000 Indians died in World War I.

Despite all of the efforts for a breakthrough on the battlefields of France and Eastern Europe, the most effective strategy against Germany was the British-led naval blockade, which cut off grain and other food supplies from overseas. The Germans, who had developed the most effective submarines and torpedoes, tried to blockade Great Britain and France by sinking incoming supply ships. This German naval strategy, however, risked bringing the United States into the war. After the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915, when a hundred U.S. citizens were drowned a few miles from the Irish coast, some American public opinion began to shift in favor of entering the conflict. The German government quickly backed away from unrestricted submarine warfare against supply ships bound for the Great Britain and France.

The U.S. Joins The War

The United States had a long tradition of trying to avoid being drawn into the “Great Powers” conflicts of Europe. American attitudes toward international affairs reflected the advice given by President George Washington in his 1796 Farewell Address, to avoid “entangling alliances” with the Europeans. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 had gone further to establish the Western Hemisphere as the United States’ area of interest, implying that the U.S. did not intend to intrude in the affairs of Europe. However, although the U.S. did not participate in international diplomatic alliances, American businesses and consumers benefited from the trade generated by nearly a century of European peace and the expansion of the transatlantic economy.

Additionally, by the 1880s and 1890s, millions of Europeans emigrated to the United States to work in factories and mines, or to establish farms in the West. More Irish and Germans arrived, and also Swedes, Norwegians, Finns, Poles, Ukrainians, Italians, and Jews from Eastern Europe. The U.S. needed and (largely) welcomed the newcomers, while America served as a “safety valve” for European nations with an excess of poor landless peasants. The diversity among the immigrants in this American “melting pot” helped bolster the case for U.S. neutrality in European affairs even as the war began.

A foreign policy of neutrality also reflected America’s focus on the building of its new powerful industrial economy, financed largely with loans and investments from Europe and especially London. However, U.S. dependency on foreign capital began to change during the war, when American bankers began making substantial loans to Britain and France. John Pierpont Morgan’s successor, J.P. Morgan Jr., who had spent the early years of his career managing the family’s bank in London, leveraged a friendship with British Ambassador Cecil Spring Rice to have the Morgan bank designated as the sole-source U.S. purchasing agent for both Britain and France. J.P. Morgan and Company managed the Allies’ purchases of munitions, food, steel, chemicals, and cotton; receiving a 1% commission on all sales. Morgan led a consortium of over 2,000 banks and managed loans to the Allies that exceeded $500 million (nearly $13 billion in today’s dollars). Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, the populist-leaning William Jennings Bryan, objected to the loans and that by denying financing to any of the belligerents, the U.S. could hasten the end of the war. Yet, a quick end was not the goal at all! As Thomas Lamont presented, the best result for America would be a long war that ended in German defeat and left the winners deeply in debt to the United States.

Lamont’s prediction came true. Wall Street, in New York City, became and remains the financial capital of world, with international debt denominated in U.S. dollars, largely because of the loans made to the European Allies during World War I. U.S. agriculture also benefitted from the war raging in Europe. Drafted farmers could not farm and soon grain from the Great Plains of the United States was feeding British and French troops on the Western Front; bringing wealth to Midwestern agricultural communities. Farmers were soon purchasing new equipment and buying or renting additional land to produce more.

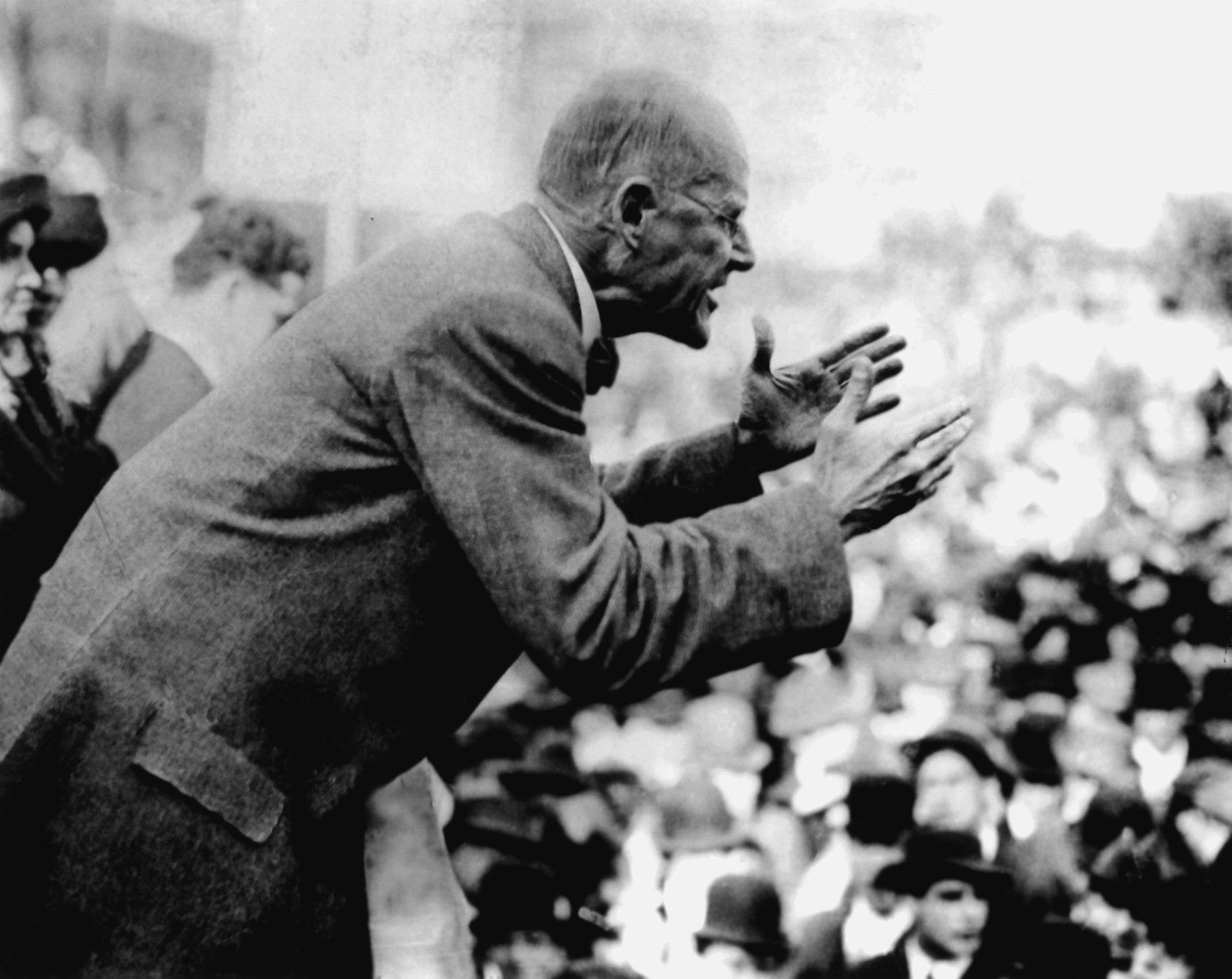

Despite Wall Street bankers’ interest in profiting on the European conflict, the U.S. federal government faced strong public opinion against entering what Americans saw as a fight they had no stake in. Business leaders and social activists like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Ford, and Jane Addams were pacifists. Poor southerners reminded America that “a rich man’s war meant a poor man’s fight”. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, denounced the war in 1914 as “unnatural, unjustified, and unholy.” And socialist pamphlets argued that “a bayonet was a weapon with a worker at each end.” Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” Yet, a month after his second inauguration, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

Mexico, Russia, & The US

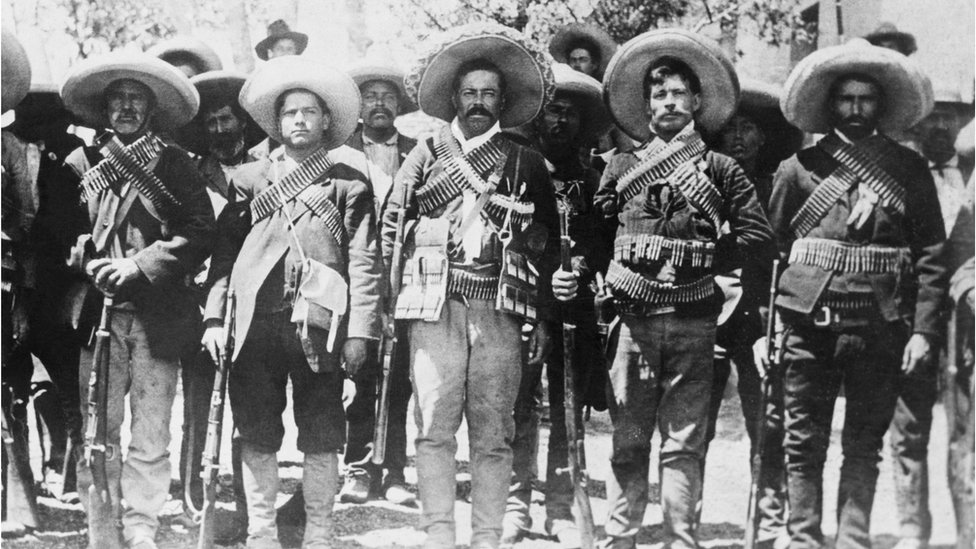

The European powers had been building up their military capabilities for nearly a generation before the outbreak of war, and it was unclear whether the United States could mobilize rapidly. In late 1916, border troubles in Mexico served as an important field test for modern American military forces and the National Guard. Revolution and chaos threatened American business interests when Mexican reformer Francisco Madero challenged Porfirio Diaz’s corrupt and unpopular conservative regime. Madero was jailed, fled to San Antonio, and planned the Mexican Revolution. Although Díaz was quickly overthrown and Madero became president, the Revolution unleashed forces that demanded more social change, especially in land reform, that the new liberal government was capable of delivering. New uprisings, led by Pancho Villa and Emilio Zapata, broke out in rural Mexico. Reactionaries assassinated President Madero in Mexico City in early 1913, with the encouragement of the European and U.S. ambassadors, and a military regime was installed—but social upheaval and a guerrilla war continued.

Liberal reformers soon established a republic, which actually made it easier for U.S. President Wilson to proclaim that the war was to “make the world safe for democracy,” since a major ally was no longer ruled by an absolute monarch. However, the democratic reformers in Russia were not as well organized as socialist revolutionaries led by Vladimir Lenin, who saw the end of tsarist rule as an opportunity to also defeat capitalism and creating a “dictatorship of the proletariat”. The revolutionaries and the soldier and sailors who supported them wanted to end Russian participation in the war.

The Russian revolution soon became a civil war between the “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army”, formed by the Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky, and the armies of the “White Russians” under several leaders, dedicated to restoring the Tsarist monarchy. To prevent the return of the Romanovs to power, the revolutionaries had the entire family killed in July, 1918. The revolutionaries also waged war on uncooperative peasants called Kulaks, whom they accused of withholding grain from the Bolshevik government. Many of the Kulaks were Ukrainian, which contributed to an ongoing aggression toward the Ukraine by the new Soviet Union.

The Russian revolution soon became a civil war between the “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army”, formed by the Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky, and the armies of the “White Russians” under several leaders, dedicated to restoring the Tsarist monarchy. To prevent the return of the Romanovs to power, the revolutionaries had the entire family killed in July, 1918. The revolutionaries also waged war on uncooperative peasants called Kulaks, whom they accused of withholding grain from the Bolshevik government. Many of the Kulaks were Ukrainian, which contributed to an ongoing aggression toward the Ukraine by the new Soviet Union.

Even after World War One ended, the Allies, including the United States, supported the White Russians against the Bolsheviks, sending thousands of troops to support the counterrevolutionaries in Siberia between 1918 and 1920. Years later Josef Stalin, who fought on the Soviet side in the civil war, would remember this fact while negotiating with Britain and the U.S. during World War II.

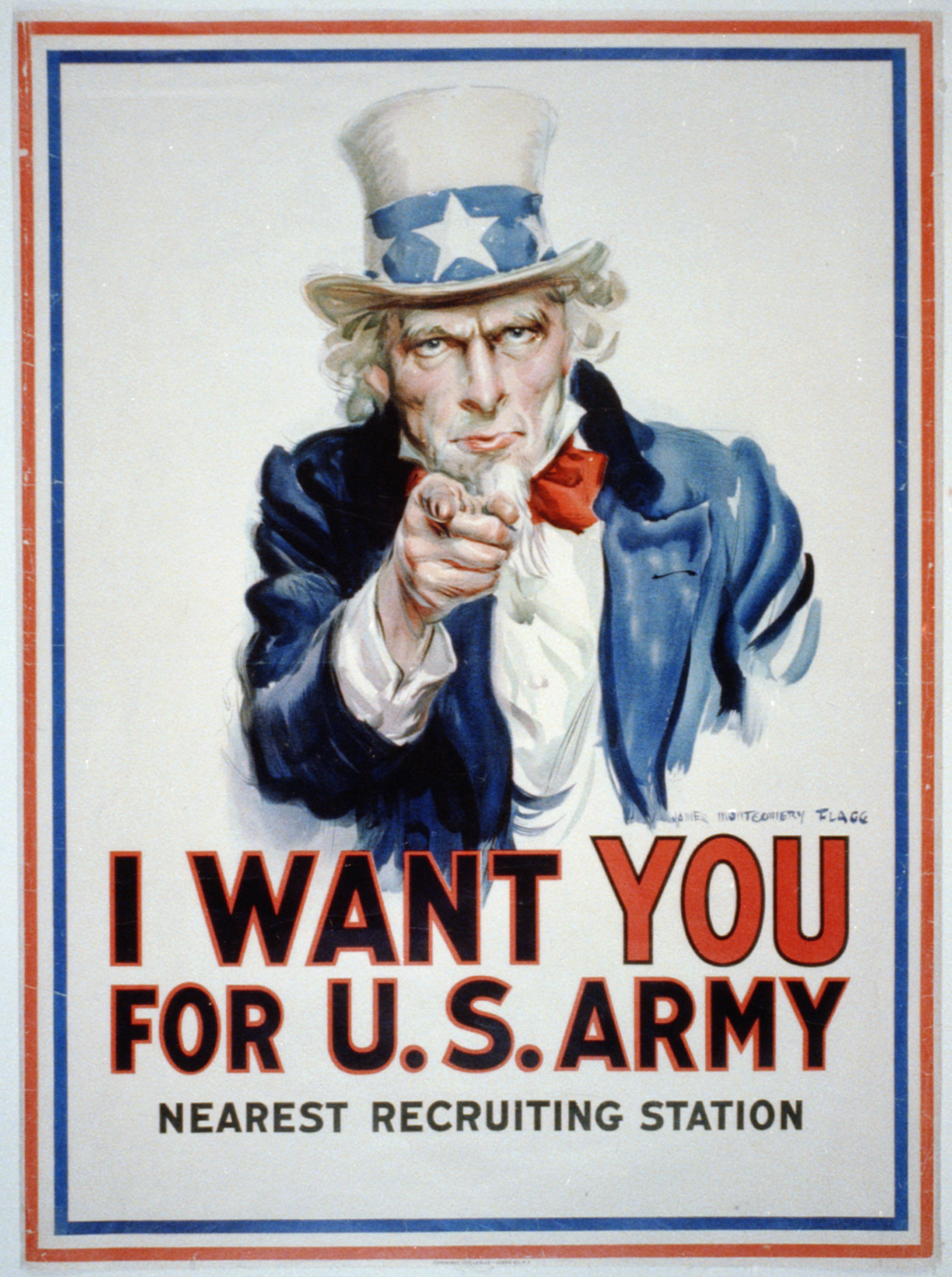

Support For The War

As soon as the war began, governments on both sides moved quickly to portray the war effort as a success and to eliminate any sign of dissent. Britain censored mail sent by soldiers at the front to their families, instituting standardized postcards that allowed men in the trenches to choose from a menu of statements but not to write anything specific about their experiences. Society became completely focused on the war effort, and governments reorganized the economy around war production. The state also rationed food and strictly controlled the media (which at the time meant the press) to silence dissent and present news of the war that boosted the morale and resolve of the population.

The US government launched several laws to keep possible dissents in check. By 1919 even the authorities realized they had gone too far, and the U.S. Attorney General convinced President Wilson to commute the sentences of 200 prisoners convicted under the acts.

On another note, women on all sides served as nurses and medics, and worked in agriculture and industry to keep the economy going while men were away fighting. Many governments promised equal pay, although most did not make good on their promise. But women gained political influence, and achieved the right to vote in the U.S. and many European countries almost immediately after the war’s end as a result of their contributions to the war effort.

The Effects of War & “The Spanish Flu”

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war, with its advanced artillery, machine guns, poison gas, and submarines. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against German submarine attacks, which had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly, just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although many of the supplies still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to be a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war, with its advanced artillery, machine guns, poison gas, and submarines. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against German submarine attacks, which had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly, just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although many of the supplies still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to be a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

In March 1918, Germany tried to take advantage of the withdrawal of Russia and its new single-front war before the Americans arrived, with the Kaiserschlacht (Spring Offensive), a series of five major attacks. By the middle of July 1918, each and every one had failed to break through the Western Front. Then, on August 8, 1918, two million men of the American Expeditionary Forces joined the British and French armies in a series of successful counteroffensives that pushed the disintegrating German lines back across France. The gamble of the Spring Offensive had exhausted Germany’s military, making defeat inevitable. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated at the request of the German military leaders and a new democratic government agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918, hoping that by embracing Wilson’s call for democracy, Germany would be treated more fairly in the peace talks. German military forces withdrew from France and Belgium and returned to a Germany teetering on the brink of chaos. November 11 is still commemorated by the Allies as Armistice Day (called Veterans’ Day in the United States).

In all between 16 and 19 million soldiers died in World War I along with 7 to 8 million civilians (before the influenza pandemic of 1919). Some of the worst battles were:

- Verdun: 976,000 casualties (Feb.-Dec. 1916)

- Brusilov Offensive: Nearly 2,000,000 casualties (June-Sept. 1916)

- Somme: 1,219,201 casualties (July-Nov. 1916)

- Passchendaele: 848,614 casualties (July-Nov. 1917)

- Spring Offensive: 1,539,715 casualties (March 1918)

- 100 Days Offensive: 1,855,369 casualties (Aug.-Nov. 1918)

Civilian populations were also targeted. While bombing cities from airplanes was much more common in World War II, naval blockades were also an effective way of putting pressure on civilians. Even if a nation was relatively self-sufficient in food production under normal circumstances, war was not a normal circumstance. The British blockade of Germany prevented not only war supplies but food from reaching the German people, resulting in a half million civilian deaths. For the Europeans, World War I was a “Total War” involving every level of society.

By the end of the war, more than 4.7 million American men had served in all branches of the military. The United States lost over one hundred thousand men, fifty-three thousand dying in battle and even more from disease. Their terrible sacrifice, however, paled before the European death toll. After four years of stalemate and brutal trench warfare, France had suffered almost a million and a half military dead and Germany even more. Both nations lost about 4 percent of their populations to the war. And death was not nearly done.

Talks of Peace?

On December 4, 1918, President Wilson became the first American president to travel overseas while in office. Wilson went to Europe to end “the war to end wars”, and he intended to shape the peace. The German, Russian, Austrian-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires each evaporated and the map of Europe was redrawn to accommodate new independent nations. As part of the armistice, Allied forces occupied territories in the Rhineland separating Germany and France, to prevent conflicts there from reigniting war. A new German government disarmed while Wilson and other Allied leaders gathered in France at Versailles to dictate the terms of a settlement to the war. After months of deliberation, the Treaty of Versailles officially ended the war.

In January 1918, before American troops had even arrived in Europe, President Wilson had offered an ambitious statement of war aims and peace terms known as the Fourteen Points to a joint session of Congress. The plan not only addressed territorial issues but offered principles on which Wilson believed a long-term peace could be built. The president called for reductions in armaments, freedom of the seas, adjustment of colonial claims, and the abolition of the types of secret treaties that had led to the war. Some members of the international community welcomed Wilson’s idealism, but in January 1918, Germany still anticipated a favorable verdict on the battlefield and did not seriously consider accepting the terms. Even the Allies were dismissive.

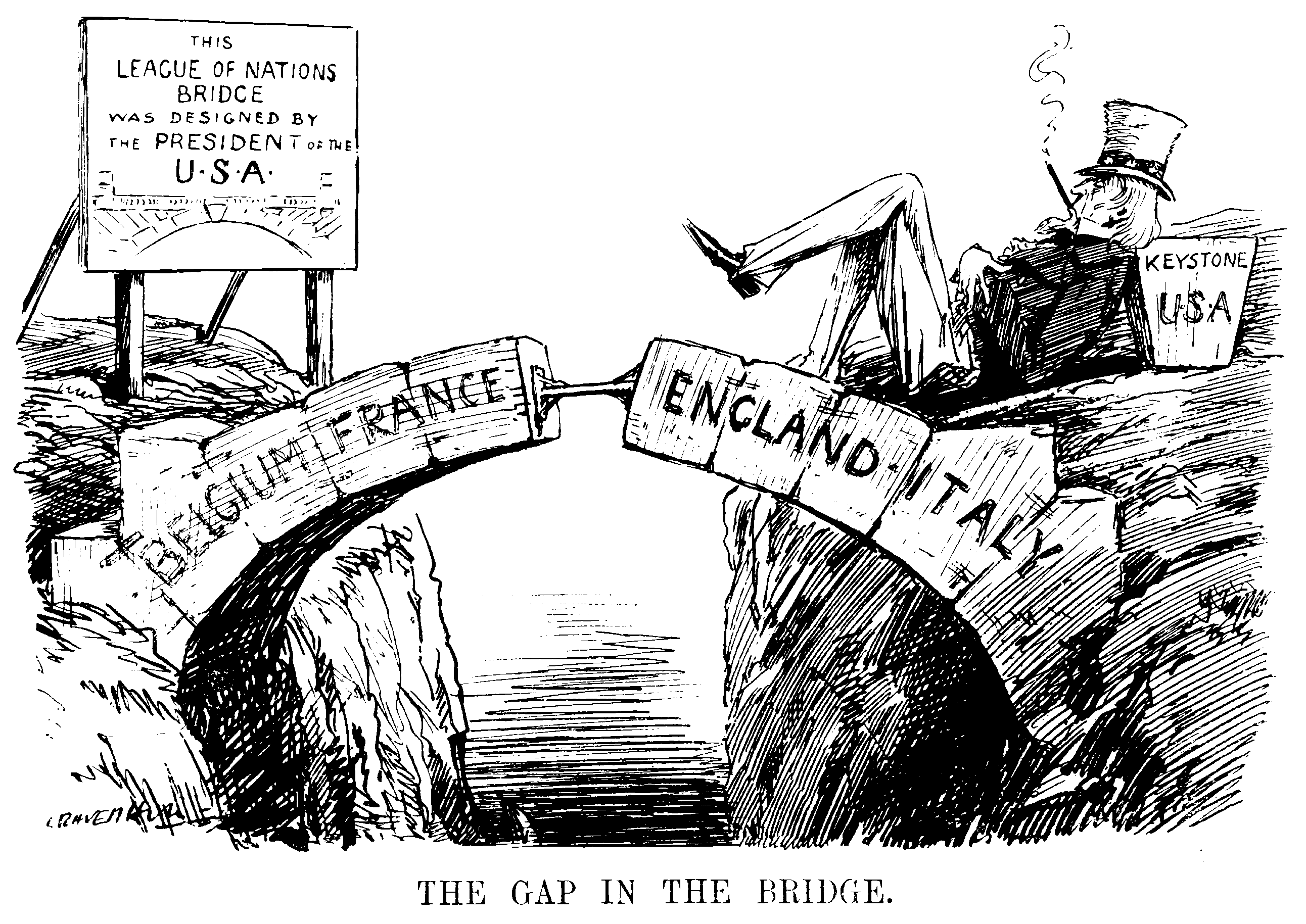

Despite said dismissiveness, President Wilson continued to promote his vision of the postwar world. The United States entered the fray, and Wilson proclaimed, “to make the world safe for democracy.” At the center of the plan was a new international organization, the League of Nations. This promise of collective security, that an attack on one sovereign member would be viewed as an attack on all, was a key component of the Fourteen Points. Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech was translated into many languages, and was even sent to Germany to encourage negotiation.

Yet, while President Wilson was celebrated in Europe as a “God of Peace,” many of his fellow statesmen were less enthusiastic about his plans for postwar Europe. America’s closest allies had little interest in the League of Nations. Allied leaders focused instead on guaranteeing the future safety of their own nations; refusing to sacrifice further. Negotiations made it clear that British prime minister David Lloyd-George was more interested in preserving Britain’s imperial domain, while French prime minister Clemenceau wanted severe financial reparations and limits on Germany’s future ability to wage war. The fight for a League of Nations was therefore largely on the shoulders of President Wilson.

Despite the Allies’ lack of agreement with the Fourteen Points, the key role of U.S. troops and U.S. dollars in the outcome gave the Americans an influential seat at the negotiating table at Versailles. Woodrow Wilson was seen as an international hero, and his appointee Thomas Lamont became a central figure in the negotiations that ended the war and set guidelines for German reparations that ultimately bankrupted the nation and led to World War II. Wilson’s Fourteen Points have received more attention from historians, but Britain and France were successful getting the punitive items they wanted into the final treaty. Lamont went along because shifting the financial burden to Germany guaranteed that the Allied nations that owed J.P. Morgan and Company so much money would be able to pay it back.

By June 1920, the final version of the treaty was signed and President Wilson was able to return home. The treaty was a compromise that included demands for German reparations, provisions for the League of Nations, and the promise of collective security. Wilson did not get everything he wanted, but Lamont did. According to historian Ferdinand Lundberg, the “total wartime expenditure of the United States government from April 6, 1917, to October 31, 1919, when the last contingent of troops returned from Europe, was $35,413,000,000. Net corporation profits for the period January 1, 1916, to July, 1921, when wartime industrial activity was finally liquidated, were $38,000,000,000.” In the years after the war, J.P. Morgan and Company would earn additional millions loaning Germany the money the treaty required it to pay to the allies so they could pay the bankers.

War’s Aftermath

The disposition of the Middle East was complicated by the increasing importance of its oil resources. Oil had been discovered in Iran in 1908, and during the period when petroleum was becoming the most important commodity of the twentieth century it was also becoming clear that some of the world’s largest reserves were located in the Middle East. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now known as BP) was established in 1908 to control production in Iran. After the war, British-controlled businesses that had been licensed by the Ottomans to develop oil discovered in Mesopotamia spurred British interest in creating the new Kingdom of Iraq under British mandate in 1920. The British-controlled multinational, TPC (Turkish Petroleum Company, established in 1912), received a 75-year concession to develop Iraq’s oil.

However, in 1933 when enormous deposits of oil were discovered in eastern Arabia, Ibn Saud turned to the Americans rather than the British to exploit these oil deposits, fearing renewed British meddling in his country. U.S. oil companies have been there ever since.

The movement to establish a Jewish Homeland—Zionism—was begun in the 1890s by Jewish Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl. Shocked by how Jews were being persecuted throughout Europe, even in liberal France, Herzl concluded that Jews would never be fully accepted as citizens anywhere and that they needed to establish a separate Jewish homeland. After some debate, his movement decided to begin buying land in Palestine, the site of the ancient Hebrew kingdom. Originally, most Jews around the world, especially more religious Jews, rejected the movement because they believed that Jews were not to return to Israel until the Messiah came. Zionists in Palestine often had problems with their Arab neighbors, who looked upon these new arrivals as Europeans trying to take over their country.

In the heat of the war, in 1917, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour promised that Palestine would be recognized as a “Jewish homeland,” in an attempt to gain support of Jews among the belligerents—not realizing that Zionism was hardly the majority view at that time within Judaism. Of course, the British also promised to respect Arab sovereignty in Palestine; setting the stage for conflict in the region that has continued to today.

Prohibition

The desire to rid the United States of what the majority perceived as evil is also seen in the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in the U.S. Liquor had ruined many American families, and women in particular had suffered as abused spouses. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union and similar prohibitionist organizations were prominent in the Progressive movement, pushing for a federal graduated income tax to replace the lucrative tax on liquor. The war made prohibition even more patriotic, since the beer industry was dominated by immigrant Germans, and the amendment was ratified shortly after the end of the war.

Knowledge Check:

Technological innovations and advancements along with revolutionary ideologies and chaos did not beget peace. The times discussed in chapters past came to a head here in The Great War and as we know (and will see) the Great War becomes World War I. How was the muddy and bumpy ride?

- And So It Begins…

- What were the main causes of the world war? Was it inevitable?

- Did the tangled relationships of European rulers contribute to stability or instability?

- Declaration of War

- Why did Europeans on the western front become trapped in the trenches for four years?

- Imagine being ordered “over the top” in a charge against the enemy trench. How would you react?

- The Technology of War

- How did new technologies change the way war is fought?

- Why did the Gallipoli invasion almost destroy Winston Churchill’s political career?

- What motivated the Armenian genocide?

- The US Joins The War

- Why did many Americans wish to stay out of the war?

- Why did other Americans want the war to last as long as possible?

- Mexico, Russia & The US

- How did the Russian Revolution relate to the United States’ entry into the war?

- Why did the U.S. support the tsarist “White Russian” counterrevolution?

- Support for The War

- What did it take for the American people to support US entry into the war?

- How did the ongoing Russian Revolution and the growing prominence of the Bolsheviks influence U.S. government policy?

- The Effects of War & “The Spanish Flu”

- What effects do you think the trenches and poison gas attacks had on European soldiers and civilians?

- Why did Germany throw so much into the Spring Offensive?

- Compare the “Spanish Flu” with the current COVID-19 pandemic. What can we learn from the past?

- Talks of Peace?

- Do you see any difficulty with the idea that Woodrow Wilson is typically seen by historians as an idealist, but his chief negotiator at Versailles was Thomas Lamont?

- Were Europeans right or wrong to put their national concerns first?

- In your opinion, what was the point of the League of Nations? As Wilson had imagined it, who did it benefit?

- Was the United States right or wrong to stay out of the League?

- War’s Aftermath

- How did the negotiations between European powers set the scene for the conflicts of the following century?

- What did the extension of racial conflict into the North after the war suggest about American attitudes regarding race?

- Was the anxiety of the Red Scare justified? Why were Americans so afraid of communism in the early 1920s?

This is an adaptation from Modern World History (on Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project) by Dan Allosso and Tom Williford, and is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- Periscope_rifle_Gallipoli_1915 © Ernest Brooks is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 2880px-Map_Europe_alliances_1914-en.svg © historicair is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Balkan_troubles1 © Leonard Raven-Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- DC-1914-27-d-Sarajevo-cropped © Achille Beltrame is licensed under a Public Domain license

- German_soldiers_in_a_railroad_car_on_the_way_to_the_front_during_early_World_War_I,_taken_in_1914._Taken_from_greatwar.nl_site © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FirstSerbianArmedPlane1915 © Museum of Yugoslav Aviation is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Battle_of_Tsingtao_Japanese_Landing © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Indian_bicycle_troops_Somme_1916_IWM_Q_3983 © John Warwick Brooke is licensed under a Public Domain license

- J.P._Morgan_and_J.P._Morgan_Jr © Moody's Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pacifists_at_Capitol_LOC_16992358889 © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pancho_and_his_followers

- Debs_Canton_1918_large © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Uncle_sam_propaganda_in_ww1 © James Montgomery Flagg is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Woodrow_Wilson_returning_from_the_Versailles_Peace_Conference_(1919) © Associated Press is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The_Gap_in_the_Bridge © Leonard Raven-Hill is licensed under a Public Domain license

- ThomasWLamont-1929Timemagazine © Unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- PikiWiki_Israel_7188_Herzl_on_board_reaching_the_shores_of_Palestine © אין מידע is licensed under a Public Domain license