8 Cognitive Development: Information Processing, Memory, Executive Function, and Metacognition

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 8, you should be better equipped to:

- Describe the development of Information Processing

- Understand how attention develops in infancy and childhood

- Define attention deficit disorder

- Comprehend theories of memory and the development of memory in infancy and childhood

- Define and explain executive function

- Understand metacognition

Information Processing Theory

Information Processing is not the work of a single theorist but is based on the ideas and research of several cognitive scientists studying how individuals perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information. This approach assumes that humans gradually improve in their processing skills; that is, cognitive development is continuous rather than stage-like. The more complex mental skills of adults are built from the primitive abilities of children. We are born with the ability to notice stimuli, store, and retrieve information, and brain maturation enables advancements in our information processing system. At the same time, interactions with the environment also aid in our development of more effective strategies for processing information.[1]

Attention

Changes in attention have been described by many as the key to changes in human memory (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). However, attention is not a unified function; it is comprised of sub-processes. The ability to switch our focus between tasks or external stimuli is called divided attention or multitasking. This is separate from our ability to focus on a single task or stimulus, while ignoring distracting information, called selective attention. Different from these is sustained attention, or the ability to stay on task for long periods of time. Moreover, we also have attention processes that influence our behavior and enable us to inhibit a habitual or dominant response and others that enable us to distract ourselves when upset or frustrated.[2]

Attention in Infancy

An approach to understanding cognitive development by observing the behavior of infants is through the use of the habituation technique, which was discussed in detail in Chapter 2, Research Methods. You should recall that habituation refers to the decreased responsiveness toward a stimulus after it has been presented numerous times in succession. Organisms including infants, tend to be more interested in things the first few times they experience them and become less interested in them with more frequent exposure. Developmental psychologists have used this general principle to help them understand what babies remember and understand. Although this procedure is very simple, it allows researchers to create variations that reveal a great deal about a newborn’s cognitive ability.[3]

The results of visual habituation research and the findings from other studies that measured attention utilizing other measures (e.g., looking measures such as the visual paired comparison task, heart rate, and event-related potentials ) indicate a significant developmental change in sustained attention and selective attention across the infancy period. For example, infants show gains in the magnitude of the attention-related response and spend a greater proportion of time engaged in attention with increasing age (Richards and Turner, 2001). Throughout infancy, attention has a significant impact on infant performance on a variety of tasks tapping into recognition memory.[4]

Attention in Childhood

Divided Attention: Young children (age 3-4) have considerable difficulties in dividing their attention between two tasks, and often perform at levels equivalent to our closest relative, the chimpanzee, but by age five they have surpassed the chimp (Hermann, Misch, Hernandez-Lloreda & Tomasello, 2015; Hermann & Tomasello, 2015). Despite these improvements, 5-year-olds continue to perform below the level of school-age children, adolescents, and adults. Older children also improve in their ability to shift their attention between tasks or different features of a task (Carlson, Zelazo, & Faja, 2013). A younger child who asked to sort objects into piles based on type of object, car versus animal, or color of object, red versus blue, may have difficulty if you switch from asking them to sort based on type to now having them sort based on color. This requires them to suppress the prior sorting rule. An older child has less difficulty making the switch, meaning there is greater flexibility in their attentional skills. These changes in attention and working memory contribute to children having more strategic approaches to tasks.

Selective Attention: Children’s ability with selective attention tasks improves as they age. However, this ability is also greatly influenced by the child’s temperament (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005), the complexity of the stimulus or task (Porporino, Shore, Iarocci & Burack, 2004), and along with whether the stimuli are visual or auditory (Guy, Rogers & Cornish, 2013). Guy et al. found that children’s ability to selectively attend to visual information outpaced that of auditory stimuli. This may explain why young children are not able to hear the voice of the teacher over the cacophony of sounds in the typical preschool classroom (Jones, Moore & Amitay, 2015). Jones and his colleagues found that 4 to 7-year-olds could not filter out background noise, especially when its frequencies were close in sound to the target sound. In comparison, 8 to 11-year-old older children often performed similarly to adults. Overall, the ability to inhibit irrelevant information improves during this age group, with there being a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence (Vakil, Blachstein, Sheinman, & Greenstein, 2009).

There is a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence. [5]

Sustained Attention: Most measures of sustained attention typically ask children to spend several minutes focusing on one task, while waiting for an infrequent event, while there are multiple distractors for several minutes. Berwid, Curko-Kera, Marks, and Halperin (2005) asked children between the ages of 3 and 7 to push a button whenever a “target” image was displayed, but they had to refrain from pushing the button when a non-target image was shown. The younger the child, the more difficulty he or she had maintaining their attention. [6]

Disorder of Attention: What is Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD)?

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) is a complex, chronic, and heterogenous developmental disorder with typical onset in childhood and known persistence into adulthood. It is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder with a significant impact on the affected individual’s personal, social, academic, and occupational functioning and development. The levels of impairment are brought about by persistent displays of inattention, disorganization, and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. [7]

Inattention

Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 ( or five or more for adolescents and older adults). must be present for at least 6 months and are inappropriate for developmental level:

- .Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

- Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities.

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16, (or five or more for adolescents and older and adults), must be present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

- Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

- Often talks excessively.

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

- Often has trouble waiting for his/her turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years.

- Several symptoms are present in two or more settings, (such as at home, school, or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

Based on the types of symptoms, three kinds (presentations) of AD/HD can occur:

AD/HD Combined Presentation: if enough symptoms of both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past six months.

Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: if enough symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, were present for the past six months: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.[8]

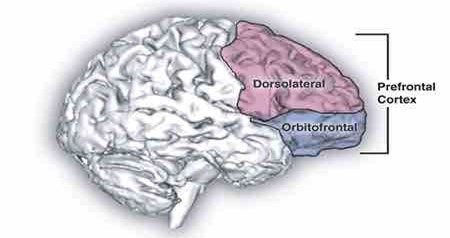

The left prefrontal cortex, shown here in blue, is often affected in ADHD. [9]

Risk Factors

Scientists are studying cause(s) and risk factors in an effort to find better ways to manage and reduce the chances of a person having ADHD. The cause(s) and risk factors for ADHD are unknown, but current research shows that genetics plays an important role. Recent studies link genetic factors with ADHD. [10]

In addition to genetics, scientists are studying other possible causes and risk factors including:

- Brain injury

- Exposure to environmental risks (e.g., lead) during pregnancy or at a young age

- Alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy

- Premature delivery

- Low birth weight

Research does not support the popularly held views that ADHD is caused by eating too much sugar, watching too much television, parenting, or social and environmental factors such as poverty or family chaos. Of course, many things, including these, might make symptoms worse, especially in certain people. But the evidence is not strong enough to conclude that they are the main causes of ADHD. [11]

ADHD and Comorbid Disorders

ADHD often occurs with other disorders. Many children with ADHD have other disorders as well as ADHD, such as behavior or conduct problems, learning disorders, anxiety, and depression. The combination of ADHD with other disorders often presents extra challenges for children, parents, educators, and healthcare providers. Therefore, it is important for healthcare providers to screen every child with ADHD for other disorders and problems.[12]

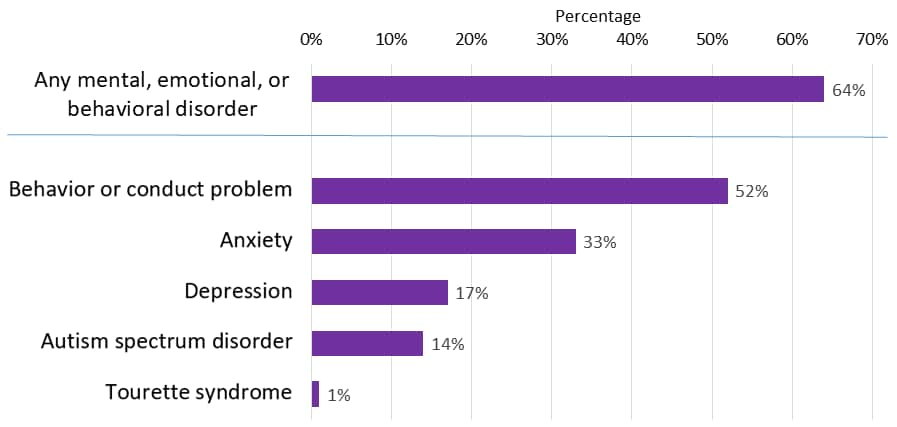

Percent of children with ADHD who had at least one other disorder.[13]

Behavior or Conduct Problems

Children occasionally act angry or defiant around adults or respond aggressively when they are upset. When these behaviors persist over time or are severe, they can become behavior disorders. Children with ADHD are more likely than other children to be diagnosed with a behavioral disorder such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder.

Learning Disorders

Anxiety

Many children have fears and worries. However, when a child experiences so many fears and worries that they interfere with school, home, or play activities, it is an anxiety disorder. Children with ADHD are more likely than those without to develop an anxiety disorder. Examples of anxiety disorders include Separation anxiety – being very afraid when they are away from family, Social anxiety – being very afraid of school and other places where they may meet people and General anxiety – being very worried about the future and about bad things happening to them

Depression

Occasionally being sad or feeling hopeless is a part of every child’s life. When children feel persistent sadness and hopelessness, it can cause problems. Children with ADHD are more likely than children without ADHD to develop childhood depression. Children may be more likely to feel hopeless and sad when they can’t control their ADHD symptoms and the symptoms interfere with doing well at school or getting along with family and friends.

Difficult Peer Relationships

ADHD can make peer relationships or friendships very difficult. Having friends is important to children’s well-being and may be very important to their long-term development. Although some children with ADHD have no trouble getting along with other children, others have difficulty in their relationships with their peers; for example, they might not have close friends, or might even be rejected by other children. Children who have difficulty making friends might also be more likely to have anxiety, behavioral and mood disorders, substance abuse, or delinquency as teenagers.

Risk of Injuries

Children and adolescents with ADHD are likely to get hurt more often and more severely than peers without ADHD. More research is needed to understand why children with ADHD get injured, but it is likely that being inattentive and impulsive puts children at risk. For example, a young child with ADHD may not look for oncoming traffic while riding a bicycle or crossing the street or may do something dangerous without thinking of the possible consequences. Teenagers with ADHD who drive may take unnecessary risks, may forget rules, or may not pay attention to traffic. [14]

Treatment of ADHD

Types of treatment for ADHD include

- Behavior therapy, including training for parents; and

- Medications.

For children with ADHD younger than 6 years of age, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends parent training in behavior management as the first line of treatment, before medication is tried. For children 6 years of age and older, the recommendations include medication and behavior therapy together — parent training in behavior management for children up to age 12 and other types of behavior therapy and training for adolescents. Schools can be part of the treatment as well. AAP recommendations also include adding behavioral classroom intervention and school support. Good treatment plans will include close monitoring of whether and how much the treatment helps the child’s behavior, as well as making changes as needed along the way.

Behavior Therapy

ADHD affects not only a child’s ability to pay attention or sit still at school but also affects relationships with family and other children. Children with ADHD often show behaviors that can be very disruptive to others. Behavior therapy is a treatment option that can help reduce these behaviors; it is often helpful to start behavior therapy as soon as a diagnosis is made. The goals of behavior therapy are to learn or strengthen positive behaviors and eliminate unwanted or problematic behaviors. Behavior therapy for ADHD can include

- Parent training in behavior management;

- Behavior therapy with children; and

- Behavioral interventions in the classroom.

These approaches can also be used together. For children who attend early childhood programs, it is usually most effective if parents and educators work together to help the child.

Medications

Medication can help children manage their ADHD symptoms in their everyday life and can help them control the behaviors that cause difficulties with family, friends, and at school. Several different types of medications are FDA-approved to treat ADHD in children as young as 6 years of age:

- Stimulants are the best-known and most widely used ADHD medications. Between 70-80% of children with ADHD have fewer ADHD symptoms when taking these fast-acting medications.

- Nonstimulants were approved for the treatment of ADHD in 2003. They do not work as quickly as stimulants, but their effect can last up to 24 hours.

Medications can affect children differently and can have side effects such as decreased appetite or sleep problems. One child may respond well to one medication, but not to another. Healthcare providers who prescribe medication may need to try different medications and doses. The AAP recommends that healthcare providers observe and adjust the dose of medication to find the right balance between benefits and side effects. It is important for parents to work with their child’s healthcare providers to find the medication that works best for their child.[15]

Test Yourself

Memory

Test Yourself

Infant Memory

Infant Memory requires a certain degree of brain maturation, so it should not be surprising that infant memory is rather fleeting and fragile. As a result, older children and adults experience infantile amnesia, the inability to recall memories from the first few years of life. Several hypotheses have been proposed for this amnesia. From the biological perspective, it has been suggested that infantile amnesia is due to the immaturity of the infant’s brain, especially those areas that are crucial to the formation of autobiographical memory, such as the hippocampus. From the cognitive perspective, it has been suggested that the lack of linguistic skills of babies and toddlers limit their ability to mentally represent events; thereby, reducing their ability to encode memory. Moreover, even if infants do form such early memories, older children and adults may not be able to access them because they may be employing very different, more linguistically based, retrieval cues than infants used when forming the memory. Finally, social theorists argue that episodic memories of personal experiences may hinge on an understanding of “self”, something that is clearly lacking in infants and young toddlers.

However, in a series of clever studies, Carolyn Rovee-Collier and her colleagues have demonstrated that infants can remember events from their life, even if these memories are short-lived. Three-month-old infants were taught that they could make a mobile, that was hung over their cribs, and move by kicking their legs. The infants were in their cribs, on their backs. A ribbon was tied to one foot and the other end to a mobile. At first, infants made random movements, but then came to realize that by kicking they could make the mobile move. After two 9-minute sessions with the mobile, the mobile was removed. One week later the mobile was reintroduced to one group of infants and most of the babies immediately started kicking their legs, indicating that they remembered their prior experience with the mobile. A second group of infants was shown the mobile two weeks later and the babies only had random movements. The memory had faded (Rovee-Collier, 1987; Giles & Rovee-Collier, 2011). However, when Rovee-Collier and Hayne (1987) found that 3-month-olds could remember the mobile after two weeks if they were shown the mobile and watched it move, even though they were not tied to it. This reminder helped most infants to remember the connection between their kicking and the movement of the mobile. Like many researchers of infant memory, Rovee-Collier (1990) found infant memory to be very context-dependent. In other words, the sessions with the mobile and the later retrieval sessions had to be conducted under very similar circumstances or else the babies would not remember their prior experiences with the mobile. For instance, if the first mobile had had yellow blocks with blue letters, but at the later retrieval session the blocks were blue with yellow letters, the babies would not kick. When the infant was placed on their back, the end of the ribbon was tied to the infant’s leg. Kicking that leg made the mobile move. [16]

When the infant was placed on their back, the end of the ribbon was tied to the infant’s leg. Kicking that leg made the mobile move. [16]

Infants older than 6 months of age can retain information for longer periods of time; they also need less reminding to retrieve information in memory. Studies of Deferred Imitation, that is, the imitation of actions after a time delay, can occur as early as six months of age (Campanella & Rovee-Collier, 2005), but only if infants are allowed to practice the behavior they were shown. By 12 months of age, infants no longer need to practice the behavior in order to retain the memory for four weeks (Klein & Meltzoff, 1999).[17]

Test Yourself

Memory in Early Childhood

Studies of auditory sensory memory have found that the sensory memory trace for the characteristics of a tone last about one second in 2-year-olds, two seconds in 3-year-olds, more than two seconds in 4-year-olds and three to five seconds in 6-year-olds (Glass, Sachse, & vob Suchodoletz, 2008). Other researchers have found that young children hold sounds for a shorter duration than do older children and adults and that this deficit is not due to attentional differences between these age groups but reflect differences in the performance of the sensory memory system (Gomes et al., 1999).

Children in this age group struggle with many aspects of attention, and this greatly diminishes their ability to consciously juggle several pieces of information in memory. The capacity of working memory, that is the amount of information someone can hold in consciousness, is smaller in young children than in older children and adults (Galotti, 2018). The typical adult and teenager can hold a 7-digit number active in their short-term memory. The typical 5-year-old can hold only a 4-digit number active. This means that the more complex a mental task is, the less efficient a younger child will be in paying attention to and actively processing, information in order to complete the task.

As previously discussed, Piaget’s theory has been criticized on many fronts, and updates to reflect more current research have been provided by the Neo-Piagetians, or those theorists who provide “new” interpretations of Piaget’s theory. Morra, Gobbo, Marini and Sheese (2008) reviewed Neo-Piagetian theories, which were first presented in the 1970s, and identified how these “new” theories combined Piagetian concepts with those found in Information Processing. Similar to Piaget’s theory, Neo-Piagetian theories believe in constructivism, assume cognitive development can be separated into different stages with qualitatively different characteristics, and advocate that children’s thinking becomes more complex in advanced stages. Unlike Piaget, Neo-Piagetians believe that aspects of information processing change the complexity of each stage, not logic as determined by Piaget.

Neo-Piagetians propose that working memory capacity is affected by biological maturation, and therefore restricts young children’s ability to acquire complex thinking and reasoning skills. Increases in working memory performance and cognitive skills development coincide with the timing of several neurodevelopmental processes. These include myelination, axonal pruning, synaptic pruning, changes in cerebral metabolism, and changes in brain activity (Morra et al., 2008). Myelination especially occurs in waves between birth and adolescence, and the degree of myelination in particular areas explains the increasing efficiency of certain skills. Therefore, brain maturation, which occurs in spurts, affects how and when cognitive skills develop. Additionally, all Neo-Piagetian theories support that experience and learning interact with biological maturation in shaping cognitive development.[18]

Memory in Middle-to-Late Childhood

During middle and late childhood, children make strides in several areas of cognitive function including the capacity of working memory, their ability to pay attention, and their use of

memory strategies. Both changes in the brain and experience foster these abilities. Differences in memory ability predict both their readiness for school and academic performance in school (PreBler, Krajewski, & Hasselhorn, 2013).

The capacity of working memory expands during middle and late childhood, and research has suggested that both an increase in processing speed and the ability to inhibit irrelevant information from entering memory are contributing to the greater efficiency of working memory during this age (de Ribaupierre, 2002). Changes in myelination and synaptic pruning in the cortex are likely behind the increase in processing speed and ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli (Kail, McBride-Chang, Ferrer, Cho, & Shu, 2013).

Working memory expands during middle and late childhood.[19]

Children with learning disabilities in math and reading often have difficulties with working memory (Alloway, 2009). They may struggle with following the directions of an assignment. When a task calls for multiple steps, children with poor working memory may miss steps because they may lose track of where they are in the task. Adults working with such children may need to communicate: Using more familiar vocabulary, using shorter sentences, repeating task instructions more frequently, and breaking more complex tasks into smaller more manageable steps. Some studies have also shown that more intensive training in working memory strategies, such as chunking, aid in improving the capacity of working memory in children with poor working memory (Alloway, Bibile, & Lau, 2013).

Memory Strategies

Bjorklund (2005) describes a developmental progression in the acquisition and use of memory strategies. Such strategies are often lacking in younger children but increase in frequency as children progress through elementary school. Examples of memory strategies or mnemonics, include rehearsing information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, such “i” before “e” except after “c”, or inventing acronyms, such as “roygbiv” to remember the colors of the rainbow. Schneider, Kron-Sperl, and Hünnerkopf (2009) reported a steady increase in the use of memory strategies from ages six to ten in their longitudinal study. Moreover, by age ten many children were using two or more memory strategies to help them recall information. Schneider and colleagues found that there were considerable individual differences at each age in the use of strategies and that children who utilized more strategies had better memory performance than their same-aged peers. Children may experience deficiencies in their use of memory strategies. A mediation deficiency occurs when a child does not grasp the strategy being taught, and thus, does not benefit from its use. If you do not understand why using an acronym might be helpful, or how to create an acronym, the strategy is not likely to help you. In a production deficiency the child does not spontaneously use a memory strategy and must be prompted to do so. In this case, children know the strategy and are more than capable of using it, but they fail to “produce” the strategy on their own. For example, children might know how to make a list but may fail to do this to help them remember what to bring on a family vacation. A utilization deficiency refers to children using an appropriate strategy, but it fails to aid their performance. Utilization deficiency is common in the early stages of learning a new memory strategy (Schneider & Pressley, 1997; Miller, 2000). Until the use of the strategy becomes automatic it may slow down the learning process, as space is taken up in memory by the strategy itself. Initially, children may get frustrated because their memory performance may seem worse when they try to use the new strategy. Once children become more adept at using the strategy, their memory performance will improve. Sodian and Schneider (1999) found that new memory strategies acquired prior to age eight often show utilization deficiencies with there being a gradual improvement in the child’s use of the strategy. In contrast, strategies acquired after this age often followed an “all-or-nothing” principle in which improvement was not gradual, but abrupt. [47]

Knowledge Base

One’s knowledge base memory has an unlimited capacity and stores information for days, months, or years. It consists of things that we know of or can remember if asked. This is where you want the information to ultimately be stored. The important thing to remember about storage is that it must be done in a meaningful or effective way. In other words, if you simply try to repeat something several times in order to remember it, you may only be able to remember the sound of the word rather than the meaning of the concept. So if you are asked to explain the meaning of the word or to apply a concept in some way, you will be lost. Studying involves organizing information in a meaningful way for later retrieval. Passively reading a text is usually inadequate and should be thought of as the first step in learning material. Writing keywords, thinking of examples to illustrate their meaning, and considering ways that concepts are related are all techniques helpful for organizing information for effective storage and later retrieval.

During middle childhood, children are able to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to and store information. As children enter school and learn more about the world, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. One significant reason is that they continue to have more experiences on which to tie new information. New experiences are similar to old ones or remind the child of something else about which they know. This helps them file away new experiences more easily.

They also have a better understanding of how well they are performing on a task and the level of difficulty of a task. As they become more realistic about their abilities, they can adapt studying strategies to meet those needs. While preschoolers may spend as much time on an unimportant aspect of a problem as they do on the main point, school-aged children start to learn to prioritize and gauge what is significant and what is not. They develop metacognition or the ability to understand the best way to figure out a problem. They gain more tools and strategies (such as “i before e except after c” so they know that “receive” is correct but “recieve” is not.)[20]

As children learn, their knowledge base grows. [21]

Test Yourself

Executive Function

Executive function is an umbrella term for the management, regulation, and control of cognitive processes, including working memory, reasoning, problem-solving, social inhibition, planning, and execution. The executive system is a theoretical cognitive system that manages the processes of executive function. This system is thought to rely on the prefrontal areas of the frontal lobe, but while these areas are necessary for executive function, they are not solely sufficient.

Role of the Executive System

The executive system is thought to be heavily involved in handling novel situations outside the domain of routine, automatic psychological processes (i.e., ones that are handled by learned schemas or set behaviors). There are five types of situations where routine behavior is insufficient for optimal performance, in which the executive system comes into play:

-

-

-

- planning or decision-making;

- error correction or troubleshooting;

- novel situations with unrehearsed reactions;

- dangerous or technically difficult situations;

- overcoming a strong habitual response; resisting temptation.

-

-

A prepotent response is a response for which immediate reinforcement (positive or negative) is available or is associated with that response. Executive functions tend to be invoked when it is necessary to inhibit or override prepotent responses (prepotent response inhibition) that would otherwise occur automatically. For example, on being presented with a potentially rewarding stimulus like a piece of chocolate cake, a person might have the prepotent “automatic” response to take a bite. But if this behavior conflicts with internal plans (such as a diet), the executive system might be engaged to inhibit that response.

Anatomy of the Executive System

Historically, executive functions have been thought to be regulated by the prefrontal regions of the frontal lobes, but this is a matter of ongoing debate. Though prefrontal regions of the brain are necessary for executive function, it seems that non-frontal regions come into play as well. The most likely explanation is that while the frontal lobes participate in all executive functions, other brain regions are necessary. The major frontal structures involved in executive function are:

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: associated with verbal and design fluency, set shifts, planning, response inhibition, working memory, organizational skills, reasoning, problem solving, and abstract thinking.

- Anterior cingulate cortex: inhibition of inappropriate responses, decision making, and motivated behaviors.

- Orbitofrontal cortex: impulse control, maintenance of set, monitoring ongoing behavior, socially appropriate behavior, representing the value of rewards of sensory stimuli.[22]

Development of the Executive System

The abilities of the executive system mature at different rates over time because the brain continues to mature and develop connections well into adulthood. Therefore, a developmental framework is helpful. Executive function corresponds to the development of the growing brain; as the processing capacity of the frontal lobes (and other interconnected regions) increases, the core executive functions emerge. Growth spurts also occur in the development of executive functions; their maturation is not a linear process.

In early childhood, the primary executive functions to emerge are working memory and inhibitory control. Cognitive flexibility, goal-directed behavior, and planning also begin to develop, but are not fully functional. [24]

A child shows higher executive functioning skills when the parents are more warm and responsive, use scaffolding when the child is trying to solve a problem and provide cognitively stimulating environments for the child (Fay-Stammbach, Hawes & Meredith, 2014). For instance, scaffolding was positively correlated with greater cognitive flexibility at age two and inhibitory control at age four (Bibok, Carpendale & Müller, 2009). In Schneider, Kron-Sperl and Hunnerkopf’s (2009) longitudinal study of 102 kindergarten children, the majority of children used no strategy to remember information, a finding that was consistent with previous research. As a result, their memory performance was poor when compared to their abilities as they aged and started to use more effective memory strategies.[25]

During preadolescence, there are major increases in verbal working memory, goal-directed behavior, selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and strategic planning. In adolescence, these functions all become better integrated as they continue developing. [26]

However, self-regulation, or the ability to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self-regulation is especially true when there is high stress or high demand on mental functions (Luciano & Collins, 2012). While high stress or demand may tax even an adult’s self-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent brain may make teens particularly prone to more risky decision-making under these conditions.[27]

Metacognition

Metacognition refers to the knowledge we have about our own thinking and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our own cognitive processes (Bruning, Schraw, Norby, & Ronning, 2004). Generally, metacognitive skills are divided into three component activities. They are: (1) planning: which consists of the anticipation of the sequenced actions to be used to solve the task; (2) monitoring: which implies the review of the actions that are being carried out; and (3) evaluation: which is about comparing the obtained result with the goals established at the beginning of the task. (Flavell, 1992; Veenman et al., 2006; Chatzipanteli et al., 2014).

Metacognitive skills play an important role in a wide variety of activities including the exchange of verbal information, comprehension, reading, writing, attention, memory, problem-solving, learning, or self-control. This helps to understand that metacognitive skills have been identified as a good predictor of academic success, even better than intelligence itself (Bryce et al., 2015; Nelson and Marulis, 2017; Mari and Saka, 2018).

Metacognitive skills emerge very early in life and develop during the following years (Chatzipanteli et al., 2014; Nelson and Marulis, 2017; Roebers, 2017). For example, it has been shown that children of 12 and 18 months, through their behaviors, show that they are already able to reflect on their own decisions to evaluate the accuracy of these and adapt their subsequent behaviors. Thus, they persist more in their behaviors after making a correct decision than when it is incorrect. Therefore, although complex forms of metacognition and verbal expression mature later in childhood, infants in their first year of life, through their behavior, show that they already estimate the accuracy of their simple decisions, monitor their errors, and use these metacognitive evaluations to regulate their subsequent behavior (Goupil and Kouider, 2016). Other studies have also shown that children of 18 months already use spontaneous strategies to correct their mistakes during problem-solving (DeLoache et al., 1985). At 3 years, children are able to monitor their problem-solving behavior, and at 4 years of using metacognitive processing in puzzle tasks (Sperling et al., 2000). Thus, there are various studies that show that, especially from 3 to 5 years of age, children show an important development in their metacognitive skills. Children are capable of solving their problems. They show different ways of planning, monitoring, and evaluating to do so, being able to monitor their behavior through different strategies (comments directed toward themselves, checking behaviors and error detection, behavior repetition to verify the accuracy of the result, use of gestures to support their activity) and establish behavior evaluation (including assessment of performance quality itself and evaluation when the task has been completed) (Whitebread et al., 2009; Bryce and Whitebread, 2012; Whitebread and Basilio, 2012; Whitebread and Pino-Pasternak, 2013). In summary, the behavior of children already during the first year of life and during preschool years reveals basic forms of planning, monitoring, and evaluation (Paulus et al., 2013; Chatzipanteli et al., 2014; Bernard et al., 2015; Roebers, 2017).

However, differences in the execution of metacognitive skills among children can be observed, which indicates the existence of different development rhythms of their metacognitive skills. Some children may not spontaneously acquire competent metacognitive skills. Veenman (2013) pointed out that those children who have metacognitive skills at their disposal but fail to produce them appropriately can be assisted by simple cues and reminders, provided by the context itself (for example, reminder posters) or by the teaching staff. However, children who do not have metacognitive skills may not benefit from simple cues and reminders but they can benefit from further teaching and intervention, given that metacognitive skills are modifiable and teachable even at early ages (Whitebread and Basilio, 2012; Chatzipanteli et al., 2014). [28] Therefore, much of the current study regarding metacognition within the field of cognitive psychology deals with its application within the area of education. Educators strive to increase students’ metacognitive abilities in order to enhance their learning, study habits, goal setting, and self-regulation.

Test Yourself

License: CC BY-SA: Attribution – ShareALike (modified by Marie Parnes)

License: CC BY-SA: Attribution – ShareALike (modified by Marie Parnes)

License: CC BY-SA: Attribution – ShareALike (modified by Marie Parnes)

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Introduction to Psychology - 1st Canadian Edition by Jennifer Walinga and Charles Stangor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Reynolds GD and Romano AC (2016) The Development of Attention Systems and Working Memory in Infancy. Front. Syst. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00015 is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). (modified by Marie Parnes)[33] Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Image by Ady Arif Fauzan from Pixabay ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- I. Cabral, M. D., Liu, S., & Soares, N. (2020). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, risk factors and evaluation in youth. Translational Pediatrics, 9(Suppl 1), S104. https://doi.org/10.21037/tp.2019.09.08 ↵

- Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD by the CDC is in the public domain. ↵

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attention_deficit_hyperactivity_disorder ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html#ref, public domain ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html#ref, public domain ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/conditions.html#ref, public domain ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html#another, public domain ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/conditions.html#ref, public domain ↵

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/treatment.html, public domain ↵

- Image by andreapassaro from Pixabay ↵

- Authored by: Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French. Provided by: College of Lake County Foundation. Locate at: http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes)[47] Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Image by Anchor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA ↵

- Lifespan Development - Module 6: Middle Childhood by Lumen Learning references Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology by Laura Overstreet, licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Image by Ally Laws from Pixabay ↵

- Executive Function and Control Boundless Psychology. Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.comLicense: CC BY-SA: Attribution - ShareALike (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- Executive Function and Control Boundless Psychology. Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com ↵

- Executive Function and Control Boundless Psychology. Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com ↵

- Child Growth and Development: An Open Educational Resources Publication by College of the Canyons by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Richmond is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Executive Function and Control Boundless Psychology. Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com ↵

- Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective 2nd Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 (modified by Marie Parnes) ↵

- https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01298 licensed by CC BY 4.0 ↵

same as multitasking; occurs when mental focus is directed towards multiple ideas, or tasks, at once.

the same as divided attention; occurs when mental focus is directed towards multiple ideas, or tasks, at once.

process that allows one to select and focus on particular input for further processing while simultaneously suppressing irrelevant or distracting information.

a process that enables the maintenance of response persistence and continuous effort over extended periods of time.

a decrease in response to a stimulus after repeated presentations.

any of a range of behavioral disorders occurring primarily in children, including such symptoms as poor concentration, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

a neurobehavioral disorder that is characterized by both hyperactivity (moving constantly including in situations where this is not appropriate, fidgeting, excessive talking, restlessness, “wearing others out”) and impulsivity (making hasty, unplanned actions such as interrupting others).

a neurobehavioral disorder that is characterized primarily by inattentive concentration or a deficit of sustained attention, such as procrastination, hesitation, and forgetfulness.

a neurobehavioral disorder that is characterized primarily by hyperactivity (moving constantly including in situations where this is not appropriate, fidgeting, excessive talking, restlessness) and impulsivity (making hasty, unplanned actions).

the inability to remember events that occurred before the age of three.

the ability to reproduce a previously witnessed action or sequence of actions in the absence of current perceptual support for the action. For example when a child see another child throwing a tantrum and that first child then later throws a tantrum.

believe in constructivism, assume cognitive development can be separated into different stages with qualitatively different characteristics, and advocate that children's thinking becomes more complex in advanced stages.

a theory that posits that humans are meaning makers in their lives and essentially construct their own realities.

the formation and development of a myelin sheath around the axon of a neuron.

the remodeling of axons during neurogenesis

the process by which extra neurons and synaptic connections are eliminated in order to increase the efficiency of neuronal transmissions.

technique used to assist memory, usually by forging a link or association between the new information to be remembered and information previously encoded.

a person's inability to make use of a particular strategy to benefit task performance even if it has been taught to him or her.

failure to find the right or best strategy for completing a task (sometimes even after successful instruction), as opposed to failure in implementing it.

the inability of individuals to improve task performance by using strategies that they have already acquired and demonstrated the ability to use because they are not spurred to do so by memory.

an individual's general background knowledge, which influences his or her performance on most cognitive tasks.

the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully.

a theorized cognitive system in psychology that controls and manages other cognitive processes.

a dominant response, which has been previously reinforced in order to automatize it. For example, if someone is offered a potentially rewarding stimulus like a piece of chocolate cake, a person might have the prepotent "automatic" response to say yes, because the cake is a rewarding stimulus.

ability to overcome previously activated predominant but inappropriate response tendencies, such as saying "no," to a piece of chocolate cake because you are watching your weight or trying to eat healthier.

the period between the approximate ages of 9 and 12.

the ability to understand and manage your behavior and your reactions to feelings and things happening around you

the knowledge and regulation of one's own cognitive processes.