Chapter 4. Consciousness and Sleep

4.4 Sleep Problems and Disorders

Sleep disorders are very common; between 30% and 50% of the United States population suffers from a sleep disorder at some point in their lives (Bixler et al., 1979; Hossain & Shapiro, 2002; Ohayon, 1997, 2002; Ohayon & Roth, 2002). This section will describe several sleep disorders as well as some of their treatment options.

Insomnia

One of the most common sleep disorders is insomnia, which is characterized by difficulty falling or staying asleep. One of the criteria for insomnia involves experiencing these symptoms for at least three nights a week for at least one month (Roth, 2007). People suffering from insomnia often experience increased levels of anxiety about their inability to fall asleep. This can lead to a self-perpetuating cycle where increased anxiety leads to increased arousal, making it even more difficult for them to fall asleep. Chronic insomnia is almost always associated with feeling overtired and may be associated with symptoms of depression.

Multiple factors can contribute to insomnia, including being elderly, drug use, lack of exercise or exercising too close to bedtime, mental health issues, and lack of healthy bedtime routines. As such, insomnia treatment often takes different approaches depending on the cause. Individuals may need to limit their use of stimulant drugs like caffeine or increase their amount of physical exercise during the day. However, relying on over-the-counter (OTC) or prescribed sleep medications should be done with caution as many sleep medications can result in dependence, alter the nature of the sleep cycle, and can even worsen insomnia over time. People with persistent insomnia, particularly if it impacts their quality of life, should seek professional advice.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be highly effective in treating insomnia (Savard et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2013). CBT is a type of psychotherapy that focuses on cognitive processes and problem behaviors. CBT treatment for insomnia may include learning stress management techniques and changing problematic behaviors that could contribute to insomnia, such as spending too much time in bed during the day.

Everyday Connection

Solutions to Support Healthy Sleep

Has something like this ever happened to you? My sophomore college housemate got so stressed out during finals sophomore year he drank almost a whole bottle of Nyquil to try to fall asleep. When he told me, I made him go and see the college therapist. Many college students struggle getting the recommended 7–9 hours of sleep each night. However, for some, it’s not because of all-night partying or late-night study sessions. It’s simply that they feel so overwhelmed and stressed that they cannot fall asleep or stay asleep. One or two nights of sleep difficulty is not unusual, but if you experience anything more than that, you should seek professional advice. Your College Counseling Center can help to advise you.

tips to maintain healthy sleep:

- Stick to the same sleep schedule, even on the weekends. Try going to bed and waking up at the same time every day to keep your biological clock in sync so your body gets in the habit of sleeping every night.

- Avoid stimulating activities for an hour before bed. That includes exercise and bright light from devices, like phones and computers.

- Exercise daily, but not right before bedtime.

- Avoid naps.

- Keep your bedroom temperature between 60 and 67 degrees. People sleep better in cooler temperatures.

- Avoid alcohol, cigarettes, caffeine, and heavy meals before bed. It may feel like alcohol helps you sleep, but it actually disrupts REM sleep and leads to frequent awakenings. Heavy meals may make you sleepy, but they can also lead to frequent awakenings due to gastric distress.

- If you cannot fall asleep, leave your bed and do something else until you feel tired again. Train your body to associate your bed with sleeping rather than other activities like studying, eating, or watching television shows.

Parasomnias

A parasomnia is a type of sleep disorder characterized by unwanted and disruptive motor activity and/or experiences during sleep. These events can occur during either rapid eye movement (REM) or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) phases of sleep. Examples of parasomnias include sleepwalking, restless leg syndrome, and night terrors (Mahowald & Schenck, 2000).

Sleepwalking

In sleepwalking, or somnambulism, the sleeper engages in relatively complex behaviors ranging from wandering about to driving an automobile. During periods of sleepwalking, sleepers often have their eyes open, but they are not responsive to attempts to communicate with them. Sleepwalking typically occurs during slow-wave sleep, but it can occur at any time during a sleep period (Mahowald & Schenck, 2000).

Historically, somnambulism has been treated with a variety of drugs ranging from benzodiazepines to antidepressants. However, the success rate of such treatments is questionable. Guilleminault et al. (2005) found that sleepwalking was not alleviated with the use of benzodiazepines. However, patients who also suffered from sleep-related breathing problems, like sleep apnea, showed a marked decrease in sleep walking when their breathing problems were effectively treated.

Dig Deeper

A Sleepwalking Defense?

On January 16, 1997, Scott Falater sat down to dinner with his wife and children and told them about the difficulties he was experiencing on a project at work. After dinner, he prepared some materials for a church youth group that was scheduled for the following morning, and attempted to repair the family’s swimming pool pump before retiring to bed. The following morning, he awoke to barking dogs and unfamiliar voices from downstairs. As he went to investigate what was going on, he was met by a group of police officers who arrested him for the murder of his wife (Cartwright, 2004; CNN, 1999).

Yarmila Falater’s body was found in the family’s pool with 44 stab wounds. A neighbor called the police after witnessing Falater standing over his wife’s body before dragging her into the pool, and telling his dog to be quiet. He then returned to the house and changed his clothes. Upon a search of the premises, police found blood-stained clothes and a bloody knife in a bag in a Tupperware container hidden in the wheel well of Falater’s car. Falater also had blood stains on his neck.

Remarkably, Falater insisted that he had no recollection of hurting his wife in any way. His children and his wife’s parents all agreed that Falater had an excellent relationship with his wife and they couldn’t think of a reason that would provide any sort of motive to murder her (Cartwright, 2004).

The defense claimed that Scott Falater had killed his wife in his sleep (Cartwright, 2004; CNN, 1999). They argued that he had a history of regular episodes of sleepwalking as a child, and he had even behaved violently toward his sister once when she tried to prevent him from leaving their home in his pajamas during a sleepwalking episode. However, childhood sleep walking is fairly common. Falater had no history of sleep walking as an adult, nor did he have any apparent anatomical brain anomalies or psychological disorders. In Falater’s case, a jury found him guilty of first degree murder in June of 1999 (CNN, 1999). The expert witness for the prosecution pointed out that sleep walking rarely lasts more than 10-20 minutes and the whole series of events took 45 minutes, also they said it would be unusual for the sleep walker not to be awakened by the screams of his victim. There are a number of murder cases where the sleepwalking defense has been offered, but acquittals since 1990 are very rare. In such cases, sleep scientists are now often called upon to produce physiological evidence of a parasomnia (Broughton et al., 1994; Cartwright, 2004; Mahowald, et al., 2005; Pressman, 2007).

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD)

People often have vivid dreams in REM sleep but our brains send messages to our muscles that prevent us acting out our dreams. In REM behavior disorder (RBD) there is a muscle paralysis failure. Consequently, individuals with RBD are often physically very active during REM sleep, especially during disturbing dreams. These behaviors vary widely, but they can include kicking, punching, scratching, yelling, and behaving like an animal that has been frightened or attacked. People with RBD can injure themselves or their sleeping partners when engaging in these behaviors. Furthermore, these types of behaviors ultimately disrupt sleep; affected individuals have no memories that these behaviors have occurred but they are likely to remember the dream associated with the activity (Arnulf, 2012).

RBD is associated with a number of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease. In fact, this relationship is so robust that some view the presence of RBD as a potential aid in the diagnosis of a number of neurodegenerative diseases (Ferini-Strambi, 2011). Clonazepam, an anti-anxiety medication with sedative properties, is most often used to treat RBD. It can be administered alone or in conjunction with melatonin (sleep-inducing hormone secreted by the pineal gland). As part of treatment, the sleeping environment is often modified to make it a safer place for those suffering from RBD (Zangini et al, 2011).

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea occurs when a sleeper periodically stops breathing for 10–20 seconds (or longer) during which time they may briefly waken. People with sleep apnea often feel tired, have frequent headaches, and may experience difficulties staying mentally alert while driving or working (Henry & Rosenthal, 2013). Many individuals first seek treatment because their sleeping partners notice that they snore loudly and/or stop breathing for extended periods of time while sleeping (Henry & Rosenthal, 2013). Sleep apnea is more common in overweight people, and is also linked with smoking and alcohol consumption. Sleep apnea may exacerbate cardiovascular disease (Sánchez-de-la-Torre et al., 2012). While sleep apnea is less common in people who are not overweight, anyone, regardless of their weight, who snores loudly or gasps for air while sleeping, should be checked for sleep apnea.

There are two types of sleep apnea: obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea occurs when an individual’s airway becomes blocked during sleep, and air is prevented from entering the lungs. In central sleep apnea, periods of interrupted breathing are caused by a lack of appropriate signals from the brain (White, 2005).

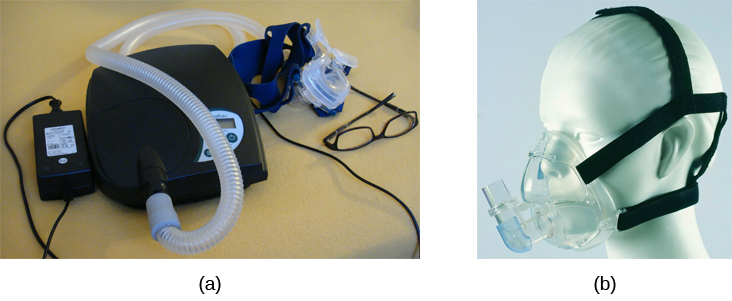

One of the most effective treatments for sleep apnea involves the use of a special device worn during sleep that pumps air into a person’s nose and mouth to keep their airways open (Figure 4.13; McDaid et al., 2009). The continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices usually have a mask that fits over the sleeper’s nose and mouth, however new smaller masks cover only the nose. Many people with sleep apnea dislike wearing the CPAP devices, prompting exploration of alternative treatment options. A newer smaller device, the EPAP (expiratory positive air pressure) device, fits in the nostrils, and has shown promise in double-blind trials as one such alternative (Berry et al., 2011).

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

In sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), an infant stops breathing during sleep and dies. Infants younger than 12 months are at the highest risk for SIDS, and boys are at greater risk than girls. A number of risk factors have been associated with SIDS, including premature birth, maternal smoking during pregnancy, smoking within the home, and hyperthermia (overheating). There may also be differences in both brain structure and function in infants that die from SIDS (Berkowitz, 2012; Mage & Donner, 2006; Thach, 2005).

Decades of research on SIDS has led to a number of recommendations for parents to protect their children (Figure 4.14). Infants should be placed on their backs when put down to sleep, and their cribs should not contain any items which pose suffocation or overheating threats, such as blankets, pillows, or padded crib bumpers (cushions that cover the bars of a crib). Similarly, infants should not wear hats or be overly dressed when sleeping to prevent overheating, and people in the child’s household should abstain from smoking in the home. Recommendations like these have helped to dramatically decrease the number of infant deaths from SIDS (DeLuca et al., 2016; Mitchell, 2009; Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2011).

Narcolepsy

Unlike the other sleep disorders described thus far in this section, a person with narcolepsy cannot stop falling asleep, often at inopportune moments. These sleep episodes are often associated with cataplexy, which is a lack of muscle tone or muscle weakness, and in some cases involves complete paralysis of the voluntary muscles, which may cause the person to collapse. This is similar to the kind of paralysis experienced by healthy individuals during REM sleep (Burgess & Scammell, 2012; Hishikawa & Shimizu, 1995; Luppi et al., 2011). Narcoleptic episodes take on other features of REM sleep. For example, around one third of individuals diagnosed with narcolepsy experience vivid, dream-like hallucinations during narcoleptic attacks (Chokroverty, 2010).

Surprisingly, narcoleptic episodes are often triggered by states of heightened arousal or stress. The typical episode can last from a minute or two to half an hour. Once awakened from a narcoleptic attack, people report that they feel refreshed (Chokroverty, 2010). Frequent narcoleptic episodes often interfere with a person’s ability to perform their job or complete schoolwork, and in some situations can result in significant harm and injury (e.g., driving a car or operating machinery). There is a genetic component to developing narcolepsy, which may be an auto-immune disease. Narcolepsy with cataplexy is associated with reduced secretion of a chemical called orexin from the hypothalamus. Orexin helps to keep us awake (De la Herrán-Arita & Drucker-Colín, 2012; Han, 2012; National Institute of Neurological Diseases, n.d.). Animal models suggest that orexin agonists might be effective treatment for narcolepsy, but research in humans is still lacking (Pizza et al., 2022).Generally, narcolepsy is treated using non-amphetamine psychomotor stimulant drugs, or if they fail, amphetamines are used. More recently, histamine agonists have also shown promise as non-addictive alternatives (National Institute of Neurological Diseases, n.d.).

Other Parasomnias

Restless leg syndrome is another parasomnia that is quite common. People with restless leg syndrome experience discomfort in their legs when trying to fall asleep or if they are inactive. Deliberately moving their legs relieves the discomfort, but makes it difficult to fall or stay asleep. Restless leg syndrome has been associated with a number of other medical diagnoses, such as iron deficiency, pregnancy, chronic kidney disease and diabetes (Mahowald & Schenck, 2000). Treatments for this condition include benzodiazepines, opiates, and anticonvulsants (Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation, n.d.).

Night terrors are episodes of screaming and feelings of intense panic while asleep (Mahowald & Schenck, 2000). Individuals suffering from night terrors often appear to be awake—they might sit up and open their eyes and seem very frightened, however, attempts to console them are ineffective. Night terrors occur during the NREM phase of sleep and people typically have no memory of them on waking (Provini et al., 2011). Night terrors are common among children (40%), but most grow out of them. Generally, night terrors are not treated unless there is some contributing medical or psychological condition (Mayo Clinic, n.d.).