14 Contexts of Development

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 14, you should be equipped to:

- Discuss how the concept of family has changed over time and describe the different types of family units.

- Understand the short and long-term consequences of divorce.

- Identify different parenting styles and their potential effects on children.

- Understand the different ways that media may influence developmental outcomes.

- Explain the effects of stress on children’s development and discuss why resiliency is so important for well-being.

- Identify and describe the different types of physical and mental illnesses.

- Be familiar with the different circumstances that threaten children’s well-being.

Family

What is family?

In J.K. Rowling's famous Harry Potter novels, the boy magician lives in a cupboard under the stairs. His unfortunate situation is the result of his wizarding parents having been killed in a duel, causing the young Potter to be subsequently shipped off to live with his cruel aunt and uncle. Although the family may not be the central theme of these wand and sorcery novels, Harry's example raises a compelling question: what, exactly, counts as family?

The definition of family changes across time and across cultures. A traditional family has been defined as two or more people who are related by blood, marriage, or adoption (Murdock, 1949). Historically, the most standard version of the traditional family has been the two-parent family. Are there people in your life you consider family who are not necessarily related to you in the traditional sense? Harry Potter would undoubtedly call his schoolmates Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger family, even though they do not fit the traditional definition. Likewise, Harry might consider Hedwig, his snowy owl, a family member, and he would not be alone in doing so. Research from the US (Harris, 2015) and Japan (Veldkamp, 2009) finds that many pet owners consider their pets to be members of the family. Another traditional form of family is the joint family, in which three or more generations of blood relatives live in a single household or compound. Joint families often include cousins, aunts, uncles, and other relatives from the extended family. Versions of the joint family system exist around the globe including in South Asia, Southern Europe, the South Pacific, and other locations.

In more modern times, the traditional definition of family has been criticized as being too narrow. Modern families—especially those in industrialized societies—exist in many forms, including the single-parent family, foster families, same-sex couples, childfree families, and many other variations from traditional norms. Common to each of these family forms is commitment, caring, and close emotional ties—which are increasingly the defining characteristics of family (Benokraitis, 2015). The changing definition of family has come about, in part, because of factors such as divorce and re-marriage. In many cases, people do not grow up with their family of orientation but become part of a stepfamily or blended family. Whether a single-parent, joint, or two-parent family, a person’s family of orientation or the family into which he or she is born, generally acts as the social context for young children learning about relationships.

According to Bowen (1978), each person has a role to play in his or her family, and each role comes with certain rules and expectations. This system of rules and roles is known as family systems theory. The goal for the family is stability: rules and expectations that work for all. The family rules and expectations change when the role of one family member changes. Such changes ripple through the family and cause each member to adjust his or her own role and expectations to compensate for the change.

Gender has been one factor by which family roles have long been assigned. Traditional roles have historically placed housekeeping and childrearing squarely in the realm of women’s responsibilities. Men, by contrast, have been seen as protectors and as providers of resources including money. Increasingly, families are crossing these traditional roles with women working outside the home and men contributing more to domestic and childrearing responsibilities. Despite this shift toward more egalitarian roles, women still tend to do more housekeeping and childrearing tasks than their husbands (known as the second shift) (Hochschild & Machung, 2012).

[Interestingly, parental roles have an impact on the ambitions of their children. Croft and her colleagues (2014) examined the beliefs of more than 300 children. The researchers discovered that when fathers endorsed more equal sharing of household duties and when mothers were more workplace oriented it influenced how their daughters thought. In both cases, daughters were more likely to have ambitions toward working outside the home and working in less gender-stereotyped professions. [1]

Family Atmosphere

One of the ways to assess the quality of family life is to consider the tasks of families. Berger (2005) lists five family functions:

- Providing food, clothing, and shelter

- Encouraging learning

- Developing self-esteem

- Nurturing friendships with peers

- Providing harmony and stability

There are five functions of the family environment. [2]

Notice that in addition to providing food, shelter, and clothing, families are responsible for helping the child learn, relate to others, and have a confident sense of self. The family provides a harmonious and stable environment for living. A good home environment is one in which the child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs are adequately met. Sometimes families emphasize physical needs but ignore cognitive or emotional needs. Other times, families pay close attention to physical needs and academic requirements but may fail to nurture the child’s friendships with peers or guide the child toward developing healthy relationships. Parents might want to consider how it feels to live in the household. Is it stressful and conflict-ridden? Is it a place where family members enjoy being?

The Family Stress Model

Family relationships are significantly affected by conditions outside the home. For instance, the Family Stress Model describes how financial difficulties are associated with parents’ depressed moods, which in turn lead to marital problems and poor parenting that contributes to poorer child adjustment (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Within the home, parental marital difficulty or divorce affects more than half the children growing up today in the United States. Divorce is typically associated with economic stresses for children and parents, the renegotiation of parent-child relationships (with one parent typically as primary custodian and the other assuming a visiting relationship), and many other significant adjustments for children. Divorce is often regarded by children as a sad turning point in their lives, although for most it is not associated with long-term problems of adjustment (Emery, 1999).

Family Forms

The sociology of the family examines the family as an institution and a unit of socialization. Sociological studies of the family look at demographic characteristics of the family members: family size, age, ethnicity and gender of its members, social class of the family, the economic level and mobility of the family, professions of its members, and the education levels of the family members.

Currently, one of the biggest issues that sociologists study is the changing roles of family members. Often, each member is restricted by the gender roles of the traditional family. These roles, such as the father as the breadwinner and the mother as the homemaker, are declining. Now, the mother is often the supplementary provider while retaining the responsibilities of child-rearing. In this scenario, females' role in the labor force is "compatible with the demands of the traditional family.” Sociology studies have examined the adaptation of males' roles as caregivers as well as providers. The gender roles are becoming increasingly interwoven and various other family forms are becoming more common.

Families Without Children

Families do not always include children. [3]

Singlehood families contains a person who is not married or in a common-law relationship. He or she may share a relationship with a partner but lead a single lifestyle. Couples that are childless are often overlooked in the discussion of families.

Families with One Parent

A family in which one parent has the majority of day-to-day responsibilities for raising their child or children. [4]

A single-parent family usually refers to a parent who has most of the day-to-day responsibilities in the raising of the child or children, who is not living with a spouse or partner, or who is not married. The dominant caregiver is the parent with whom the children reside for the majority of the time; if the parents are separated or divorced, children live with their custodial parent and have visitation with their noncustodial parent. In western society in general, following a separation a child will end up with the primary caregiver, usually the mother, and a secondary caregiver, usually the father. Single parent by choice families refers to a family that a single person builds by choice. These families can be built with the use of assisted reproductive technology and donor gametes (sperm and/or egg) or embryos, surrogacy, foster or kinship care, and adoption.

Two-Parent Families

While the traditional family structure is common in the U.S., it is not the most common type of family worldwide.[5]

The nuclear family is often referred to as the traditional family structure. It includes two married parents and children. While common in industrialized cultures (such as the U.S.), it is not actually the most common type of family worldwide Cohabitation is an arrangement where two people, who are not married, live together in an intimate relationship, particularly an emotionally and/or sexually intimate one, on a long-term or permanent basis. Today, cohabitation is a common pattern among people in the Western world. More than two-thirds of married couples in the U.S. say that they lived together before getting married.

Gay and lesbian couples with children have same-sex families. While now recognized legally in the United States, discrimination against same-sex families is not uncommon. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, there is “ample evidence to show that children raised by same-gender parents fare as well as those raised by heterosexual parents. More than 25 years of research have documented that there is no relationship between parents' sexual orientation and any measure of a child's emotional, psychosocial, and behavioral adjustment. Conscientious and nurturing adults, whether they are men or women, heterosexual or homosexual, can be excellent parents. The rights, benefits, and protections of civil marriage can further strengthen these families.”

A blended family describes families with mixed parents: one or both parents remarried, bringing children of the former family into the new family31. Blended families are complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful stepfamily relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985). These families are also referred to as stepfamilies.

Families That Include Additional Adults

Extended families are most common worldwide. [6]

An extended family includes three generations, grandparents, parents, and children. This is the most common type of family worldwide.

Families by choice are relatively newly recognized. It was popularized by the LGBTQ community to describe a family not recognized by the legal system. It may include adopted children, live-in partners, kin of each member of the household, and close friends. Increasingly family by choice is being practiced by those who see the benefit of including people beyond blood relatives in their families. While most families in the U.S. are monogamous, some families have more than two married parents. These families are polygamous. Polygamy is illegal in all 50 states, but it is legal in other parts of the world.

Kinship families are those in which the full-time care, nurturing, and protection of a child is provided by relatives, members of their tribe or clan, godparents, stepparents, or other adults who have a family relationship with a child. When children cannot be cared for by their parents, research finds benefits to kinship care.

When a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents this creates adoptive families. Legal adoption permanently transfers all rights and responsibilities and is intended to affect a permanent change in status and as such requires societal recognition, either through legal or religious sanction. Adoption can be done privately, through an agency, or through foster care in the U.S. or from abroad. Adoptions can be closed (no contact with birth/biological families or open, with different degrees of contact with birth/biological families). Couples, both opposite and same-sex, and single parents can adopt (although not all agencies and foreign countries will work with unmarried, single, or same-sex intended parents).

When parents are not of the same ethnicity, they build interracial families. Until the decision in Loving v Virginia in 1969, this was not legal in the U.S. There are other parts of the world where marrying someone outside of your race (or social class) has legal and social ramifications. These families may experience issues unique to each individual family’s culture.

Changes in Families

The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types—not just intact, two-parent households. Harmony and stability can be achieved in many family forms and when it is disrupted, either through a divorce, efforts to blend families, or any other circumstances, the child suffers (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Changes continue to happen, but for children, they are especially vulnerable. Divorce and how it impacts children depends on how the caregivers handle the divorce as well as how they support the emotional needs of the child.

Divorce

A lot of attention has been given to the impact of divorce on the life of children. The assumption has been that divorce has a strong, negative impact on the child and that single-parent families are deficient in some way. However, 75-80 percent of children and adults who experience divorce suffer no long-term effects (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). An objective view of divorce, re-partnering, and remarriage indicate that divorce, remarriage, and life in stepfamilies can have a variety of effects.

Factors Affecting the Impact of Divorce

As you look at the consequences (both pro and con) of divorce and remarriage on children, keep these family functions in mind. Some negative consequences are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Drexler, 2005). Some positive consequences reflect improvements in meeting these functions. For instance, we have learned that positive self-esteem comes in part from a belief in the self and one’s abilities rather than merely being complemented by others. In single-parent homes, children may be given more opportunities to discover their own abilities and gain independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce leads to fighting between the parents, and the child is included in these arguments, their self-esteem may suffer.

The impact of divorce on children depends on a number of factors. The degree of conflict prior to the divorce plays a role. If the divorce means a reduction in tensions, the child may feel relief. If the parents have kept their conflicts hidden, the announcement of a divorce can come as a shock and be met with enormous resentment. Another factor that has a great impact on the child concerns financial hardships they may suffer, especially if financial support is inadequate. Another difficult situation for children of divorce is the position they are put into if the parents continue to argue and fight—especially if they bring the children into those arguments.

Short-term consequences: In roughly the first year following divorce, children may exhibit some of these short-term effects:

- Grief over losses suffered. The child will grieve the loss of the parent they no longer see as frequently. The child may also grieve about other family members that are no longer available. Grief sometimes comes in the form of sadness but it can also be experienced as anger or withdrawal. Older children may feel depressed.

- Reduced Standard of Living. Very often, divorce means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing, or other items to which they’ve grown accustomed. Or it may mean that there is less eating out or being able to afford cable television, and so on. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages, and other expenditures. Furthermore, stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children.

- Adjusting to Transitions. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Long-Term consequences: Here are some effects that go beyond just the first year following a divorce.

- Economic/Occupational Status. One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education or occupational status. This may be a consequence of lower income and fewer resources for funding education, rather than the divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on economic status (Drexler, 2005).

- Improved Relationships with the Custodial Parent (usually the mother): Most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop stronger, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Steward, Copeland, Chester, Malley, and Barenbaum, 1997).

- Greater emotional independence in sons. Drexler (2005) notes that sons who are raised by mothers only develop an emotional sensitivity to others that is beneficial in relationships.

- Feeling more anxious in their own love relationships. Children of divorce may feel more anxious about their own relationships as adults. This may reflect a fear of divorce if things go wrong, or it may be a result of setting higher expectations for their own relationships.

- Adjustment of the custodial parent. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts to the divorce. If that parent is adjusting well, the children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce.[7]

Socialization

Parenting Styles

Developmental psychologists have been interested in how parents influence the development of children's social and instrumental competence since at least the 1920s. One of the most robust approaches to this area is the study of what has been called "parenting style." We will explore four types of parenting styles and then discuss the consequences of the different styles for children.

Parenting is a complex activity that includes many specific behaviors that work individually and together to influence child outcomes. Although specific parenting behaviors, such as spanking or reading aloud, may influence child development, looking at any specific behavior in isolation may be misleading. Many writers have noted that specific parenting practices are less important in predicting child well-being than in the broad pattern of parenting. Most researchers who attempt to describe this broad parental milieu rely on Diana Baumrind's concept of parenting style. The construct of parenting style is used to capture normal variations in parents' attempts to control and socialize their children (Baumrind, 1991). Two points are critical in understanding this definition. First, parenting style is meant to describe normal variations in parenting. In other words, the parenting style typology Baumrind developed should not be understood to include deviant parenting, such as might be observed in abusive or neglectful homes. Second, Baumrind assumes that normal parenting revolves around issues of control. Although parents may differ in how they try to control or socialize their children and the extent to which they do so, it is assumed that the primary role of all parents is to influence, teach, and control their children.

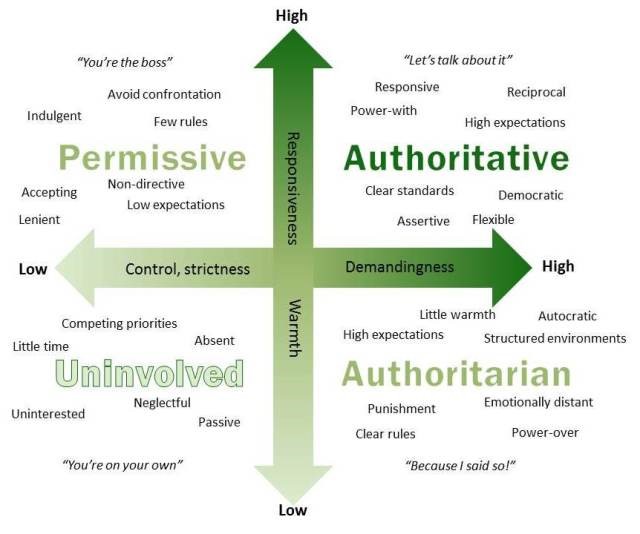

Parenting style captures two important elements of parenting: parental responsiveness and parental demandingness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Parental responsiveness (also referred to as parental warmth or supportiveness) refers to "the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation, and self-assertion by being attuned, supportive, and acquiescent to children's special needs and demands" (Baumrind, 1991, p. 62). Parental demandingness (also referred to as behavioral control) refers to "the claims parents make on children to become integrated into the family whole, by their maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys" (Baumrind, 1991, pp. 61- 62).

Baumrind’s Four Parenting Styles in Depth

Categorizing parents according to whether they are high or low on parental demandingness and responsiveness creates a typology of four parenting styles: indulgent, authoritarian, authoritative, and uninvolved (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Each of these parenting styles reflects different naturally occurring patterns of parental values, practices, and behaviors (Baumrind, 1991) and a distinct balance of responsiveness and demandingness.

Baumrind's Four Types of Parenting Styles[8]

The four types of parenting styles [9]

Indulgent parents (also referred to as "permissive" or "nondirective") are more responsive than they are demanding. They are nontraditional and lenient, do not require mature behavior, allow considerable self-regulation, and avoid confrontation" (Baumrind, 1991, p. 62). Indulgent parents may be further divided into two types: democratic parents, who, though lenient, are more conscientious, engaged, and committed to the child, and nondirective parents. Authoritarian parents are highly demanding and directive, but not responsive. "They are obedience- and status-oriented, and expect their orders to be obeyed without explanation" (Baumrind, 1991, p. 62). These parents provide well-ordered and structured environments with clearly stated rules. Authoritarian parents can be divided into two types: nonauthoritarian-directive, who are directive, but not intrusive or autocratic in their use of power, and authoritarian-directive, who are highly intrusive. Authoritative parents are both demanding and responsive. "They monitor and impart clear standards for their children's conduct. They are assertive, but not intrusive and restrictive. Their disciplinary methods are supportive, rather than punitive. They want their children to be assertive, as well as socially responsible and self-regulated, as well as cooperative" (Baumrind, 1991, p. 62). Uninvolved parents are low in both responsiveness and demandingness. In extreme cases, this parenting style might encompass both rejecting-neglecting and neglectful parents, although most parents of this type fall within the normal range. Because parenting style is a typology, rather than a linear combination of responsiveness and demandingness, each parenting style is more than and different from the sum of its parts (Baumrind, 1991). In addition to differing in responsiveness and demandingness, the parenting styles also differ in the extent to which they are characterized by a third dimension: psychological control. Psychological control "refers to control attempts that intrude into the psychological and emotional development of the child" (Barber, 1996, p. 3296) through the use of parenting practices such as guilt induction, withdrawal of love, or shaming. One key difference between authoritarian and authoritative parenting is in the dimension of psychological control. Both authoritarian and authoritative parents place high demands on their children and expect their children to behave appropriately and obey parental rules. Authoritarian parents, however, also expect their children to accept their judgments, values, and goals without questioning. In contrast, authoritative parents are more open to give and take with their children and make greater use of explanations. Thus, although authoritative and authoritarian parents are equally high in behavioral control, authoritative parents tend to be low in psychological control, while authoritarian parents tend to be high.

Consequences for Children

Parenting style has been found to predict child well-being in the domains of social competence, academic performance, psychosocial development, and problem behavior. Research in the United States, based on parent interviews, child reports, and parent observations consistently finds:

- Children and adolescents whose parents are authoritative rate themselves and are rated by objective measures as more socially and instrumentally competent than those whose parents are nonauthoritative (Baumrind, 1991; Weiss & Schwarz, 1996; Miller et al., 1993).

- Children and adolescents whose parents are uninvolved perform most poorly in all domains.

- In general, parental responsiveness predicts social competence and psychosocial functioning, while parental demandingness is associated with instrumental competence and behavioral control (i.e., academic performance and deviance). These findings indicate:

- Children and adolescents from authoritarian families (high in demandingness, but low in responsiveness) tend to perform moderately well in school and be uninvolved in problem behavior, but they have poorer social skills, lower self-esteem, and higher levels of depression.

- Children and adolescents from indulgent homes (high in responsiveness, low in demandingness) are more likely to be involved in problem behavior and perform less well in school, but they have higher self-esteem, better social skills, and lower levels of depression.

In reviewing the literature on parenting style, one is struck by the consistency with which authoritative upbringing is associated with both instrumental and social competence and lower levels of problem behavior in both boys and girls at all developmental stages. The benefits of authoritative parenting and the detrimental effects of uninvolved parenting are evident as early as the preschool years and continue throughout adolescence and into early adulthood. Although specific differences can be found in the competence evidenced by each group, the largest differences are found between children whose parents are unengaged and their peers with more involved parents. [10]

Spanking

Spanking is often thought of as a rite of passage for children, and this method of discipline continues to be endorsed by the majority of parents (Smith, 2012). Just how effective is spanking, however, and are there any negative consequences? After reviewing the research, Smith (2012) states “many studies have shown that physical punishment, including spanking, hitting and other means of causing pain, can lead to increased aggression, antisocial behavior, physical injury and mental health problems for children” (p. 60). Gershoff, (2008) reviewed decades of research and recommended that parents and caregivers make every effort to avoid physical punishment and called for the banning of physical discipline in all U.S. schools.

In a longitudinal study that followed more than 1500 families from 20 U.S. cities, parents’ reports of spanking were assessed at ages three and five (MacKenzie, Nicklas, Waldfogel, & Brooks-Gunn, 2013). Measures of externalizing behavior and receptive vocabulary were assessed at age nine. Results indicated that those children who were spanked at least twice a week by their mothers scored 2.66 points higher on a measure of aggression and rule-breaking than those who were never spanked. Additionally, those who were spanked less still scored 1.17 points higher than those never spanked. When fathers did the spanking, those spanked at least two times per week scored 5.7 points lower on a vocabulary test than those never spanked. This study revealed the negative cognitive effects of spanking in addition to the increase in aggressive behavior.

Internationally, physical discipline is increasingly being viewed as a violation of children’s human rights. According to Save the Children (2019), 46 countries have banned the use of physical punishment, and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2014) called physical punishment “legalized violence against children” and advocated that physical punishment be eliminated in all settings. [11]

The use of positive reinforcement in changing behavior is almost always more effective than using punishment. This is because positive reinforcement makes the person feel better, helping create a positive relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. Examples of positive reinforcement that are effective in everyday life include verbal praise or approval, the awarding of the desired item, and money. Punishment, on the other hand, is more likely to create only temporary changes in behavior because it is based on coercion and typically creates a negative and adversarial relationship with the person providing the reinforcement. When the person who provides the punishment leaves the situation, the unwanted behavior is likely to return.[12]

Effective Discipline

Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward him/her for it. An example of this is shaping. Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behavior, in shaping, we reinforce successive approximations of a target behavior. Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the child must first display the behavior. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that the child will display anything but the simplest of behaviors spontaneously. In shaping, behaviors are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following:

- Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behavior.

- Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behavior. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response.

- Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behavior.

- Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior.

- Finally, only reinforce the desired behavior.

Let’s consider parents whose goal is to have their son learn to clean his room. They use shaping to help him master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each step. First, he cleans up one toy. Second, he cleans up five toys. Third, he chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put his books and clothes away. Fourth, he cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, he cleans his entire room. [13]

Other alternatives that are advocated by child development specialists include:

- Praising and modeling appropriate behavior

- Providing time-outs for inappropriate behavior

- Giving choices

- Helping the child identify emotions and learning to calm down

- Ignoring small annoyances (e.g., using extinction for an undesirable behavior that has been inadvertently reinforced, such as discontinuing attention when a child has a tantrum)

- Withdrawing privileges for undesirable behavior (e.g., a teenager loses car privilege for coming home intoxicated) [14]

Media

Influences on Development

Children view far more television today than in the 1960s; so much, in fact, that they have been referred to as Generation M (media). The amount of screen time varies by age. As of 2017, children 0-8 spend an average of 2 hours and 19 minutes. Children 8-12 years of age spend almost 6 hours a day on screen media. And 13- to 18-year-olds spend an average of just under hours a day in entertainment media use. [15] Over a year, that adds up to 114 full days watching a screen for fun. That’s just the time they spend in front of a screen for entertainment. It doesn’t include the time they spend on the computer at school for educational purposes or at home for homework. [16] Given that the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that children should limit media use to 1 to 2 hours per day, then what are the potential effects of all of this screen time? [17]

Cognitive Influences

In a longitudinal study by Katherine Hanson (2017) the impact of television exposure on 12-21 month-old infants on later cognitive and learning outcomes at age 6 to 9 years of age to assess whether parent-child interactions mediate this association. Infants in the video condition were assigned one of two videos that were designed to facilitate parent-infant interactions through co-viewing. Findings indicated that while parents used the video content to engage with their children, there was an overall reduction in the quality and quantity of parent-infant interactions when the TV was on.

At ages 6-9 years old, these same children were tested again on executive functioning, academic, and language assessments during the first half of the laboratory visit. The results indicate that parent-infant co-viewing has a direct negative association with children’s executive function skills, academic achievement, and language during middle childhood. In fact, the more children co-viewed with their parents during infancy, the more likely they were to exhibit poorer working memory, academic performance, and language skills during middle childhood. In fact, the more children co-viewed with their parents during infancy, the more likely they were to exhibit poorer working memory, academic performance, and language skills.

However, the quality of parent-child interactions or parent language in the presence of television did not moderate this relationship. This study suggests that the effects are not due to actually watching television per se. Rather, the time spent co-viewing during infancy replaces time spent with the parent outside of the television context.[18]

Physical Influences

Children and adolescents are inundated with media and can spend more than 6 hours each day watching television, YouTube, and movies; playing video games; listening to music, and surfing the internet. The use of television and other screen devices (e.g., smartphones, tablets, computers) is associated with the risk of obesity through a variety of mechanisms, including insufficient physical activity and increased calorie intake while using screen devices. [19]

Screen time increases children’s risk for obesity because sitting and watching a screen is time that is not spent being physically active. TV commercials and other screen ads can lead to unhealthy food choices. Most of the time, the foods in ads that are aimed at kids are high in sugar, salt, or fats. Children eat more when they are watching TV, especially if they see ads for food. [20]

Several studies have shown that increased media use is associated with shorter and poorer quality sleep, which is also a significant risk factor for obesity. After-school screen time is associated with the increased size of evening snack portions and overall poor diet quality in adolescents. Moreover, epidemiologic studies have reported that consuming most daily calories in the evening is associated with a higher body mass index (BMI) and an increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Taken together, long-term media use is associated with negative effects on a variety of adolescent health behaviors, including unhealthy eating at night and inadequate sleep. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate interventions that focus on decreasing adolescents’ media use to prevent overweight and obesity, and other related chronic health conditions. [21]

Strategies to decrease media use can include parents setting limits on media use. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that children watch no more than 1 to 2 hours of "quality programming" per day and that televisions be removed from children's bedrooms. [22] Parents are also encouraged to have their children exercise at least 60 minutes each day, as per CDC guidelines. [23]

Behavioral Influences

Studies have reported that young children who have two or more hours per day using mobile devices show more externalizing behaviors (aggression, tantrums) and inattention (Tamana, et al., 2019) and a higher risk of behavioral problems (Wu, 2017). What mechanism could be responsible for those behavioral outcomes? This was a question that Al Bandura sought to address. [24]

Albert Bandura (1977 developed social-learning theory which is learning by watching others. His theory calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through operant conditioning, as suggested by Skinner. Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation. Especially when children do not know what else to do, they learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others.[25]

A series of studies by Bandura (et als. 1963) looked at the impact of television, particularly commercials, on the behavior of children. Are children more likely to act out aggressively when they see this behavior modeled? What if they see it being reinforced? Bandura began by conducting an experiment in which he showed children a film of a woman hitting an inflatable clown or “bobo” doll. Then the children were allowed in the room where they found the doll and immediately began to hit it. This was without any reinforcement whatsoever. Not only that, but they found new ways to behave aggressively. It’s as if they learned an aggressive role. [26]

If children learn behavior by observation, what does the research say about witnessing media violence? Some studies suggest that violent television shows, movies, and video games may also have antisocial effects although further research needs to be done to understand the correlational and causational aspects of media violence and behavior. Some studies have found a link between viewing violence and aggression seen in children (Anderson & Gentile, 2008; Kirsch, 2010; Miller, Grabell, Thomas, Bermann, & Graham-Bermann, 2012). These findings may not be surprising, given that a child graduating from high school has been exposed to around 200,000 violent acts including murder, robbery, torture, bombings, beatings, and rape through various forms of media (Huston et al., 1992). Not only might viewing media violence affect aggressive behavior by teaching people to act that way in real-life situations but it has also been suggested that repeated exposure to violent acts also desensitizes people to it. Psychologists are working to understand this dynamic.[27]

However, many children watch violent media and do not become violent. Research has found that, just as children learn to be aggressive through observational learning, they can also learn prosocial behaviors in the same way (Seymour, Yoshida, & Dolan, 2009). Simple exposure to a model is not enough to explain observational learning. A variety of factors have been shown to explain the likelihood that exposure will lead to learning and modeling. Similarity, proximity, frequency of exposure, reinforcement, and likeability of the model are all related to learning. In addition, people can choose what to watch and whom to imitate. Observational learning is dependent on many factors, so people are well advised to select models carefully, both for themselves and their children.[28]

Media and Self-Understanding

Young children begin developing social understanding very early in life. While children of early, middle, and late development include other peoples’ appraisals of them in their self-concept, they also receive messages from the media about how they should look and act. Movies, music videos, the internet, and advertisers can all create cultural images of what is desirable or undesirable and this too can influence a child’s self-concept. [29]

When children internalize and compare themselves to these cultural images, it can affect their self-esteem, which is defined as an evaluation of one’s identity. If there is a discrepancy between how children view themselves and what they consider to be their ideal selves, their self-esteem can be negatively affected.[30]

For example, social media can have diverse effects on self-esteem. Think about Facebook or Twitter. Perhaps you know somebody who constantly posts about themselves in order for others to press like, which makes them feel validated and appreciated. However, if somebody doesn’t respond in the way that they hope for, they might start to feel anxious and even a bit paranoid.[31]

When children internalize and compare themselves to cultural images, it can affect their self-esteem. [32]

Recess and Physical Education

Recess

Recess is a time for free play and Physical Education (PE) is a structured program that teaches skills, rules, and games. They’re a big part of physical fitness for school-age children. For many children, PE and recess are the key components in introducing children to sports. After years of schools cutting back on recess and PE programs, there has been a turnaround, prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and related health issues. Despite these changes, currently, only the state of Oregon and the District of Columbia meet PE guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity in elementary school and 225 minutes in middle school (SPARC, 2016).

Organized Sports: Pros and Cons

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. Nearly 3 million children play soccer in the United States (United States Youth Soccer, 2012). This activity promises to help children build social skills, improve athletically and learn a sense of competition. However, the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children's activities are no longer children's activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U. S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling engaged in during practice and to allow children to play more freely and choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. Children’s participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development

- Better academic performance

Yet, a study on children’s sports in the United States (Sabo & Veliz, 2008) has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports. Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport.

This study also found that fathers may not be providing their daughters as much support as they do their sons. While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentors who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Sabo and Veliz also found that children in suburban neighborhoods had much higher participation in sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. In addition, Caucasian girls and boys participated in organized sports at higher rates than minority children. With a renewed focus, males and females can benefit from all sports and physical activity.

The recent Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (2016) report on the “State of Play” in the United States highOrganizelights a disturbing trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise. In addition, e-sports, which as SPARC writes is about as much a sport as poker, involves children watching other children play video games. Over half of males, and about 20% of females, aged 12-19, say they are fans of e-sports. Play is an important part of childhood and physical activity has been proven to help children develop and grow. Adults and caregivers should look at what children are doing within their day to prioritize the activities that should be focused on.[33]

Participation in organized sports has many advantages. [latex]Image by Pixabay is licensed by CC0.[/latex]

Participation in organized sports has many advantages. [latex]Image by Pixabay is licensed by CC0.[/latex]

Stress and Coping

The term stress as it relates to the human condition first emerged in the scientific literature in the 1930s, but it did not enter the popular vernacular until the 1970s (Lyon, 2012). Today, we often use the term loosely in describing a variety of unpleasant feeling states; for example, we often say we are stressed out when we feel frustrated, angry, conflicted, overwhelmed, or fatigued. Despite the widespread use of the term, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision.

Researchers have had a difficult time agreeing on an acceptable definition of stress. Some have conceptualized stress as a demanding or threatening event or situation (e.g., a high-stress job, overcrowding, and long commutes to work). Such conceptualizations are known as stimulus-based definitions because they characterize stress as a stimulus that causes certain reactions. Stimulus-based definitions of stress are problematic, however, because they fail to recognize that people differ in how they view and react to challenging life events and situations. For example, a conscientious student who has studied diligently all semester would likely experience less stress during final exam week than would a less responsible, unprepared student.

Others have conceptualized stress in ways that emphasize the physiological responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations (e.g., increased arousal). These conceptualizations are referred to as response-based definitions because they describe stress as a response to environmental conditions. For example, the endocrinologist Hans Selye, a famous stress researcher, once defined stress as the “response of the body to any demand, whether it is caused by, or results in, pleasant or unpleasant conditions” (Selye, 1976, p. 74). Selye’s definition of stress is response-based in that it conceptualizes stress chiefly in terms of the body’s physiological reaction to any demand that is placed on it. Neither stimulus-based nor response-based definitions provide a complete definition of stress. Many of the physiological reactions that occur when faced with demanding situations (e.g., accelerated heart rate) can also occur in response to things that most people would not consider to be genuinely stressful, such as receiving unanticipated good news: an unexpected promotion or raise.

The stress response, as noted earlier, consists of a coordinated but complex system of physiological reactions that are called upon as needed. These reactions are beneficial at times because they prepare us to deal with potentially dangerous or threatening situations (for example, recall our old friend, the fearsome bear on the trail). However, health is affected when physiological reactions are sustained, as can happen in response to ongoing stress.

If the reactions that compose the stress response are chronic or if they frequently exceed normal ranges, they can lead to cumulative wear and tear on the body, in much the same way that running your air conditioner on full blast all summer will eventually cause wear and tear on it. For example, the high blood pressure that a person under considerable job strain experiences might eventually take a toll on his heart and set the stage for a heart attack or heart failure. Also, someone exposed to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol might become vulnerable to infection or disease because of weakened immune system functioning (McEwen, 1998).[34]

Stress on Young Children

Children experience different types of stressors. Normal, everyday stress can provide an opportunity for young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Even more, long-lasting stressful events, such as changing schools or losing a loved one, can be managed fairly well. Children who experience toxic stress or who live in extremely stressful situations of abuse over long periods of time can suffer long-lasting effects. The structures in the midbrain or limbic systems, such as the hippocampus and amygdala, can be vulnerable to prolonged stress during early childhood (Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008). High levels of the stress hormone cortisol can reduce the size of the hippocampus and affect the child's memory abilities. Stress hormones can also reduce immunity to disease. The brain exposed to long periods of severe stress can develop a low threshold making the child hypersensitive to stress in the future.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

The toxic stress that young children endure can have a significant impact on their later lives. According to Merrick, Ford, Ports, and Guinn (2018), the foundation for lifelong health and well-being is created in childhood, as positive experiences strengthen biological systems while adverse experiences can increase mortality and morbidity. All types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur before the age of 18 are referred to as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (CDC, 2019). ACEs have been linked to risky behaviors, chronic health conditions, low life potential, and early death, and as the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk for these results.[35]

When a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity without adequate adult support, the child’s stress response systems can be activated and disrupt the development of the brain and other organ systems (Harvard University, 2019). Further, ACEs can increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment, well into the adult years. Felitti et al. (1998) found that those who had experienced four or more ACEs compared to those who had experienced none, had increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, suicide attempt, increase in smoking, poor self-rated health, more sexually transmitted diseases, an increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity. More ACEs showed an increased relationship to the presence of adult diseases including heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. Overall, those with multiple ACEs were likely to have multiple health risk factors later in life.[36]

The ACE Pyramid represents the conceptual framework for the ACE Study, which has uncovered how adverse childhood experiences are strongly related to various risk factors for disease throughout the lifespan. Graph showing how adverse childhood experiences are related to risk factors for disease, health, and social well-being. The lifespan is represented as an arrow ascending past the layers of a pyramid, beginning with Adverse Childhood Experiences and moving through Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Impairment; Adoption of Health-risk Behaviors; Disease, Disability, and Social Problems; and finally Early Death. Smaller arrows depict gaps in scientific knowledge about the links between Adverse Childhood Experiences and later risk factors. [37]

The ACE Pyramid represents the conceptual framework for the ACE Study, which has uncovered how adverse childhood experiences are strongly related to various risk factors for disease throughout the lifespan. Graph showing how adverse childhood experiences are related to risk factors for disease, health, and social well-being. The lifespan is represented as an arrow ascending past the layers of a pyramid, beginning with Adverse Childhood Experiences and moving through Social, Emotional, and Cognitive Impairment; Adoption of Health-risk Behaviors; Disease, Disability, and Social Problems; and finally Early Death. Smaller arrows depict gaps in scientific knowledge about the links between Adverse Childhood Experiences and later risk factors. [37]

Some groups have been found to be at a greater risk for experiencing ACEs. Merrick et al. (2018) reviewed the results from the 2011-2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which included an ACE module consisting of questions adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Each question was collapsed into one of the eight ACE categories: physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, household mental illness, household substance use, household domestic violence, incarcerated household member, and parental separation or divorce. The results indicated that 25% of the sample had been exposed to three or more ACEs, and although ACEs were found across all demographic groups, those who identified as Black, multiracial, lesbian/gay/bisexual, having less than high school education, being low income, and unemployed experienced significantly higher ACE exposure. Assisting families and providing children with supportive and responsive adults can help prevent the negative effects of ACEs.

Resiliency

Being able to overcome challenges and successfully adapt is resiliency. Even young children can exhibit strong resilience to harsh circumstances. [38] However, we can’t “make” children resilient, but we can explore those qualities and skills that help them develop key elements of resiliency. Ann Masten, one of the foremost researchers of resilience in children, writes, “Resilience does not come from rare and special qualities, but from the everyday magic of ordinary, normative human resources in the minds, brains, and bodies of children, in their families and relationships, and in their communities.” This “ordinary magic” means that children will be more able to adapt to adversity and threats when their basic human systems are nurtured and supported.

Factors that Contribute to Childhood Resilience

While many factors contribute to resilience, three stand out: cognitive development, self-regulation, and relationships with caring adults.

Cognitive Development/Problem-solving Skills

As a species, we have been solving problems since the beginning of time. Watch a child play and you will see that his/her problem-solving skills are nearly always at work. Infants attempt to soothe themselves by figuring out how to put their thumbs in their mouths or crying for a caregiver. Toddlers try to fit shapes into shape sorters. As children mature, the problems they solve get more complex. Solving problems engages our prefrontal cortex, sometimes called the “thinking brain,” which is the seat of our executive function. During times of stress and trauma, this part of our brain is typically shut down so that our body can respond to the threats it is facing. By helping children engage in problem-solving activities, they not only gain a sense of self-efficacy and mastery, they also re-engage the parts of their brain that may have been offline. Because the neural pathways of young brains are still being wired, the more we can engage and reinforce healthy pathways, the better. Developing problem-solving skills also helps children with self-regulation skills, another key quality that fosters resilience.

Self-regulation

Self-regulation is the ability to control oneself in a variety of ways. Infants develop regular sleep-wake patterns. Schoolchildren learn to raise their hands and wait patiently to be called on rather than shouting out an answer. College students concentrate for hours on a research paper, delaying the gratification that might come with being outdoors on a sunny day. Self-regulation has been identified as “the cornerstone” of child development. In the seminal publication From Neurons to Neighborhoods (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2000), experts conclude, “Development may be viewed as an increased capacity for self-regulation, seen particularly in the child’s ability to function more independently in a personal and social context.” It involves working memory, the ability to focus on a goal, tolerance for frustration, and controlling and expressing one’s emotions appropriately and in context. Self-regulation is key for academic and social success and plays a significant role in mental health outcomes—all things that can be a challenge for children experiencing homelessness and other stressors.

Relationships with Caring Adults

Ideally, we form close attachment relationships with our primary caregiver(s) beginning at birth. As we get older, those relationships extend to teachers, neighbors, family, friends, coaches, and others. Disrupted attachment relationships can be devastating for young children because they are still developing an internal working model of what relationships look like and because they rely so intensively on their caregivers to get their basic needs met. By developing relationships with caring adults, whether they be parents, family members, coaches, teachers, or neighbors, children learn about healthy relationships—ones that are consistent, predictable, and safe. They receive guidance, comfort, and mentoring.[39]

Chronic Health Conditions

Chronic Health Conditions in Childhood

About 25% of children in the United States aged 2 to 8 years have a chronic health condition such as asthma, obesity, other physical conditions, and behavior/learning problems. The healthcare needs of children with chronic illness can be complex and continuous and include both daily management and addressing potential emergencies. Asthma and Diabetes are examples of two health conditions in childhood that require careful management both inside and outside of the home.

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic disease that affects your airways. Your airways are tubes that carry air in and out of your lungs. If you have asthma, the inside walls of your airways become sore and swollen.

In the United States, about 20 million people have asthma. Nearly 9 million of them are children. Children have smaller airways than adults, which makes asthma especially serious for them. Children with asthma may experience wheezing, coughing, chest tightness, and trouble breathing, especially early in the morning or at night.

Many things can cause asthma including allergens, irritants, weather, exercise, and infections. When asthma symptoms become worse than usual, it is called an asthma attack. Asthma is treated with two kinds of medicines: quick-relief medicines to stop asthma symptoms and long-term control medicines to prevent symptoms.

Some common triggers [40]

Diabetes

Until recently, the common type of diabetes in children and teens was type 1. It was called juvenile diabetes. With Type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not make insulin. Insulin is a hormone that helps glucose, or sugar, get into your cells to give them energy. Without insulin, too much sugar stays in the blood.

Now younger people are also getting type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes used to be called adult-onset diabetes. But now it is becoming more common in children and teens, due to more obesity. With Type 2 diabetes, the body does not make or use insulin well.

Children have a higher risk of type 2 diabetes if they are overweight or have obesity, have a family history of diabetes, or are not active. Children who are African American, Hispanic, Native American/Alaska Native, Asian American, or Pacific Islander also have a higher risk. To lower the risk of type 2 diabetes in children:

- Have them maintain a healthy weight

- Be sure they are physically active

- Have them eat smaller portions of healthy foods

- Limit time with the TV, computer, and video

Children and teens with type 1 diabetes may need to take insulin. Type 2 diabetes may be controlled with diet and exercise. If not, patients will need to take oral diabetes medicines or insulin. A blood test called the A1C can check on how you are managing your diabetes.[41]

- "Child, Family, and Community" by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work ↵

- Images retrieved from pixabay.com are licensed under CC0 ↵

- Images retrieved from pixabay.com are licensed under CC0[ ↵

- Images retrieved from pixabay.com are licensed under CC0 ↵

- Images retrieved from pixabay.com are licensed under CC0 ↵

- Image retrieved from pixabay.com are licensed under CC0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- from "Child, Family, and Community" by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image retrieved from "Child, Family, and Community" by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work[4] "Child, Family, and Community" by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work ↵

- "Child, Family, and Community" by Rebecca Laff and Wendy Ruiz, College of the Canyons is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Introduction to Psychology by the University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, ↵

- Psychology2e from Openstax licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Screen Time vs Lean Time was retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Television and Video Viewing Time Among Children Aged 2 Years --- Oregon, 2006--2007 retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Hanson, Katherine, "THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1011. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1011. Part of the Developmental Psychology Commons[14] Effect of Media Use on Adolescent Body Weight.by Eun Me Cha, MPH, PhD; Deanna M. Hoelscher, PhD Nalini Ranjit, PhD, Baojiang Chen, PhD; Kelley Pettee Gabriel, MS, PhD, Steven Kelder, MPH, PhD, ; Debra L. Saxton, MS was retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Effect of Media Use on Adolescent Body Weight.by Eun Me Cha, MPH, PhD; Deanna M. Hoelscher, PhD Nalini Ranjit, PhD, Baojiang Chen, PhD; Kelley Pettee Gabriel, MS, PhD, Steven Kelder, MPH, PhD, ; Debra L. Saxton, MS was retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Screen Time and Children from retrieved from MedlinePlus U.S. National Library of Medicine – Public domain ↵

- Effect of Media Use on Adolescent Body Weight.by Eun Me Cha, MPH, PhD; Deanna M. Hoelscher, PhD Nalini Ranjit, PhD, Baojiang Chen, PhD; Kelley Pettee Gabriel, MS, PhD, Steven Kelder, MPH, PhD, ; Debra L. Saxton, MS was retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Television and Video Viewing Time Among Children Aged 2 Years --- Oregon, 2006--2007 retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Screen Time vs Lean Time was retrieved from the CDC – public domain ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Psychology - Learning by Openstax is licensed under CC-BY-4. 0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Introduction to Psychology Adapted by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- The Media And Self-Esteem. by Kim Lyon was retrieved from Explorable.com and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image from Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0. ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Psychology - What is Stress? by Openstax is licensed under CC-BY-4. 0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160116162134/http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/pyramid.html . Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC SA-3. ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Childhood Resilience retrieved from SAMSA HHS.gov – public domain ↵

- Asthma Triggers by 7Mike5000 retrieved from Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC SA-3. ↵

- Diabetes in Children and Teens retrieved from MedlinePlus U.S. National Library of Medicine – Public domain ↵

two or more people who are related by blood, marriage, or adoption

an extended family, typically consisting of three or more generations and their spouses, living together as a single household.

vary from the traditional definition of family to include single parent families, foster families, same-sex couples, child-free families as well as other forms.

a broad conceptual model that focuses on the relationships between and among interacting individuals in a family and combines core concepts from general systems theory, cybernetics, family development theory, object relations theory, and social learning theory. Underlying various family therapies, the theory stresses that therapists must see the whole family, rather than work only with individual members, to create constructive, systemic, and lasting changes in the family

The family stress model (FSM) suggests that stress, particularly economic stress, hinders effective parenting

Singlehood families consist of a person who lives with a child or children and who does not have a spouse or live-in partner to assist in the upbringing or support of the child.

A family unit consisting of two parents and their dependent children (whether biological or adopted). With various modifications, the nuclear family has been and remains the norm in developed Western societies.

The state of living together as sexual and domestic partners without being married.

a homosexual couple living together with children.

a family unit formed by the union of parents wherein one or both bring a child or children from a previous union (or unions) into the new household. Also called step family

includes any family members beyond the nuclear family such as grandparents, cousins, aunts, uncles. It is also called a consanguineous family.

is a term that refers to a non biologically related group of people established to provide ongoing social support

marriage to only one spouse at a time

marriage to more than one spouse at the same time.

Kinship care is defined as the full-time care, nurturing, and protection of a child by relatives, members of their Tribe or clan, godparents, stepparents, or other adults who have a family relationship to a child.

the legal process by which an infant or child is permanently placed with a family other than his or her birth family.

the legal dissolution of marriage, leaving the partners free to remarry.

ways in which parents interact with their children—with most classifications varying on the dimensions of emotional warmth (warm vs. cold) and control (high in control vs. low in control).

refers to the extent to which parents intentionally foster individuality, self-regulation, and self-assertion by being attuned, supportive, and acquiescent to children’s special needs and demands.

refers to the claims parents make on children to become integrated into the family whole, by their maturity demands, supervision, disciplinary efforts and willingness to confront the child who disobeys. Also referred to as parental control.

attempts to behave in a nonpunitive, acceptant and affirmative manner towards the child's impulses, desires, and actions.

attempts to shape, control, and evaluate the behavior and attitudes of the child

attempts to direct the child's activities but in a rational, issue-oriented manner

do not set firm boundaries or high standards and are indifferent to their children’s needs and uninvolved in their lives.

control attempts that include parenting practices such as intrusiveness, guilt induction, and love withdrawal

The introduction of a stimulus that will likely increase the probability of behavior.

any change in behavior that occurs after that behavior reduces the likelihood of repeating that behavior.

the production of a new behavior through the reinforcement of successive approximations to that behavior.

the general view that learning is largely or wholly due to modeling, imitation, and other social interactions

the degree to which the qualities and characteristics contained in one’s self-concept are perceived to be positive. It reflects a person’s physical self-image, view of his or her accomplishments and capabilities, and values and perceived success in living up to them, as well as the ways in which others view and respond to that person.

esports are video games that are played in a highly organized competitive environment. These games can range from popular, team-oriented multiplayer online battle arenas (MOBAs), to single player first person shooters, to survival battle royales, to virtual reconstructions of physical sports.

the physiological or psychological response to internal or external stressors. Stress involves changes affecting nearly every system of the body, influencing how people feel and behave

traumatic events that occur before a child reaches the age of 18. ACEs include all types of abuse and neglect, such as parental substance use, incarceration, and domestic violence. ACEs can also include situations that may cause trauma for a child, such as having a parent with a mental illness or being part of a family going through a divorce.

Behavior risk factor surveillance system is a United States national self-report telephone survey that provides prevalence data concerning behavioral risk factors associated with the nation's most common health conditions.

the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and behavioral flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands.