Reading: The Origins of Civilization

Christopher Brooks

Introduction

What is “civilization”? In English, the word encompasses a wide variety of meanings, often implying a culture possessing some combination of learning, refinement, and political identity. As described in the introductory chapter, it is also a “loaded” term, replete with an implied division between civilization and its opposite, barbarism, with “civilized” people often eager to describe people who are of a different culture as being “uncivilized” in so many words. Fortunately, more practical and value-neutral definitions of the term also exist. Civilization as a historical phenomenon speaks to certain foundational technologies, most significantly agriculture, combined with a high degree of social specialization, technological progress (albeit of a very slow kind in the case of the pre-modern world), and cultural sophistication as expressed in art, learning, and spirituality.

In turn, the study of civilization has been the traditional focus of history, as an academic discipline, since the late nineteenth century. As academic fields became specialized over the course of the 1800s CE, history identified itself as the study of the past based on written artifacts. A sister field, archeology, developed as the study of the past based on non-written artifacts (such as the remains of bodies in grave sites, surviving buildings, and tools). Thus, for practical reasons, the subject of “history” as a field of study begins with the invention of writing, something that began with the earliest civilization itself, that of the Fertile Crescent (described below). That being noted, history and archeology remain closely intertwined, especially since so few written records remain from the remote past that most historians of the ancient world also perform archeological research, and all archeologists are also at least conversant with the relevant histories of their areas of study.

Hominids

Human beings are members of a species of hominid, which is the same biological classification that includes the advanced apes like chimpanzees. The earliest hominid ancestor of humankind was called Australopithecus: a biological species of African hominid (note: hominid is the biological “family” that encompasses great apes – Australopithecus, as well as Homo Sapiens, are examples of biological “species” within that family) that evolved about 3.9 million years ago. Australopithecus was similar to present-day chimpanzees, loping across the ground on all fours rather than standing upright, with brains about one-third the size of the modern human brain. They were the first to develop tool-making technology, chipping obsidian (volcanic glass) to make knives. From Australopithecus, various other hominid species evolved, building on the genetic advantages of having a large brain and being able to craft simple tools.

Homo sapiens emerged in a form biologically identical to present-day humankind by about 300,000 years ago (fossil evidence frequently revises that number – the oldest known specimen was discovered in Morocco in 2017). Armed with their unparalleled craniums, Homo sapiens created sophisticated bone and stone implements, including weapons and tools, and also mastered the use of fire. They were thus able to hunt and protect themselves from animals that had far better natural weapons, and (through cooking) eat meat that would have been indigestible raw. Likewise, animal skins served as clothes and shelter, allowing them to exist in climates that they could not have settled otherwise.

Civilization and Agriculture

Thus, human beings have existed all over the world for many thousands of years. Human civilization, however, has not. The word civilization is tied to the Greek word for city, along with words like “civil” and “civic.” The key element of the definition is the idea that a large number of people come together in a group that is too large to consist only of an extended family group. Once that occurred other discoveries and developments, from writing to mathematics to organized religion, followed.

Up until that point in history, however, cities had not been possible because there was never enough food to sustain a large group that stayed in a single place for long. Ancient humans were hunter-gatherers. They followed herds of animals on the hunt and they gathered edible plants as well. This way of life fundamentally worked for hundreds of thousands of years – it was the basis of life for the very people who populated the world as described above. The problem with the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, however, is that it is extremely precarious: there is never a significant surplus of caloric energy, that is, of food, and thus population levels among hunting-gathering people were generally static. There just was not enough food to sustain significant population growth.

Starting around 9,500 BCE, humans in a handful of regions around the world discovered agriculture, that is, the deliberate cultivation of edible plants. People discovered that certain seeds could be planted and crops could be reliably grown. Sometimes after that, people in the same regions began to domesticate animals, keeping herds of cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats in controlled conditions, defending them from predators, and eating them and using their hides. It is impossible to overstate how important these changes were. Even fairly primitive agriculture can produce fifty times more caloric energy than hunting and gathering does. The very basis of human life is how much energy we can derive from food; with agriculture and animal domestication, it was possible for families to grow much larger and overall population levels to rise dramatically.

One of the noteworthy aspects of this transition is that hunting-gathering people actually had much more leisure time than farmers did (and were also healthier and longer-lived). Archaeologists and anthropologists have determined that hunter-gatherer people generally only “worked” for a few hours a day, and spent the rest of their time in leisure activities. Meanwhile, farmers have always worked incredibly hard for very long hours; in many places in the ancient world, there were groups of people who remained hunter-gatherers despite knowing about agriculture, and it is quite possible they did that because they saw no particular advantage in adopting agriculture. There were also many areas that practiced both – right up until the modern era, many farmers also foraged in areas of semi-wilderness near their farms.

Agriculture was developed in a few different places completely independently. According to archeological evidence, agriculture did not start in one place and then spread; it started in a few distinct areas and then spread from those areas, sometimes meeting in the middle. For example, agriculture developed independently in China by 5000 BCE, and of course agriculture in the Americas (starting in western South America) had nothing to do with its earlier invention in the Fertile Crescent.

The most important regions for the development of Western Civilization were Mesopotamia and Egypt, because it was from those regions that the different technologies, empires, and ideas that came together in Western Civilization were forged. Thus, it is important to emphasize that the original heartland of Western Civilization was not in Greece or anywhere else in Europe; it was in the Middle East and North Africa. Many of the different elements of Western Civilization, things like scientific inquiry, the religions of the book (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), engineering, and mathematics, were originally conceived in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The earliest sites of agriculture emerged in the Fertile Crescent, the region encompassing Egypt along the Nile river, the Near East, and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia, on the eastern end of the Fertile Crescent, was the cradle of Western Civilization. It has the distinction of being the very first place on earth in which the development of agriculture led to the emergence of the essential technologies of civilization. Many of the great scientific advances to follow, including mathematics, astronomy, and engineering, along with political networks and forms of organization like kingdoms, empires, and bureaucracy all originated in Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia is a region in present-day Iraq. The word Mesopotamia is Greek, meaning “between the rivers,” and it refers to the area between the Tigris and Euphrates, two of the most important waterways in the ancient world. It is no coincidence that it was here that civilization was born: like nearby Egypt and the Nile river, early agriculture relied on a regular supply of water in a highly fertile region. The ancient Mesopotamians had everything they needed for agriculture, they just had to figure out how to cultivate cereals and grains (natural varieties of which naturally occurred in the area, as noted in the last chapter) and how to manage the sudden floods of both rivers.

Mesopotamia’s climate was much more temperate and fertile than it is today. There is a great deal of evidence (e.g. in ancient art, in archeological discoveries of ancient settlements, etc.) that Mesopotamia was once a grassland that could support both large herds of animals and abundant crops. Thus, between the water provided by the rivers and their tributaries, the temperate climate, and the prevalence of the plant and animal species in the area that were candidates for domestication, Mesopotamia was better suited to agriculture than practically any other region on the planet.

While the Tigris and Euphrates provided abundant water, they were highly unpredictable and given to periodic flooding. The southern region of Mesopotamia, Sumer, has an elevation decline of only 50 meters over about 500 kilometers of distance, meaning the riverbeds of both rivers would have shifted and spread out over the plains in the annual floods. Over time, the inhabitants of villages realized that they needed to work together to build larger-scale levees, canals, and dikes to protect against the floods. One theory regarding the origins of large-scale settlements is that, when enough villages got together to work on these hydrological systems, they needed some kind of leadership to direct the efforts, leading to systems of governance and administration. Thus, the earliest cities in the world may have been born not just out of agriculture, but out of the need to manage the natural resource of water.

The first settlements that straddled the line between “towns” and real “cities” existed around 4000 BCE, but a truly urban society in Mesopotamia was in place closer 3000 BCE, wherein a few dozen city-states managed the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates. A note on the chronology: the town of Çatal Höyük discussed above existed over four thousand years before the first great cities in Mesopotamia. It is important to bear this in mind, because when considering ancient history (in this case, in a short chapter of a textbook), it can seem like it all happened quite rapidly, that people discovered agriculture and soon they were building massive cities and developing advanced technology. That simply was not the case: compared to the hundreds of thousands of years preceding the discovery of agriculture, things moved “quickly,” but from a modern perspective, it took a very long time for things to change.

One compelling theory about the period between the invention of agriculture and the emergence of large cities (again, between about 8,000 BCE and 4000 BCE) is that a hybrid lifestyle of farming and gathering appears to have been very common in the large wetlands along the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris. Given the richness of dietary options in the region at the time, people lived in small communities for millenia without feeling compelled to build larger settlements. Somehow, however, a regime eventually emerged that imposed a new form of social organization and hierarchy, introducing taxation, large-scale building projects, and unfree labor (i.e. both slavery and forms of indentured labor). In turn, this appears to have occurred in the areas that grew cereal grains like wheat and barley extensively, because cereal grains were easy to collect and store, making them easy to tax.

The result of these new hierarchies were the first true cities emerged in the southern region of Sumer. There, the two rivers join in a large delta that flows into the Persian Gulf. Farther up the rivers, the northern region of Mesopotamia was known as Akkad. The division is both geographical and lingual: ancient Sumerian is not related to any modern language, but the Akkadian family of languages was Semitic, related to modern languages like Arabic and Hebrew. Urban civilization eventually flourished in both regions, starting in Sumer but quickly spreading north.

One early Sumerian city was Uruk, which was a large city by 3500 BCE. Uruk had about 50,000 people in the city itself and the surrounding region. It was a major center for long-distance trade, with its trade networks stretching all across the Middle East and as far east as the Indus river valley of India, with merchants relying on caravans of donkeys and the use of wheeled carts. Trade linked Mesopotamia and Anatolia (the region of present-day Turkey) as well. The economy of Uruk was what historians call “redistributive,” in which a central authority has the right to control all economic activity, essentially taxing all of it, and then re-distributing it as that authority sees fit. Practically speaking, this entailed the collection of foodstuffs and wealth by each city-state’s government, which then used it to “pay” (sometimes in daily allotments of food and beer) workers tasked with constructing walls, roads, temples, and palaces.

The influence of Sumerian civilization was felt all over the Mesopotamian region. The above map depicts the “Urukean expansion,” a period in the fourth millennium BCE in which Sumerian material culture (and presumably Sumerian people) spread hundreds of miles from Sumer itself.

Political leaders in ancient Mesopotamia appear to have been drawn from both priesthoods and the warrior elite, with the two classes working closely together in governing the cities. Each Mesopotamian city was believed to be “owned” by a patron god, a deity that watched over it and would respond to prayers if they were properly made and accompanied by rituals and sacrifices. The priests of Uruk predicted the future and explained the present in terms of the will of the gods, and they claimed to be able to influence the gods through their rituals. They claimed all of the economic output of Uruk and its trade network because the city’s patron god “owned” the city, which justified the priesthood’s control. They did not only tax the wealth, the crops, and the goods of the subjects of Uruk, but they also had a right to demand labor, requiring the common people (i.e. almost everyone) to work on the irrigation systems, the temples, and the other major public buildings.

Meanwhile, the first kings were almost certainly war leaders who led their city-states against rival city-states and against foreign invaders. They soon ascended to positions of political power in their cities, working with the priesthood to maintain control over the common people. The Mesopotamian priesthood endorsed the idea that the gods had chosen the kings to rule, a belief that quickly bled over into the idea that the kings were at least in part divine themselves. Kings had superseded priests as the rulers by about 3000 BCE, although in all cases kings were closely linked to the power of the priesthood. In fact, one of the earliest terms for “king” was ensis, meaning the representative of the god who “really” ruled the city. Thus, the typical early Mesopotamian city-state, right around 2500 BCE, was of a city-state engaged in long-distance trade, ruled by a king who worked closely with the city’s priesthood and who frequently made war against his neighbors.

Belief, Thought and Learning

The Mesopotamians believed that the gods were generally cruel, capricious, and easily offended. Humans had been created by the gods not to enjoy life, but to toil, and the gods would inflict pain and suffering on humans whenever they (the gods) were offended. A major element of the power of the priesthood in the Mesopotamian cities was the fact that the priests claimed to be able to soothe and assuage the gods, to prevent the gods from sending yet another devastating flood, epidemic, or plague of locusts. It is not too far off to say that the most important duty of Mesopotamian priests was to beg the gods for mercy.

All of the Mesopotamian cities worshiped the same gods, referred to as the Mesopotamian pantheon (pantheon means “group of gods.”) As noted above, each city had its own specific patron deity who “owned” and took particular interest in the affairs of that city. In the center of each city was a huge temple called a ziggurat, or step-pyramid, a few of which still survive today. Unlike the Egyptian pyramids that came later, Mesopotamian ziggurats were not tombs, but temples, and as such they were the centerpieces of the great cities. They were not just the centers of worship, but were also banks and workshops, with the priests overseeing the exchange of wealth and the production of crafts.

Alongside the development of religious belief, science made major strides in Mesopotamian civilization. The Mesopotamians were the first great astronomers, accurately mapping the movement of the stars and recording them in star charts. They invented functional wagons and chariots and, as seen in the case of both ziggurats and irrigation systems, they were excellent engineers. They also invented the 360 degrees used to measure angles in geometry and they were the first to divide a system of timekeeping that used a 60-second minute. Finally, they developed a complex and accurate system of arithmetic that would go on to form the basis of mathematics as it was used and understood throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

At the same time, however, the Mesopotamians employed “magical” practices. The priests did not just conduct sacrifices to the gods, they practiced the art of divination: the practice of trying to predict the future. To them, magic and science were all aspects of the same pursuit, namely trying to learn about how the universe functioned so that human beings could influence it more effectively. From the perspective of the ancient Mesopotamians, there was little that distinguished religious and magical practices from “real” science in the modern sense. Their goals were the same, and the Mesopotamians actively experimented to develop both systems in tandem.

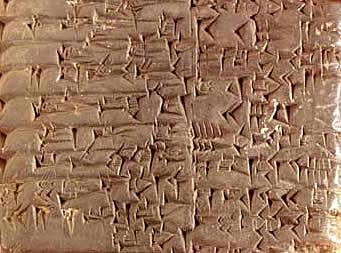

The Mesopotamians also invented the first systems of writing, first developed in order to keep track of tax records sometime around 3000 BCE. Their style of writing is called cuneiform; it started out as a pictographic system in which each word or idea was represented by a symbol, but it eventually changed to include both pictographs and syllabic symbols (i.e. symbols that represent a sound instead of a word). While it was originally used just for record-keeping, writing soon evolved into the creation of true forms of literature.

An example of cuneiform script, carved into a stone tablet, dating from c. 2400 BCE.

The first known author in history whose name and some of whose works survive was a Sumerian high priestess, Enheduanna. Daughter of the great conqueror Sargon of Akkad (described below), Enheduanna served as the high priestess of the goddess Innana and the god of the moon, Nanna, in the city of Ur after its conquest by Sargon’s forces. Enheduanna wrote a series of hymns to the gods that established her as the earliest poet in recorded history, praising Innana and, at one point, asking for the aid of the gods during a period of political turmoil.

Enheduanna did not record the first known work of prose, however, whose author or authors remain unknown. Remembered as The Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest surviving work of literature, it is the best known of the surviving Mesopotamian stories. The Epic describes the adventures of a partly-divine king of the city of Uruk, Gilgamesh, who is joined by his friend Enkidu as they fight monsters, build great works, and celebrate their own power and greatness. Enkidu is punished by the gods for their arrogance and he dies. Gilgamesh, grief-stricken, goes in search of immortality when he realizes that he, too, will someday die. In the end, immortality is taken from him by a serpent, and humbled, he returns to Uruk a wiser, better king.

Like Enheduanna’s hymns, which reveal at times her own personality and concerns, The Epic of Gilgamesh is a fascinating story in that it speaks to a very sophisticated and recognizable set of issues: the qualities that make a good leader, human failings and frailty, the power and importance of friendship, and the unfairness of fate. Likewise, a central focus of the epic is Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality when he confronts the absurdity of death. Death’s seeming unfairness is a distinctly philosophical concern that demonstrates an advanced engagement with human nature and the human condition present in Mesopotamian society.

Along with literature, the other great written accomplishments of the Mesopotamians were their systems of law. The most substantial surviving law code is that of the Babylonian king Hammurabi, dating from about 1780 BCE. Hammurabi’s law code went into great detail about the rights and obligations of Babylonians. It drew legal distinctions between the “free men” or aristocratic citizens, commoners, and slaves, treating the same crimes very differently. The laws speak to a deep concern with fairness – the code tried to protect people from unfair terms on loans, it provided redress for damaged property, it even held city officials responsible for catching criminals. It also included legal protections for women in various ways. While women were unquestionably secondary to men in their legal status, the Code still afforded them more rights and protections than did many codes of law that emerged thousands of years later.

War and Empire

Mesopotamia represents the earliest indications of large-scale warfare. Mesopotamian cities always had walls – some of which were 30 feet high and 60 feet wide, essentially enormous piles of earth strengthened by brick. The evidence (based on pictures and inscriptions) suggests, however, that most soldiers were peasant conscripts with little or no armor and light weapons. In these circumstances, defense almost always won out over offense, making the actual conquest of foreign cities very difficult if not impossible, and hence while cities were around for thousands of years (again, from about 3500 BCE), there were no empires yet. Cities warred on one another for territory, captives, and riches, but they rarely succeeded in conquering other cities outright. War was instead primarily about territorial raids and perhaps noble combats meant to demonstrate strength and power.

Over the course of the third millennium BCE, chariots became increasingly important in warfare. Early chariots were four-wheeled carts that were clumsy and hard to maneuver. They were still very effective against hapless peasants with spears, however, so it appears that when rival Mesopotamian city-states fought actual battles, they consisted largely of massed groups of chariots carrying archers who shot at each other. Noble charioteers and archers could win glory for their skill, even though these battles were probably not very lethal (compared to later forms of war, at any rate).

The first time that a single military leader managed to conquer and unite many of the Mesopotamian cities was in about 2340 BCE, when the king Sargon the Great, also known as Sargon of Akkad (father of Enheduanna, described above), conquered almost all of the major Mesopotamian cities and forged the world’s first true empire, in the process uniting the regions of Akkad and Sumer. His empire appears to have held together for about another century, until somewhere around 2200 BCE. Sargon also created the world’s first standing army, a group of soldiers employed by the state who did not have other jobs or duties. One inscription claims that “5,400 soldiers ate daily in his palace,” and there are pictures not only of soldiers, but of siege weapons and mining (digging under the walls of enemy fortifications to cause them to collapse).

The expansion of Sargon’s empire, which eventually stretched from present-day Lebanon to Sumer.

Sargon himself was born an illegitimate child and was, at one point, a royal gardener who worked his way up in the palace, eventually seizing power in a coup. He boasted about his lowly origins and claimed to protect and represent the interests of common people and merchants. Sargon appointed governors in his conquered cities, and his whole empire was designed to extract wealth from all of its cities and farmlands and pump it back to the capital of Akkad, which he built somewhere near present-day Baghdad. While his descendents did their best to hold on to power, the resentment of the subject cities eventually resulted in the empire’s collapse.

The next major Mesopotamian empire was the “Ur III” dynasty, named after the city-state of Ur which served as its capital and founded in about 2112 BCE. Just as Sargon had, the king Ur-Nammu conquered and united most of the city-states of Mesopotamia. The most important historical legacy of the Ur III dynasty was its complex system of bureaucracy, which was more effective in governing the conquered cities than Sargon’s rule had been.

Bureaucracy (which literally means “rule by office”) is one of the most underappreciated phenomena in history, probably because the concept is not particularly exciting to most people. The fact remains that there is no more efficient way yet invented to manage large groups of people: it was viable to coordinate small groups through the personal control and influence of a few individuals, but as cities grew and empires formed, it became untenable to have everything boil down to personal relationships. An efficient bureaucracy, one in which the individual people who were part of it were less important than the system itself (i.e. its rules, its records, and its chain of command), was always essential in large political units.

The Ur III dynasty is an example of an early bureaucratic empire. Historians have more records of this dynasty than any other from this period of ancient Mesopotamia thanks to its focus on codifying its regulations. The kings of Ur III were very adept at playing off their civic and military leaders against each other, appointing generals to direct troops in other cities and making sure that each governor’s power relied on his loyalty to the king. The administration of the Ur III dynasty divided the empire into three distinct tax regions, and its tax bureaucracy collected wealth without alienating the conquered peoples as much as Sargon and his descendants had (despite its relative success, Ur III, too, eventually collapsed, although it was due to a foreign invasion rather than an internal revolt).

Finally, there was the great empire of Hammurabi (which lasted from 1792 – 1595 BCE), the author of the code of laws noted above. By about 1780 BCE, Hammurabi conquered many of the city-states near Babylon in the heart of Mesopotamia. He was not only concerned with laws, but also with ensuring the economic prosperity of his empire; while it is impossible to know how sincere he was about it, he wanted to be remembered as a kind of benevolent dictator who looked after his subjects. The Babylonian empire re-centered Mesopotamia as a whole on Babylon. It lasted until 1595 BCE when it was defeated by an empire from Anatolia known as the Hittites.

What all of these ancient empires had in common beyond a common culture was that they were very precarious. Their bureaucracies were not large enough or organized enough to manage large populations easily, and rebellions were frequent. There was also the constant threat of what the surviving texts refer to as “bandits,” which in this context means the same thing as “barbarians.” To the north of Mesopotamia is the beginning of the great steppes of Central Asia, the source of limitless and almost nonstop invasions throughout ancient history. Nomads from the steppe regions were the first to domesticate horses, and for thousands of years only steppe peoples knew how to fight directly from horseback instead of using chariots. Thus, the rulers of the Mesopotamian city-states and empires all had to contend with policing their borders against a foe they could not pursue, while still maintaining control over their own cities.

This precarity was responsible for the fact that these early empires were not especially long-lasting, and were unable to conquer territory outside of Mesopotamia itself. What came afterwards were the first early empires that, through a combination of governing techniques, beliefs, and technology, were able to grow much larger and more powerful.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Fertile crescent map – NormanEinstein

Sumerian expansion map – Sémhur

Cuneiform – Salvor

Sargon map – Nareklm

Chapter attribution: This chapter has been derived with minor modifications from Chapter 1: The Origins of Civilizations in Western Civilization: A Concise History.