1 Introduction to Infant and Child Development

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 1, you should be better equipped to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development

- Understand the theoretical questions posed by developmental psychologists.

- Explain the concept of a theory.

- Compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Why Study Infants and Children from a Psychological Perspective?

From the perspective of a parent, seeing your child develop can be both rewarding and challenging. Hearing your child say his or her first word, or watching your child take their first steps are memories a parent will never forget. However, why should the development of infants and children be of interest from a psychological perspective? What information can be gained from such study, and how can this information be used to benefit others?[1]

Two of the key goals involved in the study of infant and child development focus on:

- Describing change – many of the studies we will examine simply involve the first step in investigation, which is description. Arnold Gesell’s study on infant motor skills, for example.

- Explaining change – Theories provide explanations for why we change over time. For example, Erikson offers an explanation about why a two-year-old might be temperamental.

Think about how you were 5, 10, or even 15 years ago. In what ways have you changed? In what ways have you remained the same? You have probably changed physically; perhaps you have grown taller and become heavier. But you may have also experienced changes in the way you think and solve problems. [2]

Development is multidimensional and as we grow, we change across three general domains or dimensions, the physical, the cognitive, and the social/emotional.

The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness. The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language. The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.[3]

Emotional, social, and cognitive change is noticeable when we compare how 1-year-olds, 3-year-olds, and 6-year-olds think and reason. Their thoughts about others and the world are quite different. Consider play for instance. The typical 1-year-old will play alone with little interaction, whereas the 3-year-old will play alongside others, but not play together, and the 6-year-old plays cooperatively with others often with a shared goal. [4]

It is important to understand that all three domains influence each other, and that change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains. In addition, development in each domain is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change and many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient and able to overcome adversity.

Finally, Development is multi-contextual. We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us, and it is important to understand that physical growth, behavior, motivation, emotion, and choice are all part of a bigger picture.[5]

Periods of Development

Think about what periods of development that you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers. Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through two years)

Early Childhood (3 to 5 years)

Middle Childhood (6 to 11 years)

Adolescence (12 years to adulthood)

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adolescence that will be explored in this book. So while both an 8 month old and an 8 year old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The first two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. And children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences.[6]

Theoretical Questions in Development

Nature and Nurture

Why are you the way you are? As you consider some of your features (height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc.), ask yourself whether these features are a result of heredity or environmental factors, or both. Chances are, you can see the ways in which both heredity and environmental factors (such as lifestyle, diet, and so on) have contributed to these features. For decades, scholars have carried on the "nature/nurture" debate. For any one feature, those on the side of nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

Continuity versus Discontinuity

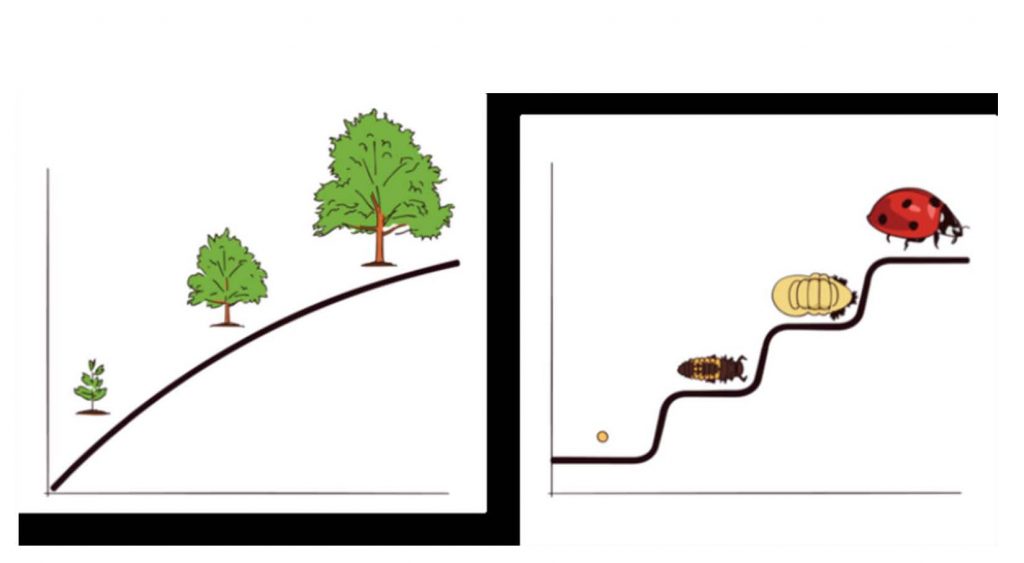

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

Continuous versus Discontinuous Development

A graphic image describing continuous and discontinuous stage development. The tree represents continuous development, while the ladybug represents discontinuous development.[7]

Active versus Passive

How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their own development. Piaget, for instance believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process.

Stability versus Change

How similar are you to how you were as a child? Were you always as out-going or reserved as you are now? Some theorists argue that the personality traits of adults are rooted in the behavioral and emotional tendencies of the infant and young child. Others disagree and believe that these initial tendencies are modified by social and cultural forces over time.

Investment in Early Childhood Development Lays the Foundation for a Prosperous and Sustainable Society[8]

The first years of life are important, because what happens in early childhood can matter for a lifetime. Science shows us what children must have, and what they need to be protected from, in order to promote their healthy development. Stable, responsive, nurturing relationships and rich learning experiences in the earliest years provide lifelong benefits for learning, behavior and both physical and mental health. In contrast, research on the biology of stress in early childhood shows how chronic stress caused by major adversity, such as extreme poverty, abuse or neglect, can weaken developing brain architecture and permanently set the body’s stress response system on high alert, thereby increasing the risk for a range of chronic diseases.

The following basic concepts established over decades of neuroscience and behavioral research, help illustrate why healthy child development from birth to five years provides a foundation for a prosperous and sustainable society.

Brains are built over time, from the bottom up. The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process that begins before birth and continues into adulthood. Early experiences affect the quality of that architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for the learning, health and behavior that follow. In the first few years of life, 700 new neural connections (called synapses) are formed every second. After this period of rapid proliferation, these connections are reduced through a process called pruning, so that brain circuits become more efficient. Sensory pathways, like those for basic vision and hearing, are the first to develop, followed by early language skills and later by higher cognitive functions. Connections proliferate and prune in a prescribed order, with later, more complex brain circuits built upon earlier, simpler circuits.

The interactive influences of genes and experience shape the developing brain. Scientists now know a major ingredient in this developmental process is what has been called a “serve and return” relationship between children and their parents and other caregivers in the family or community. Young children naturally reach out for interaction through babbling, facial expressions and gestures, and adults respond with similar kinds of vocalizing and gesturing back at them. In the absence of such responses – or if the responses are unreliable or inappropriate – the brain’s architecture does not form as expected, which can lead to disparities in learning and behavior.

The brain’s capacity for change decreases with age. It is most flexible, or “plastic,” early in life to accommodate a wide range of environments and interactions, but as the maturing brain becomes more specialized to assume more complex functions, it is less capable of reorganizing and adapting to new or unexpected challenges. For example, by the end of the first year, the parts of the brain that differentiate sounds are becoming specialized according to the language the baby has heard. At the same time, the brain is already starting to lose the ability to recognize different sounds found in other languages. Although the “windows” for complex language learning and other skills remain open, these brain circuits become increasingly difficult to alter over time. Early plasticity means it’s easier and more effective to influence a baby’s developing brain architecture than to rewire parts of its circuitry during adolescence and the adult years.

Cognitive, emotional, and social capacities are inextricably intertwined throughout the life course. The brain is a highly integrated organ, and its multiple functions operate in a richly coordinated fashion. Emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar that make up the foundation of human development. The emotional and physical health, social skills and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important prerequisites for success in school and, later, in the workplace and community.

Although learning how to cope with adversity is an important part of healthy child development, excessive or prolonged stress can be toxic to the developing brain. When we are threatened, our bodies activate a variety of physiological responses, including increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones, such as cortisol. When a young child is protected by supportive relationships with adults, he learns how to adapt to everyday challenges and his stress response system returns to baseline. Scientists call this positive stress. Tolerable stress occurs when more serious difficulties, such as the loss of a loved one, a natural disaster, or a frightening injury, are buffered by caring adults who help the child adapt, thereby mitigating the potentially damaging effects of abnormal levels of stress hormones. When strong, frequent or prolonged adverse experiences, such as extreme poverty or repeated abuse, are experienced without adult support, stress becomes toxic and disrupts developing brain circuits. Toxic stress experienced early in life can also have a cumulative toll on learning capacity as well as physical and mental health. The more adverse experiences in childhood, the greater the likelihood of developmental difficulties and other problems. Adults with more adverse experiences in early childhood are also more likely to have chronic health problems, including alcoholism, depression, heart disease and diabetes.

Early intervention can prevent the consequences of early adversity. Research shows that later interventions are likely to be less successful – and in some cases are ineffective. For example, when children who experienced extreme neglect were placed in responsive foster care families before age two, their IQs increased more substantially and their brain activity and attachment relationships were more likely to become normal than if they were placed after the age of two. While there is no “magic age” for intervention, it is clear that, in most cases, intervening as early as possible is significantly more effective than waiting.

Stable, caring relationships are essential for healthy development. Children develop in an environment of relationships that begin in the home and include extended family members, early care and education providers, and other members of the community. Studies show that toddlers who have secure, trusting relationships with their parents or non-parent caregivers experience minimal stress hormone activation when frightened by a strange event, and those who have insecure relationships experience a significant activation of the stress response system. Numerous scientific studies support the conclusion that providing supportive, responsive relationships as early in life as possible can prevent or reverse the damaging effects of toxic stress.

Conclusion

The basic principles of neuroscience indicate that providing supportive conditions for early childhood development is more effective and less costly than attempting to address the consequences of early adversity later. To this end, a balanced approach to emotional, social, cognitive and language development will best prepare all children for success in school and later in the workplace and community. For children experiencing toxic stress, specialized interventions – as early as possible – are needed to target the cause of the stress and protect the child from its consequences.

From pregnancy through early childhood, all of the environments in which children live and learn, and the quality of their relationships with adults and caregivers, have a significant impact on their cognitive, emotional and social development. A wide range of policies, including those directed toward early care and education, primary health care, child protective services, adult mental health, and family economic supports, among many others, can promote the safe, supportive environments and stable, caring relationships that children need.

Theories of Development

What is a Theory?

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are simply an explanation of something and can be valuable tools for understanding human behavior. In fact, developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.[9]

Theories help guide and interpret research findings by providing researchers with help putting together various research findings. Think of theories as a story that is used to both explain behaviors and to guide research. Each time a researcher conducts an experiment to test the validity of a theory another page is being added to the story. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Historical Theories of Development

John Locke(1632-1704)[10]

John Locke, a British philosopher, refuted the idea of innate knowledge and instead proposed that children are largely shaped by their social environments, especially their education as adults teach them important knowledge. He believed that through education a child learns socialization, or what is needed to be an appropriate member of society. Locke advocated thinking of a child’s mind as a tabula rasa or blank slate, and whatever comes into the child’s mind comes from the environment. Locke emphasized that the environment is especially powerful in the child’s early life because he considered the mind the most pliable then. Locke indicated that the environment exerts its effects through associations between thoughts and feelings, behavioral repetition, imitation, and rewards and punishments (Crain, 2005). Locke’s ideas laid the groundwork for the behavioral perspective and subsequent learning theories of Pavlov, Skinner and Bandura.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)[11]

Like Locke, Rousseau also believed that children were not just little adults. However, he did not believe they were blank slates, but instead developed according to a natural plan which unfolded in different stages (Crain, 2005). He did not believe in teaching them the correct way to think but believed children should be allowed to think by themselves according to their own ways and an inner, biological timetable. This focus on biological maturation resulted in Rousseau being considered the father of developmental psychology. Followers of Rousseau’s developmental perspective include Gesell, Montessori, and Piaget.[12]

Contemporary Theories of Development

Psychoanalytic Theories

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and Psychoanalytic Theory[13]

While sometimes controversial, Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

While sometimes controversial, Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resiliency in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Freud’s Background

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was a Viennese M. D. who was trained in neurology and asked to work with patients suffering from hysteria, a conditioned marked my uncontrollable emotional outbursts, fears and anxiety that had puzzled physicians for centuries. He was also asked to work with women who suffered from physical symptoms and forms of paralysis which had no organic causes. During that time, many people believed that certain individuals were genetically inferior and thus more susceptible to mental illness. Women were thought to be genetically inferior and thus prone to illnesses such as hysteria (which had previously been attributed to a detached womb which was traveling around in the body).

However, after World War I, many soldiers came home with problems similar to hysteria. This called into questions the idea of genetic inferiority as a cause of mental illness. Freud began working with hysterical patients and discovered that when they began to talk about some of their life experiences, particularly those that took place in early childhood, their symptoms disappeared. This led him to suggest the first purely psychological explanation for physical problems and mental illness. What he proposed was that unconscious motives and desires, fears and anxieties drive our actions. When upsetting memories or thoughts begin to find their way into our consciousness, we develop defenses to shield us from these painful realities. These defense mechanisms include denying a reality, repressing or pushing away painful thoughts, rationalization or finding a seemingly logical explanation for circumstances, projecting or attributing our feelings to someone else, or outwardly opposing something we inwardly desire (called reaction formation). Freud believed that many mental illnesses are a result of a person’s inability to accept reality. Freud emphasized the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our personality and behavior. In our natural state, we are biological beings. We are driven primarily by instincts. During childhood, however, we begin to become social beings as we learn how to manage our instincts and transform them into socially acceptable behaviors. The type of parenting the child receives has a very power impact on the child’s personality development. We will explore this idea further in our discussion of psychosexual development.

Freud’s Theory of the Mind

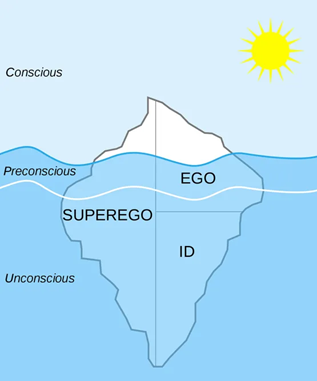

Freud believed that most of our mental processes, motivations and desires are outside of our awareness. Our consciousness, that of which we are aware, represents only the tip of the iceberg that comprises our mental state. The preconscious represents that which can easily be called into the conscious mind. During development, our motivations and desires are gradually pushed into the unconscious because raw desires are often unacceptable in society.

Freud’s Theory of the Self

As adults, our personality or self consists of three main parts: the id, the ego and the superego. The id is the part of the self with which we are born. It consists of the biologically driven self and includes our instincts and drives. It is the part of us that wants immediate gratification. Later in life, it comes to house our deepest, often unacceptable desires such as sex and aggression. It operates under the pleasure principle which means that the criteria for determining whether something is good or bad is whether it feels good or bad. An infant is all id. The ego is the part of the self that develops as we learn that there are limits on what is acceptable to do and that often, we must wait to have our needs satisfied. This part of the self is realistic and reasonable. It knows how to make compromises. It operates under the reality principle or the recognition that sometimes need gratification must be postponed for practical reasons. It acts as a mediator between the id and the superego and is viewed as the healthiest part of the self.[14]

The superego’s function is to control the id’s impulses, especially those which society forbids, such as sex and aggression. It also has the function of persuading the ego to turn to moralistic goals rather than simply realistic ones and to strive for perfection.

The superego consists of two systems: The conscience and the ideal self. The conscience can punish the ego through causing feelings of guilt. For example, if the ego gives in to the id’s demands, the superego may make the person feel bad through guilt.

The ideal self (or ego-ideal) is an imaginary picture of how you ought to be, and represents career aspirations, how to treat other people, and how to behave as a member of society.

Behavior which falls short of the ideal self may be punished by the superego through guilt. The super-ego can also reward us through the ideal self when we behave ‘properly’ by making us feel proud. If a person’s ideal self is too high a standard, then whatever the person does will represent failure. The ideal self and conscience are largely determined in childhood from parental values and how you were brought up.[15]

Freud’s Levels of Consciousness in Relation to the Id, Ego, and Superego

Freud’s description of personality shows that the ego operates primarily at the conscious level, but also operates somewhat at both the preconscious and unconscious level as does the superego. However, the superego operates mostly at the unconscious level whereas the id totally functions at the unconscious level.[16]

Defense mechanisms emerge to help a person distort reality so that the truth is less painful. Defense mechanisms include repression which means to push the painful thoughts out of consciousness (in other words, think about something else). Denial is basically not accepting the truth or lying to the self. Thoughts such as “it won’t happen to me” or “you’re not leaving” or “I don’t have a problem with alcohol” are examples. Regression refers to going back to a time when the world felt like a safer place, perhaps reverting to one’s childhood. This is less common than the first two defense mechanisms. Sublimation involves transforming unacceptable urges into more socially acceptable behaviors. For example, a teenager who experiences strong sexual urges uses exercise to redirect those urges into more socially acceptable behavior. Displacement involves taking out frustrations on to a safer target. A person who is angry at a boss may take out their frustration at others when driving home or at a spouse upon arrival. Projection is a defense mechanism in which a person attributes their unacceptable thoughts onto others. If someone is frightened, for example, he or she accuses someone else of being afraid. Finally, reaction formation is a defense mechanism in which a person outwardly opposes something they inwardly desire, but that they find unacceptable. An example of this might be homophobia or a strong hatred and fear of homosexuality. This is a partial listing of defense mechanisms suggested by Freud. If the ego is strong, the individual is realistic and accepting of reality and remains more logical, objective, and reasonable. Building ego strength is a major goal of psychoanalysis (Freudian psychotherapy). So, for Freud, having a big ego is a good thing because it does not refer to being arrogant, it refers to being able to accept reality.

The superego is the part of the self that develops as we learn the rules, standards, and values of society. This part of the self takes into account the moral guidelines that are a part of our culture. It is a rule-governed part of the self that operates under a sense of guilt (guilt is a social emotion-it is a feeling that others think less of you or believe you to be wrong). If a person violates the superego, he or she feels guilty. The superego is useful but can be too strong; in this case, a person might feel overly anxious and guilty about circumstances over which they had no control. Such a person may experience high levels of stress and inhibition that keeps them from living well. The id is inborn, but the ego and superego develop during the course of our early interactions with others. These interactions occur against a backdrop of learning to resolve early biological and social challenges and play a key role in our personality development.

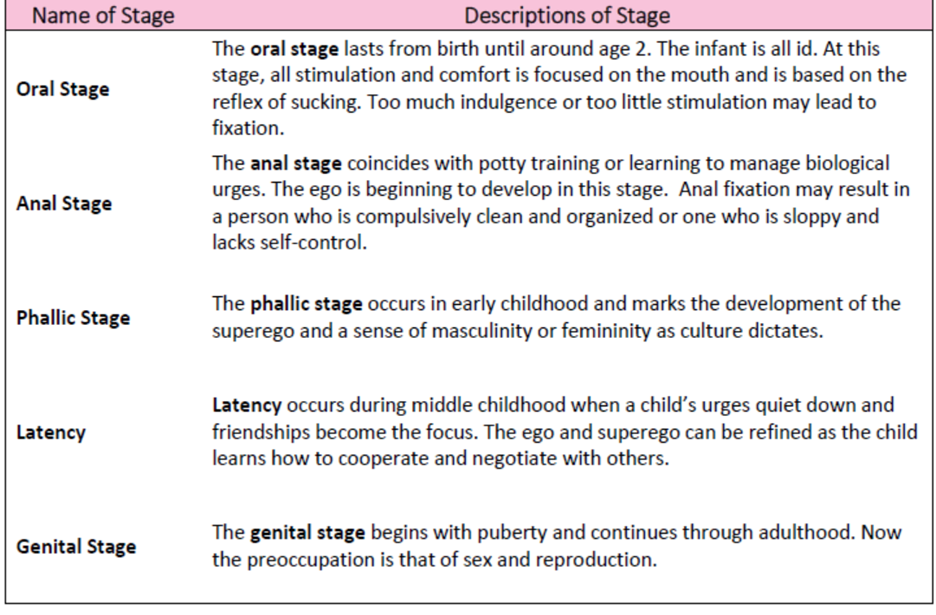

Psychosexual Stages

Freud’s psychosexual stages of development are presented in the table below. At any of these stages, the child might become “stuck” or fixated if a caregiver either overly indulges or neglects the child’s needs. A fixated adult will continue to try and resolve this later in life. Examples of fixation are given after the presentation of each stage.

Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

For about the first year of life, the infant is in the oral stage of psychosexual development. The infant meets his or her needs primarily through oral gratification. A baby wishes to suck or chew on any object that comes close to the mouth. Babies explore the world through the mouth and find comfort and stimulation as well. Psychologically, the infant is all id. The infant seeks immediate gratification of needs such as comfort, warmth, food, and stimulation. If the caregiver meets oral needs consistently, the child will move away from this stage and progress further. However, if the caregiver is inconsistent or neglectful, the person may remain stuck in the oral stage. As an adult, the person might not feel good unless involved in some oral activity such as eating, drinking, smoking, nail-biting, or compulsive talking. These actions bring comfort and security when the person feels insecure, afraid, or bored.

For about the first year of life, the infant is in the oral stage of psychosexual development. The infant meets his or her needs primarily through oral gratification. A baby wishes to suck or chew on any object that comes close to the mouth. Babies explore the world through the mouth and find comfort and stimulation as well. Psychologically, the infant is all id. The infant seeks immediate gratification of needs such as comfort, warmth, food, and stimulation. If the caregiver meets oral needs consistently, the child will move away from this stage and progress further. However, if the caregiver is inconsistent or neglectful, the person may remain stuck in the oral stage. As an adult, the person might not feel good unless involved in some oral activity such as eating, drinking, smoking, nail-biting, or compulsive talking. These actions bring comfort and security when the person feels insecure, afraid, or bored.

During the anal stage which coincides with toddlerhood or mobility and potty-training, the child is taught that some urges must be contained, and some actions postponed. There are rules about certain functions and when and where they are to be carried out. The child is learning a sense of self-control. The ego is being developed. If the caregiver is extremely controlling about potty training (stands over the child waiting for the smallest indication that the child might need to go to the potty and immediately scoops the child up and places him on the potty chair, for example), the child may grow up fearing losing control. He may become fixated in this stage or “anal retentive”-fearful of letting go. Such a person might be extremely neat and clean, organized, reliable, and controlling of others. If the caregiver neglects to teach the child to control urges, he may grow up to be “anal expulsive” or an adult who is messy, irresponsible, and disorganized.

The Phallic stage occurs during the preschool years (ages 3-5) when the child has a new biological challenge to face. Freud believed that the child becomes sexually attracted to his or her opposite sexed parent. Boys experience the “Oedipal Complex” in which they become sexually attracted to their mothers but realize that Father is in the way. He is much more powerful. For a while, the boy fears that if he pursues his mother, father may castrate him (castration anxiety). So rather than risking losing his penis, he gives up his affections for his mother and instead learns to become more like his father, imitating his actions and mannerisms and thereby learns the role of males in his society. From this experience, the boy learns a sense of masculinity. He also learns what society thinks he should do and experiences guilt if he does not comply. In this way, the superego develops. If he does not resolve this successfully, he may become a “phallic male” or a man who constantly tries to prove his masculinity (about which he is insecure) by seducing women and beating up men! A little girl experiences the “Electra Complex” in which she develops an attraction for her father but realizes that she cannot compete with mother and so gives up that affection and learns to become more like her mother. This is not without some regret, however. Freud believed that the girl feels inferior because she does not have a penis (experiences “penis envy”). But she must resign herself to the fact that she is female and will just have to accept her inferior role in society as a female. However, if she does not resolve this conflict successfully, she may have a weak sense of femininity and grow up to be a “castrating female” who tries to compete with men in the workplace or in other areas of life.

During middle childhood (6-11), the child enters the latency stage focusing his or her attention outside the family and toward friendships. The biological drives are temporarily quieted (latent) and the child can direct attention to a larger world of friends. If the child is able to make friends, he or she will gain a sense of confidence. If not, the child may continue to be a loner or shy away from others, even as an adult.

The final stage of psychosexual development is referred to as the genital stage. From adolescence throughout adulthood a person is preoccupied with sex and reproduction. The adolescent experiences rising hormone levels and the sex drive and hunger drives become very strong. Ideally, the adolescent will rely on the ego to help think logically through these urges without taking actions that might be damaging. An adolescent might learn to redirect their sexual urges into safer activity such as running, for example. Quieting the id with the superego can lead to feeling overly self-conscious and guilty about these urges. Hopefully, it is the ego that is strengthened during this stage and the adolescent uses reason to manage urges.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views.[17]

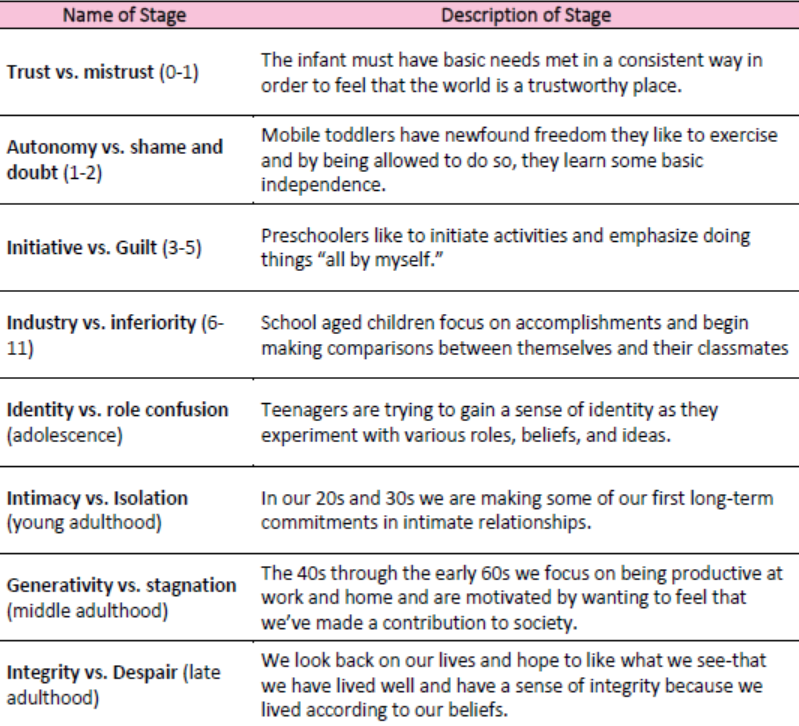

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) and Psychosocial Theory[18]

Erikson suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was a student of Freud’s but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Erikson expanded on his Freud’s by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968).

He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages:

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or “crises” can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. [19]

Learning Theories

While Freud and Erikson looked at what was going on in the mind, learning theories rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior.[20]

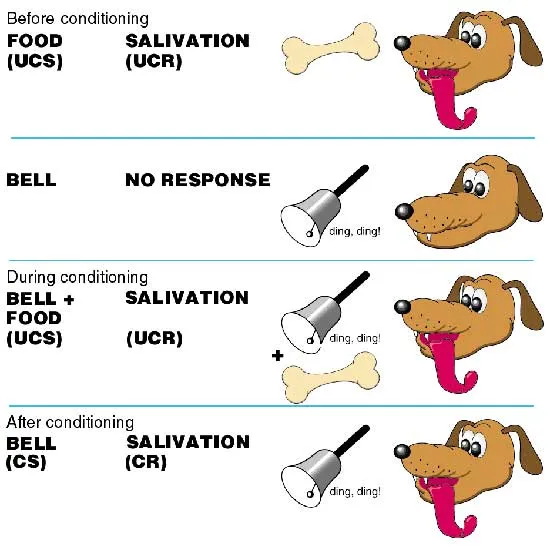

Ivan Pavlov (1870-1937) and Classical Conditioning[21] and Classical Conditioning with Animals

Ivan Pavlov was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to automatically salivate when food hit their palate, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

Pavlov began to experiment with this concept of classical conditioning. He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus. The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Summary of Classical Conditioning Process (Animals)

Pavlovian Conditioning of a dog to salivate upon hearing a bell.

To summarize, classical conditioning (later developed by Watson, 1913) involves learning to associate an unconditioned stimulus that already brings about a particular response (i.e., a reflex) with a new (conditioned) stimulus, so that the new stimulus brings about the same response.

Pavlov developed some rather unfriendly technical terms to describe this process. The unconditioned stimulus (or UCS) is the object or event that originally produces the reflexive /natural response. The response to this is called the unconditioned response (or UCR). The neutral stimulus (NS) is a new stimulus that does not produce a response. Once the neutral stimulus has become associated with the unconditioned stimulus, it becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS). The conditioned response (CR) is the response to the conditioned stimulus.[22]

Now, let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.[23]

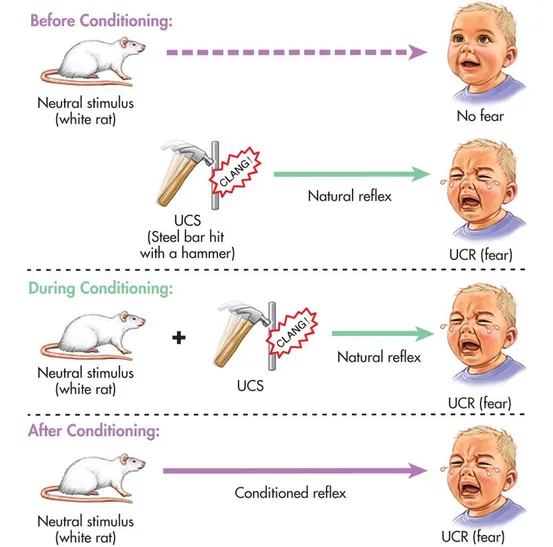

John B. Watson (1878-1958) and Classical Conditioning[24] and Classical Conditioning in Humans

Watson believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public. He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18-month-old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order. [25]

Summary of Classical Conditioning Process (Humans)

Watson’s conditioning of Little Albert to fear a white rat. [26]

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, looks at the way the consequences of a behavior increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. So, let’s look at this a bit more.[27]

B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) and Operant Conditioning[28] and Operant Conditioning in Animals and Humans

Skinner (1904-1990), who brought us the principles of operant conditioning, suggested that reinforcement is a more effective means of encouraging a behavior than is punishment. By focusing on strengthening desirable behavior, we have a greater impact than if we emphasize what is undesirable.

Reinforcement is the process by which a consequence increases the probability of a behavior that it follows. A reinforcer is a specific stimulus or situation that encourages the behavior that it follows. Intrinsic or primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned and satisfy a biological need. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, pleasure, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers. Swimming in a cool lake on a very hot day would be innately reinforcing because the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure. Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers have no inherent value and only have reinforcing qualities when linked with primary reinforcers. They can be traded in for what is ultimately desired. Praise, when linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer. Another example is money, which is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers are things that have a value not immediately understood.

Positive reinforcement occurs when the addition of a stimulus strengthens behavior. For example, positively reinforcing a child with the addition of a cookie for cleaning up will likely make encourage that behavior in the future. Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, occurs when removing a desired stimulus (or preventing access to it) strengthens behavior. For example, an alarm clock makes a very unpleasant, loud sound when it goes off in the morning. As a result, one gets up and turns it off. Therefore, getting up from bed is negatively reinforced through the termination of the aversive sound.

Punishmentis the process by which there decrease in the probability of behavior as a result of the consequence that follows it. Positive punishment occurs when the addition of an unpleasant or painful stimulus weakens behavior. For example, if a child is naughty and receives a spanking, the child will be less likely to misbehave in the future. Negative punishment, on the other hand, weakens a behavior through the removal of a desirable stimulus or preventing access to it. For example, a child who misbehaves and as a result has their favorite toy will be less likely to misbehave in the future. Punishment is often less effective than reinforcement for several reasons. It doesn’t indicate the desired behavior, it may result in suppressing rather than stopping a behavior, (in other words, the person may not do what is being punished when you’re around, but may do it often when you leave), and a focus on punishment can result in not noticing when the person does well.

Examples of Operant Conditioning Using Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Positive and Negative Punishers

| | POSITIVE

(Receive a Stimulus) |

NEGATIVE

(Stimulus Gets Taken Away) |

| REINFORCER

(Probability of Behavior Increases) |

Infant says “Mama” and mother claps her hands, smiles, and says, “very good, yes Mama!” The infant likes seeing the mother perform this way so continues to say “Mama.” | Infant’s diaper is wet or dirty, so infant cries. Someone comes and changes the diaper, thereby reducing the discomfort. The next time the child is uncomfortable, the child will cry. |

| PUNISHER

(Probability of Behavior Decreases) |

Child pulls the dog’s tail and the dog growls at the child. The child becomes frightened and does not pull the dog’s tail again. | Child behaves badly and his toy is taken away. The child learns that particular behavior is unacceptable and doesn’t want to lose the toy again, so the behavior is decreased or eliminated. |

Not all behaviors are learned through association or reinforcement. Many of the things we do are learned by watching others. This is addressed in social learning theory.[29]

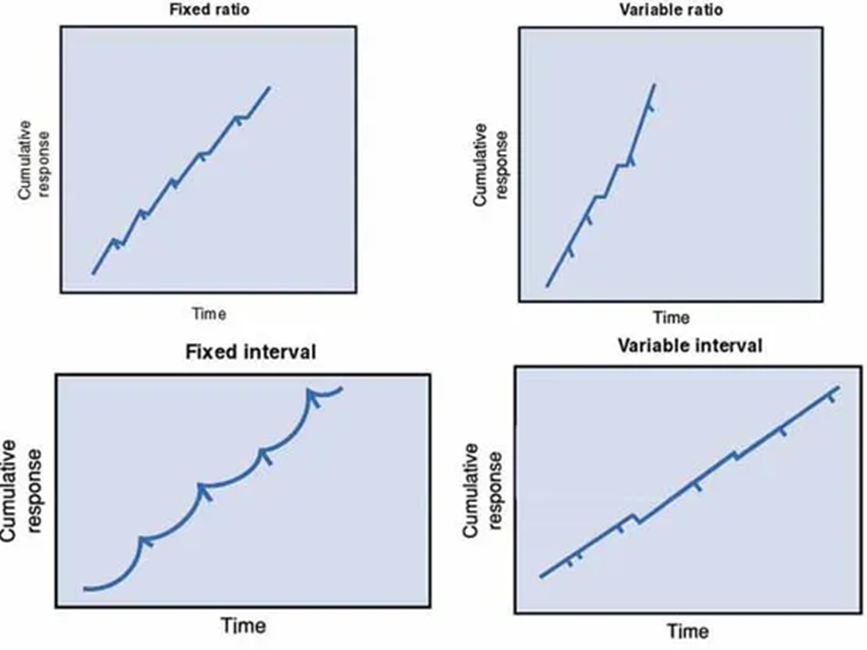

Schedules of Reinforcement

Imagine a rat in a “Skinner box.” In operant conditioning, if no food pellet is delivered immediately after the lever is pressed then after several attempts the rat stops pressing the lever (how long would someone continue to go to work if their employer stopped paying them?). The behavior has been extinguished.

Behaviorists discovered that different patterns or schedules of reinforcement had different effects on the speed of learning and extinction. Ferster and Skinner (1957) devised different ways of delivering reinforcement and found that this had effects on

- The Response Rate – The rate at which the rat pressed the lever (i.e., how hard the rat worked).

- The Extinction Rate – The rate at which lever pressing dies out (i.e., how soon the rat gave up).

Skinner found that the type of reinforcement which produces the slowest rate of extinction (i.e., people will go on repeating the behavior for the longest time without reinforcement) is variable-ratio reinforcement. The type of reinforcement which has the quickest rate of extinction is continuous reinforcement.

Continuous Reinforcement:

An animal/human is positively reinforced every time a specific behavior occurs, e.g., every time a lever is pressed a pellet is delivered, and then food delivery is shut off.

Response rate is SLOW

Extinction rate is FAST

Behavior is reinforced only after the behavior occurs a specified number of times. e.g., one reinforcement is given after every so many correct responses, e.g., after every 5th response. For example, a child receives a star for every five words spelled correctly.

Response rate is FAST

Extinction rate is MEDIUM

One reinforcement is given after a fixed time interval providing at least one correct response has been made. An example is being paid by the hour. Another example would be every 15 minutes (half hour, hour, etc.) a pellet is delivered (providing at least one lever press has been made) then food delivery is shut off.

Response rate is MEDIUM

Extinction rate is MEDIUM

Behavior is reinforced after an unpredictable number of times. For examples gambling or fishing.

Response rate is FAST

Extinction rate is SLOW (very hard to extinguish because of unpredictability)

Variable Interval Reinforcement:

Providing one correct response has been made, reinforcement is given after an unpredictable amount of time has passed, e.g., on average every 5 minutes. An example is a self-employed person being paid at unpredictable times.

Response rate is FAST

Extinction rate is SLOW[30]

Graphic Representation of Schedules of Reinforcement

Each dash indicates the point where reinforcement is given. [31]

Applied Behavior Analysis

Applied behavior analysis (ABA), also known as behavior modification, is based on the application of experimental analysis of behavior findings to create meaningful behavior change in children and adults; thereby improving their well-being. ABA consists of a set of therapies/techniques based on operant conditioning principles (Skinner, 1938, 1953). The main principle comprises changing environmental events that are related to a person’s behavior such as the reinforcement of desired behaviors and the extinction of undesired ones.

Techniques in ABA: Token Economy

One type of applied behavioral analytic technique is the token economy which is frequently used in institutional settings. Tokens, generally in the form of fake money, buttons, poker chips, stickers, etc., can be exchanged for special foods, television time, activities, or other positive reinforcers. For example, teachers use token economies at primary schools by giving young children stickers to reinforce good behavior. Token economies have also been found to be very effective in the management of behavior in people staying in psychiatric hospitals.

Techniques in ABA: Shaping

A further important technique proposed by Skinner (1951) is the concept of shaping. Skinner argues that shaping can be used to produce extremely complex behavior through the differential reinforcement of successive approximations towards that terminal behavior. Upon the successful completion of each behavior in the chain, the contingencies of reinforcement become more stringent. That is, the organism only is reinforced upon the completion of all previous steps plus the next step in the behavior chain. Reinforcement must be discontinued for the previous step(s) in order to propel the organism forward to the terminal behavior. According to Skinner, most animal and human behavior (including language) can be explained through shaping.

Educational Application of Applied Behavior Analysis

A simple way to shape behavior in the classroom is to provide feedback on learner performance, e.g., compliments, approval, encouragement, and affirmation. For example, if a teacher wanted to encourage students to answer questions in class the teacher should praise them for every attempt (regardless of whether their answer is correct). Gradually the teacher will only praise the students when their answer is correct, and over time only exceptional answers will be praised. Unwanted behaviors, such as tardiness and dominating class discussion can be extinguished through the discontinuation of reinforcement by the teacher (i.e., the teacher will stop reinforcing attention-seeking behaviors). Desirable behaviors can be maintained by varying reinforcers. [32]

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) and Social Learning Theory[33] and Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation.

Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by observing others model their behavior and then imitating or copying that behavior. A kindergartner on his or her first day of school might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963).

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us, and we create our environment. [34]

Cognitive Developmental Theories

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) and Theory of Cognitive Development[37]

Jean Piaget is one of the most influential cognitive theorists, and in Chapter 7 we will discuss his work and his legacy in much more detail. Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium. This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour”. All of these are schema. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schema and to modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation. So, the person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our mind. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation. Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schema. Adults tend to look for similarity in their experience and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.”

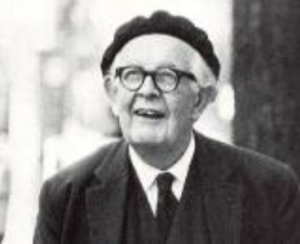

Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this understanding into the following four stages which will be discussed in much more detail in Chapter 7:

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development[38]

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.[39]

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and Sociocultural Theory[40]

Lev Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget (this difference will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 7) in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development.[41]

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators.[42]

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities.[43]

Information Processing

Information Processing is not the work of a single theorist but based on the ideas and research of several cognitive scientists studying how individuals perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information. This approach assumes that humans gradually improve in their processing skills; that is, cognitive development is continuous rather than stage-like. The more complex mental skills of adults are built from the primitive abilities of children. We are born with the ability to notice stimuli, store, and retrieve information. Brain maturation enables advancements in our information processing system. At the same time, interactions with the environment also aid in our development of more effective strategies for processing information.[44]

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) and Ecological Systems Theory[45]

Bronfenbrenner offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.[46] The individual is impacted by several systems including:

- Microsystem includes the individual’s setting and those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents or siblings. The input of those is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence the person’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on him or her.

- Mesosystem includes the larger organizational structures, such as school, the family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule thereby impacting the child, physically, cognitively, and emotionally.

- Exosystem includes the larger contexts of community. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. Mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the exosystem.

- Macrosystem includes the cultural elements, such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the global community.

- Chronosystem is the historical context in which these experiences occur. This relates to the different generational time periods previously discussed, such as the baby boomers and millennials.

In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces, such as the family, schools, religion, culture, and time period. Bronfenbrenner’s model helps us understand all the different environments that impact each one of us simultaneously. Despite its comprehensiveness, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system’s theory is not easy to use. Taking into consideration all the different influences makes it difficult to research and determine the impact of all the different variables (Dixon, 2003). Consequently, psychologists have not fully adopted this approach, although they recognize the importance of the ecology of the individual.[47]

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory[48]

Esther Thelen and Dynamic Systems Theory[49]

The dominant view of motor development for much of the 20th century was that the development of action occurred in a series of relatively fixed motor milestones. The emphasis was on normative development, the concept of motor programs that controlled action, and a sequence of milestones that was largely under genetic or biological control (for review, see Adolph & Berger, 2006). The landscape has shifted dramatically in the last 20 years, thanks in large part to the work of Esther Thelen (as well as other systems thinkers, most notably, Gibson, 1988; see Adolph & Berger, 2006). Today the field views motor development as emergent and exploratory with a new emphasis on individual development in context. Although this revolution in thinking was spurred by dynamic systems concepts, it was also driven forward by a wealth of empirical research.

For instance, Esther Thelen conducted a now-classic set of studies investigating the early disappearance of the stepping reflex. Thelen’s early work on stepping revealed that the coordination patterns that underlie stepping and kicking were strikingly similar. The puzzle was that newborn stepping disappeared within the first three months, whereas kicking continued and increased in frequency. To explain the disappearance of stepping, several researchers had proposed that maturing cortical centers inhibit the primitive stepping reflex or that stepping was phylogenetically programmed to disappear (e.g., Andre-Thomas & Autgaerden, 1966).

To probe the mystery of the disappearing steps, Thelen conducted a longitudinal study that focused on the detailed development of individual infants. Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson (1984) found a clue in the fact that chubby babies and those who gained weight fastest were the first to stop stepping. This led to the hypothesis that it requires more strength for young infants to lift their legs when upright (in a stepping position) than when lying down (in a kicking position). To test this idea, Thelen and colleagues conducted two ingenious studies. In one, they placed small leg weights on two-month-old babies, similar in amount to the weight they would gain in the ensuing month. This significantly reduced stepping. In the other, they submerged older infants whose stepping had begun to wane in water up to chest levels. Robust stepping now reappeared. These data demonstrated that traditional explanations of neural maturation and innate capacities were insufficient to explain the emergence of new patterns and the flexibility of motor behavior.

Since this seminal work, Thelen and her colleagues have intensively examined the development of alternating leg movements (Thelen & Ulrich, 1991), the emergence of crawling (Adolph, Vereijken, & Denny, 1988), the emergence of walking (e.g., Adolph, 1997; Thelen & Ulrich, 1991), and the development of reaching (Corbetta, Thelen, & Johnson, 2000; Thelen, Corbetta & Spencer, 1996; Thelen et al., 1993). In all cases, these researchers have shown that new action patterns emerge in the moment from the self-organization of multiple components. The stepping studies elegantly illustrated this, showing how multiple factors cohere in a moment in time to create or hinder leg movements. And, further, these studies illustrate how changes in the components of the motor system over the longer time scale of development interact with real-time behavior.[50]

Conclusion

Many early theories of human development were created and popularized in the early 1900s. These are referred to as stage theories because they present development as occurring in stages. The assumption is that once one stage is completed, a person moves into the next stage and that stages tend to occur only once. Some examples of stage theories that we will be studying include Freud’s psychosexual stages, Erikson’s psychosocial stages, and Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, to name a few.

These theories are appealing in a way because they provide the ability to predict what will happen next and they allow us to attribute behavior to a person’s being ‘in a stage’. These theories offered the security of understanding human behavior in a time of rapid change during industrialization in the early 1900s. Science seemed to be laying a predictable groundwork we could rely upon. But these early theories also implied that those who did not progress through stages in the predictable way were delayed somehow and this led to the idea that development had to occur in a patterned way.

Today we understand that development does not occur in a straight line. Sometimes we change in many directions depending on our experiences and surroundings. For example, there can be growth and decline in cognitive functioning at any age depending on nutrition, health, activity, and stimulation. And that both nature (heredity) and nurture (the environment) shape our abilities throughout life. Some things about us are continuous such as our temperament or sense of self, perhaps. And we may revisit a stage of life more than once. For instance, Erikson suggests that we struggle with trust as infants and then begin to focus more on independence or autonomy. But if we are in circumstances in which our independence is jeopardized, such as becoming physically dependent, we may struggle with trust again. Keep these thoughts in mind as we explore stage theories in our next lesson.

The study of human development is based on research. The next chapter looks at some of the different types of research methods used to understand development. In other words, how do we know what we know?[51]

Test Yourself: Review of Theories of Childhood Development

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Introduction to Lifespan, Growth and Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Introduction to Lifespan, Growth and Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image by NOBA is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Investment in Early Childhood Development Lays the Foundation for a Prosperous and Sustainable Society by Jack P. Shonkoff, MD, Julius B. Richmond FAMRI Professor of Child Health and Development is found at Importance of early childhood development. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/dossiers-complets/en/importance-of-early-childhood-development.pdf. Updated March 2011. Accessed August 1, 2020. This article is used with permission by Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development. ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Portrait of Locke in 1697 by Godfrey Kneller. Image is public domain. ↵

- Image of Rousseau from Wikimedia Commons and is public domain ↵

- Introduction to Lifespan, Growth and Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Freud is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2019, September 25). Id, ego and superego. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/psyche.html. Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Image from McLeod, S. A. (2019, September 25). Id, ego and superego. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/psyche.html. Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 Text by Maria Pagano ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Erikson is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- History of Psychology by David B. Baker and Heather Sperry is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Image of Pavlov is in the public domain ↵

- Text and image by McLeod, S. A. (2018, October 08). Pavlov's dogs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/pavlov.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Watson is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image by McLeod, S. A. (2018, October 08). Pavlov's dogs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/pavlov.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image of Skinner is public domain ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano and Marie Parnes) ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner - operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner - operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 ↵

- McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner - operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html Licensed under CC BY NC ND 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Image of Albert Bandura is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Exploring Behavior by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0Rasmussen, Eric (2017, Oct 19). Screen Time and Kids: Insights from a New Report. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/parents/thrive/screen-time-and-kids-insights-from-a-new-report ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Image is in the public domain and taken from Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Original document created by Jordy von Hippel and taken from her Developmental Psychology WordPress Blog. No copyright information provided on site. Material updated by Maria Pagano ↵

- Lecture Transcript: Developmental Theories by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Jennifer Paris) ↵

- Image by The Vigotsky Project is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵