29 4.1. What Is Consciousness?

Consciousness describes our awareness of our internal states and external stimuli. Internal states include feeling pain, hunger, thirst, sleepiness, thoughts, and emotions. External stimuli include the light from the sun, the warmth of a room, and the voice of a friend.

We experience different states of consciousness and different levels of awareness on a regular basis. We can describe consciousness as a continuum that ranges from full awareness to a deep sleep or coma. Sleep is a state marked by relatively low levels of physical activity and reduced sensory awareness that is distinct from periods of rest that occur during wakefulness. Wakefulness is characterized by high levels of sensory awareness, thought, and behavior. Beyond being awake or asleep, there are many other states of consciousness people experience. These include daydreaming, intoxication, and unconsciousness due to anesthesia. Often, we are not completely aware of our surroundings, even when we are fully awake. For instance, have you ever daydreamed while walking home from work or school without really thinking about the walk itself? You were capable of finding your way even though you were not aware of doing so. Many of these processes, like much of psychological behavior, are rooted in our biology.

Biological Rhythms

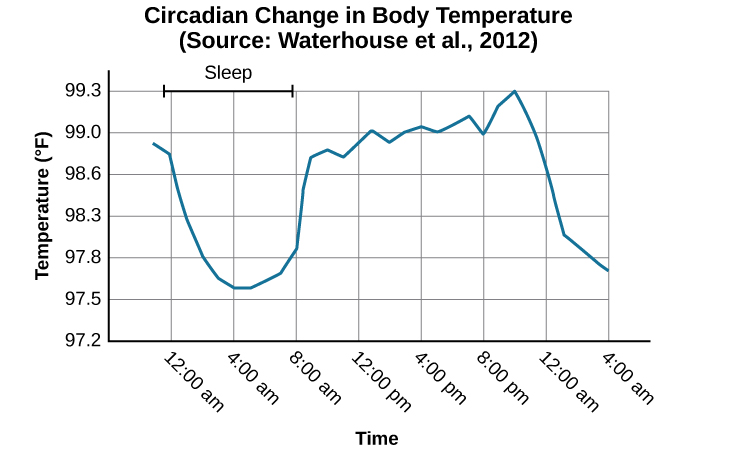

Biological rhythms are internal rhythms of biological activity. A woman’s menstrual cycle is one example of a biological rhythm—a recurring, cyclical pattern of bodily changes. One complete menstrual cycle takes about 28 days—a lunar month—but many biological cycles are much shorter. For example, body temperature fluctuates cyclically over a 24-hour period (Figure 4.2). Alertness is associated with higher body temperatures, and sleepiness with lower body temperatures.

This pattern of temperature fluctuation, which repeats every day, is one example of a circadian rhythm. A circadian rhythm is a biological rhythm that takes place over a period of about 24 hours. Our sleep-wake cycle, which is linked to our environment’s natural light-dark cycle, is perhaps the most obvious example of a circadian rhythm, but we also have daily fluctuations in heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, and body temperature. Some circadian rhythms play a role in changes in our state of consciousness.

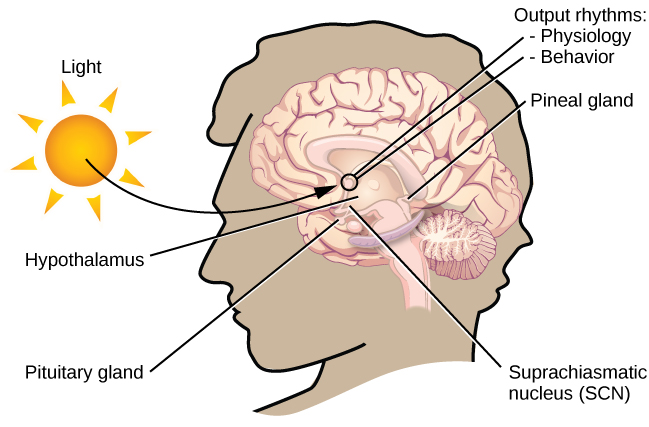

Biological rhythms are controlled by an internal clock in the brain. As shown in Figure 4.3. the brain’s clock mechanism is located in an area of the hypothalamus known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The axons of light-sensitive neurons in the retina provide information to the SCN based on the amount of light present, allowing this internal clock to be synchronized with the outside world (Klein et al., 1991; Welsh et al., 2010).

Problems With Circadian Rhythms

Generally, and for most people, our circadian cycles are aligned with the outside world. For example, most people sleep during the night and are awake during the day. One important regulator of sleep-wake cycles is the hormone melatonin, which is released by the pineal gland. Melatonin is thought to be involved in the regulation of various other biological rhythms and has been linked to effective immune function (Hardeland et al., 2006). Melatonin release is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light.

There are considerable individual differences in our sleep-wake cycles. For instance, some people would say they are morning people, while others would consider themselves to be night owls. These individual differences in circadian patterns of activity are known as a person’s chronotype, and research demonstrates that morning larks and night owls differ with regard to sleep regulation (Taillard et al., 2003). Sleep regulation refers to the brain’s control of switching between sleep and wakefulness, as well as coordinating this cycle with the outside world.

Link to Learning

Watch this brief video about circadian rhythms and how they affect sleep to learn more.

Link to learning

Spend 5-10 minutes taking this online assessment to find out whether you are an Owl or a Lark

Disruptions of Normal Sleep

Whether lark, owl, or somewhere in between, there are situations in which a person’s circadian clock gets out of synchrony with the external environment. One way that this happens involves traveling across multiple time zones. When we do this, we often experience jet lag. Jet lag is a collection of symptoms that results from the mismatch between our internal circadian cycles and our environment. These symptoms include fatigue, sluggishness, irritability, and insomnia, i.e., a consistent difficulty in falling or staying asleep for at least three nights a week over the period of a month (Roth, 2007).

Individuals who do rotating shift work are also likely to experience disruptions in circadian cycles. Rotating shift work refers to a work schedule that changes from early to late on a daily or weekly basis. For example, a person may work from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Monday, 3:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, and 11:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday. In such instances, the individual’s schedule changes so frequently that it becomes difficult for a normal circadian rhythm to be maintained. This often results in sleeping problems, and it can lead to signs of depression and anxiety. These kinds of schedules are common for individuals working in health care professions and service industries, and they are often associated with persistent feelings of exhaustion and agitation that can make someone more prone to making mistakes on the job (Gold et al., 1992; Presser, 1995).

Rotating shift work has pervasive effects on the lives and experiences of individuals engaged in that kind of work, which is clearly illustrated in stories reported in a qualitative study that researched the experiences of middle-aged nurses who worked rotating shifts (West et al., 2009). Several of the nurses interviewed commented that their work schedules affected their relationships with their family. One of the nurses said,

“If you’ve had a partner who does work regular job 9 to 5 office hours . . . the ability to spend time, good time with them when you’re not feeling absolutely exhausted . . . that would be one of the problems that I’ve encountered.” (West et al., 2009, p. 114)

While disruptions in circadian rhythms can have negative consequences, there are things we can do to help us realign our biological clocks with the external environment. Some of these approaches, such as using a bright light as shown in Figure 4.4, have been shown to alleviate some of the problems experienced by individuals suffering from jet lag or from the consequences of rotating shift work. Because the biological clock is driven by light, exposure to bright light during working shifts and dark exposure when not working, can help combat insomnia and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Huang et al., 2013).

Link to Learning

Watch this video about overcoming jet lag to learn some tips.

Insufficient Sleep

When people have difficulty getting enough sleep due to their work or the demands of day-to-day life, they accumulate a sleep debt. A person with a sleep debt does not get sufficient sleep on a chronic basis. The consequences of sleep debt include decreased levels of alertness and mental efficiency. Interestingly, since the advent of electric light, the amount of sleep that people get has declined. While we certainly welcome the convenience of having artificial lighting in our lives, we also suffer the consequences of reduced amounts of sleep because we are more active during the nighttime hours than our ancestors were. As a result, many of us sleep less than 7–8 hours a night and accrue a sleep debt. There is tremendous variation in any given individual’s sleep needs. The amount of sleep we need varies across the lifespan. The National Sleep Foundation (n.d.) cites research estimating that newborns require the most sleep (between 12 and 18 hours a day) but this amount declines to just 7–9 hours by the time we are adults. A meta-analysis, which is a study that combines the results of many related studies, indicates that by the time we are 65 years old, we average fewer than 7 hours of sleep per day (Ohayon et al., 2004).

If you lie down to take a nap and fall asleep very easily, you may have sleep debt. Given that college students are notorious for suffering from significant sleep debt (Hicks et al., 1992; 2001; Miller et al., 2010), it is likely that you and your classmates deal with sleep debt-related issues on a regular basis. In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation updated their sleep duration hours, to better accommodate individual differences. Table 4.1 shows the new recommendations, which describes sleep durations which vary from “recommended” and “may be appropriate”, to “not recommended”.

Table 4.1. Sleep Needs at Different Ages

|

AGE |

RECOMMENDED |

MAY BE APPROPRIATE |

NOT RECOMMENDED |

|---|---|---|---|

|

0–3 months |

14–17 hours |

11–13 hours |

Fewer than 11 hours |

|

4–11 months |

12–15 hours |

10–11 hours |

Fewer than 10 hours |

|

1–2 years |

11–14 hours |

9–10 hours |

Fewer than 9 hours |

|

3–5 years |

10–13 hours |

8–9 hours |

Fewer than 8 hours |

|

6–13 years |

9–11 hours |

7–8 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours |

|

14–17 years |

8–10 hours |

7 hours |

Fewer than 7 hours |

|

18–25 years |

7–9 hours |

6 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours |

|

26–64 years |

7–9 hours |

6 hours |

Fewer than 6 hours |

|

≥65 years |

7–8 hours |

5–6 hours |

Fewer than 5 hours |

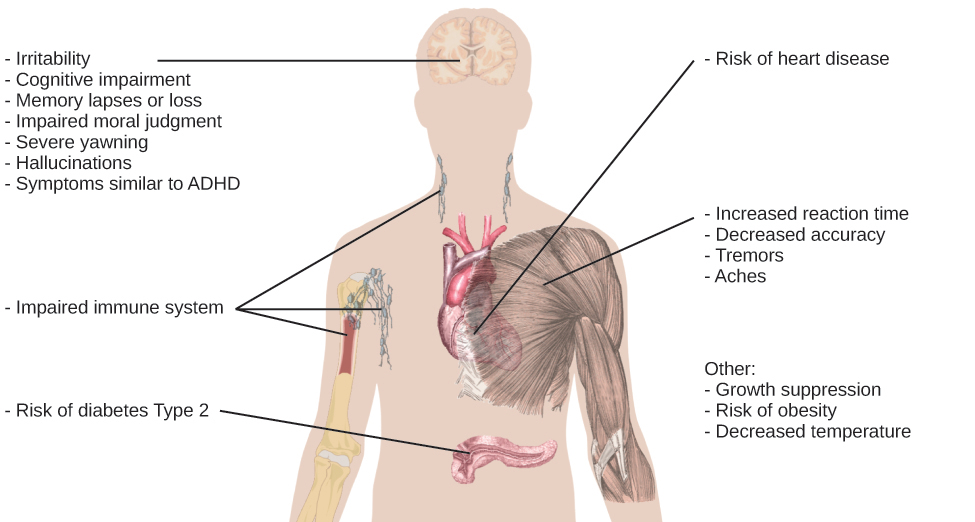

Sleep deprivation can have significant effects on the body, cognition, and health (see Figure 4.5). As mentioned earlier, lack of sleep can result in decreased mental alertness and impaired cognitive function. In addition, sleep deprivation often results in depression-like symptoms. These effects can occur as a function of accumulated sleep debt or in response to more acute periods of sleep deprivation. It may surprise you to know that sleep deprivation is associated with chronic disease including diabetes, obesity, increased blood pressure, heart disease, increased levels of stress hormones, and reduced immune functioning (Banks & Dinges, 2007; Center for Disease Control, 2022a). Studies have shown that having less than the optimal amount of sleep reduces antibody production after a vaccination. So, being sleep-deprived can reduce the efficacy of vaccinations (Stickgold, 2015).

The Center for Disease Control estimates that over one-third of adults (35%) in the United States do not get enough sleep (defined as less than seven hours per day). Short sleep duration is slightly more common among males (33.4%) than females (32.2%) and is most common among people in the 25 to 44-year-old age group (36.4%). There is considerable racial variation among who is most likely to be sleep deprived. Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders (47%) and African-American and non-Hispanic Blacks (43.5%) are the two groups with the highest proportion of people with short sleep duration. In contrast, non-Hispanic Whites (30.2%)and Asians (30.5%) have the lowest percentage of people who sleep less than seven hours per day (Center for Disease Control, 2022b).

A sleep deprived individual generally will fall asleep more quickly than if they were not sleep deprived. Some sleep-deprived individuals have difficulty staying awake when they stop moving (for example, when sitting and watching television or driving a car). That is why individuals suffering from sleep deprivation can put themselves and others at risk when they drive a car or work with dangerous machinery. Some research suggests that sleep deprivation affects cognitive and motor function as much as alcohol intoxication (Williamson & Feyer, 2000). Research shows that if a person stays awake for more than 24 hours (Killgore & Weber, 2014; Killgore et al., 2007), or has repeated nights with fewer than four hours in bed (Wickens et al., 2015), they are likely to experience symptoms of extreme sleep deprivation, including irritability, distractibility, and impairments in cognitive and moral judgment. If someone stays awake for 48 hours in a row, they could start to hallucinate.

Links to Learning

Read this article about sleep needs to assess your own sleeping habits.

Use the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess whether you are sleep deprived

Visit this CDC website to learn more about national and state trends in sleep debt and its health consequences in adults.

Watch this video interview of Tricia Hersey (the Nap Bishop) who advocates for rest as a form of resistance against capitalism and white supremacy, which perpetuates the culture of working all the time.