11 Emotional Development and Attachment

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 11, you should be equipped to:

- Distinguish between the two categories of emotions and describe the trajectory of emotional development.

- Understand how the nine dimensions combine to for the three types of infant temperament.

- Describe the dynamics of emotional regulation.

- Discuss different types childhood disorders that involve emotional dysregulation.

- Describe development of attachment, the different types of attachment, and reactive attachment disorder

Emotional Development

As we move through our daily lives, we experience a variety of emotions. An emotion is a subjective state of being that we often describe as our feelings. Emotions result from the combination of subjective experience, expression, cognitive appraisal, and physiological responses (Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991). An emotion often begins with a subjective (individual) experience, which is a stimulus. Often the stimulus is external, but it can also be an internal one. For example, if a child thinks about losing a treasured toy, he or she may become sad even though they still have possession of the toy. Emotional expression refers to the way one displays an emotion and includes nonverbal and verbal behaviors (Gross, 1999).[1]

Emotional Development in Infancy

Emotions are often divided into two general categories: Basic emotions (primary emotions), such as interest, happiness, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust, which appear first, and self-conscious emotions (secondary emotions), such as envy, pride, shame, guilt, doubt, and embarrassment. Unlike primary emotions, secondary emotions appear as children start to develop a self-concept, and require social instruction on when to feel such emotions. The situations in which children learn self-conscious emotions vary from culture to culture. Individualistic cultures teach us to feel pride in personal accomplishments, while in more collective cultures children are taught to not call attention to themselves unless they wish to feel embarrassed for doing so (Akimoto & Sanbinmatsu, 1999).[2]

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure, and they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavors or physical discomfort. At around two months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005).

Social Smiling is a form of communication. [3]

Social smiling becomes more stable and organized as infants learn to use their smiles to engage their parents in interactions. Pleasure is expressed as laughter at 3 to 5 months of age, and displeasure becomes more specific as fear, sadness, or anger between ages 6 and 8 months. Anger is often the reaction to being prevented from obtaining a goal, such as a toy being removed (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010). In contrast, sadness is typically the response when infants are deprived of a caregiver (Papousek, 2007). Fear is often associated with the presence of a stranger, known as stranger wariness or stranger anxiety, or the departure of significant others known as separation anxiety. Both appear sometime between 6 and 15 months after object permanence has been acquired. Further, there is some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002).

Social influences and the development of emotions

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. In the developmental literature, this concept has been investigated under the concept of social referencing; that is, the process whereby infants seek out information from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act (Klinnert, Campos, & Sorce, 1983). To date, the strongest demonstration of social referencing comes from work on the visual cliff. In the first study to investigate this concept, Campos and colleagues (Sorce, Emde, Campos, & Klinnert, 1985) placed mothers on the far end of the “cliff” from the infant. Mothers first smiled to the infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them; infants invariably began crawling toward their mothers. When the infants were in the center of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results were clearly different for the different faces; no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear; only 6% did when the mother posed anger, 33% crossed when the mother posed sadness, and approximately 75% of the infants crossed when the mother posed joy or interest.

This mother is encouraging her child to crawl across the visual cliff. The child hesitates to move forward as they see the transparent surface. [4]

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. Researchers posed facial expressions of neutral, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object (Bradshaw, 1986). The results for 10- and 15-month-olds were the same: Anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, with neutral the least. This study was later replicated using joy and disgust expressions, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until one hour after exposure to the expression (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004). At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust. [5]

As infants and toddlers interact with other people, their social and emotional skills continue to develop throughout childhood.[6]

Empathy

A person can acquire emotions, such as anger and happiness, from people around him or her. This process is called emotional contagion, whereby emotional expression of a person leads another person to experience a similar emotional state (Bruder et al., 2012; Peters and Kashima, 2015). A component of emotional contagion, emotional mimicry, is defined as the imitation of the facial, verbal, or postural expressions of others (Hatfield et al., 1993; Hess and Fischer, 2013). For example, newborn babies will cry when they hear others crying.[7]

During childhood, the development of empathy is a crucial part of emotional and social development in childhood. The ability to identify with the feelings of another person helps in the development of prosocial (socially positive) and altruistic (helpful, beneficent, or unselfish) behavior. Altruistic behavior occurs when a person does something in order to benefit another person without expecting anything in return. Empathy helps a child develop positive peer relationships; it is affected by a child’s temperament, as well as by parenting style. Children raised in loving homes with affectionate parents are more likely to develop a sense of empathy and altruism, whereas those raised in harsh or neglectful homes tend to be more aggressive and less kind to others.[8]

Empathy begins to increase in adolescence and is an important component of social problem-solving and conflict avoidance. According to one longitudinal study, levels of cognitive empathy begin rising in girls around 13 years old, and around 15 years old in boys (Van der Graaff et al., 2013). Teens who reported having supportive fathers with whom they could discuss their worries were found to be better able to take the perspective of others (Miklikowska, Duriez, & Soenens, 2011).[9]

Temperament

Perhaps you have spent time with a number of infants. How were they alike? How did they differ? How do you compare with your siblings or other children you have known well? You may have noticed that some seemed to be in a better mood than others and that some were more sensitive to noise or more easily distracted than others. These differences may be attributed to temperament. Temperament is the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth.

In a 1956 landmark study, Chess and Thomas (1996) evaluated 141 children’s temperaments based on parental interviews. Referred to as the New York Longitudinal Study, infants were assessed on 9 dimensions of temperament including:

- Activity level, rhythmicity (regularity of biological functions),

- approach/withdrawal (how children deal with new things),

- adaptability to situations

- intensity of reactions

- threshold of responsiveness (how intense a stimulus has to be for the child to react)

- quality of mood

- distractibility

- attention span

- persistence.

Based on the infants’ behavioral profiles, they were categorized into three general types of temperament:

- Easy Child (40%) who is able to quickly adapt to a routine and new situations, remains calm, is easy to soothe, and usually is in a positive mood.

- Difficult Child (10%) who reacts negatively to new situations, has trouble adapting to routine, is usually negative in mood, and cries frequently.

- Slow-to-Warm-Up Child (15%) has a low activity level, adjusts slowly to new situations, and is often negative in mood.

As can be seen, the percentages do not equal 100% as some children were not able to be placed neatly into one of the categories. Think about how you might approach each type of child in order to improve your interactions with them. An easy child will not need much extra attention, while a slow-to-warm-up child may need to be given advance warning if new people or situations are going to be introduced. A difficult child may need to be given extra time to burn off their energy. A caregiver’s ability to work well and accurately read the child will enjoy a goodness-of-fit, meaning their styles match and communication and interaction can flow. Parents who recognize each child’s temperament and accept it will nurture more effective interactions with the child and encourage more adaptive functioning. For example, an adventurous child whose parents regularly take her outside on hikes would provide a good “fit” for her temperament.

Parenting is bidirectional: Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as temperament, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, & Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influence how parents behave with their children.

Temperament does not change dramatically as we grow up, but we may learn how to work around and manage our temperamental qualities. Temperament may be one of the things about us that stays the same throughout development. In contrast, personality is the result of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience.

Personality also develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics emerge and change over time. A newborn is not capable of much self-control, but as brain-based capacities for self-control advance, temperamental changes in self-regulation become more apparent. For example, a newborn who cries frequently does not necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and an increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to cry.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, and many other qualities are encompassed in personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics. Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that parents gazed upon becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance.[10]

Emotional Regulation and Self Control

A final emotional change is in self-regulation. Emotional self-regulation refers to strategies we use to control our emotional states so that we can attain goals (Thompson & Goodvin, 2007). This requires effortful control of emotions and initially requires assistance from caregivers (Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, 2006). Young infants have very limited capacity to adjust their emotional states and depend on their caregivers to help soothe themselves. Caregivers can offer distractions to redirect the infant’s attention and provide comfort to reduce emotional distress. As areas of the infant’s prefrontal cortex continue to develop, infants can tolerate more stimulation. By 4 to 6 months, babies can begin to shift their attention away from upsetting stimuli (Rothbart et al, 2006). Older infants and toddlers can more effectively communicate their need for help and can crawl or walk toward or away from various situations (Cole, Armstrong, & Pemberton, 2010). This aids in their ability to self-regulate. Temperament also plays a role in children’s ability to control their emotional states, and individual differences have been noted in the emotional self-regulation of infants and toddlers (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).[11]

It is in early childhood that we see the start of self-control, a process that takes many years to fully develop. According to Lecci & Magnavita (2013), “Self-regulation is the process of identifying a goal or set of goals and, in pursuing these goals, using both internal (e.g., thoughts and affect) and external (e.g., responses of anything or anyone in the environment) feedback to maximize goal attainment” (p. 6.3). Self-regulation is also known as willpower. When we talk about willpower, we tend to think of it as the ability to delay gratification. For example, Bettina’s teenage daughter made strawberry cupcakes, and they looked delicious. However, Bettina forfeited the pleasure of eating one, because she is training for a 5K race and wants to be fit and do well in the race. Would you be able to resist getting a small reward now in order to get a larger reward later? This is the question Walter Mischel investigated in his now-classic “marshmallow test.”

Can this child delay gratification for a larger reward? [12]

Mischel designed a study to assess self-regulation in young children. In the marshmallow study, Mischel and his colleagues placed a preschool child in a room with one marshmallow on the table. The child was told that he could either eat the marshmallow now or wait until the researcher returned to the room and then he could have two marshmallows (Mischel, Ebbesen & Raskoff, 1972). This was repeated with hundreds of preschoolers. What Mischel and his team found was that young children differ in their degree of self-control. Mischel and his colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and what do you think they discovered? The children who had more self-control in preschool (the ones who waited for the bigger reward) were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores, had positive peer relationships, and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable marriages (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Mischel et al., 2010). On the other hand, those children who had poor self-control in preschool (the ones who grabbed the one marshmallow) were not as successful in high school, and they were found to have academic and behavioral problems.[13]

Emotional intelligence

The concept of emotional intelligence was introduced in the 60s and rose in popularity with the release of Daniel Goleman’s 1995 book Emotional Intelligence – Why it can matter more than IQ. [14]

Emotional Intelligence (EI) can be generally defined as how we perceive, communicate, regulate, and understand our own emotions, as well as the emotions of others. According to Lane (2000a), the most pivotal aspect of EI is probably related to the awareness of emotional experiences in oneself and others. Investigations of EI in children have suggested that a higher EI level appears to be an important predictive factor of health-related outcomes, such as improved well-being and social interactions during development (Andrei et al., 2014), as well as fewer somatic complaints (e.g., Jellesma et al., 2011). EI appears to have a positive impact on children’s adaptive capacities (Mavroveli et al., 2008; Davis and Humphrey, 2012). A number of studies on EI through childhood have been conducted within educational settings; showing that EI can be important for positive adaptation within the classroom, with particular implications for social-emotional competencies and for consequent adaptive behaviors with peers (Frederickson et al., 2012). For instance, Petrides et al. (2004) showed that pupils with high EI scores were less likely to be expelled from their schools and had a lower frequency of unauthorized absences. Additional studies revealed that high EI scores were positively associated with multiple peer ratings for prosocial behavior (Mavroveli et al., 2009). Moreover, data from self-report surveys revealed that a high EI is negatively related to bullying (Mavroveli and Sánchez-Ruiz, 2011), and victimization attitude (Kokkinos and Kipritsi, 2012), and behavioral problems in general (Poulou, 2014). Although the literature still lacks clear and direct results regarding this relationship (Mavroveli et al., 2009; Hansenne and Legrand, 2012), it seems that EI may moderate the relationship between intelligence and scholastic performance (Agnoli et al., 2012). Overall, high EI (especially in the ability to regulate emotions) is associated with several positive outcomes for children. [15]

Emotional Disorders

Many children have fears and worries and may feel sad and hopeless from time to time. Strong fears may appear at different times during development. For example, toddlers are often very distressed about being away from their parents, even if they are safe and cared for. Although some fears and worries are typical in children, persistent or extreme forms of fear and sadness could be due to anxiety or depression. [16]

Mental health disorders are diagnosed by a qualified professional using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). This is a manual that is used as a standard across the profession for diagnosing and treating mental disorders.[17]

Persistent or extreme forms of fear and sadness could be due to anxiety or depression. [18]

Depression

Occasionally being sad or feeling hopeless is a part of every child’s life. However, some children feel sad or uninterested in things that they used to enjoy, or feel helpless or hopeless in situations where they could do something to address the situations. When children feel persistent sadness and hopelessness, they may be diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).[19]

We now know that youth who have depression may show signs that are slightly different from the typical adult symptoms of depression. Children who are depressed may complain of feeling sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent or caregiver, feel unloved, hopeless about the future, or worry excessively that a parent may die. Older children and teens may sulk, get into trouble at school, be negative or grouchy, are irritable, indecisive, have trouble concentrating, or feel misunderstood. Because normal behaviors vary from one childhood stage to another, it can be difficult to tell whether a child who shows changes in behavior is just going through a temporary “phase” or is suffering from depression. [20]

Younger children with depression may pretend to be sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent, or worry that a parent may die.[21] Although MDD can be diagnosed in younger children, it is not very common[22]

Older children and teens with depression may get into trouble at school, sulk, and be irritable. Teens with depression may have symptoms of other disorders, such as anxiety, eating disorders, or substance abuse.[23] However, it is the first cause of disability among adolescents aged 10 to 19 years (WHO 2014). Suicide is the third cause of death in this age group, and adolescent depression is a major risk factor for suicide. Depressed adolescents experienced significantly more stressors during the year before onset when compared with a comparable 12-month period in normal controls. [24]

Anxiety

Many children have fears and worries and may feel sad and hopeless from time to time. Strong fears may appear at different times during development. For example, toddlers are often very distressed about being away from their parents, even if they are safe and cared for. Although fears and worries are typical in children, persistent or extreme forms of fear and sadness could be due to anxiety or depression. Because the symptoms primarily involve thoughts and feelings, they are called internalizing disorders.

Internalizing disorders involve thoughts and feelings. [25]

When a child does not outgrow the fears and worries that are typical in young children, or when there are so many fears and worries that they interfere with school, home, or play activities, the child may be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Examples of different types of anxiety disorders include:

- Being very afraid when away from parents (separation anxiety)

- Having extreme fear about a specific thing or situation, such as dogs, insects, or going to the doctor (phobia)

- Being very afraid of school and other places where there are people (social anxiety)

- Being very worried about the future and about bad things happening (general anxiety)

- Having repeated episodes of sudden, unexpected, intense fear that come with symptoms like heart pounding, having trouble breathing, or feeling dizzy, shaky, or sweaty (panic disorder)

Anxiety may present as fear or worry, but can also make children irritable and angry. Anxiety symptoms can also include trouble sleeping, as well as physical symptoms like fatigue, headaches, or stomachaches. Some anxious children keep their worries to themselves and, thus, the symptoms can be missed.[26]

Treatment for Anxiety and Depression

The first step to treatment is to have the child evaluated by a healthcare provider or a mental health specialist. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends that healthcare providers routinely screen children for behavioral and mental health concerns. Some of the signs and symptoms of anxiety or depression in children could be caused by other conditions, such as trauma. It is important to get a careful evaluation to get the best diagnosis and treatment. A mental health professional can develop a therapy plan that works best for the child and family, and for very young children, involving parents in treatment is key.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered a well-established treatment for adult, adolescent, and pre-adolescent depression and anxiety, and is based on the core principles that psychological problems like depression and anxiety stem from faulty ways of thinking and learned patterns of behavior that are unproductive.

CBT was developed to change an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that stem from dysfunctional cognitive patterns (ie, “I made a mistake and therefore I am a failure”) as well as maladaptive behavioral patterns (ie, withdrawal, social isolation). CBT is a “here and now,” approach that is goal oriented and designed to reduce a client’s presenting symptoms. Although CBT is heterogeneous and comprised of several different treatment components, common components include cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, social skills training, and problem solving. [27]

Family-based interpersonal psychotherapy (FB-IPT) Family-based interpersonal psychotherapy is conceptually rooted in an interpersonal model of depression and in developmental research on the antecedents of depression in youths. FB-IPT focuses on improving two domains of interpersonal impairment in preadolescents with depression, parent-child conflict and difficulty in peer relationships, to decrease preadolescents’ depressive symptoms. FB-IPT focuses on improving communication and problem-solving skills in the parent-child relationship, the primary context for children’s social and emotional development, as a means to improve the quality of the parent-child relationship and to promote effective interpersonal behavior with peers. Adapted from IPT for adolescents with depression (IPT-A) , FB-IPT includes several developmental modifications for 8–12-year-olds: increased parental involvement and structured dyadic sessions with preadolescents and parents (to teach and role-play communication and problem-solving skills), an expanded limited sick role (to direct parental expectations for the performance of preadolescents with depression across contexts), parenting strategies for decreasing conflict, increased focus on the effect of anxiety on peer relationships (to increase frequency of initiating interactions with peers), and use of effective communication and interpersonal problem-solving skills with peers.[28]

Consultation with a health provider can help determine if medication should be part of the treatment. [29] It is important to note that although antidepressants can be effective for many people, they may present serious risks to some, especially children, teens, and young adults. Antidepressants may cause some people, to have suicidal thoughts or make suicide attempts. [30]

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

In 2013, the 5th revision to the DSM (DSM-5) added a chapter on disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. It brings together several disorders that were previously included in other chapters (such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, pyromania, and kleptomania) into one single category. These disorders are marked by behavioral and emotional disturbances specifically related to self-control.

Conduct Disorder

According to the DSM-5, conduct disorder (CD) is defined as,” A repetitive and persistent pattern of behavior in which the basic rights of others or major age-appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of three (or more) of the following 15 criteria in the past 12 months from any of the categories below, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months:

Aggression to People and Animals:

Destruction of Property:

Serious Violations of Rules:

| Conduct Disorder Onset Type |

| Childhood-Onset Type: Individuals show at least 1 symptom characteristic of conduct disorder prior to age 10. |

| Adolescent-Onset Type: Individuals show no symptoms characteristic of conduct disorder prior to the age of 10. |

| Unspecified Onset: Criteria for diagnosis of conduct disorder are met, but there is not enough information available to determine whether the onset of the first symptoms was before or after the age of 10. |

Conduct disorder can be specified as, (1) mild, where few if any conduct problems in excess of those required to make the diagnosis are present, and conduct problems cause relatively minor harm to others(i.e. lying), (2) moderate, where the number of conduct problems and the effect on others is intermediate between those specified in “mild” and those in “severe” (i.e. stealing without confronting a victim), or severe, where the child exhibits behaviors in excess of those required to meet the diagnosis, or conduct problems causing considerable harm to others (i.e. physical cruelty to a human or animal).

Treatment for Individuals with Conduct Disorder.

The most effective treatment for an individual with conduct disorder is one that seeks to integrate individual, school, and family settings. Additionally, treatment should also seek to address familial conflicts such as marital discord or maternal depression. In this manner, a treatment would serve to address many of the possible triggers of conduct problems. Several treatments currently exist, the most effective of which is multi-systemic treatment (MST), an intensive, integrative treatment that emphasizes how an individual’s conduct problems fit within a broader context.[34] MST is often used with juveniles who have committed serious criminal offenses and who are possibly abusing substances. It is also a therapy strategy to teach their families how to foster their success in recovery.

The goals of MST are to lower rates of criminal behavior in juvenile offenders. There are several things MST therapy must include: integration of empirically based treatment to acknowledge a large variety of risk factors that may be influencing the behavior (for example The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), which quickly assesses the severity of substance abuse and identifies the appropriate level of treatment) ; rewards for positive changes in behavior and environment to ultimately empower caregivers; and many thorough quality assurance mechanisms that focus on completing objectives set in treatment. In this intensive intervention, at least one team of two to four therapists and a therapist supervisor provides around 60 to 100 hours of direct services, typically over the course of three to six months. MST is based in part on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, and therapists address individual, family, peer, school, and neighborhood risk factors that lead to antisocial behavior. MST also is informed by the theory that the family is the key to affecting change. MST works to improve parenting practices and family relationships and functioning in order to reduce antisocial behavior.

Therapists follow a process called the MST Analytic Process (or “Do Loop”) in which they work with the client and family to identify and address “drivers,” or factors which could contribute to antisocial behaviors. “Drivers” could include many factors that affect the client, such as caregiver unemployment, substance use, or lack of supervision, and client association with deviant peers and lack of involvement in school. Treatment depends on the “drivers” and often may involve establishing a behavior plan at home, increasing caregiver monitoring of behavior, addressing disputes with parents and teachers, reducing the client’s interactions with deviant peers, and helping the client establish prosocial behaviors and peer groups. Overall, treatment is individualized depending on the social systems surrounding the youth. Although treatment is highly variable, it always includes nine core principles (See table below)[35].

MST Nine Core Principles[36]

| Principle 1: Finding the fit |

| The primary purpose of assessment is to understand the “fit” between the identified problems and their broader systemic context. |

| Principle 2: Focusing on positives and strengths |

| Therapeutic contacts should emphasize the positive and should use systemic strengths as levers for change. |

| Principle 3: Increasing responsibility |

| Interventions should be designed to promote responsible behavior and decrease irresponsible behavior among family members. |

| Principle 4: Present focused, action oriented and well-defined |

| Interventions should be present-focused and action-oriented, targeting specific and well-defined problems. |

| Principle 5: Targeting sequences |

| Interventions should target sequences of behavior within or between multiple systems that maintain the identified problems. |

| Principle 6: Developmentally appropriate |

| Interventions should be developmentally appropriate and fit the developmental needs of the youth. |

| Principle 7: Continuous effort |

| Interventions should be designed to require daily or weekly effort by family members. |

| Principle 8: Evaluation and accountability |

| Intervention efficacy is evaluated continuously from multiple perspectives with providers assuming accountability for overcoming barriers to successful outcomes. |

| Principle 9: Generalization |

| Interventions should be designed to promote treatment generalization and long-term maintenance of therapeutic change by empowering caregivers to address family members’ needs across multiple systemic contexts. |

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is listed in the DSM-5 under Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders and defined as “a pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness”. This can include frequent temper tantrums, excessive arguing with adults, refusing to follow rules, purposefully upsetting others, getting easily irked, having an angry attitude, and vindictive acts that are usually targeted toward peers, parents, teachers, and other authority figures. Unlike conduct disorder (CD), those with ODD do not show patterns of aggression towards people or animals, destruction of property, theft, or deceit.

ODD gradually develops and becomes apparent in preschool years, often before the age of eight years old. Children with ODD usually begin showing symptoms around age 6 to 8, although the disorder can emerge in younger children too. Symptoms can last throughout teenage years however, it is very unlikely to emerge following early adolescence.

There is a difference in prevalence between boys and girls, with a ratio of 1.4 to 1 before adolescence, with the prevalence for girls increasing after puberty. Researchers have found that the general prevalence of ODD throughout cultures remains constant (approximately 3.6% of the population up to age 18), but the difference in ODD prevalence between sexes is only significant in Western cultures. It is possible that there is a decreased prevalence of ODD in boys or an increased prevalence of ODD in girls in non-Western cultures, but it is also possible that the disorder is either over- or under-diagnosed in boys or girls in Western cultures.

Symptoms of ODD

In order for a child or adolescent to be diagnosed with ODD, that individual must exhibit four out of the eight signs and symptoms that include;

- Often loses temper

- Is often touchy or easily annoyed

- Is often angry and resentful

- Often argues with authority figures or, for children and adolescents, with adults

- Often actively defies or refuses to comply with requests from authority figures or with rules

- Often deliberately annoys others

- Often blames others for their mistakes or misbehavior

- Has been spiteful or vindictive at least twice within the past six months

While these behaviors can be typical among siblings, the behaviors must be observed with individuals other than siblings for an ODD diagnosis. Furthermore, the behaviors must be perpetuated for longer than six months and must be considered beyond a normal child’s age, gender and culture to fit the diagnosis. For children under five years of age, they must occur on most days over a period of six months. For children over five years of age, they must occur at least once a week for at least six months. If symptoms are confined to only one setting, most commonly home, it is considered mild in severity. If it is observed in two settings, it is characterized as moderate, and if the symptoms are observed in three or more settings, it is considered severe.

For a child or adolescent to qualify for a diagnosis of ODD, behaviors must cause considerable distress for the family or interfere significantly with academic or social functioning. Interference might take the form of preventing the child or adolescent from learning at school or making friends or placing him or her in harmful situations. These behaviors must also persist for at least six months. Effects of ODD can be greatly amplified by other disorders in comorbidity such as ADHD. Other common comorbid disorders include depression and substance use disorders. Adults who were diagnosed with ODD as children tend to have a higher chance of being diagnosed with other mental illness in their lifetime, as well as being at higher risk of developing social and emotional problems.[37]

Many pregnancies and birth problems are related to the development of conduct problems; however, strong evidence for causation is lacking. Malnutrition, specifically protein deficiency, lead poisoning, and a mother’s use of nicotine, marijuana, alcohol, or other substances during pregnancy may increase the risk of developing ODD. Deficits and injuries to certain areas of the brain can also lead to serious behavioral problems in children. Brain imaging studies have suggested that children with ODD may have subtle differences in the part of the brain responsible for reasoning, judgment, and impulse control.

Approaches to the treatment of ODD include parent management training, individual psychotherapy, family therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and social skills training. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, treatments for ODD are tailored specifically to the individual child, and different treatment techniques are applied for pre-schoolers and adolescents. Several preventative programs have had a positive effect on those at high risk for ODD. Both home visitation and programs such as Head Start have shown some effectiveness in preschool children. Social skills training, parent management training, and anger management programs have been used as prevention programs for school-age children at risk for ODD. For adolescents at risk for ODD, cognitive interventions, vocational training, and academic tutoring have shown preventative effectiveness.[38]

Prolonged defiance and argumentative behaviors are some signs of ODD. [39]

Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Intermittent explosive disorder (IED) is a behavioral disorder characterized by explosive outbursts of anger and/or violence, often to the point of rage, that are disproportionate to the situation at hand (e.g., impulsive shouting, screaming or excessive reprimanding triggered by relatively inconsequential events), is not premeditated, and is defined by a disproportionate reaction to any provocation, real or perceived. Some individuals have reported affective changes prior to an outburst, such as tension, mood changes, and energy changes

The disorder is currently categorized in the DSM-5 under the “Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders” category. The disorder itself is not easily characterized and often exhibits comorbidity with other mood disorders, particularly bipolar disorder. Individuals diagnosed with IED report their outbursts as being brief (lasting less than an hour), with a variety of bodily symptoms (sweating, stuttering, chest tightness, twitching, palpitations) reported by a third of one sample. Aggressive acts are frequently reported to be accompanied by a sensation of relief and in some cases pleasure, but often followed by later remorse.

The current criteria for a diagnosis of IED include the following symptoms:

- Recurrent outbursts that demonstrate an inability to control impulses, including either of the following:

- Verbal aggression (tantrums, verbal arguments, or fights) or physical aggression that occurs twice in a week-long period for at least three months and does not lead to the destruction of property or physical injury

- Three outbursts that involve injury or destruction within a year-long period

- Aggressive behavior grossly disproportionate to the magnitude of the psychosocial stressors

- The outbursts are not premeditated and serve no premeditated purpose

- The outbursts cause distress or impairment of functioning or lead to financial or legal consequences

- The individual must be at least six years old

- The recurrent outbursts cannot be explained by another mental disorder and are not the result of another medical disorder or substance use

Diagnosing IEDs is done by using a psychiatric interview which requires that, (1) several episodes of impulsive behavior that result in serious damage to either persons or property, wherein (2) the degree of the aggressiveness is grossly disproportionate to the circumstances or provocation, and (3) the episodic violence cannot be better accounted for by another mental or physical medical condition. In addition, the diagnosis can only be given to individuals 6 years of age or older, and the recurrent outbursts cannot be explained by another mental disorder and are not the result of another medical disorder or substance use.

Impulsive behavior, and especially impulsive violence predisposition, have been correlated to differences in levels of serotonin in the brain. IED may also be associated with lesions in the prefrontal cortex, with damage to these areas, including the amygdala, increasing the incidence of impulsive and aggressive behavior and the inability to predict the outcomes of an individual’s own actions. Lesions in these areas are also associated with improper blood sugar control, leading to decreased brain function in these areas, which are associated with planning and decision-making.

Although there is no cure, treatment is attempted through cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotropic medication regimens, though the pharmaceutical options have shown limited success. Therapy aids in helping the patient recognize the impulses in hopes of achieving a level of awareness and control of the outbursts, along with treating the emotional stress that accompanies these episodes. Cognitive Relaxation and Coping Skills Therapy (CRCST) has shown preliminary success in both group and individual settings compared to control groups.[40]

Theories of Attachment

Attachment is a deep and enduring emotional bond that connects one person to another across time and space (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1969). Psychologists have proposed two main theories that are believed to be important in forming attachments. The learning/behaviorist theory of attachment (e.g., Dollard & Miller, 1950) suggests that attachment is a set of learned behaviors. The basis for the learning of attachments is the provision of food. An infant will initially form an attachment to whoever feeds it. They learn to associate the feeder (usually the mother) with the comfort of being fed and through the process of classical conditioning, come to find contact with the mother comforting. They also find that certain behaviors (e.g., crying, smiling) bring desirable responses from others (e.g., attention, comfort), and through the process of operant conditioning learn to repeat these behaviors to get the things they want.

The evolutionary theory of attachment (e.g., Bowlby, Harlow, Lorenz) suggests that children come into the world biologically pre-programmed to form attachments with others because this will help them to survive. The infant produces innate ‘social releaser’ behaviors such as crying and smiling that stimulate innate caregiving responses from adults. The determinant of attachment is not food, but care and responsiveness.

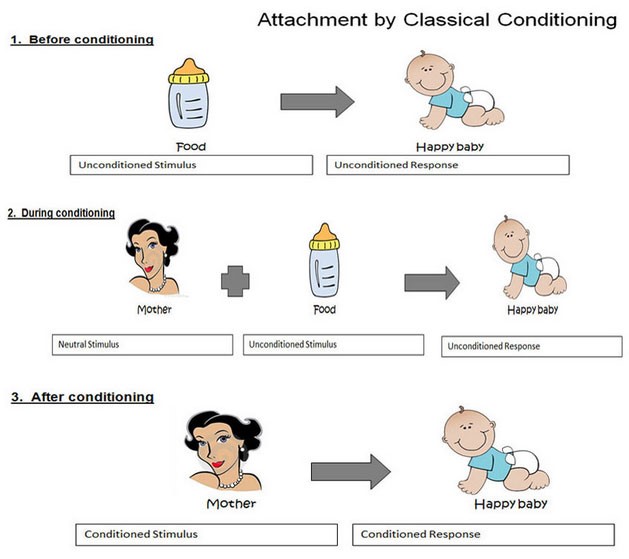

Classical and Operant Conditioning of Attachment

From earlier readings you learned that according to behaviorists like Watson and Skinner proposed that behaviors such as attachment are not innate, but learned. In the case of Watson, learning occurred as a result of associations made between different stimuli (classical conditioning), and in the case of Skinner behaviors can be altered by patterns of reinforcement and punishment (operant conditioning). In the case of classical conditioning, Watson might explain attachment as a result of the child associating the mother with food, much in the way Pavlov showed that dogs salivated to the sound of a bell. At the outset, the mother is a neutral stimulus (NS), however because the mother becomes associated with food (unconditioned stimulus), the mother will quickly become a conditioned stimulus. As a result of this association, the infant learns to associated the feeder (typically the mother) with the comfort of being fed and through the process of classical conditioning, come to find contact with the mother comforting as illustrated below.

Certain infant behaviors, (e.g. crying, smiling) bring desirable responses from those around them (e.g. attention, comfort), and through the process of operant conditioning the infant learns to repeat these behaviors in order to get the things that they want. For example if the child cries due to the discomfort of a wet or soiled diaper, and the caregiver responds by changing the dirty diaper, the child has now been negatively reinforced (something uncomfortable has been removed, which increases the possibility of the behavior continuing) to cry at the feeling of discomfort. Moreover, when the child cries, this is unpleasant for the caregiver, who does not want to see their child uncomfortable, and so changing the diaper also serves as a negative reinforcer for the caregiver because changing the soiled diaper eliminates the crying. [41]

Dollard & Miller (1950) used the term secondary drive hypothesis to describe the processes of learning an attachment through operant and classical conditioning. Secondary drive theory explains how primary drives which are essential for survival, such as eating when hungry, become associated with secondary drives such as emotional closeness. They extended the theory to explain that attachment is a two way process that the caregiver must also learn, and this occurs through negative reinforcement when the caregiver feels pleasure because the infant is no longer distressed.

Learning theory provides a very plausible and scientifically reliable explanation for attachment formation. It seems highly likely that simple association between the provision of needs essential for survival and the person providing those needs can lead to strong attachments. However the theory is extremely reductionist and there is evidence that infants can form attachments with a person who is not the primary care-giver.

Schaffer & Emerson (1964) studied the attachments formed by 60 infants from birth. They found that a significant number of infants formed attachments with a person other than the one doing the feeding, nappy changing, etc. and that the primary attachment was often with the father and not the mother. They found that it was the quality of interaction with the infant that was most important – stronger attachments were formed with the person who was most sensitive and responsive to the infant’s needs.[42]

Evolutionary Theories of Psychology

In the 1930s John Bowlby worked as a psychiatrist in a Child Guidance Clinic in London, where he treated many emotionally disturbed children. This experience led Bowlby to consider the importance of the child’s relationship with their mother in terms of their social, emotional, and cognitive development. Specifically, it shaped his belief about the link between early infant separations from the mother and later maladjustment and led Bowlby to formulate his attachment theory.

John Bowlby, working alongside James Robertson (1952) observed that children experienced intense distress when separated from their mothers. Even when such children were fed by other caregivers, this did not diminish the child’s anxiety. Bowlby suggested that a child would initially form only one primary attachment (monotropy) and that the attachment figure acted as a secure base for exploring the world. The attachment relationship acts as a prototype for all future social relationships so disrupting it can have severe consequences. These findings contradicted the dominant behavioral theory of attachment (Dollard and Miller, 1950) which was shown to underestimate the child’s bond with their mother.

Bowlby defined attachment as a ‘lasting psychological connectedness between human beings (1969, p. 194). He proposed that attachment can be understood within an evolutionary context in that the caregiver provides safety and security for the infant. Attachment is adaptive as it enhances the infant’s chance of survival. According to Bowlby infants have a universal need to seek close proximity with their caregiver when under stress or threatened (Prior & Glaser, 2006). Bowlby suggested that attachment is an innate (unlearned, instinctual) process, which is evolutionarily beneficial – those infants that did become attached would be more likely to be cared for by an adult, and therefore more likely to survive and pass on this behavior genetically.

Bowlby’s observations led him to conclude that there is a critical period for developing an attachment (about 0 -5 years), and if an attachment has not developed during this period, then the child will suffer from irreversible developmental consequences, such as reduced intelligence and increased aggression. According to Bowlby, infant development of attachment developed across the following 4 stages found in the table below.

Bowlby’s 4 Stages of Infant Attachment

| STAGE | AGE | INFANT CHARACTERISTICS |

| Pre-Attachment | Newborn to 6 Weeks |

No attachment to any specific individual. The infant does not show any preference for a particular individual and will not fuss when picked up by a stranger.

|

| Attachment in the Making | 6 Weeks to 6-8 Months |

The infant begins to show preferences for caregivers, predominantly for the primary caregiver over strangers. The primary caregiver can typically soothe the baby more easily than others.

|

| Clear-Cut Attachment | 6-8 Months to 18-24 Months |

A clear attachment has been formed between the primary caregiver and infant, and when separated the infant will become upset (separation anxiety)

|

| Formation of Reciprocal Relationships | 24 Months and Older | As the child begins to develop mental representations of others this leads to the formation of multiple attachments with other who often interact with the infant |

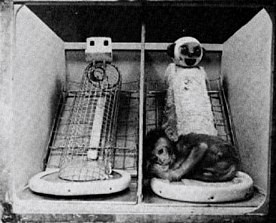

Harry Harlow (1958) wanted to study the mechanisms by which newborn rhesus monkeys bond with their mothers. These infants were highly dependent on their mothers for nutrition, protection, comfort, and socialization. What, exactly, though, was the basis of the bond?

The behavioral theory of attachment would suggest that an infant would form an attachment with a caregiver that provides food. In contrast, Harlow’s explanation was that attachment develops as a result of the mother providing “tactile comfort,” suggesting that infants have an innate (biological) need to touch and cling to something for emotional comfort. Harry Harlow did a number of studies on attachment in rhesus monkeys during the 1950s and 1960s. His experiments took several forms:

- Infant monkeys reared in isolation– He took babies and isolated them from birth. They had no contact with each other or anybody else. He kept some this way for three months, some for six, some for nine, and some for the first year of their lives. He then put them back with other monkeys to see what effect their failure to form attachment had on behavior. As a result, the monkeys engaged in bizarre behavior such as clutching their own bodies and rocking compulsively. They were then placed back in the company of other monkeys. To start with the babies were scared of the other monkeys, and then became very aggressive towards them. They were also unable to communicate or socialize with other monkeys. The other monkeys bullied them. They indulged in self-mutilation, tearing hair out, scratching, and biting their own arms and legs. Harlow concluded that privation (i.e., never forming an attachment bond) is permanently damaging (to monkeys). The extent of the abnormal behavior reflected the length of the isolation. Those kept in isolation for three months were the least affected, but those in isolation for a year never recovered the effects of privation.

Wire and cloth surrogates [43]

- Infant monkeys reared with surrogate mothers– 8 monkeys were separated from their mothers immediately after birth and placed in cages with access to two surrogate mothers, one made of wire and one covered in soft terry toweling cloth. Four of the monkeys could get milk from the wire mother and four from the cloth mother. The animals were studied for 165 days. Both groups of monkeys spent more time with the cloth mother (even if she had no milk). The infant would only go to the wire mother when hungry. Once fed it would return to the cloth mother for most of the day. If a frightening object was placed in the cage the infant took refuge with the cloth mother (its safe base). This surrogate was more effective in decreasing the youngster’s fear. The infant would explore more when the cloth mother was present. This supports the evolutionary theory of attachment, in that it is the sensitive response and security of the caregiver that is important (as opposed to the provision of food).

The behavioral differences that Harlow observed between the monkeys who had grown up with surrogate mothers and those with normal mothers were;

- They were much more timid.

- They didn’t know how to act with other monkeys.

- They were easily bullied and wouldn’t stand up for themselves.

- They had difficulty with mating.

- The females were inadequate mothers.

These behaviors were observed only in the monkeys who were left with the surrogate mothers for more than 90 days. For those left less than 90 days the effects could be reversed if placed in a normal environment where they could form attachments.

Harlow concluded that for a monkey to develop normally s/he must have some interaction with an object to which they can cling during the first months of life (critical period). Clinging is a natural response – in times of stress, the monkey runs to the object to which it normally clings as if the clinging decreases the stress. He also concluded that early maternal deprivation leads to emotional damage but that its impact could be reversed in monkeys if an attachment was made before the end of the critical period. However, if maternal deprivation lasted after the end of the critical period, then no amount of exposure to mothers or peers could alter the emotional damage that had already occurred. Harlow found therefore that it was social deprivation rather than maternal deprivation that the young monkeys were suffering from. When he brought some other infant monkeys up on their own, but with 20 minutes a day in a playroom with three other monkeys, he found they grew up to be quite normal emotionally and socially.

Harlow’s work has been criticized, and his experiments have been seen as unnecessarily cruel (unethical) and of limited value in attempting to understand the effects of deprivation on human infants. It was clear that the monkeys in this study suffered from emotional harm from being reared in isolation. This was evident when the monkeys were placed with a normal monkey (reared by a mother), they sat huddled in a corner in a state of persistent fear and depression. Also, Harlow created a state of anxiety in female monkeys which had implications once they became parents. Such monkeys became so neurotic that they smashed their infant’s face into the floor and rubbed it back and forth.

Harlow’s experiment is sometimes justified as providing a valuable insight into the development of attachment and social behavior. At the time of the research, there was a dominant belief that attachment was related to physical (i.e., food) rather than emotional care. It could be argued that the benefits of the research outweigh the costs (the suffering of the animals). For example, the research influenced the theoretical work of John Bowlby, the most important psychologist in attachment theory. It could also be seen a vital in convincing people about the importance of emotional care in hospitals, children’s homes, and daycare.[44]

Mary Ainsworth and the Strange Situation

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, continued studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth and her colleagues created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. The test is called The Strange Situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent (Ainsworth, 1979).

During the procedure, which lasts about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, and then the parent again enters and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviors, which are later coded by the research team. The investigators were especially interested in how the child responded to the caregiver leaving and returning to the room, referred to as the “reunion.” On the basis of their behaviors, the children are categorized into one of four groups where each group reflects a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. One style is secure and the other three styles are referred to as insecure.

- A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the caregiver is present and may engage with the stranger. The child will typically play with the toys and bring one to the caregiver to show and describe from time to time. The child may be upset when the caregiver departs but is also happy to see the caregiver return.

- A child with an ambivalent (resistant) attachment style is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the caregiver rather than exploring the toys. When the caregiver leaves, the child is extremely distressed and is ambivalent when the caregiver returns. The child may rush to the caregiver but then fails to be comforted when picked up. The child may still be angry and even resist attempts to be soothed.

- A child with an avoidant attachment style will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother.

- A child with a disorganized (disoriented) attachment style seems to have an inconsistent way of coping with the stress of the strange situation. The child may cry during the separation, but avoid the mother when she returns, or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor.

How common are the attachment styles among children in the United States? It is estimated that about 65 percent of children in the United States are securely attached. Twenty percent exhibit avoidant styles and 10 to 15 percent are ambivalent. Another 5 to 10 percent may be characterized as disorganized.

In the years that have followed Ainsworth’s ground-breaking research, researchers have investigated a variety of factors that may help determine whether children develop secure or insecure relationships with their primary attachment figures. One of the key determinants of attachment patterns is the history of sensitive and responsive interactions between the caregiver and the child. In short, when the child is uncertain or stressed, the ability of the caregiver to provide support to the child is critical for his or her psychological development. It is assumed that such supportive interactions help the child learn to regulate his or her emotions, give the child the confidence to explore the environment and provide the child with a safe haven during stressful circumstances.

Evidence for the role of sensitive caregiving in shaping attachment patterns comes from longitudinal and experimental studies. For example, Grossmann, Grossmann, Spangler, Suess, and Unzner (1985) studied parent-child interactions in the homes of 54 families, up to three times during the first year of the child’s life. At 12 months of age, infants and their mothers participated in the strange situation. Grossmann and her colleagues found that children who were classified as secure in the strange situation at 12 months of age were more likely than children classified as insecure to have mothers who provided responsive care to their children in the home environment.

Van den Boom (1994) developed an intervention that was designed to enhance maternal sensitive responsiveness. When the infants were 9 months of age, the mothers in the intervention group were rated as more responsive and attentive in their interaction with their infants compared to mothers in the control group. In addition, their infants were rated as more sociable, self-soothing, and more likely to explore the environment. At 12 months of age, children in the intervention group were more likely to be classified as secure than insecure in the strange situation.[45]

Attachment researchers have also studied the association between children’s attachment patterns and their adaptation over time. Researchers have learned, for example, that children who are classified as secure in the strange situation are more likely to have high-functioning relationships with peers, to be evaluated favorably by teachers, and to persist with more diligence in challenging tasks. In contrast, insecure-avoidant children are more likely to be construed as “bullies” or to have a difficult time building and maintaining friendships (Weinfield, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2008).[46]

Research on attachment in adolescence finds that teens who are still securely attached to their parents have fewer emotional problems (Rawatlal, Kliewer & Pillay, 2015), are less likely to engage in drug abuse and other criminal behaviors (Meeus, Branje & Overbeek, 2004), and have more positive peer relationships (Shomaker & Furman, 2009).[47]

Keep in mind that methods for measuring attachment styles have been based on a model that reflects middle-class, U. S. values and interpretation, some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2010). For example, German parents value independence and Japanese mothers are typically by their children’s sides. As a result, the rate of insecure-avoidant attachments is higher in Germany and insecure-resistant attachments are higher in Japan, and that these differences may reflect cultural variation rather than true insecurity. (van Ijzendoorn and Sagi, 1999).[48]

Attachment Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) classifies reactive attachment disorder (RAD) as a trauma- and -stressor-related condition of early childhood caused by social neglect and maltreatment. Affected children have difficulty forming emotional attachments to others, show a decreased ability to experience positive emotion, cannot seek or accept physical or emotional closeness and may react violently when held, cuddled, or comforted. Behaviorally, affected children are unpredictable, difficult to console, and difficult to discipline. Moods fluctuate erratically, and children may seem to live in a “flight, fight, or freeze” mode. Most have a strong desire to control their environment and make their own decisions. Changes in routine, attempts to control, or unsolicited invitations to comfort may elicit rage, violence, or self-injurious behavior. In the classroom, these challenges inhibit the acquisition of core academic skills and lead to rejection from teachers and peers alike.

As they approach adolescence and adulthood, socially neglected children are more likely than their neuro-typical peers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, have an involvement with the legal system, and experience incarceration

The genesis of reactive attachment disorder is always trauma; specifically, the severe emotional neglect commonly found in institutional settings, such as overcrowded orphanages, foster care, or in homes with mentally or physically ill parents. Over time, infants who do not develop a predictable, nurturing bond with a trusted caregiver, do not receive adequate emotional interaction and mental stimulation halt their attempts to engage others and turn inward, ceasing to seek comfort when hurt, avoiding physical and emotional closeness, and eventually become emotionally bereft. The absence of adequate nurturing results in poor language acquisition, and impaired cognitive development and contributes to behavioral dysfunction.

Since WWII, physicians, psychologists, and attachment theorists have documented the impact of social neglect on physical and emotional development. Experiments completed in the 1940s and 1950s found that maternal deprivation had a profound effect on infant growth, motor development, social interaction, and behavior. In the film Psychogenic Diseases in Infancy (Spitz, 1952), infants deviated from the normal, expected course of development and became “unapproachable, weepy and screaming” within the first 2 months of maternal deprivation. As the deprivation continued, facial expressions became rigid and then flat; motor development regressed, and by the fifth month, infants were “lethargic,” unable to “sit, stand, walk, or talk,” suffered from growth abnormalities, developed “atypical, bizarre finger movements,” and no longer sought or responded to social interaction; 37.3% of the infants died within 2 years. These early experiments became the foundation for Attachment Theory and outlined the constellation of symptoms of what the DSM, Third Edition (DSM–III) would later call reactive attachment disorder.

The DSM-5 gives the following criteria for reactive attachment disorder:

- “A consistent pattern of inhibited, emotionally withdrawn behavior toward adult caregivers, manifested by both of the following:

- The child rarely or minimally seeks comfort when distressed.

- The child rarely or minimally responds to comfort when distressed.

- A persistent social or emotional disturbance characterized by at least two of the following:

- Minimal social and emotional responsiveness to others

- Limited positive affect

- Episodes of unexplained irritability, sadness, or fearfulness are evident even during nonthreatening interactions with adult caregivers.

- The child has experienced a pattern of extremes of insufficient care as evidenced by at least one of the following:

- Social neglect or deprivation in the form of persistent lack of basic emotional needs for comfort, stimulation, and affection met by caring adults

- Repeated changes of primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments (e.g., frequent changes in foster care)

- Rearing in unusual settings that severely limit opportunities to form selective attachments (e.g., institutions with high child-to-caregiver ratios)

- The care in Criterion C is presumed to be responsible for the disturbed behavior in Criterion A (e.g., the disturbances in Criterion A began following the lack of adequate care in Criterion

- The criteria are not met for autism spectrum disorder.

- The disturbance is evident before age 5 years.

- The child has a developmental age of at least nine months.”

These diagnostic criteria provide an outline of symptoms; however, providers must also recognize the global impact on cognition, behavior, and affective functioning. Abuse in childhood has been correlated with difficulties in working memory and executive functioning, while severe neglect is associated with underdevelopment of the left cerebral hemisphere and the hippocampus. Social skills are below what would be expected of either their chronological age or developmental level. Children with RAD may respond to ordinary interactions with aggression, fear, defiance, or rage. Affected children are more likely to face rejection by adults and peers, develop a negative self-schema, and experience somatic symptoms of distress. Psychomotor restlessness is common, as is hyperactivity and stereotypic movements, such as hand flapping or rocking. RAD increases the risk of anxiety, depression, and hyperactivity, and reduces frustration tolerance. Ailing children are likely to be highly reactive, even in non-threatening situations.

Evaluation

Clinicians should have a low threshold for referring children with a known history of adoption, abuse, foster, or institutional care to a child psychologist or psychiatrist for a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment detailing the child’s history, a description of the symptoms over time, and direct observation of the parent-child interaction. Attachment behaviors and signs of secure attachment (e.g., comfort-seeking, good eye contact, child-initiated interaction) should be assessed at every visit. Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for referral to a child development specialist, a child psychiatrist, or a child psychologist.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of RAD requires a multi-pronged approach incorporating parent education and trauma-focused therapy. Parent education focused on developing positive, non-punitive behavior management strategies, ways of responding to nonverbal communication, anticipation and coping strategies for when triggers arise and parent-child psychotherapy can facilitate bonding and healthy attachment. Empathy and compassion are key elements to building trust. Developing a nurturing parent-child relationship is the cornerstone to overcoming the damage caused by severe neglect and abuse.

Prognosis

Even with intervention, injured children encounter difficulties in every aspect of their lives; from classroom learning to develop a secure sense of self. The traumatic situations which lead to the attachment disorder create a persistent state of stress that diminishes their capacity for resilience. Early identification and treatment have been shown to improve outcomes; however, parent education and support are key. Parents adopting children from state custody or from overseas orphanages should receive education on the impact of social deprivation and connect them with service agencies or providers specializing in attachment disorders.[49]

- Psychology 2e, Emotion and Motivation from Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- CC0 Public Domain ↵

- Image from wikipedia.org is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Matching Your Face or Appraising the Situation: Two Paths to Emotional Contagion by Huan Deng and Ping Hu retrieved from Frontiers in Psychology licensed under CC-BY 3.0. (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Socioemotional Development in Childhood Boundless Psychology. Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Psychology2e from Openstax licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0[11] Marshmallow Test Image retrieved from wiki How licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Psychology2e from Openstax licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Psychology2e from Openstax licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Emotional Intelligence by Lyndsay T Wilson retrieved from Explorable is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- The Relationship Between Trait Emotional Intelligence, Cognition, and Emotional Awareness: An Interpretative Model by Sergio Agnoli, Giacomo Mancini, Federica Andrei, and Elena Trombini retrieved from Frontiers in Psychology is licensed under CC BY-4.0. (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/features/anxiety-depression-children.html ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Image retrieved from Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Depression Basics from NIMH.NIH.gov is public domain ↵

- Depression in Children by Ali J. Alsaad; Yusra Azhar; Yasser Al Nasser retrieved from NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov is public domain (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Depression Basics from NIMH.NIH.gov is public domain ↵

- Depression in Children by Ali J. Alsaad; Yusra Azhar; Yasser Al Nasser retrieved from NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov is public domain (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Image is in the public domain and retrieved from Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes ↵

- Anxiety and Depression in Children retrieved from CDC.Gov – public domain ↵

- Hamill-Skoch S, Hicks P, Prieto-Hicks X. (2012) The use of cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents. From NIH National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. Licensed under Public Domain. ↵

- From: Family-Based Interpersonal Psychotherapy: An Intervention for Preadolescent Depression (2020) by Laura J. Dietz Ph.D.. Published in The American Journal of Psychotherapy. Licensed under Fair Use for academic purposes. ↵

- Anxiety and Depression in Children retrieved from CDC.Gov is public domain ↵

- Depression Basics from NIMH.NIH.gov is public domain ↵

- Text from PsychDB and adapted by Maria Pagano. No author name is provided. Licensed under Fair Use ↵

- From NIH National Library of Medicine. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Conduct Disorder in Females is Associated with Reduced Corpus Callosum Structural Integrity Independent of Comorbid Disorders and Exposure to Maltreatment (2016) by P. Linder, I. Savic, R. Sitnikov, M. Budhiraja, Y. Liu, J. Jokinen, J. Tiihonen, and S. Hodgins. Licensed under Public Domain ↵

- Text and text for table from PsychDB and adapted by Maria Pagano. No author name is provided. Licensed under Fair Use ↵

- Text from PsychDB and adapted by Maria Pagano. No author name is provided. Licensed under Fair Use ↵

- From Wikipedia: Multisystemic Therapy. Licensed under CC BY SA 3.0. Adapted by Maria Pagano ↵

- From NIH National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2015) Multisystemic Therapy for Externalizing Youth by Kristyn Zajac, Ph.D., Jeff Randall, Ph.D., and Cynthis Cupit Swenson, Ph.D. Licensed under Public Domain. ↵

- From Wikipedia: Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Licensed under CC BY SA 3.0. ↵

- Psychological Disorders retrieved from, Boundless Psychology / Curation and Revision: Provided by: Boundless.com licensed by CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Image retrieved from Pixabay - public domain (CC0) ↵

- From Wikipedia: Intermittent Explosive Disorder. Licensed under CC BY SA 3.0 ↵

- Text and illustration from CGS Psychology Blog" Mrs. Harris & Miss D'Cruz. No licensing information provided on blog. Text adapted by Maria Pagano ↵

- From Psych Teacher (UK) PsychTeacher: Making A level Psychology Easier. No author or licensing information provided on blog ↵

- Attachment theory. by McLeod, S. A. retrieved from Simply Psychology licensed under CC NY-NC-ND 3.0[34] Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Attachment theory. by McLeod, S. A. retrieved from Simply Psychology licensed under CC NY-NC-ND 3.0[34] Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Attachment Through the Life Course by R. Chris Fraley retrieved from NOBA licensed under CC BY-BC-SA 4.0. ↵

- Attachment Through the Life Course by R. Chris Fraley retrieved from NOBA licensed under CC BY-BC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology, by, Laura Overstreet. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. ↵

- Reactive Attachment Disorder by Elizabeth E. Ellis; Musa Yilanli; Abdolreza Saadabadi. retrieved from StatPearls Publishing NCBI.NLM.NIH.gov. Licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0 ↵