13 Social Cognition and Peer Relationships

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 13, you should be equipped to:

- Describe Theory of Mind

- Describe play and the importance of play

- Discuss the impact of peer relationships and identify the different Sociometric Status categories.

- Identify and describe the different types of bullying and their outcomes, and compare ways to effectively prevent bullying.

Theory of Mind

What is Theory of Mind?

Theory of mind refers to one’s ability to think about other people’s thoughts and to perceive and interpret other people’s behavior in terms of their mental states. This mental “mind reading” helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development.[1] Infants and toddlers have a relatively simple theory of mind. They are aware of some basic characteristics: what people are looking at is a sign of what they are paying attention to; people act intentionally and are goal directed; people have positive and negative feelings in response to things around them; and people have different perceptions, goals, and feelings. Children add to this mental map as their awareness grows. From infancy on, developing theory of mind permeates everyday social interactions—affecting what and how children learn, how they react to and interact with other people, how they assess the fairness of an action, and how they evaluate themselves.

One-year-olds, for example, will look in their mother’s direction when faced with someone or something unfamiliar to “read” mother’s expression and determine whether this is a dangerous or benign unfamiliarity. Infants also detect when an adult makes eye contact, speaks in an infant-directed manner (such as using higher pitch and melodic intonations), and responds contingently to the infant’s behavior. Under these circumstances, infants are especially attentive to what the adult says and does, thus devoting special attention to social situations in which the adult’s intentions are likely to represent learning opportunities.

Other examples also illustrate how a developing theory of mind underlies children’s emerging understanding of the intentions of others. Take imitation, for example. It is well established that babies and young children imitate the actions of others. Children as young as 14 to 18 months are often imitating not the literal observed action but the action they thought the actor intended—the goal or the rationale behind the action (Gergely et al., 2002; Meltzoff, 1995). Word learning is another example in which babies’ reasoning based on theory of mind plays a crucial role. By at least 15 months old, when babies hear an adult label an object, they take the speaker’s intent into account by checking the speaker’s focus of attention and deciding whether they think the adult indicated the object intentionally. Only when babies have evidence that the speaker intended to refer to a particular object with a label will they learn that word (Baldwin, 1991; Baldwin and Moses, 2001; Baldwin and Tomasello, 1998).

Babies can also perceive the unfulfilled goals of others and intervene to help them; this is called “shared intentionality.” Babies as young as 14 months old who witness an adult struggling to reach for an object will interrupt their play to crawl over and hand the object to the adult (Warneken and Tomasello, 2007). By the time they are 18 months old, shared intentionality enables toddlers to act helpfully in a variety of situations; for example, they pick up dropped objects for adults who indicate that they need assistance (but not for adults who dropped the object intentionally) (Warneken and Tomasello, 2006). Developing an understanding of others’ goals and preferences and how to facilitate them affects how young children interpret the behavior of people they observe and provides a basis for developing a sense of helpful versus undesirable human activity that is a foundation for later development of moral understanding (cf. Bloom, 2013; Hamlin et al., 2007; Thompson, 2012, 2015).[2]

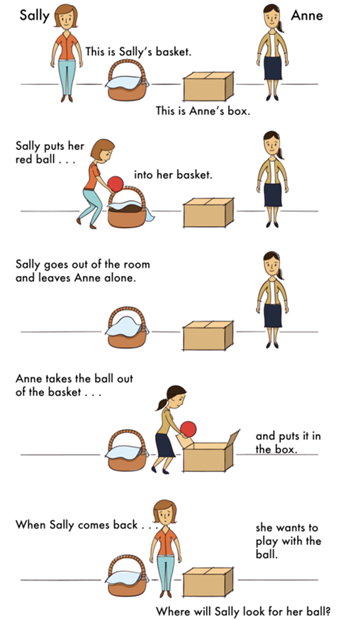

One common method for determining if an older child has reached this mental milestone is the false-belief task. The research in the area of false beliefs began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who noted the response of young children to what they called the “Sally-Anne Test.” During this test, the child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket because that is where she put it and thinks it is, but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three-year-old’s have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). Even adults need to think through this task (Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they believe rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001).[3]

The Sally-Anne task [4]

The Role of Theory of Mind in Social Life

Children form an alliance to complete the puzzle. [5]

Put yourself in this scene: You observe two people’s movements, one behind a large wooden object, the other reaching behind him and then holding a thin object in front of the other. Without a theory of mind, you would neither understand what this movement stream meant nor be able to predict either person’s likely responses. With the capacity to interpret certain physical movements in terms of mental states, perceivers can parse this complex scene into intentional actions of reaching and giving (Baird & Baldwin, 2001); they can interpret the actions as instances of offering and trading; and with an appropriate cultural script, they know that all that was going on was a customer pulling out her credit card with the intention to pay the cashier behind the register. People’s theory of mind thus frames and interprets perceptions of human behavior in a particular way—as perceptions of agents who can act intentionally and who have desires, beliefs, and other mental states that guide their actions (Perner, 1991; Wellman, 1990).

Not only would social perceivers without a theory of mind be utterly lost in a simple payment interaction; without a theory of mind, there would probably be no such things as cashiers, credit cards, and payment (Tomasello, 2003). Plain and simple, humans need to understand minds in order to engage in the kinds of complex interactions that social communities (small and large) require. And it is these complex social interactions that have given rise, in human cultural evolution, to houses, cities, and nations; to books, money, and computers; to education, law, and science. The list of social interactions that rely deeply on theory of mind is long; here are a few highlights.

- Teaching another person new actions or rules by considering what the learner knows or doesn’t know and how one might best make him understand.

- Learning the words of a language by monitoring what other people attend to and are trying to do when they use certain words.

- Figuring out our social standing by trying to guess what others think and feel about us.

- Sharing experiences by telling a friend how much we liked a movie or by showing her something beautiful.

- Collaborating on a task by signaling to one another that we share a goal and understand and trust the other’s intention to pursue this joint goal.[6]

The Mental Processes Underlying Theory of Mind

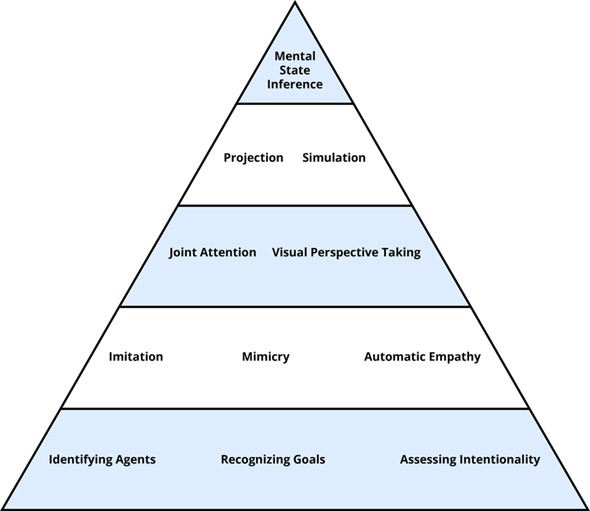

The first thing to note is that “theory of mind” is not a single thing. What underlies people’s capacity to recognize and understand mental states is a whole host of components—a toolbox, as it were, for many different but related tasks in the social world (Malle, 2008). The figure below shows some of the most important tools, organized in a way that reflects the complexity of involved processes: from simple and automatic on the bottom to complex and deliberate on the top. This organization also reflects development—from tools that infants master within the first 6–12 months to tools they need to acquire over the next 3–5 years. Strikingly, the organization also reflects evolution: monkeys have available the tools on the bottom; chimpanzees have available the tools at the second level, but only humans master the remaining tools above. Let’s look at a few of them in more detail.

Some of the major tools of the theory of mind.

Agents, Goals, and Intentionality

The agent category allows humans to identify those moving objects in the world that can act on their own. Features that even very young children take to be indicators of being an agent include being self-propelled, having eyes, and reacting systematically to the interaction partner’s behavior, such as following gaze or imitating (Johnson, 2000; Premack, 1990).

The process of recognizing goals builds on this agent category because agents are characteristically directed toward goal objects, which means they seek out, track, and often physically contact said objects. Even before the end of their first year, infants recognize that humans reach toward an object they strive for even if that object changes location or if the path to the object contains obstacles (Gergely, Nádasdy, Csibra, & Bíró, 1995; Woodward, 1998). What it means to recognize goals, therefore, is to see the systematic and predictable relationship between a particular agent pursuing a particular object across various circumstances.

Through learning to recognize the many ways by which agents pursue goals, humans learn to pick out behaviors that are intentional. The concept of intentionality is more sophisticated than the goal concept. For one thing, human perceivers recognize that some behaviors can be unintentional even if they were goal-directed—such as when you unintentionally make a fool of yourself even though you had the earnest goal of impressing your date. To act intentionally you need, aside from a goal, the right kinds of beliefs about how to achieve the goal. Moreover, the adult concept of intentionality requires that an agent have the skill to perform the intentional action in question: If I am flipping a coin, trying to make it land on heads, and if I get it to land on heads on my first try, you would not judge my action of making it land on heads as intentional—you would say it was luck (Malle & Knobe, 1997).

Imitation, Synchrony, and Empathy

Imitation and empathy are two other basic capacities that aid the understanding of mind from childhood on (Meltzoff & Decety, 2003). Imitation is the human tendency to carefully observe others’ behaviors and do as they do—even if it is the first time the perceiver has seen this behavior. A subtle, automatic form of imitation is called mimicry, and when people mutually mimic one another they can reach a state of synchrony. Have you ever noticed when two people in conversation take on similar gestures, body positions, and even tone of voice? They “synchronize” their behaviors by way of (largely) unconscious imitation. Such synchrony can happen even at very low levels, such as negative physiological arousal (Levenson & Ruef, 1992), though the famous claim of synchrony in women’s menstrual cycles is a myth (Yang & Schank, 2006). Interestingly, people who enjoy an interaction synchronize their behaviors more, and increased synchrony (even manipulated in an experiment) makes people enjoy their interaction more (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). Some research findings suggest that synchronizing is made possible by brain mechanisms that tightly link perceptual information with motor information (when I see you move your arm, my arm-moving program is activated). In monkeys, highly specialized so-called mirror neurons fire both when the monkey sees a certain action and when it performs that same action (Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001). In humans, however, things are a bit more complex. In many everyday settings, people perceive uncountable behaviors and fortunately don’t copy all of them (just consider walking in a crowd—hundreds of your mirror neurons would fire in a blaze of confusion). Human imitation and mirroring are selective, triggering primarily actions that are relevant to the perceiver’s current state or aim.

Automatic empathy builds on imitation and synchrony in a clever way. If Bill is sad and expresses this emotion in his face and body, and if Elena watches or interacts with Bill, then she will subtly imitate his dejected behavior and, through well-practiced associations of certain behaviors and emotions, she will feel a little sad as well (Sonnby-Borgström, Jönsson, & Svensson, 2003). Thus, she empathizes with him—whether she wants to or not. Try it yourself. Type “sad human faces” into your Internet search engine and select images from your results. Look at 20 photos and pay careful attention to what happens to your face and to your mood. Do you feel almost a “pull” of some of your facial muscles? Do you feel a tinge of melancholy?

Joint Attention, Visual Perspective Taking

Going beyond the automatic, humans are capable of actively engaging with other people’s mental states, such as when they enter into situations of joint attention—like Marissa and Noah, who are each looking at an object and are both aware that each of them is looking at the object. This sounds more complicated than it really is. Just point to an object when a 3-year-old is around and notice how both the child and you check in with each other, ensuring that you are really jointly engaging with the object. Such shared engagement is critical for children to learn the meaning of objects—both their value (is it safe and rewarding to approach?) and the words that refer to them (what do you call this?). When I hold up my keyboard and show it to you, we are jointly attending to it, and if I then say it’s called “Tastatur” in German, you know that I am referring to the keyboard and not to the table on which it had been resting.

Another important capacity of engagement is visual perspective taking: You are sitting at a dinner table and advise another person on where the salt is—do you consider that it is to her left even though it is to your right? When we overcome our egocentric perspective this way, we imaginatively adopt the other person’s spatial viewpoint and determine how the world looks from their perspective. In fact, there is evidence that we mentally “rotate” toward the other’s spatial location, because the farther away the person sits (e.g., 60, 90, or 120 degrees away from you) the longer it takes to adopt the person’s perspective (Michelon & Zacks, 2006).

Projection, Simulation (and the Specter of Egocentrism)

When imagining what it might be like to be in another person’s psychological position, humans have to go beyond mental rotation. One tool to understand the other’s thoughts or feelings is a simulation—using one’s own mental states as a model for others’ mental states: “What would it feel like sitting across from the stern interrogator? I would feel scared . . .” An even simpler form of such modeling is the assumption that the other thinks, feels, and wants what we do—which has been called the “like-me” assumption (Meltzoff, 2007) or the inclination toward social projection (Krueger, 2007). In a sense, this is an absence of perspective-taking, because we assume that the other’s perspective equals our own. This can be an effective strategy if we share with the other person the same environment, background, knowledge, and goals, but it gets us into trouble when this presumed common ground is in reality lacking. Let’s say you know that Brianna doesn’t like Fred’s new curtains, but you hear her exclaim to Fred, “These are beautiful!” Now you have to predict whether Fred can figure out that Brianna was being sarcastic. It turns out that you will have a hard time suppressing your own knowledge in this case and you may overestimate how easy it is for Fred to spot the sarcasm (Keysar, 1994). Similarly, you will overestimate how visible that pimple is on your chin—even though it feels big and ugly to you, in reality very few people will ever notice it (Gilovich & Savitsky, 1999). So the next time when you spot a magnificent bird high up in the tree and you get impatient with your friend who just can’t see what is clearly obvious, remember: it’s obvious to you.

What all these examples show is that people use their own current state—of knowledge, concern, or perception—to grasp other people’s mental states. And though they often do so correctly, they also get things wrong at times. This is why couples counselors, political advisors, and Buddhists agree on at least one thing: we all need to try harder to recognize our egocentrism and actively take other people’s perspectives—that is, grasp their actual mental states, even if (or especially when) they are different from our own.[7]

Explicit Mental State Inference

The ability to truly take another person’s perspective requires that we separate what we want, feel, and know from what the other person is likely to want, feel, and know. To do so humans make use of a variety of information. For one thing, they rely on stored knowledge—both general knowledge (“Everybody would be nervous when threatened by a man with a gun”) and agent-specific knowledge (“Joe was fearless because he was trained in martial arts”). For another, they critically rely on perceived facts of the concrete situation—such as what is happening to the agent, the agent’s facial expressions and behaviors, and what the person saw or didn’t see.

This capacity of integrating multiple lines of information into a mental-state inference develops steadily within the first few years of life, and this process has led to a substantial body of research that began with the Sally-Anne, False Belief Task previously discussed.[8]

Autism and Theory of Mind

Another way of appreciating the enormous impact that theory of mind has on social interactions is to study what happens when the capacity is severely limited, as in the case of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In a landmark study, Baron-Cohen, Leslie and Frith (1985) reported that children with autism, who suffer from severe impairment in social interaction and communication, do not pass the false belief test. This seminal study inspired many follow-up studies, both in typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The accumulation of the studies supports the proposal that children with ASD show atypical development of the capacity for theory of mind. The most consistent finding is that before the verbal mental age of 11 years, children with ASD do not pass various versions of the false belief test. Whereas typical 4-year-olds correctly anticipate others’ behavior based on the attribution of false belief, children with ASD, at the same mental age or even higher, incorrectly predict behavior based on reality without taking the other person’s epistemic states (e.g. knowledge and belief) into account (Happé, 1995,). This result has been interpreted as evidence that children with ASD (with verbal skills equivalent to typically developing children of under 11 years) fail to represent others’ epistemic mental states, or at least fail to do so when others’ mental states are different from the child’s own. Based on these findings, some scientists suggested that the difficulty in social interaction and communication in ASD derives from impairment in theory of mind (Mindblindness theory, Baron-Cohen, 1995).

However, there are two major problems in the standard false belief test. Firstly, it is a cognitively demanding test. To pass the test, a child has to remember the sequence of the presented event, correctly understand the experimenter’s question, and inhibit their initial response to answer the actual location of object (Birch and Bloom, 2003). Thus, it is possible that despite having the capacity to represent another person’s mental state, children fail the standard false belief test because of a weaker cognitive control or difficulty in pragmatic understanding. Secondly, individuals with ASD with higher verbal skills do pass the standard false belief test.

However, the qualitative difficulties in social interaction and communication persist even in these “high-functioning” individuals with ASD. For example, in an experimental setting, they still show subtle difficulties in understanding non-literal utterance (Happé, 1994) and faux-pas (Baron-Cohen, O’Riordan, Stone, Jones, and Plaisted, 1999), and fail to correctly infer complex mental states from photographs of eyes (Baron-Cohen, Jolliffe, Mortimore, and Robertson, 1997) and from cartoon animations (Castelli, Frith, Happé, and Frith, 2002).[9]

Although to-date questions have arisen regarding the universality and uniqueness of theory-of-mind deficits in autism, and about how this hypothesis could explain early symptoms including restricted interests, or repetitive behaviors, studies repeatedly show reduced performance on tasks that assess theory of mind in ASD. Thus, theory of mind is still considered crucial for understanding social performance in ASD.[10]

Play

What is Play?

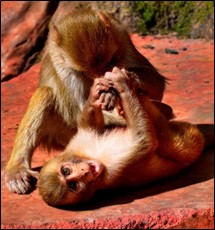

“Play is behavior that looks as if it has no purpose,” says NIH psychologist Dr. Stephen Suomi. “It looks like fun, but it actually prepares for a complex social world.” Evidence suggests that play can help boost brain function, increase fitness, improve coordination and teach cooperation. Suomi notes that all mammals—from mice to humans—engage in some sort of play. His research focuses on rhesus monkeys. While he’s cautious about drawing parallels between monkeys and people, his studies offer some general insights into the benefits of play.

All mammals engage in some sort of play. [11]

Active, vigorous social play during development helps to sculpt the monkey brain. The brain grows larger. Connections between brain areas may strengthen. Play also helps monkey youngsters learn how to fit into their social group, which may range from 30 to 200 monkeys in 3 or 4 extended families. Both monkeys and humans live in highly complex social structures, says Suomi. “Through play, rhesus monkeys learn to negotiate, to deal with strangers, to lose gracefully, to stop before things get out of hand, and to follow rules,” he says. These lessons prepare monkey youngsters for life after they leave their mothers.

Play may have similar effects in the human brain. Play can help lay a foundation for learning the skills we need for social interactions. If human youngsters lack playtime, says Dr. Roberta Golinkoff, an infant language expert at the University of Delaware, “social skills will likely suffer. You will lack the ability to inhibit impulses, to switch tasks easily and to play on your own.” Play helps young children master their emotions and make their own decisions. It also teaches flexibility, motivation, and confidence.

Kids don’t need expensive toys to get a lot out of playtime. “Parents are children’s most enriching plaything,” says Golinkoff. Playing and talking to babies and children are vital for their language development. Golinkoff says that kids who talk with their parents tend to acquire a vocabulary that will later help them in school. “In those with parents who make a lot of demands, language is less well developed,” she says. The key is not to take over the conversation, or you’ll shut it down.[12]

Types of Play

Play can be viewed as a spontaneous, voluntary, pleasurable, and flexible activity involving a combination of body, object, symbol use, and relationships. In contrast to games, play behavior is more disorganized, and is typically done for its own sake (i.e., the process is more important than any goals or endpoints). Recognized as a universal phenomenon, play is a legitimate right of childhood and should be part of all children’s life. Between 3% to 20% of young children’s time and energy is spent in play, and more so in a non-impoverished environment. Although play is an important arena in children’s life associated with immediate, short-term, and long-term term benefits, cultural factors influence children’s opportunities for free play in different ways. Over the last decade, there has been an ongoing reduction of playtime in favor of educational instructions, especially in modern and urban societies. Furthermore, parental concerns about safety sometimes limit children’s opportunities to engage in playful and creative activities. Along the same lines, the increase in commercial toys and technological developments by the toy industry has fostered more sedentary and less healthy play behaviors in children. Yet, play is essential to young children’s education and should not be abruptly minimized and segregated from learning. Not only does play help children develop pre-literacy skills, problem-solving skills, and concentration, but it also generates social learning experiences, and helps children to express possible stresses and problems.

Throughout the preschool years, young children engage in different forms of play, including social, parallel, object, sociodramatic, and locomotor play. The frequency and type of play vary according to children’s age, cognitive maturity, physical development, as well as the cultural context. For example, children with physical, intellectual, and/or language disabilities engage in play behaviors, yet they may experience delays in some forms of play and require more parental supervision than typically developing children.

Social play is usually the first form of play observed in young children. Social play is characterized by playful interactions with parents (up to age 2) and/or other children (from two years onwards). In spite of being around other children of their age, children between 2 to 3 years old commonly play next to each other without much interaction (i.e., parallel play). As their cognitive skills develop, including their ability to imagine, imitate, and understand others’ beliefs and intents, children start to engage in sociodramatic play. While interacting with same-age peers, children develop narrative thinking, problem-solving skills (e.g., when negotiating roles), and a general understanding of the building blocks of the story. Around the same time, physical/locomotor play also increases in frequency. Although locomotor play typically includes running and climbing, play fighting is common, especially among boys aged three to six. In contrast to popular belief, play fighting lacks intent to harm either emotionally or physically even though it can look like real fighting. In fact, during the primary school years, only about 1% of play-fighting turn into serious physical aggression. Nevertheless, the effects of such play are of special concern among children who display antisocial behavior and less empathic understanding, and therefore supervision is warranted.

In addition, to vary according to the child’s factors, the frequency, type, and play area are influenced by the cultural context. While there are universal features of play across cultures (e.g., traditional games and activities and gender-based play preferences), differences also exist. For instance, children who live in rural areas typically engage in more free play and have access to larger spaces for playing. In contrast, adult supervision in children’s play is more frequent in urban areas due to safety concerns. Along the same lines, cultures value and react differently to play. Some adults refrain from engaging in play as it represents a spontaneous activity for children while others promote the importance of structuring play to foster children’s cognitive, social and emotional development.

If play is associated with children’s academic and social development, teachers, parents, and therapists are encouraged to develop knowledge about the different techniques to help children develop their play-related skills. However, in order to come up with best practices, further research on the examination of high-quality play is warranted.

From the available literature on play, it is recommended to create play environments to stimulate and foster children’s learning. Depending on the type of play, researchers suggest providing toys that enhance children’s:

- motor coordination (e.g., challenging forms of climbing structure);

- creativity (e.g., building blocks, paint, clay, play dough);

- mathematic skills (e.g., board games “Chutes and Ladders” – estimation, counting, and numeral identification);

- language and reading skills (e.g., plastic letters, rhyming games, making shopping lists, bedtime story books, toys for pretending).

Other recommendations have been suggested in order to enhance literacy skills in children. Researchers suggest that setting up literacy-rich environments, such as a “real restaurant” with tables, menus, name tags, pencils, and notepads, are effective to increase children’s potential in early literacy development. Educators are also encouraged to adopt a whole child approach that targets not only literacy learning but also the child’s creativity, imagination, persistence, and positive attitudes in reading. Teachers and educators should also make a parallel between what can be learned from playful activities and the academic curriculum in order for children to understand that play allows them to practice and reinforce what is learned in class. However, educators should ensure that a curriculum based on playful learning includes activities that are perceived as playful by children themselves rather than only by the teachers. Most experts agree that a balanced approach consisting of periods of free play and structured/guided play should be favored. Indeed, adults are encouraged to give children space during playtime to enable the development of self-expression and independence in children with and without disabilities. Lastly, parents of children with socio-emotional difficulties are encouraged to receive play therapy training to develop empathic understanding and responsive involvement during playtime.[13]

Theories of Play

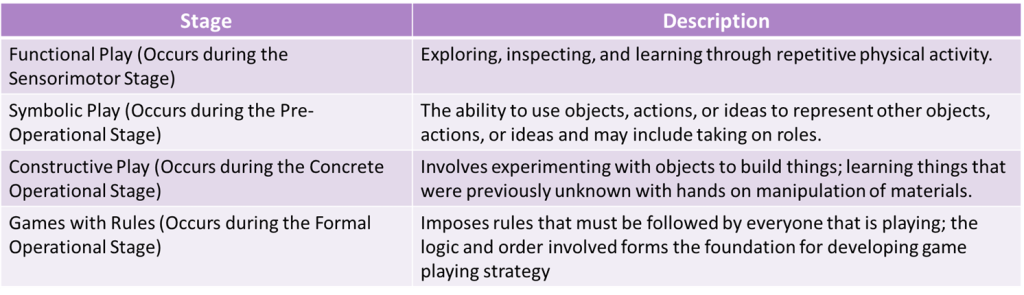

Freud saw play as a means for children to release pent-up emotions and to deal with emotionally distressing situations in a more secure environment. Piaget saw play as a way for children to develop their intellectual abilities (Dyer & Moneta, 2006). Piaget created stages of play that correspond with his stages of cognitive development. The stages are:

Piaget’s Stages of Play

While Freud, Piaget, and Vygotsky looked at play slightly differently, all three theorists saw play as providing positive outcomes for children.[14]

Parten’s Theory of Play

Parten (1932) observed two to five-year-old children and noted six types of play: Three labeled as non-social play (unoccupied, solitary, and onlooker) and three categorized as social play (parallel, associative, and cooperative). The table below describes each type of play. Younger children engage in non-social play more than those older; by age five associative and cooperative play are the most common forms of play (Dyer & Moneta, 2006).[19]

Parten’s Classification of Types of Play in Preschool Children

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION |

| Unoccupied Play | Children’s behavior seems more random and without a specific goal. This is the least common form of play. |

| Solitary Play | Children play by themselves, do not interact with others, nor are they engaging in similar activities as the children around them. |

| Onlooker Play | Children are observing other children playing. They may comment on the activities and even make suggestions but will not directly join the play. |

| Parallel Play | Children play alongside each other, using similar toys, but do not directly act with each other. |

| Associative Play | Children will interact with each other and share toys but are not working toward a common goal. |

| Cooperative Play | Children are interacting to achieve a common goal. Children may take on different tasks to reach that goal. |

Peer Relationships

Peer Relationships and their Influences on Social and Emotional Skills

Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many social skills that are valuable for the rest of life (Bukowski, Buhrmester, & Underwood, 2011). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as preschoolers engage in pretend play, they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those provided by their parents.[15]

Peer relationships are particularly important for children. Being accepted by other children is an important source of affirmation and self-esteem, but peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior).

With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is an important means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. For example, a boy who is not athletic may feel unworthy of his football-playing peers and revert to shy behavior, isolating himself and avoiding conversation. Conversely, an athlete who doesn’t “get” Shakespeare may feel embarrassed and avoid reading altogether. Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal)—which significantly influences a child’s outlook on the world. Each of these aspects of peer relationships require developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate the many ways that peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept.[16]

Imaginary Companions

An intriguing occurrence in early childhood is the emergence of imaginary companions. Researchers differ in how they define what qualifies as an imaginary companion. Some studies include only invisible characters that the child refers to in conversation or plays with for an extended period of time. Other researchers also include objects that the child personifies, such as a stuffed toy or doll, or characters the child impersonates every day. Estimates of the number of children who have imaginary companions varies greatly (from as little as 6% to as high as 65%) depending on what is included in the definition (Gleason, Sebanc, & Hartup, 2000). Little is known about why children create imaginary companions, and more than half of all companions have no obvious trigger in the child’s life (Masih, 1978). Imaginary companions are sometimes based on real people, characters from stories, or simply names the child has heard (Gleason, et. al., 2000). Imaginary companions often change over time. In their study, Gleason et al. (2000) found that 40% of the imaginary companions of the children they studied changed, such as developing superpowers, switching age, gender, or even dying, and 68% of the characteristics of the companion were acquired over time. This could reflect greater complexity in the child’s “creation” over time and/or a greater willingness to talk about their imaginary playmates. In addition, research suggests that contrary to the assumption that children with imaginary companions are compensating for poor social skills, several studies have found that these children are very sociable (Mauro, 1991; Singer & Singer, 1990; Gleason, 2002). However, studies have reported that children with imaginary companions are more likely to be first-borns or only-children (Masih, 1978; Gleason et al., 2000, Gleason, 2002). Although not all research has found a link between birth order and the incidence of imaginary playmates (Manosevitz, Prentice, & Wilson, 1973). Moreover, some studies have found little or no difference in the presence of imaginary companions and parental divorce (Gleason et al., 2000), number of people in the home, or the amount of time children are spending with real playmates (Masih, 1978; Gleason & Hohmann, 2006). Do children treat real friends differently? The answer appears to be not really. Young children view their relationship with their imaginary companion to be as supportive and nurturing as with their real friends. Gleason has suggested that this might suggest that children form a schema of what is a friend and use this same schema in their interactions with both types of friends (Gleason, et al., 2000; Gleason, 2002; Gleason & Hohmann, 2006).[17]

Some studies define imaginary companions as invisible characters that the child refers to in conversation or plays with for an extended period of time.[18]

Sociometric Peer Status and Popularity

Sociometric assessment measures attraction between members of a group, such as a classroom of students. In sociometric research children are asked to mention the three children they like to play with the most, and those they do not like to play with. The number of times a child is nominated for each of the two categories (like, do not like) is tabulated. Popular children receive many votes in the “like” category, and very few in the “do not like” category. In contrast, rejected children receive more unfavorable votes, and few favorable ones. Controversial children are mentioned frequently in each category, with several children liking them and several children placing them in the do not like category. Neglected children are rarely mentioned in either category while the average child has a few positive votes with very few negative ones (Asher & Hymel, 1981).

Most children want to be liked and accepted by their friends. Some popular children are nice and have good social skills. These popular-prosocial children tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. Popular-antisocial children may gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumors about others (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004). Rejected children are sometimes excluded because they are rejected-withdrawn. These children are shy and withdrawn and are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled (Boulton, 1999). Other rejected children are rejected-aggressive and are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. The aggressive-rejected children may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. Unfortunately, their fear of rejection only leads to behavior that brings further rejection from other children. Children who are not accepted are more likely to experience conflict, lack confidence, and have trouble adjusting (Klima & Repetti, 2008; Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2014).[23]

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION |

| Popular Children | Receive many votes in the “like” category, and very few in the “do not like” category. |

| Rejected Children | Receive more unfavorable votes and a few favorable ones. |

| Controversial Children | Mentioned frequently in each category, with several children liking them and several children placing them in the do not like category. |

| Neglected Children | Rarely mentioned in either category. |

| Average Children | Have a few positive votes with very few negative votes. |

| Popular- Prosocial Children | Are nice and have good social skills; tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. |

| Popular-Antisocial Children | May gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumors about others. |

| Rejected -Withdrawn Children | Are shy and withdrawn and are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled. |

| Rejected-Aggressive Children | Are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. They may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. |

Sociometric Peer Status.[19]

Long-Term Outcomes of Popularity

Childhood popularity researcher Mitch Prinstein has found that likability in childhood leads to positive outcomes throughout one’s life (as cited in Reid, 2017). Adults who were accepted in childhood have stronger marriages and work relationships, earn more money, and have better health outcomes than those who were unpopular. Furthermore, those who were unpopular as children, experienced greater anxiety, depression, substance use, obesity, physical health problems, and suicide. Prinstein found that a significant consequence of unpopularity was that children were denied opportunities to build their social skills and negotiate complex interactions, thus contributing to their continued unpopularity. Further, biological effects can occur due to unpopularity, as social rejection can activate genes that lead to an inflammatory response.[20]

Bullying

According to Stopbullying.gov (2018), a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, bullying is defined as unwanted, aggressive behavior among school-aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. Further, the aggressive behavior happens more than once or has the potential to be repeated.

To be considered bullying, the behavior must be aggressive and include:

- An Imbalance of Power: Kids who bully use their power—such as physical strength, access to embarrassing information, or popularity—to control or harm others. Power imbalances can change over time and in different situations, even if they involve the same people.

- Repetition: Bullying behaviors happen more than once or have the potential to happen more than once. [21]

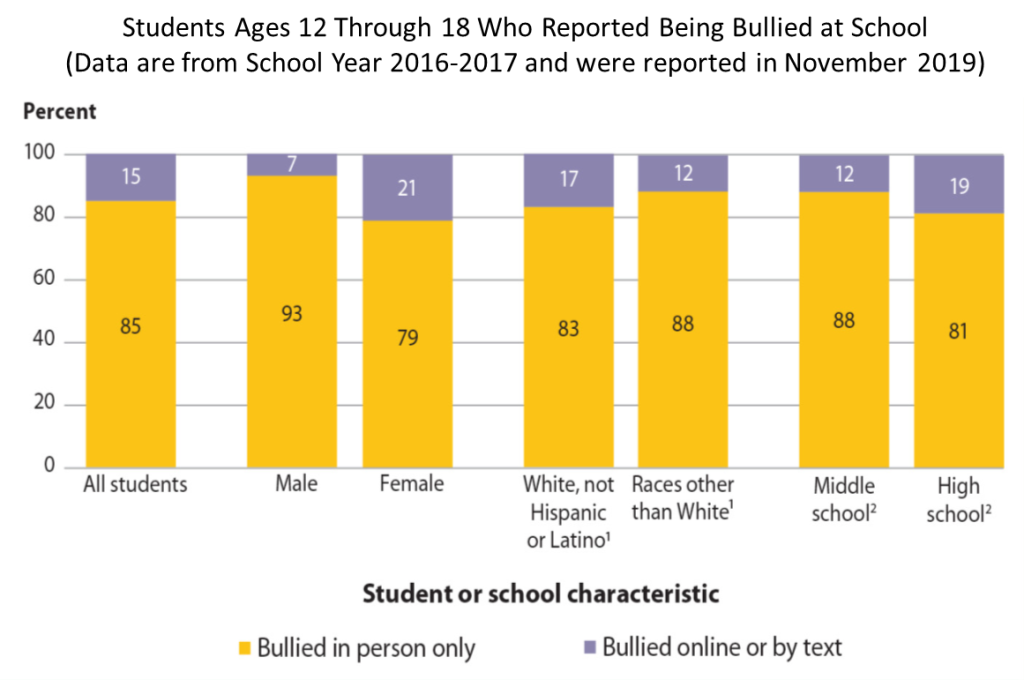

The data used in the above bar graph is from a 2017 School Crime Supplement (SCS), a nationally representative sample survey of students ages 12 through 18 enrolled in public or private school for all or part of the school year (not homeschooled for all of the school year).[22]

The negative treatment typical in bullying is the attempt to inflict harm, injury, or humiliation, and bullying can include physical or verbal attacks. However, bullying doesn’t have to be physical or verbal, it can be psychological. Research finds gender differences in how girls and boys bully others (American Psychological Association, 2010; Olweus, 1993). Boys tend to engage in direct, physical aggression such as physically harming others. Girls tend to engage in indirect, social forms of aggression such as spreading rumors, ignoring, or socially isolating others. Based on what you have learned about child development and social roles, why do you think boys and girls display different types of bullying behavior? Bullying involves three parties: the bully, the victim, and witnesses or bystanders. The act of bullying involves an imbalance of power with the bully holding more power—physically, emotionally, and/or socially over the victim. The experience of bullying can be positive for the bully, who may enjoy a boost to self-esteem. However, there are several negative consequences of bullying for the victim, and also for the bystanders. How do you think bullying negatively impacts adolescents? Being the victim of bullying is associated with decreased mental health, including experiencing anxiety and depression (APA, 2010). Victims of bullying may underperform in schoolwork (Bowen, 2011). Bullying also can result in the victim dying by suicide (APA, 2010). How might bullying negatively affect witnesses?

There are different types of bullying[23]

Types of Bullying

Verbal bullying: saying or writing mean things. Verbal bullying includes:

- Teasing

- Name-calling

- Inappropriate sexual comments

- Taunting

- Threatening to cause harm

Social bullying: sometimes referred to as relational bullying, involves hurting someone’s reputation or relationships. Social bullying includes:

- Leaving someone out on purpose

- Telling other children not to be friends with someone

- Spreading rumors about someone

- Embarrassing someone in public

Physical bullying: hurting a person’s body or possessions. Physical bullying includes:

- Hitting, kicking, or pinching

- Spitting

- Tripping or pushing

- Taking or breaking someone’s things

- Making mean or rude hand gestures

Bullying can occur during or after school hours. While most reported bullying happens in the school building, a significant percentage also happens in places like on the playground or the bus. It can also happen travelling to or from school, in the youth’s neighborhood, or on the Internet.

Cyberbullying

With widely available mobile technology and social networking media, a new form of bullying has emerged: cyberbullying. Cyberbullying, like bullying, is repeated behavior that is intended to cause psychological or emotional harm to another person. What is unique about cyberbullying is that it is typically covert, concealed, done in private, and the bully can remain anonymous. This anonymity gives the bully power, and the victim may feel helpless, unable to escape the harassment, and unable to retaliate (Spears, Slee, Owens, & Johnson, 2009). About one in three middle and high school students report that they have experienced cyberbullying (Patchin, 2016; Patchin, 2019), with some studies indicating that nearly three in five teens have experienced some type of online abusive behavior such as non-repeated name-calling or being sent unsolicited links or images (Anderson, 2018).

Cyberbullying can take many forms, including harassing a victim by spreading rumors, creating a website defaming the victim, threatening the victim, or teasing the victim (Spears et al., 2009). Overall, LGBTQ youth are targeted at a higher rate than heterosexual and cisgender youth, and members of minority populations overall are more likely to be cyberbullying victims (Hinjuda & Patchin, 2020). In terms of gender, experiences vary in terms of both the prevalence and types of cyberbullying experienced and perpetrated. In cyberbullying, it is more common for girls to be the bullies and victims. Interestingly, girls who become cyberbullies often have been the victims of cyberbullying at one time (Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2009). Girls were more likely to say someone spread rumors about them online while boys were more likely to say that someone threatened to hurt them online (Patchin, 2019). The effects of cyberbullying are just as harmful as traditional bullying and include the victim feeling frustration, anger, sadness, helplessness, powerlessness, and fear. Victims will also experience lower self-esteem (Hoff & Mitchell, 2009; Spears et al., 2009). Furthermore, recent research suggests that both cyberbullying victims and perpetrators are more likely to experience suicidal ideation, and they are more likely to attempt suicide than individuals who have no experience with cyberbullying (John, 2019). Cyberbullying is a form of aggression and, depending on the messages and methods, can be considered harassment, stalking, or assault—all subject to prosecution. Finally, while much of the concern and research regarding cyberbullying centers on adolescents, adults (particularly college students) are frequent victims and perpetrators. What features of technology make cyberbullying easier and perhaps more accessible to young adults? What can parents, teachers, and social networking websites do to prevent cyberbullying? [24]

Online chatting is one place for cyberbullying. [25]

Children Who Are at Risk of Being Bullied

Although there is not one single personality profile for who becomes a bully and who becomes a victim of bullying (APA, 2010), researchers have identified some patterns in children who are at a greater risk of being bullied (Olweus, 1993):

- Children who are emotionally reactive are at a greater risk for being bullied. Bullies may be attracted to children who get upset easily because the bully can quickly get an emotional reaction from them.

- Children who are different from others are likely to be targeted for bullying. Children who are overweight, cognitively impaired, or racially or ethnically different from their peer group may be at higher risk.

- Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender teens are at very high risk of being bullied and hurt due to their sexual orientation. [26]

Signs a Child is Being Bullied

Look for changes in the child. However, be aware that not all children who are bullied exhibit warning signs. Some signs that may point to a bullying problem are:

- Unexplainable injuries

- Lost or destroyed clothing, books, electronics, or jewelry

- Frequent headaches or stomach aches, feeling sick or faking illness

- Changes in eating habits, like suddenly skipping meals or binge eating. Kids may come home from school hungry because they did not eat lunch.

- Difficulty sleeping or frequent nightmares[27]

Many of the warning signs that cyberbullying is occurring happen around a child’s use of their device. Some of the warning signs that a child may be involved in cyberbullying are:

- A child exhibits emotional responses (laughter, anger, upset) to what is happening on their device.

- A child hides their screen or device when others are near and avoids discussion about what they are doing on their device.

- Social media accounts are shut down or new ones appear.

- A child starts to avoid social situations, even those that were enjoyed in the past.

- A child becomes withdrawn or depressed or loses interest in people and activities.[28]

How to Prevent Bullying at School

The research on bullying prevention programming has increased considerably over the past 2 decades, which is likely due in part to the growing awareness of bullying as a public health problem that impacts individual youth as well as the broader social environment. Furthermore, the enactment of bullying-related laws and policies in all 50 states has drawn increased focus on prevention programming. In fact, many state policies require some type of professional development for staff or prevention programming related to bullying (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2015; Stuart-Cassel et al., 2011).[29]

Training school staff and students to prevent and address bullying can help sustain bullying prevention efforts over time. While there are no federal mandates for bullying curricula or staff training, schools don’t always need formal programs to help students learn about bullying prevention, and can incorporate the topic of bullying prevention in lessons and activities. Examples of activities to teach about bullying include:

- Internet or library research, such as looking up types of bullying, how to prevent it, and how kids should respond

- Presentations, such as a speech or role-play on stopping bullying

- Discussions about topics like reporting bullying

- Creative writing, such as a poem speaking out against bullying or a story or skit teaching bystanders how to help

- Artistic works, such as a collage about respect or the effects of bullying

- Classroom meetings to talk about peer relations

Schools may choose to implement formal evidence-based programs or curricula. Many evaluated programs that address bullying are designed for use in elementary and middle schools. Fewer programs exist for high schools and non-school settings. There are many considerations in selecting a program, including the school’s demographics, capacity, and resources.[30]

One such evidenced based program/curricula, Bully Prevention in Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (BP-PBIS) is designed (a) to define and teach the concept of “being respectful” to all students in a school, (b) to teach all students a three-step response ((stop, walk, talk) (Indicating through words and gesture to stop, walk away if the problem continues, and finally talking to an adult if the issue is still not resolved)) that minimizes potential social reinforcement when they encounter disrespectful behavior, (c) to precorrect the three-step response prior to entering activities likely to include problematic behavior, (d) to teach an appropriate reply when the three-step response is used, and (e) to train staff on a universal strategy for responding when students report incidents of problem behavior.[31]

To ensure that bullying prevention efforts are successful, all school staff need to be trained on what bullying is, what the school’s policies and rules are, and how to enforce the rules. Training may take many forms: staff meetings, one-day training sessions, and teaching through modeling preferred behavior. Schools may choose any combination of these training options based on available funding, staff resources, and time.

Training can be successful when staff are engaged in developing messages and content, and when they feel that their voices are heard. Learning should be relevant to their roles and responsibilities to help build buy-in.[32]

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Committee on the Science of Children Birth to Age 8: Deepening and Broadening the Foundation for Success; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Institute of Medicine; National Research Council; Allen LR, Kelly BB, editors. Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 Jul 23. 4, Child Development and Early Learning. Licensed under Public Domain. ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Malle, B. (2020). Theory of mind. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a8wpytg3 is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- Image retrieved from pixabay.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Malle, B. (2020). Theory of mind. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a8wpytg3 is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- Malle, B. (2020). Theory of mind. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a8wpytg3 is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 ↵

- Malle, B. (2020). Theory of mind. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a8wpytg3 is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Senju A. Spontaneous theory of mind and its absence in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscientist. 2012 Apr;18(2):108-13. doi: 10.1177/1073858410397208. Epub 2011 May 23. PMID: 21609942; PMCID: PMC3796729. Licensed under Public domain. ↵

- Schwartz Offek E, Segal O. Comparing Theory of Mind Development in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Developmental Language Disorder, and Typical Development. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022 Oct 14;18:2349-2359. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S331988. PMID: 36268263; PMCID: PMC9578470. Licensed under Public domain. ↵

- Images retrieved from Pixabay.com are licensed under CC0. ↵

- Child and Adolescent Psychology Lumen Learning licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Play: Synthesis. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Smith PK, topic ed. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play/synthesis. Updated June 2013. Accessed July 29, 2020. Used with permission. ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0[19] Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0[ ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Child and Adolescent Psychology Lumen Learning licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0[23] Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Image retrieved from Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0. ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Public Domain: No Known Copyright ↵

- Text and table from Data Point. U.S. Department of Education: Electronic Bullying: Online and by Text. Published November 2019. Public Domain. ↵

- Image retrieved from Pixabay is licensed under CC0. ↵

- Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License v4.0 ↵

- Images retrieved from Pixabay.com are licensed under CC0. ↵

- Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License v4.0 ↵

- stopbullying.gov a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Licensed under public domain. ↵

- stopbullying.gov a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Licensed under public domain. ↵

- Committee on the Biological and Psychosocial Effects of Peer Victimization: Lessons for Bullying Prevention; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Law and Justice; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Rivara F, Le Menestrel S, editors. Preventing Bullying Through Science, Policy, and Practice. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Sep 14. 5, Preventive Interventions. Licensed under public domain. ↵

- From stopbullying.gov. A federal government website managed by the U.S Department Of Health and Human Services. Licensed under public domain. (adapted by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Ross SW, Horner RH. Bully prevention in positive behavior support. J Appl Behav Anal. 2009 Winter;42(4):747-59. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-747. PMID: 20514181; PMCID: PMC2791686. Licensed under public domain. ↵

- From stopbullying.gov. A federal government website managed by the U.S Department Of Health and Human Services. Licensed under public domain. ↵

a social-cognitive skill that involves the ability to think about mental states, both your own and those of others.

a theoretical construct referring to a suite of abilities that enable coordinated, collaborative interactions. A core idea of shared intentionality is that such interactions are made possible by the human motivation to share mental states with others.

a type of task used in theory of mind studies in which children must infer that another person does not possess knowledge that they possess.

a goal is the end state toward which a human or nonhuman animal is striving: the purpose of an activity or endeavor.

to select behaviors and beliefs that are in the service of attaining the goal

an observer repeats the behavior that is performed by a model

the rhythmic coordination of speech and movement that occurs non-consciously, both in and between individuals during communication

type of cells in the brains of certain animals (including humans) that responds in the same way to a given action (e.g., grasping an object) whether the animal performs the action itself or sees another animal (not necessarily of the same species) perform the action. This phenomenon is known as mirror imaging.

responses to perceived signals of other people's emotions are elicited in an involuntarily way.

attention overtly focused by two or more people on the same object, person, or action at the same time, with each being aware of the other’s interest.

visual perspective taking is the need to consider what another person can see from a different point of view.

using one's own mental states and assigning them to others in order to predict how they will behave

a defense mechanism in which unpleasant or unacceptable impulses, stressors, ideas, affects, or responsibilities are attributed to others.

a significant or embarrassing error or mistake.

activities that appear to be freely sought and pursued solely for the sake of individual or group enjoyment. Play is a cultural universal and typically regarded as an important mechanism in children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development.

the systematic use of a theoretical model to establish an interpersonal process wherein trained play therapists use the therapeutic powers of play to help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties and achieve optimal growth and development.

any process that involves reciprocal stimulation or response between two or more individuals.

interpersonal relationships established and developed during social interactions among peers or individuals with similar levels of psychological development

the act of contrasting one's own life with the lives of other people as they are publicly represented.

a fictitious person, animal, or object created by a child or adolescent.

the measurement of interpersonal relationships in a social group. Socio-metric measurement or assessment methods provide information about an individual's social status, which is their social standing within a group. School-based sociometric assessment focuses on a child's relationships with peers.

persistent threatening and aggressive physical behavior or verbal abuse directed toward other people, especially those who are younger, smaller, weaker, or in some other situation of relative disadvantage

a strategy to prevent challenging behaviors from occurring