Chapter 8. Higher order cognition: Language and Intelligence

8.6. Development of Intelligence Testing in the United States

Many psychology textbooks suggest that the first intelligence tests were developed in France during the early 20th century. However, the earliest known intelligence tests were actually conducted 3,000 years ago in China, where people wrote essays to determine whether they would be hired as a civil servant. The tests were later expanded to include problem solving questions that bear some similarities to some modern-day intelligence tests (Saklofske et al., 2015). It was not until the 20th century, that intelligence testing came to the Western world. In France in1905, self-trained psychologist, Alfred Binet, and a doctor, Theophile Simon, developed one of the first Western intelligence tests—the Binet-Simon Scale. They hoped that it could be used to identify students who might struggle in school with the aim of providing additional support (Gredler, 2020). Binet conceptualized intelligence as the ability to engage in focused, but flexible thinking, and so the test questions consisted of basic everyday problems designed to evaluate attention, memory, and verbal skills (Guthrie, 1998; National Institutes of Health, 2014). However, Binet warned that this measure could only be considered a test of intelligence if comparisons were made among children from similar backgrounds, because disparities in education or socioeconomic status (SES) would affect the scores (Guthrie, 1998).

Intelligence Testing and the Eugenics Movement

Binet’s warnings were largely ignored. Instead, in the first half of the 20th century, many psychologists, along with huge numbers of other influential people in society, including President Roosevelt, embraced the horrific field of eugenics. The eugenics movement was founded by an English scientist called Francis Galton, who misappropriated Charles Darwin’s work on evolution and Gregor Mendel’s work on heritable traits in plants and animals, by arguing that these ideas could be extended to human traits. Eugenicists believed that genes, not environment, determined intelligence (among other traits), and that people with low intelligence should be prevented from “spreading their genes”. These beliefs were extremely widespread across Europe and the United States (US). Many of the Western psychologists involved in developing intelligence tests were eugenicists, including Spearman in the UK, and Terman in the US. As a result, intelligence testing was weaponized as evidence of low intelligence among people with little formal education. This included women, people of color, and people living in poverty (Guthrie, 1998). Eugenics was used to promote and justify social and economic inequalities in the US, United Kingdom, and the countries that they colonized. The long-term consequences of eugenics-inspired oppressive socioeconomic policies still persist today.

In addition to his eugenicist beliefs, Spearman (1904) also popularized the idea that intelligence could be adequately measured by a single score, which represented a person’s general intelligence (Boake, 2002; Guthrie, 1998). Spearman justified this approach because he had found that people who were proficient in one intellectual domain, e.g., verbal skills, were often equally adept in other domains, such as quantitative reasoning (Biswas-Diener, 2008; Guthrie, 1998). In the 1940s, Raymond Cattell proposed that intelligence consists of two major factors: crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963). Crystallized intelligence is characterized as the ability to retrieve knowledge related to your educational and life experiences. When you learn, remember, and recall information in your classes, you are using crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence on the other hand, encompasses the ability to cope with new situations, see complex relationships, and solve abstract problems (Cattell, 1963). More recent theories suggest that intelligence consists of multiple different domains that go beyond cognitive skills; a person may be strong in one, but not others (Gardner, 1983; Sternberg 1999). The first widely used intelligence test in the US was designed to measure general intelligence, and so minimized the strengths of people who were not good “all-rounders”. The test was developed in 1916 by Lewis Terman, a eugenicist and a professor at Stanford University. Terman adapted the Binet-Simon Scale for use in the US and renamed it the Stanford-Binet scale. Scores on the Stanford-Binet scale were referred to as the intelligence quotient or IQ (Guthrie, 1998). Terman standardized the Stanford-Binet scale using data from 1000 children and 400 adults in the US (Guthrie, 1998), all of whom were White.

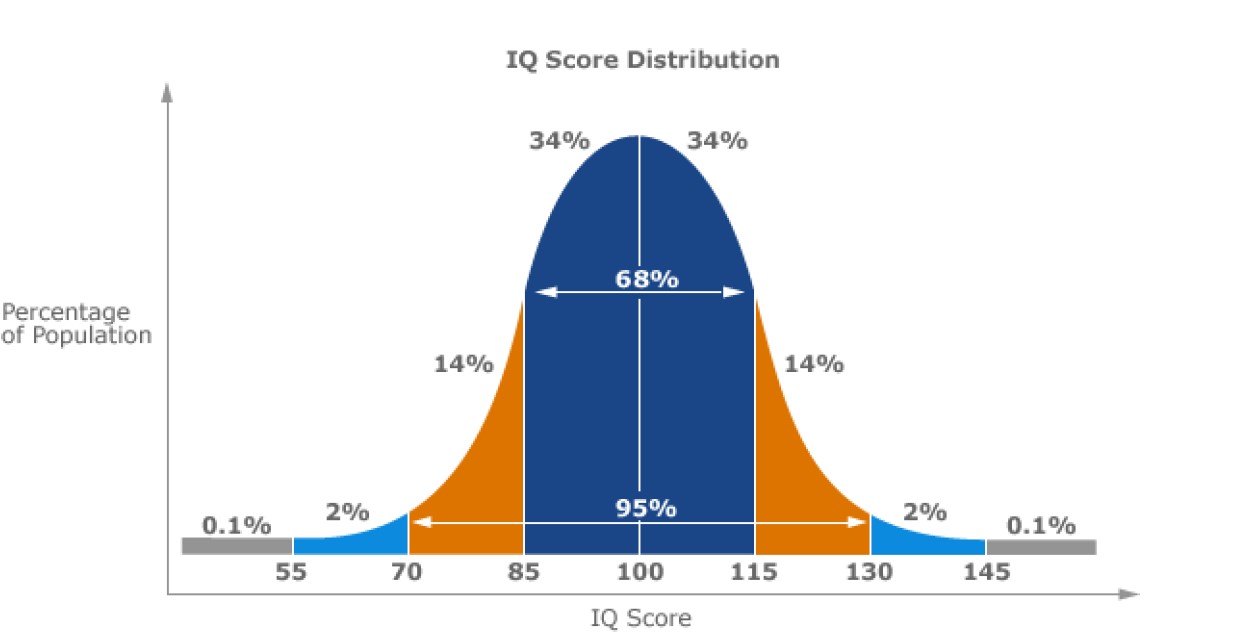

Standardization is a commonly used procedure when developing psychological tests. Raw scores are converted so that they fall in a normal distribution, which is shaped like a “bell curve” (see Figure 8.5), allowing for easy comparisons between individuals (Biswas-Diener, 2018). It is therefore important that the scores are standardized using a large sample of people who are representative of the population. In the Stanford-Binet (and other subsequent IQ tests) the mean IQ score is set at 100. As you can see in Figure 8.6, in the standardized sample, 68% of people have an IQ between 85 and 115; and 96% of people have an IQ of between 70 and 130. There are very few people at the extremes of the scale. You probably have taken at least one standardized aptitude test (like the SAT) in your life. The scores on these tests are standardized in a similar way, but the average score is set around 500 on each SAT subtest.

Excluding people of color from the standardization process was a serious flaw in Terman’s Stanford-Binet intelligence test, as the standardized scores were not representative of the population (Guthrie, 1998). The test relied heavily on verbal skills and asked questions that reflected middle-class values, and so children with little schooling were often misclassified as having low intelligence. The same issues that made the Stanford-Binet test culturally unfair for less educated children also plagued the intelligence tests for adults that were developed for the army during the First World War (Guthrie, 1998).

In 1917, Yerkes (another eugenicist), Terman, and other psychologists from the American Psychological Association helped to design intelligence tests for the US army. These were used to determine work assignments for army recruits (Guthrie, 1998). Not only were the tests culturally biased, but the military psychologists who administered them were all White men, many of whom were blatantly racist, which probably influenced their scoring (Guthrie, 1998). The army then released reports based on the test scores stating that non-Whites, Jews, and Eastern and Southern European immigrants were intellectually inferior to Whites. Moreover, they reported that people with darker skins were less intelligent than light-skinned people (Guthrie, 1998). This misguided report was widely disseminated and was used to further justify and promote many harmful socioeconomic policies. In the US, interracial marriages were banned and racial segregation was strongly enforced to decrease the likelihood of inter-racial relationships developing. Policies such as redlining and racially segregating schools, increased wealth and resources for Whites, and reduced economic opportunities and educational resources for people of color. The 1924 Immigration law severely restricted the admittance of Jews, Eastern and Southern Europeans, and people who were mentally ill, to the United States (Guthrie, 1998).

In keeping with eugenicist ideals, by 1944, 40,000 people had been subjected to forced sterilization in the United States, and 30 states had passed laws legalizing this practice. Forced sterilization targeted mostly poor Black women and immigrants, and included people living in institutions for the mentally ill, people accused of crimes, people with disabilities or chronic illnesses. Scandinavia and Canada also embraced forced sterilization during the same general time period (Kevles, 1999). Adolf Hitler and other German eugenicists were inspired by the widespread ways that the US embraced White supremacy through its sterilization and immigration laws. However, the policies that Germany subsequently created were even more extreme; they mandated killing young children with physical or mental disabilities. Eugenics was also used to justify the persecution and mass murders of six million Jews during the holocaust (Guthrie, 1998). Sterilizations in the United States declined dramatically in the aftermath of the atrocities of the holocaust and in the light of new studies showing that intelligence and mental illness are not solely determined by genes. However, even as laws began to change, the US still carried out about 22,000 more forced sterilizations across 27 states between 1943 and 1963. Some of these sterilizations occurred in some southern and mid-Western states shortly after World War II, when reproductive clinics began “offering” sterilization as a method of birth control to young, mostly Black, poor women in rural areas, and to young native American women. Many of these sterilizations were coerced or done without the woman’s consent (Reilly, 2015). It was not until the 60s and 70s, that US sterilization laws were largely repealed (Sofair & Kaldjian, 2000; Suarez-Balcazar, 2022). However, reproductive injustice continues even today. In 2020, a nurse working for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) made it publicly known that several Latina women were coerced into having unnecessary hysterectomies during their detention by ICE (Suarez-Balcazar, 2022).