12 Development of the Self and Moral Development

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 12, you should be equipped to:

- Describe the development of self-concept and awareness of others.

- Understand the influence of nature and nurture on gender development.

- Describe the various theories of moral development

Development of Self-Concept

How does Self-Concept Emerge?

If you have ever observed an infant between the ages of 6-12 months look at themselves in a mirror you wouldn’t be surprised to find that the infant views his or her reflection as another person. This is because the child has yet to develop a sense of self or self-concept.[1]

Self-concept refers to beliefs about general personal identity (Seiffert, 2011). These beliefs include personal attributes, such as one’s age, physical characteristics, behaviors, and competencies. Children in middle and late childhood have a more realistic sense of self than do those in early childhood, and they better understand their strengths and weaknesses. This can be attributed to greater experience in comparing their own performance with that of others, and to greater cognitive flexibility. Children in middle and late childhood are also able to include other peoples’ appraisals of them into their self-concept, including parents, teachers, peers, culture, and media.[2]

We aren’t born with a self-concept. It develops through interaction with others. Usually, these others are those close to us like parents, siblings, or peers. Let’s look at two theories of self based on interaction.

Charles Horton Cooley used the metaphor of a mirror or looking-glass when describing this process. Our self-concept develops when we look at how those around us respond to us, how we look, what we say, and what we do. We then use their reactions to make self-judgments. If those around us respond favorably to us, we’ll form a positive sense of self. But if those around us respond with criticism and insult, we interpret that as evidence that we are not good or acceptable. But those around us may respond to us based on more than our own performance or worth. Perhaps they don’t notice what we do well or are reluctant to comment on it. As a result, we may have an inaccurate self-concept. And there may be certain periods in life in which we are more self-conscious or concerned with how others view us. Early childhood may be one of those times when children are piecing together a sense of self.

George Herbert Mead also focused on social interaction as important for developing a sense of self. He divided the self into two parts: the “I” or the spontaneous part of the self that is creative and internally motivated, and the “me” or the part of the self that takes into account what other people think. The key to living well is to find ways to give expression to the “I” with the approval of the “me”. In other words, find out how to be creative and do what you care about within the guidelines of society. The “I” is inborn. But the “me” develops through social interaction and a process called “taking the role of the other.” A child first comes to take the role of a significant other person, typically a parent or sibling. A child, who has been told not to do something, may be found saying “no” to himself. Gradually, the child will come to understand how the generalized other, or society at large, comes to view actions. Now a behavior is not just wrong according to a significant other person, it is wrong as a rule of society. In this way, cultural expectations become part of the judgment of self.

Mirror Recognition Test [3]

As previously discussed, we are not born with a self-concept or sense of self. So, when does one’s self-concept begin? Beulah Amsterdam (1972) was the first to study this question with humans. After placing a smudge of rouge surreptitiously on the nose of an infant, Amsterdam asked the child’s mother to point to a mirror and ask the child, “Who’s that?”

Based on the child’s response, Amsterdam found that children could be placed into one of three categories based on their age:

- 6-12 months: The child appeared to believe their refection was another child and, in some cases, tried to play with the “other” child.

- 13-24 months: Some infants in this group were a bit wary of the “other” child and withdrew, while some occasionally smiled.

- 20 months and older: Infants pointed or rubbed the rouge on their nose, leading Amsterdam to believe that this group had achieved self-concept.

The development of language also provides researchers with an insight into the developing self-concept. For example, between the ages of 15 and 18 months children will begin to use words such as “mine” and “my” indicating that they understand their relationship to a person or thing.

Early self-concepts can be quite exaggerated. A child may want to be the biggest or be able to jump the highest or have the longest hair. This exaggerated sense of self is external; the child emphasizes outward expressions and responses in developing a sense of self. Older children tend to become more realistic in their sense of self as they start comparing their own behavior with that of others.[4]

Preschoolers Self Concept

By the age of three or four, children begin to view themselves as separate and unique individuals capable of independent thoughts and actions. For example, in striving to become autonomous the 4-year-old may insist on dressing themselves. While this may take more patience on the part of parents it is important to allow the child to develop their autonomy. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being critical of messes or mistakes. Soggy washrags and toothpaste left in the sink pales in comparison to the smiling face of a five-year-old that emerges from the bathroom with clean teeth and pajamas![5]

When describing themselves, preschoolers limit their descriptions to concrete expressions such as their physical attributes, age, and sex.

School-Age Children’s Self Concept

The period of middle childhood is a time where the child becomes less egocentric and more able to think about themselves in complex ways. According to Erikson, during this time children are very busy or industrious. They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, and achieving. This is a very active time and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with friends. Erikson believed that if these industrious children can be successful in their endeavors, they will get a sense of confidence for future challenges. If not, a sense of inferiority can be particularly haunting during middle childhood.[6]

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the judgments and evaluations we make about our self- concept. While self-concept is a broad description of the self, self-esteem is a more specifically an evaluation of the self. Children can have individual assessments of how well they perform a variety of activities and also develop an overall global self-assessment. If there is a discrepancy between how children view themselves and what they consider to be their ideal selves, their self-esteem can be negatively affected.[7]

Self-Efficacy

Another important development in self-understanding is self-efficacy, which is the belief that you are capable of carrying out a specific task or of reaching a specific goal (Bandura, 1977, 1986, 1997). Large discrepancies between self-efficacy and ability can create motivational problems for the individual (Seifert, 2011). If a student believes that he or she can solve mathematical problems, then the student is more likely to attempt the mathematics homework that the teacher assigns. Unfortunately, the converse is also true. If a student believes that he or she is incapable of math, then the student is less likely to attempt the math homework regardless of the student’s actual ability in math. Since self-efficacy is self-constructed, it is possible for students to miscalculate or misperceive their true skills, and these misperceptions can have complex effects on students’ motivations. It is possible to have either too much or too little self-efficacy, and according to Bandura (1997), the optimum level seems to be either at or slightly above, true ability.[8]

If a person’s sense of self-efficacy is very low, he or she can develop learned helplessness, a perception of complete lack of control in mastering a task. The attitude is similar to depression, a pervasive feeling of apathy, and a belief that effort makes no difference and does not lead to success. Learned helplessness was originally studied from the behaviorist perspective of classical and operant conditioning by the psychologist Martin Seligman (1995). In people, learned helplessness leads to characteristic ways of dealing with problems. They tend to attribute the source of a problem to themselves, to generalize the problem to many aspects of life, and to see the problem as lasting or permanent. More optimistic individuals, in contrast, are more likely to attribute a problem to outside sources, to see it as specific to a particular situation or activity, and to see it as temporary or time-limited. Consider, for example, two students who each fail a test. The one with a lot of learned helplessness is more likely to explain the failure by saying something like: “I’m stupid; I never perform well on any schoolwork, and I never will perform well at it.” The other, more optimistic student is more likely to say something like: “The teacher made the test too hard this time, so the test doesn’t prove anything about how I will do next time or in other subjects.”

What is noteworthy about these differences in perception is how much the more optimistic of these perspectives resembles high self-efficacy and how much learned helplessness seems to contradict or differ from it. As already noted, high self-efficacy is a strong belief in one’s capacity to carry out a specific task successfully. By definition, therefore, self-efficacy focuses attention on a temporary or time-limited activity (the task), even though the cause of successful completion (oneself) is “internal.”[9]

Gender Development

Another important dimension of the self is the sense of self as male or female. Preschool-aged children become increasingly interested in finding out the differences between boys and girls both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While 2-year-olds can identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. This self-identification or gender identity is followed sometime later with gender constancy or the knowledge that gender does not change. Gender roles or the rights and expectations that are associated with being male or female are learned throughout childhood and into adulthood. [10]

Gender roles in play [11]

Theories of Gender Development

How do our gender roles and gender stereotypes develop and become so strong? Many of our gender stereotypes are so strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). For example, males and females are treated differently before they are even born. When someone learns of a new pregnancy, the first question typically asked is “Is it a boy or a girl?” Immediately upon hearing the answer, judgments are made about the child: Boys will be rough and like blue, while girls will be delicate and like pink.[12]

The development of gender and gender identity is likewise an interaction among social, biological, and representational influences (Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Young children learn about gender from parents, peers, and others in society, and develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness (called gender schemas). They also negotiate biological transitions (such as puberty) that cause their sense of themselves and their sexual identity to mature. There are several psychological theories that partially explain how children form their own gender roles after they learn to differentiate based on gender.[13]

Psychoanalytic Theories of Gender Development

Freud believed that masculinity and femininity were learned during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. During the phallic stage, the child develops an attraction to the opposite-sexed parent but after recognizing that that parent is unavailable, learns to model their own behavior after the same-sexed parent. The child develops his or her own sense of masculinity or femininity from this resolution. And, according to Freud, a person who does not exhibit gender-appropriate behavior, such as a woman who competes with men for jobs or a man who lacks self-assurance and dominance, has not successfully completed this stage of development. Consequently, such a person continues to struggle with his or her own gender identity.[14]

Chodorow, a neo-Freudian, believed that mothering promotes gender stereotypic behavior. Mothers push their sons away too soon and direct their attention toward problem-solving and independence. As a result, sons grow up confident in their own abilities but uncomfortable with intimacy. Girls are kept dependent too long and are given unnecessary and even unwelcome assistance from their mothers. Girls learn to underestimate their abilities and lack assertiveness but feel comfortable with intimacy.

Both models assume that early childhood experiences result in lifelong gender self-concepts. However, gender socialization is a process that continues throughout life. Children, teens, and adults refine and can modify their sense of self based on gender.[15]

Social Learning Theory

Learning theorists suggest that gender role socialization is a result of the ways in which parents, teachers, friends, schools, religious institutions, media, and others send messages about what is acceptable or desirable behavior as males or females. This socialization begins early-in fact, it may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and potential on the part of a parent. And this stereotyping continues to guide perception throughout life. Consider parents of newborns, shown a 7-pound, 20-inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying. (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Female infants are held more, talked to more frequently, and given direct eye contact, while male infants’ play is often mediated through a toy or activity.

Sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home such as cleaning or cooking that is performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems and daughters are more likely to be given assistance even when they are working on an answer. This impatience is reflected in teachers waiting less time when asking a female student for an answer than when asking for a reply from a male student (Sadker and Sadker, 1994). Girls are given the message from teachers that they must try harder and endure in order to succeed while boys’ successes are attributed to their intelligence. Of course, the stereotypes of advisors can also influence which kinds of courses or vocational choices girls and boys are encouraged to make.

Friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls and popularity may be based on modeling what is considered ideal behavior or looks for the sexes. Girls tend to tell one another secrets to validate others as best friends while boys compete for positions by emphasizing their knowledge, strength, or accomplishments. This focus on accomplishments can even give rise to exaggerating accomplishments in boys, but girls are discouraged from showing off and may learn to minimize their accomplishments as a result.

Gender messages abound in our environment. But does this mean that each of us receives and interprets these messages in the same way? Probably not. In addition to being recipients of these cultural expectations, we are individuals who also modify these roles (Kimmel, 2008).[16]

Cognitive Theory

Unlike Social Learning theory that is based on external rewards and punishments, Cognitive Learning theory states that children develop gender at their own levels. The 3 stage model (See table below), formulated by Kohlberg, asserts that at Stage 1 (2-3 years), children recognize their own gender, but the gender identity of others is based on outward appearance, so if that child sees someone with short hair that person will be labeled a boy. During Stage 2, gender stability occurs, and while the child recognizes that their own gender is stable over time (i.e. a girl will grow up to be a mommy), that same child is not sure about others, so if the child observes a boy playing with a doll, that child will think that the boy will grow up to be a woman. By Stage 3 gender becomes relatively fixed or constant, and the child understands that gender is consistent across all situations they might encounter. Kohlberg also believed that this during this stage identity marker were produced that provided children with a schema (A set of observed or spoken rules for how social or cultural interactions should happen.) in which to organize much of their own behavior and the behavior of others, and that children looked for role models to emulate maleness or femaleness as they grow older.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Gender Development

Stage 1. Gender Identity:

At approximately ages 2 to 3, the child recognizes that they are a girl or a boy and will also recognize and label others as a girl or a boy. However, that label of “girl” or “boy” is based solely on that other child’s outward appearance. Therefore, a child at this stage who sees a child with long hair would label that child as a girl even if it were a boy.

Stage 2. Gender Stability:

By 3 years of age, children recognize that their own gender is stable over time. That is a boy will grow into a man and a girl will grow into a woman. However, this same child is still unsure about others. For example, a child in this stage would believe that a girl who plays with trucks would grow up to be a man. So, while the child in this stage understands gender from their own perspective, they do not understand gender from another’s perspective.

Stage 3. Gender Constancy:

By the age of 5 or 6 children understand that gender is consistent across all situations, so just because a boy may play with a doll, he will remain a boy.

Although influential, Kohlberg’s theory tends to be descriptive rather than explanatory. The theory describes how a child’s thinking regarding gender changes as they get older. However, the theory fails to explain why gender schemas change with age. What is affecting the child’s schemas/thinking to change over time? [17]

Gender Schema Theory

Gender schema theory argues that children are active learners who essentially socialize themselves. In this case, children actively organize others’ behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories, which are known as schemas. These schemas then affect what children notice and remember later. People of all ages are more likely to remember schema-consistent behaviors and attributes than schema-inconsistent behaviors and attributes. So, people are more likely to remember men, and forget women, who are firefighters. They also misremember schema-inconsistent information. If research participants are shown pictures of someone standing at the stove, they are more likely to remember the person to be cooking if depicted as a woman, and the person to be repairing the stove if depicted as a man. By only remembering schema-consistent information, gender schemas strengthen more and more over time.[18]

Gender Socialization

Treating boys and girls differently is both a consequence of gender differences and a cause of gender differences and begins with parents. A meta-analysis of research from the United States and Canada found that parents most frequently treated sons and daughters differently by encouraging gender-stereotypical activities (Lytton & Romney, 1991). Fathers, more than mothers, are particularly likely to encourage gender-stereotypical play, especially in sons. Parents also talk to their children differently based on stereotypes. For example, parents talk about numbers and counting twice as often with sons than with daughters (Chang, Sandhofer, & Brown, 2011) and talk to sons in more detail about science than with daughters. Parents are also much more likely to discuss emotions with their daughters than their sons.

Children do a large degree of socializing themselves. By age 3, children play in gender-segregated play groups and expect a high degree of conformity. Children who are perceived as gender-atypical (i.e., do not conform to gender stereotypes) are more likely to be bullied and rejected than their more gender-conforming peers.

In recent years, gender and related concepts have become a common focus of social change and social debate. Many societies, including American society, have seen a rapid change in perceptions of gender roles, media portrayals of gender, and legal trends relating to gender. For example, there has been an increase in children’s toys attempting to cater to both genders (such as Legos marketed to girls), rather than catering to traditional stereotypes. Nationwide, the acceptance of homosexuality and gender questioning has resulted in a rapid push for legal change to keep up with social change. [19]

How Much Does Gender Matter for Children?

Starting at birth, children learn the social meanings of gender from adults and their culture. Gender roles and expectations are especially portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music (Khorr, 2017). Therefore, when children make choices regarding their gender identification, expression, and behavior that may be contrary to gender stereotypes, it is important that they feel supported by the caring adults in their lives. This support allows children to feel valued, resilient, and develop a secure sense of self (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2015).[20]

Moral Development

Morality is a system of beliefs about what is right and good compared to what is wrong or bad. Moral development is the process whereby children develop an understanding of the proper attitudes and behaviors toward other people in society based on social and cultural norms, rules, and laws.[21] Moral beliefs are related to, but not identical with, moral behavior: it is possible to know the right thing to do, but not actually do it. It is also not the same as knowledge of social conventions, which are arbitrary customs needed for the smooth operation of society. Social conventions may have a moral element, but they have a primarily practical purpose. Conventionally, for example, motor vehicles all keep to the same side of the street (to the right in the United States, to the left in Great Britain). The convention allows for the smooth, accident-free flow of traffic. But following the convention also has a moral element, because an individual who chooses to drive on the wrong side of the street can cause injuries or even death. In this sense, choosing the wrong side of the street is wrong morally, though the choice is also unconventional.

When it comes to schooling and teaching, moral choices are not restricted to occasional dramatic incidents but are woven into almost every aspect of classroom life. Imagine this simple example. Suppose that you are teaching, reading to a small group of second graders, and the students are taking turns reading a story out loud. Should you give every student the same amount of time to read, even though some might benefit from having additional time? Or should you give more time to the students who need extra help, even if doing so bores classmates and deprives others of equal shares of “floor time”? Which option is more fair, and which is more considerate? Simple dilemmas like this happen every day at all grade levels simply because students are diverse, and because class time and a teacher’s energy are finite.

Embedded in this rather ordinary example are moral themes about fairness or justice, on the one hand, and about consideration or care on the other. It is important to keep both themes in mind when thinking about how students develop beliefs about right or wrong. A morality of justice is about human rights—or more specifically, about respect for fairness, impartiality, equality, and individuals’ independence. A morality of care, on the other hand, is about human responsibilities—more specifically, about caring for others, showing consideration for individuals’ needs, and interdependence among individuals. Students and teachers need both forms of morality. In the next sections, therefore, we explain a major example of each type of developmental theory, beginning with the morality of justice.[22]

Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development

Piaget based his theory of moral development on the patterns of reasoning used by children of different ages about moral decisions. These moral decisions made by children were based on short stories or “vignettes” told to the children who were then asked questions about who the child believed was naughtier. For example,

1a. A little boy called John is in his room. He is called to dinner. He goes into the dining room. But behind the door, there was a chair, and on the chair, there was a tray with fifteen cups on it. John could not have known that there was all this behind the door. He goes in, the door knocks against the tray, bang go the fifteen cups and they all get broken!

1b. Once there was a little boy whose name was Henry. One day when his mother was out, he tried to get some jam out of the cupboard. He climbed up onto a chair and stretched out his arm. But the jam was too high, and he couldn’t reach it and have any. But while he was trying to get it he knocked over a cup. The cup fell down and broke.[23]

The following dialog represents the typical 6-year-old’s response and the typical 9-year-old’s response to the teacup story:

6-year-old Response:

Piaget: Have you understood these stories?

6-year-old: Yes.

Piaget: What did the first boy do?

6-year-old: He broke 11 cups.

Piaget: And the second one?

6-year-old: He broke a cup moving roughly.

Piaget: Why did the first one break the cups?

6-year-old: Because the door knocked them.

Piaget: And the second?

6-year-old: He was clumsy. When he was getting the jam the cup fell down.

Piaget: Is one of the boys naughtier than the other?

6-year-old: The first is because he knocked over 12 cups.

Piaget: If you were the daddy, which one would you punish most?

6-year-old: The one who broke 12 cups.

Piaget: Why did he break them?

6-year-old: The door shut too hard and he knocked them. He didn’t do it on purpose.

Piaget: And why did the other boy break a cup?

6-year-old: He wanted to get jam. He moved too far. The cup got broken.[24]

9-year-old Response:

Piaget: Which boy is naughtiest?

9-year-old: Well, the one who broke them as he was coming isn’t naughty, ‘cos he didn’t know there was any cups. The other one wanted to take the jam and caught his arm on a cup.

Piaget: Which one is the naughtiest?

9-year-old: The one who wanted to take the jam.

Piaget: How many cups did he break?

9-year-old: One.

Piaget: And the other boy?

9-year-old: Fifteen.

Piaget: Which one would you punish most?

9-year-old The boy who wanted to take the jam. He did it on purpose.[25]

Up until the age of about 2, Piaget (1965) believed that infants and children were premoral and had no conscious awareness of rules or morality. However, based on his interviews with older children Piaget consistently found that children younger than 7 tend to view the child who broke more cups as being naughtier than the child who broke fewer cups. However, by 8 years of age, the child begins to understand that one’s intentions are an important factor when judging morality.

Piaget (1965) suggested two main types of moral thinking:

- Heteronomous morality (moral realism) (4 to 7 years)

- Autonomous morality (moral relativism) (Begins by age 7 or 8)

Heteronomous Morality

Younger children, according to Piaget reasoned about morality in a way that was heteronomous, or subject to the control of others such as parents, teachers, and even God. In addition, these authority figures have the ability to impose punishment based on their power over the child. This type of thinking is also egocentric, in that the younger child cannot see the situation from different points of view, therefore intent is meaningless in the younger child’s determination of who is naughtier.

Another aspect of heteronomous thinking is immanent justice or the idea that automatic punishments come to someone based on their prior bad behavior or deed. For example in one moral dilemma posed to children, Piaget notes how children in this stage believe that a boy who stole apples then ran away only to fall through a rotting bridge into the water, fell through the bridge because he stole the apples. In other words, his fall was causally related to his bad deed and was a punishment for what he had done. [26]

Autonomous Morality

This second stage sees the child move away from being egocentric and consequently begins to understand the broader perspective of another as well as their intentions. The child also understands that rules are arbitrary constructs that are created by mutual consent for reasons of fairness and that following these rules is beneficial to them when interacting with others.[27]

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

One of the best-known explanations of how the morality of justice develops was developed by Lawrence Kohlberg and his associates (Kohlberg, Levine, & Hewer, 1983; Power, Higgins, & Kohlberg, 1991). To explore this area, he read the following moral dilemma to boys of different age groups:

A woman was on her deathbed. There was one drug that doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to produce. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000 which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man’s laboratory to steal the drug for his wife. Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?

What is important in terms of the answer is not whether you replied, “Yes, I would steal the drug,” or “No, I would not steal the drug,” but rather your rationale for the answer.

Based on participants’ responses Kohlberg developed a three-level (preconventional, conventional, and postconventional), six-stage (two stages for each level) theory of moral development whereby individuals experience the stages universally and in sequence as they form beliefs about justice. [28]

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Preconventional Level

At the preconventional level, a child’s sense of morality is externally controlled. A child accepts that a rule is a rule simply because someone in authority says so. Any behavior that results in punishment is deemed as bad, whereas any behavior that results in a reward is deemed as good.

Stage 1: Punishment and Obedience – In this stage, children find it hard to distinguish between two separate moral points of view, especially in a moral dilemma. The focus continues to be on behaving according to adult rules and avoiding punishment.

Stage 2: Instrumental Purpose – In this stage, children start to understand people can have conflicting moral views in the same situation; however, they view the “right” choice as the choice that has the most benefit for themselves rather than others.

Conventional Level

At the conventional level, children still believe they should follow rules, but not only for themselves. Rather, rules should be followed to maintain social order and keep positive relationships among others.

Stage 3: Interpersonal Cooperation – In this stage, children want to obey rules because “that’s what a good person should do. ” They focus on maintaining positive relationships with others, and they believe a good person should be trustworthy, loyal, and respectful. The main idea in this stage is following the Golden Rule – “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. ”

Stage 4: Social-order maintenance – In this stage, a child begins to look at the bigger picture of the world and how rules impact it. Rules should be enforced in the same way for all people; equality plays a large role in morality. Children believe all people play a role in upholding and maintaining social order.

Postconventional or Principled Level

At the postconventional or principled level, children can think of morals and values in an abstract way and begin to realize some moral dilemmas do not have a clear-cut, right or wrong answer.

Stage 5: Social contract – In this stage, children start to see the flexibility of rules and can imagine alternative situations. The social contract orientation believes that a person follows (or breaks) a rule because it brings about more good than harm in the long run.

Stage 6: Universal ethical principle – In this stage, a child believes the right action is the one chosen by his or her conscience and what is in the best interest of a person, regardless of the legality. Children begin to consider how a law (or breaking a law) would impact a person’s life, values, and self-worth.[29]

Summary and Examples of Responses for Each Stage[30]

| Age | Moral Level | Description |

| Young children prior to Age 9 | Preconventional Morality | Stage 1: Focus is on self-interest and punishment is avoided. The man shouldn’t steal the drug, as he may get caught and go to jail.

Stage 2: Rewards are sought. A person at this level will argue that the man should steal the drug because he does not want to lose his wife who takes care of him. |

| Older children, adolescents, and most adults | Conventional morality | Stage 3: Focus is on how situational outcomes impact others and wanting to please and be accepted. The man should steal the drug because that is what good husbands do.

Stage 4: People make decisions based on laws or formalized rules. Man should obey the law because stealing is a crime. |

| Rare in adolescents and few adults | Postconventional morality | Stage 5: Individuals employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviors and make it clear that while they do not generally favor breaking the law, laws are social contracts that we agree to until we can change them by democratic means. The man should steal the drug because laws can be unjust, and you have to consider the whole situation. Moral rights must be protected.

Stage 6: Moral behavior is based on self-chosen ethical principles that should look to settle disputes through the principles of justice that require each of us to impartially consider and respect the rights of all who are involved. Finding an answer to this question is not easy, and for this reason, Kohlberg actually dropped this stage from his scoring. |

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, people may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is frequently little correlation between how we score on the moral stages and how we behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of males better than it describes that of females (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). One of Kohlberg’s students, Carol Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence for a gender difference in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).[31]

Carol Gilligan and the Morality of Care

Carol and James Gilligan [32]

As logical as they sound, Kohlberg’s stages of moral justice are not sufficient for understanding the development of moral beliefs. To see why this is, suppose that you have a student who asks for an extension of the deadline for an assignment. The justice orientation of Kohlberg’s theory would prompt you to consider issues of whether granting the request is fair. Would the late student be able to put more effort into the assignment than other students? Would the extension place a difficult demand on you since you would have less time to mark the assignments? These are important considerations related to the rights of students and the teacher. In addition to these, however, are considerations having to do with the responsibilities that you and the requesting student have for each other and for others. Does the student have a valid personal reason (illness, death in the family, etc.) for the assignment being late? Will the assignment lose its educational value if the student has to turn it in prematurely? These latter questions have less to do with fairness and rights, and more to do with taking care of and responsibility for students. They require a framework different from Kohlberg’s to be understood fully.

One such framework has been developed by Carol Gilligan, whose ideas center on the morality of care, or a system of beliefs about human responsibilities, care, and consideration for others. Gilligan proposed three moral positions that represent different extents or breadth of ethical care. Unlike Kohlberg, Piaget, or Erikson, she does not claim that the positions form a strictly developmental sequence, but only that they can be ranked hierarchically according to their depth or subtlety. In this respect, her theory is “semi-developmental” in a way similar to Maslow’s theory of motivation (Brown & Gilligan, 1992; Taylor, Gilligan, & Sullivan, 1995). The table below summarizes the three moral positions from Gilligan’s theory:

Positions of Moral Development According to Gilligan

| Moral Position | Definition of What is Morally Good |

| Position 1: Survival orientation | Action that considers one’s personal needs only |

| Position 2: Conventional care | Action that considers others’ needs or preferences, but not one’s own |

| Position 3: Integrated care | Action that attempts to coordinate one’s own personal needs with those of others. |

Position 1: Survival Orientation

The most basic kind of caring is a survival orientation, in which a person is concerned primarily with his or her own welfare. If a teenage girl with this ethical position is wondering whether to get an abortion, for example, she will be concerned entirely with the effects of the abortion on herself. The morally good choice will be whatever creates the least stress for herself and that disrupts her own life the least. Responsibilities to others (the baby, the father, or her family) play little or no part in her thinking.

As a moral position, a survival orientation is obviously not satisfactory for classrooms on a widespread scale. If every student only looked out for himself or herself, classroom life might become rather unpleasant! Nonetheless, there are situations in which focusing primarily on yourself is both a sign of good mental health and relevant to teachers. For a child who has been bullied at school or sexually abused at home, for example, it is both healthy and morally desirable to speak out about how bullying or abuse has affected the victim. Doing so means essentially looking out for the victim’s own needs at the expense of others’ needs, including the bully’s or abuser’s. Speaking out, in this case, requires a survival orientation and is healthy because the child is taking care of themself.

Position 2: Conventional Caring

A more subtle moral position is conventional caring (caring for others), in which a person is concerned about others’ happiness and welfare, and about reconciling or integrating others’ needs where they conflict with each other. In considering an abortion, for example, the teenager at this position would think primarily about what other people prefer. Do the father, her parents, and/or her doctor want her to keep the child? The morally good choice becomes whatever will please others the best. This position is more demanding than Position 1, ethically and intellectually, because it requires coordinating several persons’ needs and values. But it is often morally insufficient because it ignores one crucial person: the self.

In classrooms, students who operate from Position 2 can be very desirable in some ways; they can be eager to please, considerate, and good at fitting in and at working cooperatively with others. Because these qualities are usually welcome in a busy classroom, teachers can be tempted to reward students for developing and using them. The problem with rewarding Position 2 ethics, however, is that doing so neglects the student’s development—his or her own academic and personal goals or values. Sooner or later, personal goals, values, and identity need attention and care, and educators have a responsibility for assisting students to discover and clarify them.

Position 3: Integrated Caring

The most developed form of moral caring in Gilligan’s model is integrated caring, the coordination of personal needs and values with those of others. Now the morally good choice takes account of everyone including yourself, not everyone except yourself. In considering an abortion, a woman at Position 3 would think not only about the consequences for the father, the unborn child, and her family but also about the consequences for herself. How would bearing a child affect her own needs, values, and plans? This perspective leads to moral beliefs that are more comprehensive but ironically are also more prone to dilemmas because the widest possible range of individuals are being considered.

In classrooms, integrated caring is most likely to surface whenever teachers give students wide, sustained freedom to make choices. If students have little flexibility about their actions, there is little room for considering anyone’s needs or values, whether their own or others. If the teacher says simply: “Do the homework on page 50 and turn it in tomorrow morning,” then the main issue becomes compliance, not a moral choice. But suppose instead that she says something like this: “Over the next two months, figure out an inquiry project about the use of water resources in our town. Organize it any way you want—talk to people, read widely about it, and share it with the class in a way that all of us, including yourself, will find meaningful.” An assignment like this poses moral challenges that are not only educational but also moral since it requires students to make value judgments. Why? For one thing, students must decide what aspect of the topic really matters to them. Such a decision is partly a matter of personal values. For another thing, students have to consider how to make the topic meaningful or important to others in the class. Third, because the timeline for completion is relatively far in the future, students may have to weigh personal priorities (like spending time with friends or family) against educational priorities (working on the assignment a bit more on the weekend). As you might suspect, some students might have trouble making good choices when given this sort of freedom—and their teachers might therefore be cautious about giving such an assignment. But the difficulties in making choices are part of Gilligan’s point: integrated caring is indeed more demanding than caring based only on survival or on consideration of others. Not all students may be ready for it.[33]

Social Domain Theory

Like the theories of Piaget, Kohlberg, and Gilligan, Social domain theory adopts the premise that children actively construct ways of understanding their world. However, unlike these theories moral development is viewed in terms of the individual’s interactions with their environment, and that moral reasoning is a separate domain of social knowledge. According to Turiel (1983) there are three domains of knowledge, the moral (how individuals should treat one another), the societal (conventions designed to foster the functioning of social groups which can vary from culture to culture), and the personal (matters of individual choice that do not affect others). Each of these domains is independent and develops in early childhood. Consequently, children as young as four years of age can evaluate and assess not only their own moral behavior but the behavior of others.[34]

In the tradition of Piaget and Kohlberg social domain researchers also ask children probing questions regarding the moral transgressions of others after having been presented with stories that reflect a moral indiscretion. However, unlike Piaget and Kohlberg, follow questions such as, “Would it still be wrong to do “X” behavior even if there was no rule about it?” are asked. Research from such studies has consistently revealed that children as young as 4 understand the difference between situations that are moral in nature (i.e. taking something that is not yours is always wrong) versus situations that are social in nature (i.e. It’s not polite to cut in front of the line), versus situation that are personal in nature (i.e. I don’t like loud discussion, but if someone else does then that’s their choice).[35]

Moral Development in the Family

In the formation of children’s morals, no outside influence is greater than that of the family. Through punishment, reinforcement, and both direct and indirect teaching, families instill morals in children and help them to develop beliefs that reflect the values of their culture. Although families’ contributions to children’s moral development are broad, there are particular ways in which morals are most effectively conveyed and learned.

Justice

Families establish rules for right and wrong behavior, which are maintained through positive reinforcement and punishment. Positive reinforcement is the reward for good behavior and helps children learn that certain actions are encouraged above others. Punishment, by contrast, helps to deter children from engaging in bad behaviors, and from an early age helps children to understand that actions have consequences. This system additionally helps children to make decisions about how to act, as they begin to consider the outcomes of their own behavior.

Fairness

The notion of what is fair is one of the central moral lessons that children learn in the family context. Families set boundaries on the distribution of resources, such as food and living spaces, and allow members different privileges based on age, gender, and employment. The way in which a family determines what is fair affects children’s development of ideas about rights and entitlements, and also influences their notions of sharing, reciprocity, and respect.

Personal Balance

Through understanding principles of fairness, justice, and social responsibilities, children learn to find a balance between their own needs and wants and the interests of the greater social environment. By placing limits on their own individual desires, children benefit from a greater sense of love, security, and shared identity. At the same time, this connectedness helps children to refine their own moral system by providing them with a reference for understanding right and wrong.

Social Roles

In the family environment, children come to consider their actions not only in terms of justice but also in terms of emotional needs. Children learn the value of social support from their families and develop motivations based on kindness, generosity, and empathy, rather than on only personal needs and desires. By learning to care for the interests and well-being of their family, children develop concern for society.[36]

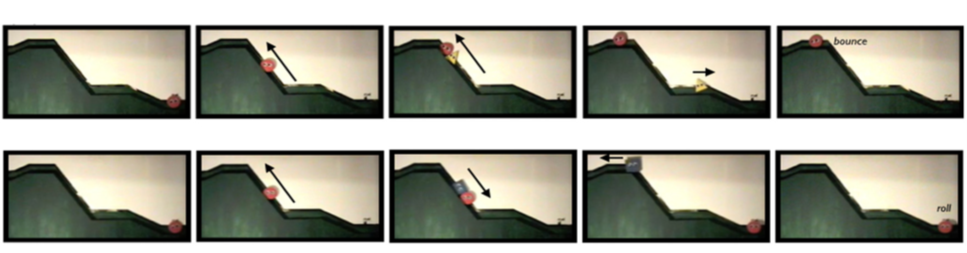

Are We Born Moral? Helpers and Hinderers

In a 2007 Hamlin, Wynn, and Bloom provided the first evidence that preverbal infants at 6 and at 10 months of age evaluate others on the basis of their helpful and unhelpful actions toward unknown third parties using what they called a “hill paradigm.” All events began with a “Climber” (most commonly a red, circular wooden character with large plastic ‘googly’ eyes) resting at the bottom of a hill containing two inclines, one shallow and one steep. To imply that the Climber’s goal was to reach the top of the hill, the googly portions of the Climber’s eyes were fixed diagonally upward such that he “gazed” uphill during the entirety of each event. “Helpers” and “Hinderers” were most commonly a blue square and a yellow triangle (whose googly eyes remained moveable); whether the square or the triangle was the Helper was counterbalanced

across infants.

At the start of both Helper and Hinderer events, the Climber first moved easily up the shallow incline to a landing where he wiggled back and forth. He then made two unsuccessful attempts to climb the steeper incline; on his first attempt he made it 1/3 of the way up before coming back down and on his second attempt he made it 2/3 of the way. To imply the Climber’s movements up and down the hill reflected a failed intention to climb to the top, during each ascent the Climber decelerated as though fighting upward against gravity, while during each descent he accelerated as though falling down with gravity. On the Climber’s third attempt, Helper and Hinderer events diverged. During Helper events, the Helper entered the scene from the bottom of the hill and bumped the Climber up from below twice, pushing him to the top of the steep incline. The Climber then bounced up and down for several seconds (as though happy to have achieved his goal) and the Helper moved back down the hill and offstage. During Hinderer events, the Hinderer entered the scene from the top of the hill and bumped the Climber down from above twice, forcing him to the bottom of the steep incline. The Climber then rolled end-over-end to the very bottom of the hill and the Hinderer moved back up the hill and offstage. Infants viewed alternating Helper and Hinderer events until a pre-set habituation criterion was reached. Following habituation, infants were presented with soft, stuffed, doll images of the the Helper and Hinderer to reach for. Both 6- and 10-month-olds selectively reached for the Helper, leading Hamlin, Wynn, and Bloom (2007) to conclude that the infants had based their decisions on a preference for those who performed positive social acts over those who performed negative social acts, and that this preference formed the basis for the development of later moral cognition [37]

- Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K., & Bloom, P. (2007). Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature, 450(7169), 557–559. Retrieved from Google Scholar ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0[3] Lecture Transcript Module 5 Early Childhood Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Image retrieved from Wikipedia is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Child Development – Unit 5: Theories (Part II) by Lumen Learning references Educational Psychology by Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton, licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Image by Amanda Westmont is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0[19]Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0[22] Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- From Lumen Learning Introduction to Communication. Cited as Survey of Communication Study. Authored by: Scott T Paynton and Linda K Hahn. Provided by: Humboldt State University. Located at: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Survey_of_Communication_Study/Preface. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0. ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Enter your footnote content here. Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Educational Psychology by Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton is licensed under CC BY 4.0. However, the link for the text is broken. The text with citation can be found at OER Services ↵

- Piaget, J. (1965). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Glencoe, Illinois. Public domain. ↵

- Piaget, J. (1965). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Glencoe, Illinois. Public domain. ↵

- Piaget, J. (1965). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Glencoe, Illinois. Public domain. ↵

- Piaget, J. (1965). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Glencoe, Illinois. Public domain. ↵

- The Moral Judgment of the Child ↵

- Child and Adolescent Psychology Lumen Learning licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- Image was retrieved from wikiwand.com and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Educational Psychology by Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . However, the link for the text is broken. The text with citation can be found at OER Services ↵

- Turiel, E. (1983). The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention (Cambridge studies in social and emotional development). New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Lourenco, O. (2014). Domain theory: A critical review. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 1-17. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259130460_Domain_theory_A_critical_review ↵

- Child and Adolescent Psychology Lumen Learning licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

- from Hamlin, J.K. (2015) Front. Psychol., 29 January 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01563 is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). (modified by Maria Pagano) ↵

one’s description and evaluation of oneself, including psychological and physical characteristics, qualities, skills, roles and so forth. Self-concepts contribute to the individual’s sense of identity over time.

the degree to which the qualities and characteristics contained in one’s self-concept are perceived to be positive.

an individual’s subjective perception of his or her capability to perform in a given setting or to attain desired results

a condition in which a person suffers from a sense of powerlessness, arising from a traumatic event or persistent failure to succeed.

one’s self-identification as male or female

the pattern of behavior, personality traits, and attitudes that define masculinity or femininity in a particular culture. It frequently is considered the external manifestation of the internalized gender identity

the understanding that one’s own or other people’s maleness or femaleness does not change over time

a child’s emerging sense of the permanence of being a boy or a girl, an understanding that occurs in a series of stages

the organized set of beliefs and expectations that guides one’s understanding of maleness and femaleness

a system of beliefs or set of values relating to right conduct, against which behavior is judged to be acceptable or unacceptable

of, relating to, or suggestive of a time before the development of a personal or social moral code : not having, showing, or involving an understanding of right and wrong

the type of thinking characteristic of younger children, who equate good behavior with obedience just as they equate the morality of an act only with its consequences.

the belief that the morality or immorality of an action is determined by social custom rather than by universal or fixed standards of right and wrong

the first level of moral reasoning, characterized by the child’s evaluation of actions in terms of material consequences. This level is divided into two stages: the earlier punishment and obedience orientation (Stage 1 in Kohlberg’s overall theory), in which moral behavior is that which avoids punishment; and the later naive hedonism (or instrumental relativist orientation; Stage 2), in which moral behavior is that which obtains reward or serves one’s needs

the intermediate level of moral reasoning, characterized by an individual’s identification with and conformity to the expectations and rules of family and society: The individual evaluates actions and determines right and wrong in terms of other people’s opinions. This level is divided into two stages: the earlier interpersonal concordance (or good-boy-nice-girl orientation, Stage 3 in Kohlberg’s overall theory), in which moral behavior is that which obtains approval and pleases others; and the later law-and-order (or authority and social order maintaining) orientation (Stage 4), in which moral behavior is that which respects authority, allows the person to do his or her duty, and maintains the existing social orde

the third and highest level of moral reasoning, characterized by an individual’s commitment to moral principles sustained independently of any identification with family, group, or country. This level is divided into two stages: the earlier social contract orientation (Stage 5 in Kohlberg’s overall theory), in which moral behavior is that which demonstrates an understanding of social mutuality, balancing general individual rights with public welfare and democratically agreed upon societal rights; and the later ethical principle orientation (Stage 6), in which moral behavior is based upon self-chosen, abstract ethical standards

Focus is on the needs of oneself. The survival of oneself is of sole concern

the focus is on the needs of others.

the focus is on the universal obligation of caring.

a theory of moral psychology that examines social reasoning and behavior from a developmental perspective