Chapter 1. Introduction to Psychology

1.2. Careers and Psychology

Jill Grose-Fifer

Should I major in Psychology?

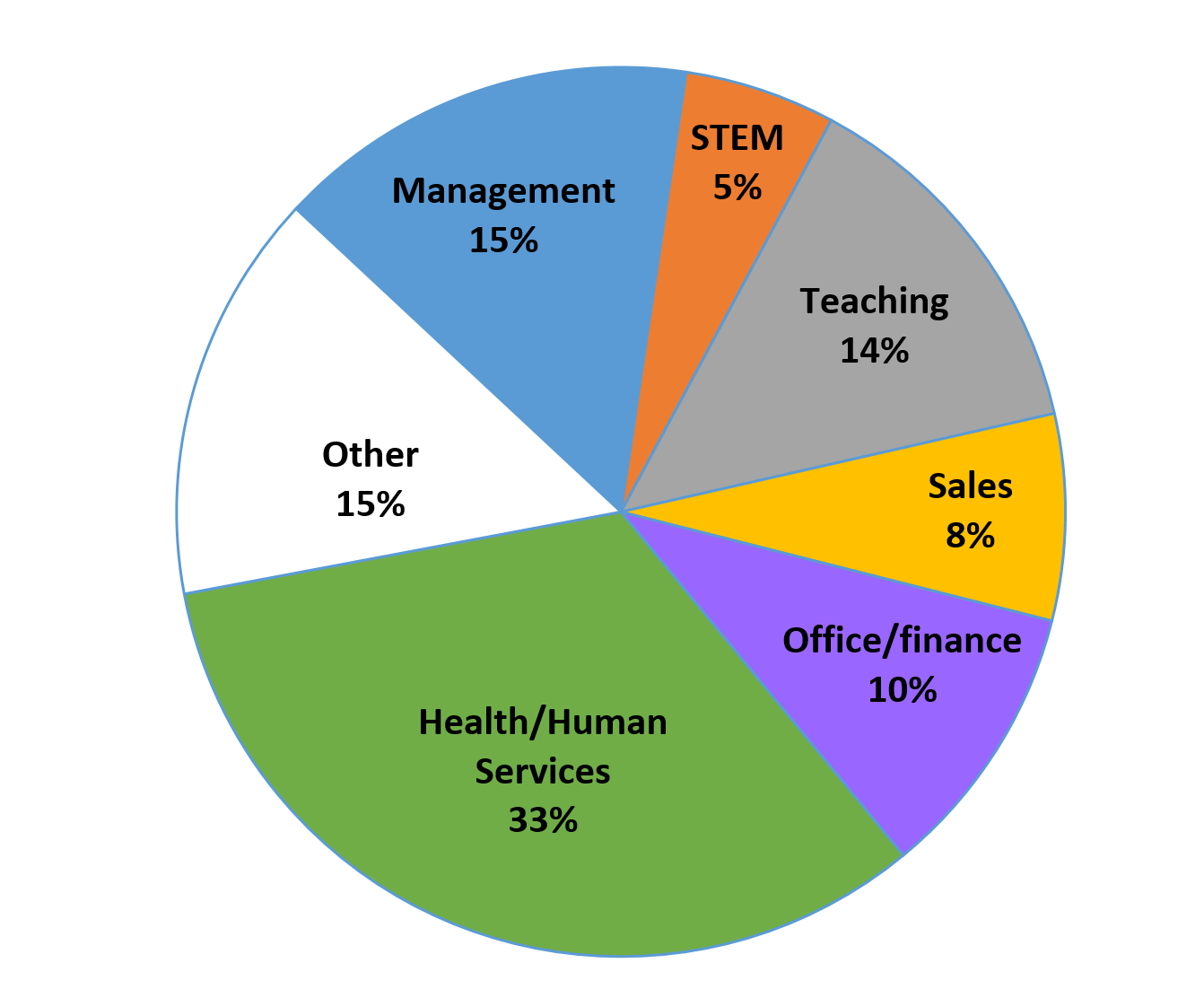

You might be thinking about becoming a Psychology major because you want to pursue a career in psychology. Bear in mind that nearly all undergraduate degrees in the United States are general – they will provide you with a broad education in the liberal arts and hone the skills that you will need for a variety of jobs after you graduate. But, to become a psychologist, you will need a graduate-level degree where you will study the field of psychology in greater depth. Even if you are not planning to go to graduate school, being a psychology major can prepare you for a wide range of jobs. In fact, Psychology is one of the most popular majors for college students (Irwin et al., 2022), so, if you choose this path, you will be in good company! Most psychology majors do NOT go to graduate school (Lin et al., 2017). Figure 1.7 shows you the kind of work they end up doing. As you can see, psychology majors work in a wide variety of jobs after they graduate – but about one-third work in health or human service-related areas. A further 15% work in managerial roles, 14% in teaching, 10% in office/finance work, 8% in sales and 5% in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math fields, often referred to as STEM (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics [NCSES], 2021b).

Courses in the Psychology major help to cultivate the kinds of skills that employers particularly look for in college graduates (Landrum, 2018). Table 1.1 lists the skills that employers value in order of importance (Gray, 2021). Psychology majors learn about the ways that other people (and animals) think, feel, and behave, but they also learn about their own strengths and weaknesses, which can help them to work more effectively with others. Psychology courses help to cultivate good listening and other communication skills, as well as the ability to evaluate and organize information from multiple sources (information literacy). The Psychology major has a strong emphasis on psychology as a science and so students learn about the scientific method and quantitative reasoning – the ability to use math and information to solve real-world problems. Psychology courses encourage students to think critically and analytically, and to learn different ways of collecting, organizing, and analyzing data as well as communicating their findings effectively. Psychology is a “hub science” because it has strong connections to the medical sciences, social sciences, and education; psychology majors sometimes choose to go into these fields after graduation too (Boyack et al., 2005).

| DESIRABLE QUALITIES EMPLOYERS LOOK FOR IN GRADUATES |

|---|

| 1. Problem-solving skills |

| 2. Analytical/quantitative skills |

| 3. Ability to work in a team |

| 4. Communication skills (written) |

| 5. Initiative |

| 6. Strong work ethic |

| 7. Technical skills |

| 8. Flexibility/adaptability |

| 9. Detail-oriented |

| 10. Leadership |

| 11. Communication skills (verbal) |

| 12. Interpersonal skills (relates well to others) |

WATCH THIS VIDEO ABOUT BEING A PSYCHOLOGY MAJOR TO HELP YOU TO DECIDE WHETHER THIS IS THE RIGHT MAJOR FOR YOU (Watch at least until the 10:00 min point – or longer if you are interested).

Your professors and your College Career Advisement Center will be able to help explore your options further, but Table 1.2 below gives you more details about the kinds of jobs that psychology majors go on to do. The Occupational Information Network (O*net ) is a helpful web-based career resource that can help you explore your options further. You can type a job title from the table (or another job you are curious about) into the search bar, you will then see the kinds of duties expected, as well as the skills and qualifications that you will need. For each job, O*net provides information about average salaries within each US state and the likelihood of new jobs being available in the near future.

Many of the positions in Table 1.2 require that you have relevant work experience; you might be able to gain this through internships, fieldwork courses, and doing other types of volunteer work while you are an undergraduate. Your College Career Advisement Center can guide you with your applications for work experience positions. Some employers might provide on-the job training for new employees too. Working with one of your professors on their research projects is a great way to gain research experience, which is especially important if you are thinking of applying to graduate school. Working in a professor’s lab builds research-related skills, but it also allows your professor to get to know you really well. This is important when you ask them to write letters of recommendation for jobs or graduate school. Other ways to get to know your professors well, is to talk to them before and after class and to visit them during their office hours. This can feel awkward at first, but remember that we are here to help you and we love to talk with students.

Table 1.2. Entry Level Jobs for Psychology Majors (after Landrum, 2018)

|

Activities Director |

Labor Relations Manager |

|

Admissions Evaluator |

Loan Officer |

|

Advertising Sales Representative |

Management Analyst |

|

Alumni Director |

Market Research Analyst |

|

Animal Trainer |

Occupational Analyst |

|

Benefits Manager |

Patient Resources Reimbursement Agent |

|

Career/Employment Counselor |

Personnel Recruiter |

|

Career Information Specialist |

Police Officer |

|

Caseworker |

Polygraph Examiner |

|

Child Development Specialist |

Preschool Teacher |

|

Child Welfare/Placement Caseworker |

Probation/Parole Officer |

|

Claims Supervisor |

Project Evaluator |

|

Coach |

Psychiatric Aide/Attendant |

|

Community Organization Worker |

Psychiatric Technician |

|

Community Worker |

Psychological Stress Evaluator |

|

Computer Programmer |

Psychosocial Rehabilitation Specialist (PSR) |

|

Conservation Officer |

Public Relations Representative |

|

Correctional Treatment Specialist |

Purchasing Agent |

|

Corrections Officer |

Real Estate Agent |

|

Criminal Investigator (FBI & other) |

Recreation Leader |

|

Customer Service Representative Supervisor |

Recreation Supervisor |

|

Data Base Administrator |

Research Assistant |

|

Data Base Design Analyst |

Retail Salesperson |

|

Department Manager |

Sales Clerk |

|

Disability Policy Worker |

Social Services Aide |

|

Disability Case Manager |

Substance Abuse Counselor |

|

Employee Health Maintenance Program Specialist |

Systems Analyst |

|

Employee Relations Specialist |

Technical Writer |

|

Employment Counselor |

Veterans Contact Representative |

|

Employment Interviewer |

Veterans Counselor |

|

Financial Aid Counselor |

Victims’ Advocate |

|

Fund Raiser |

Vocational Training Teacher |

|

Health Care Facility Administrator |

Volunteer Coordinator |

|

Information Specialist |

Human Resource Advisor |

|

Job Analyst |

Writer |

Becoming a Psychologist

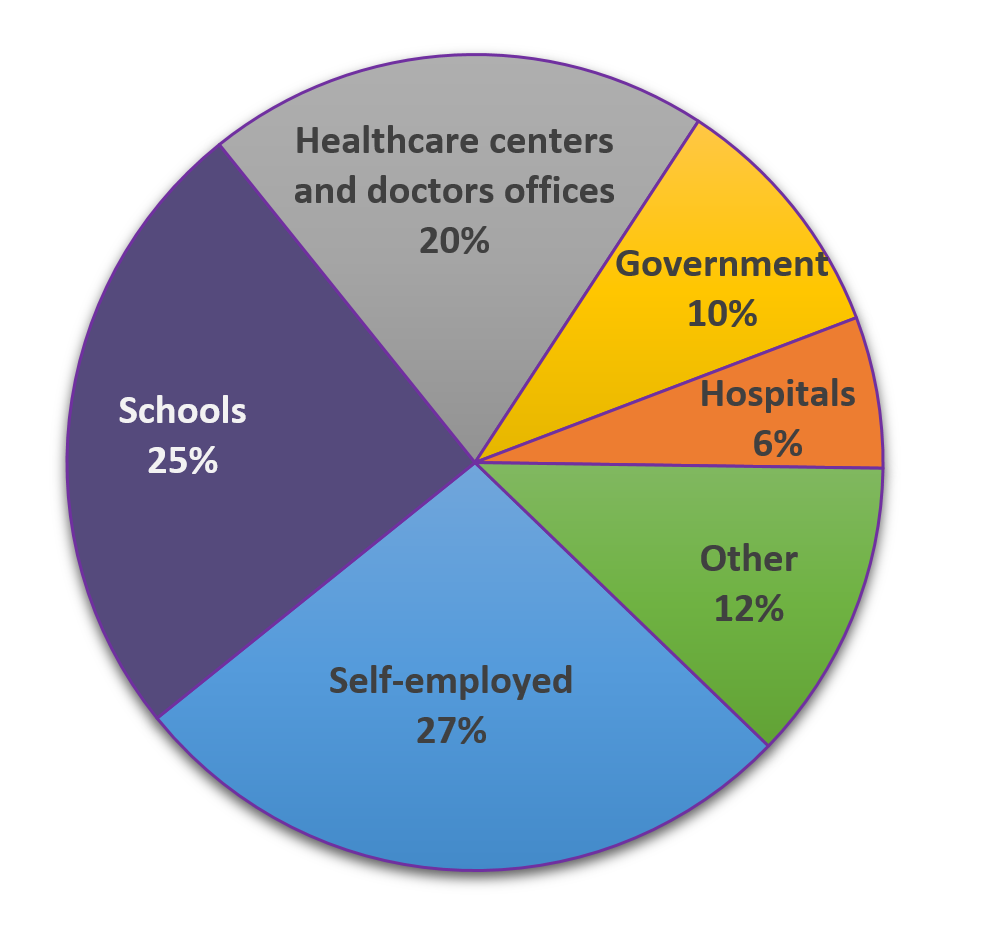

People often assume that all psychologists are mental health providers. This is not true, but health service psychology is a popular career choice for psychologists. In fact, about two thirds of psychologists work as clinical, counseling, or school psychologists (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Nevertheless, health service psychology is only one area of psychology. As you will discover in your Introduction to Psychology course, psychology is a very broad discipline – consisting of numerous different specializations, and many psychologists work outside of health service psychology. Figure 1.11 shows the different settings that psychologists work in. Ask your professor about the kind of graduate degree they earned and the different jobs they have had!

Doctorates in Psychology

To become a psychologist you will need a doctoral degree in psychology. There are three types of doctorate degrees in psychology, the most common of which is a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD). A PhD is a research-based degree where you learn about a specific subfield of psychology in great depth, as well as writing a dissertation based on your own original research. In contrast, Doctor of Psychology (PsyD) degrees are only available in applied fields – such as health service psychology. A much less common doctoral degree in psychology is the Doctorate of Education (EdD), which focuses on both practice and research in areas such as educational psychology and counseling psychology.

Health Service Psychology

Many students want to be health service providers (e.g., a clinical psychologist, counseling psychologist, or school psychologist). If you decide on this kind of career path, you will also need to pass licensing/certification exams that are specific to the State where you will work. It is much easier to become certified/licensed and find a job, if you graduate from a doctoral program that is accredited by the American Psychological Association (APA), or in the case of school psychology—the National Association of School Psychology (NASP).

All doctoral students in health services complete a year-long internship (usually at the end of the program) where they gain intensive hands-on experience in their chosen field. Health service students typically graduate more quickly from PsyD programs than PhD programs because they do not have to carry out extensive research projects (American Psychological Association [APA], 2021a).

How do you decide which doctoral program is best for you?

Deciding on the best program for you will depend in part on the type of work that you want to do. In health service psychology, PsyD students train to become practitioners. Health service PhD students also train to be clinicians, but like other PhD students, they learn how to be teachers and researchers as well. PhDs have more flexibility in terms of the kind of work that they do, they might work in a University or College or other research settings. Health service PhDs might also work in the same clinical or other professional settings that PsyDs work in.

All doctoral programs are long and demanding, and admission is very competitive. In general, PhD programs in psychology accept fewer than 15% of all applicants (click here for the latest statistics for different subfields in psychology. In contrast, PsyD programs accept 40 to 50% of applicants (Norcross & Hogan, 2016). Admissions committees use multiple criteria to evaluate doctoral applicants, including relevant work experience. Students applying to PhD programs typically have worked in a research lab (usually at their college or university), and those applying to health service doctoral programs typically have some clinical or professional experience. Admissions committees also consider grades earned as an undergraduate (known as grade point average [GPA]); application essay(s), letters of recommendation and Graduate Record Entrance (GRE) exam scores (though some programs are phasing out the GRE). Most PhD psychology programs require a GPA of at least a 3.0 on the 4.0 scale, which is the equivalent of a B average. However, the average GPA of students who are actually admitted is much higher at 3.6 (between a B+ and A- average) overall and 3.7 (A- average) in psychology courses (Norcross & Hogan, 2016). Admitted students at very competitive programs often have even higher average GPAs (Wegenek & Buskist, 2010).

As we already mentioned, PsyD programs are somewhat easier to get into than PhD programs, however, there are some disadvantages to consider. PsyD students receive substantially less funding than PhD students; ~1% of PsyD students receive full funding (tuition waiver and a stipend high enough to live on) compared to ~85% of PhD students (Norcross & Hogan, 2016). This means that total student debt after graduation is typically much greater for PsyD compared to PhD students (Norcross & Hogan, 2016; Wilcox et al. 2021). Average student debt is substantially higher for PhDs in health service psychology (~$72,000) compared to other psychology subfields (~$58,000), but it is still considerably less than PsyDs (~$120, 000; Wilcox et al. 2021). Also, it is often more difficult for PsyD graduates to obtain an APA-accredited internship and fewer PsyDs pass the licensing exams on their first try (Norcross & Hogan, 2016). You will find specific information about fees, financial aid, application criteria, and the qualifications of current and recent students on each program’s website.

Other Subfields of Psychology

Although we have talked a lot about health service psychology in this module, as you can see from Table 1.3, people earn doctorates in many other areas of psychology. Slightly more than half of the psychology doctorates awarded in 2018-2020 were in health-service areas, and about one quarter were in general psychology, with the remainder split across multiple other subfields (American Association of Psychology, 2021b). In general, job prospects for psychology doctorates are good. About two-thirds of psychology students accept a job offer (or decide to work for themselves) in the final year of their doctoral program (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), 2021a). Most new doctorates in 2018-2020 went directly into post-doctoral positions, which are paid opportunities for further training and specialization in a field. A further 10% went directly into academic jobs, most likely as assistant professors, and the others were self-employed or worked in industry, business or other settings (NCSES, 2021a).

Table 1.3. Most popular areas of study for psychology doctorates awarded in 2018-20.

Health service psychology fields are shown in yellow.

Data from American Psychological Association (2021b).

|

PSYCHOLOGY SUBFIELD |

PERCENTAGE DOCTORATES AWARDED IN 2018-20 |

|---|---|

|

Clinical Psychology* |

35.9% |

|

Counseling Psychology* |

6.5% |

|

Community Psychology |

0.6% |

|

Developmental Psychology |

0.8% |

|

Educational Psychology |

5.3% |

|

Experimental Psychology |

3.0% |

|

Forensic Psychology |

1.0% |

|

General Psychology |

26.0% |

|

Industrial/Organizational Psychology |

3.1% |

|

School Psychology* |

5.4% |

|

Social Psychology |

0.6% |

|

Other Research Subfields |

7.2% |

|

Other Health Service Psychology Subfields |

4.7% |

To learn more about the kinds of work that different kinds of psychologists do, click on the links below.

Clinical psychologists assess and treat mental, emotional and behavioral problems. NOTE: Psychologists use therapy, not drugs for treatment. Psychiatrists, who have medical degrees, can prescribe drugs for treatment and often work alongside psychologists.

Cognitive psychologists study human perception, thinking, language, and memory.

Community psychologists work with communities to meet people’s needs.

Counseling psychologists use culturally-informed and culturally-sensitive practices to help people prevent and alleviate distress and increase their ability to function better in their lives.

Developmental psychologists study psychological development across the lifespan (although many study a specific period, e.g., infancy, adolescence or old age).

Educational psychologists focus on how effective teaching and learning take place in a variety of settings.

Experimental psychologists are interested in using the scientific method to investigate thinking, feeling, and behavior in humans and non-humans. Many other psychologists also conduct research in this way – learning about research methods (experimental psychology) is an important aspect of most doctoral programs.

Forensic psychologists focus on the intersection between psychology and the law. Some may have clinical training too.

Health psychologists specialize in how biological, psychological, and social factors affect our health.

Industrial/organizational (I/O) psychologists work with businesses and organizations to improve productivity and health of workers and the quality of work life.

Neuroscientists study the relationship between biology (especially the brain) and thinking, feeling, and behavior in humans and/or animals. They might use EEG recording, PET scans, and MRIs to image the nervous system, or they might record the activity from individual nerve cells (neurons).

Neuropsychologists are clinical psychologists who have undergone extensive additional training to learn more about the relationship between the brain and behavior. They often assess and help treat people with brain damage and related disorders. They use behavioral testing in their assessments.

School psychologists help children, adolescents and families to succeed in schools.

Social psychologists study how a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior are affected by interactions with other people.

Sport psychologists use psychological principles to help athletes perform better.

Masters and Specialist Degrees in Psychology

You might be wondering whether it is possible to work in a psychology-related field without a doctorate? The answer is – YES! Increasing numbers of students are graduating with masters or specialized degrees in psychology and related fields, which you can complete in much less time than a doctorate. Table 1.4 shows the most popular areas for masters’ degrees in Psychology. Health service psychology degrees are the most popular (55%). It is easier to get admitted to a masters’ program in psychology than a doctoral program. Like doctoral programs, admissions to Masters’ programs are also typically based on letters of recommendation, your application essay(s), relevant experience, GRE scores (though these are becoming less frequently required) and GPA. Master’s programs often have the same minimum GPA as doctoral programs (3.0), but the GPA of admitted students tends to be a bit lower for Masters compared to doctoral students; 3.4 (overall) and 3.5 in psychology courses (Norcross & Hogan, 2016).

Table 1.4. Most popular areas of study for psychology Masters degrees awarded in 2018-20.

Health service psychology fields are shown in yellow.

Table created from data from American Psychological Association (2021b).

|

PSYCHOLOGY SUBFIELD |

PERCENTAGE MASTERS AWARDED IN 2018-20 |

|

Clinical Psychology* |

8.6 |

|

Counseling Psychology* |

27.9 |

|

Community Psychology |

0.7 |

|

Developmental Psychology |

1.4 |

|

Educational Psychology |

4.4 |

|

Experimental Psychology |

1.0 |

|

Forensic Psychology |

3.2 |

|

General Psychology |

21.0 |

|

Industrial/Organizational Psychology |

5.1 |

|

School Psychology* |

6.7 |

|

Social Psychology |

0.1 |

|

Other Research Subfields |

7.9 |

|

Other Health Service Psychology Subfields |

11.9 |

Let’s take a look at some of the things you can do with a Masters degree in psychology. In many states, you can become an entry-level licensed school psychologist after graduating with a specialized three-year degree from an accredited program (this includes a one-year internship); you will also have to sit licensing exams at the end of this period (National Association of School Psychologists, 2022). Similarly, you can become a licensed/certified counselor after finishing a Master’s degree in a specialized field of counseling (e.g., Addiction Counseling; Career Counseling; Clinical Mental Health; Community Agency Counseling; Forensic Mental Health Counseling; Marriage, Couple and Family Counseling; School Counseling; Student Affairs and College Counseling; Gerontological Counseling; or Counselor Education & Supervision). These programs are typically 2 years, but you will also need to complete an extensive period of post-graduate supervised practical experience (American Counseling Association, 2022) before you can take your professional licensing exams. While you cannot become a licensed clinical psychologist with only a masters’ degree in clinical psychology, you can work as a clinician or a caseworker for mental health agencies under the supervision of a licensed mental health practitioner.

If you are considering becoming a social worker – you will need to complete a Masters in Social Work (MSW), which qualifies you to sit the associated licensing exam (Association of Social Work Boards, 2022). Industrial/organizational (I/O) psychology is currently a rapidly growing field and helps businesses and organizations resolve workplace issues, such as problems with employee engagement, efficiency and retention. Graduates with an Masters in I/O psychology often work in consulting, marketing and human resources, click on this link to see more specific job titles). Other graduates from MA Psychology programs go into similar areas to those shown in Table 1.2, but at a higher level than graduates with a Bachelors degree. They might become research project coordinators or senior research assistants within a lab setting, or might even teach undergraduate courses at a college.

courses designed to build general knowledge and a foundation of logic and reasoning