Reading: Early Medieval Europe

Christopher Brooks

Introduction

Once the last remnants of Roman power west of the Balkans were extinguished in the late fifth century CE, the history of Europe moved into the period that is still referred to as “medieval,” meaning “middle” (between). Roughly 1,000 years separated the fall of Rome and the beginning of the Renaissance, the period of “rebirth” in which certain Europeans believed they were recapturing the lost glory of the classical world. Historians have long since dismissed the conceit that the Middle Ages were nothing more than the “Dark Ages” so maligned by Renaissance thinkers, and thus this chapter seeks to examine the early medieval world on its own terms – in particular, what were the political, social, and cultural realities of post-Roman Europe?

The Latin Church

After the fall of the western Roman empire, it was the Church that united Western Europe and provided a sense of European identity. That religious tradition would persist and spread, ultimately extinguishing the so-called “pagan” religions, despite the political fragmentation left in the wake of the fall of Rome. The one thing that nearly all Europeans eventually came to share was membership in the Latin Church (a note on nomenclature: for the sake of clarity, this chapter will use the term “Latin” instead of “Catholic” to describe the western Church based in Rome during this period, because both the western and eastern “Orthodox” churches claimed to be equally “catholic”: universal). As an institution, it alone was capable of preserving at least some of the legacy of ancient Rome.

That legacy was reflected in the learning preserved by the Church. For example, even though Latin faded away as a spoken language, all but vanishing by about the eighth century even in Italy, the Bible and written communication between educated elites was still in Latin. Latin went from being the vernacular of the Roman Empire to being, instead, the language of the educated elite all across Europe. An educated person (almost always a member of the Church in this period) from England could still correspond to an educated person in Spain or Italy, but that correspondence would take place in Latin. He or she would not be able to speak to their counterpart on the other side of the subcontinent, but they would share a written tongue.

Christianity displayed a remarkable power to convert even peoples who had previously proved militarily stronger than Christian opponents, from the Germanic invaders who had dismantled the western empire to the Slavic peoples that fought Byzantium to a standstill. Conversion often took place both because of the astonishing perseverance of Christian missionaries and the desire on the part of non-Christians to have better political relationships with Christians. That noted, there were also straightforward cases of forced conversions through military force – as described below, the Frankish king Charlemagne exemplified this tendency. Whether through heartfelt conversion or force, by the eleventh century almost everyone in Europe was a Christian, a Latin Christian in the west and an Orthodox Christian in the east.

The Papacy

The Latin Church was distinguished by the at least nominal leadership of the papacy based in Rome – indeed, it was the papal claim to leadership of the Christian Church as a whole that drove a permanent wedge between the western and eastern churches, since the Byzantine emperors claimed authority over both church and state. The popes were not just at the apex of the western church, they often ruled as kings unto themselves, and they always had complex relationships with other rulers. For the entire period of the early Middle Ages (from the end of the western Roman Empire until the eleventh century), the popes were rarely acknowledged as the sovereigns of the Church outside of Italy. Instead, this period was important in the longer history of institutional Christianity because many popes at least claimed authority over doctrine and organization – centuries later, popes would look back on the claims of their predecessors as “proof” that the papacy had always been in charge.

An important example of an early pope who created such a precedent is Gregory the Great, who was pope at the turn of the seventh century. Gregory still considered Rome part of the Byzantine Empire, but by that time Byzantium could not afford troops to help defend the city of Rome, and he was keenly interested in developing papal independence. As a result, Gregory shrewdly played different Germanic kings off against each other and used his spiritual authority to gain their trust and support. He sent missionaries into the lands outside of the kingdoms to spread Christianity, both out of a genuine desire to save souls and a pragmatic desire to see wider influence for the Church.

Gregory’s authority was not based on military power, nor did most Christians at the time assume that the pope of Rome (all bishops were then called “pope,” meaning simply “father”) was the spiritual head of the entire Church. Instead, popes like Gregory slowly but surely asserted their authority by creating mutually-beneficial relationships with kings and by overseeing the expansion of Christian missionary work. In the eighth century, the papacy produced a (forged, as it turned out) document known as the Donation of Constantine in which the Roman emperor Constantine supposedly granted authority over the western Roman Empire to the pope of Rome; that document was often cited by popes over the next several centuries as “proof” of their authority. Nevertheless, even powerful and assertive popes had to be realistic about the limits of their power, with many popes being deposed or even murdered in the midst of political turmoil.

Thus, Christianity spread not because of an all-powerful, highly centralized institution, but because of the flexibility and pragmatism of missionaries and the support of secular rulers (the Franks, considered below, were critical in this regard). All across Europe, missionaries had official instructions not to battle pagan religious practice, but to subtly reshape it. It was less important that pagans understood the nuances of Christianity and more important that they accepted its essential truth. All manner of “pagan” practices, words, and traditions survive into the present thanks to the crossover between Christianity and old pagan practices, including the names of the days of the week in English (Wednesday is Odin’s, or Wotan’s, day, Thursday is Thor’s day, etc). and the word “Easter” itself, from the Norse goddess of spring and fertility named Eostre.

As an example, in a letter to one of the major early English Christian leaders (later a saint), Bede, Pope Gregory advised Bede and his followers not to tear down pagan temples, but to consecrate and reuse them. Likewise, the existing pagan days of sacrifice were to be rededicated to God and the saints. Clearly, the priority was not an attempted purge of pagan culture, but instead the introduction of Christianity in a way that could more easily truly take root. Monks sometimes squabbled about the nuances of worship, but the key development was simply the spread of Christianity and the growing influence of the Church.

Characteristics of Medieval Christianity

The fundamental belief of medieval Christians was that the Church as an institution was the only path to spiritual salvation. It was much less important that a Christian understand any of the details of Christian theology than it was that they participate in Christian worship and, most importantly, receive the sacraments administered by the clergy. Given that the immense majority of the population was completely illiterate, it was impossible for most Christians to have access to anything but the rudiments of Christian belief. The path to salvation was thus not knowing anything about the life of Christ, the characteristics of God, or the names of the apostles, but of two things above all else: the sacraments and the relevant saints to pray to.

The sacraments were, and remain in contemporary Catholicism, the essential spiritual rituals conducted by ordained priests. Much of the practical, day-to-day power and influence exercised by the Church was based on the fact that only priests could administer the sacraments, making access to the Church a prerequisite for any chance of spiritual salvation in the minds of medieval Christians. The sacraments are:

Baptism – believed to be necessary to purge original sin from a newborn child. Without baptism, medieval Christians believed, even a newborn who died would be denied entrance to heaven. Thus, most people tried to have their newborns baptized immediately after birth, since infant mortality was extremely high.

Communion – following the example of Christ at the last supper, the ritual by which medieval Christians connected spiritually with God. One significant element of this was the belief in transubstantiation: the idea that the wine and holy wafer literally transformed into the blood and body of Christ at the moment of consumption.

Confession – necessary to receive forgiveness for sins, which every human constantly committed.

Confirmation – the pledge to be a faithful member of the Church taken in young adulthood.

Marriage – believed to be sanctified by God.

Holy orders – the vows taken by new members of the clergy.

Last Rites – a final ritual carried out at the moment of death to send the soul on to purgatory – the spiritual realm between earth and heaven where the soul’s sins would be burned away over years of atonement and purification.

Unlike in most forms of contemporary Christianity, which tend to focus on the relationship of the individual to God directly, medieval Christians did not usually feel worthy of direct contact with the divine. Instead, the saints were hugely important to medieval Christians because they were both holy and yet still human. Unlike the omnipotent and remote figure of God, medieval Christians saw the saints as beings who cared for individual people and communities and who would potentially intercede on behalf of their supplicants. Thus, every village, every town, every city, and every kingdom had a patron saint who was believed to advocate on its behalf.

Along with the patron saints, the figures of Jesus and Mary became much more important during this period. Saints had served as intermediaries before an almighty and remote deity in the Middle Ages, but the high Church officials tried to advance veneration of Christ and Mary as equally universal but less overwhelming divine figures. Mary in particular represented a positive image of women that had never existed before in Christianity. The growing importance of Mary within Christian practice led to a new focus on charity within the Church, since she was believed to intervene on behalf of supplicants without need of reward.

Medieval Politics

While most Europeans (excluding the Jewish communities, the few remaining pagans, and members of heretical groups) may have come to share a religious identity by the eleventh century, Europe was fragmented politically. The numerous Germanic tribes that had dismantled the western Roman Empire formed the nucleus of the early political units of western Christendom. The Germanic peoples themselves had started as minorities, ruling over formerly Roman subjects. They tended to inherit Roman bureaucracy and rely on its officials and laws when ruling their subjects, but they also had their own traditions of Germanic law based on clan membership.

The so-called “feudal” system of law was one based on codes of honor and reciprocity. In the original Germanic system, each person was tied to his or her clan above all else, and an attack on an individual immediately became an issue for the entire clan. Any dishonor had to be answered by an equivalent dishonor, most often meeting insult with violence. Likewise, rulership was tied closely to clan membership, with each king being the head of the most powerful clan rather than an elected official or even necessarily a hereditary monarchy that transcended clan lines. This unregulated, traditional, and violence-based system of “law,” from which the modern English word “feud” derives, stood in contrast to the written codes of Roman law that still survived in the aftermath of the fall of Rome itself.

Over time, the Germanic rulers mixed with their subjects to the point that distinctions between them were nonexistent. Likewise, Roman law faded away to be replaced with traditions of feudal law and a very complex web of rights and privileges that were granted to groups within society by rulers (to help ensure the loyalty of their subjects). Thus, clan loyalty became less important over the centuries than did the rights, privileges, and pledges of loyalty offered and held by different social categories: peasants, townsfolk, warriors, and members of the church. In the process, medieval politics evolved over time into a hierarchical, class-based structure in which kings, lords, and priests ruled over the vast majority of the population: peasants.

Eventually, the relationship between lords and kings was formalized in a system of mutual protection (or even protection racket). A lord accepted pledges of loyalty, called a pledge of fealty, from other free men called his vassals; in return for their support in war he offered them protection and land-grants called fiefs. Each vassal had the right to extract wealth from his land, meaning the peasants who lived there, so that he could afford horses, armor, and weapons. In general, vassals did not have to pay their lords taxes (all tax revenue came from the peasants). Likewise, the Church itself was an enormously wealthy and powerful landowner, and church holdings were almost always tax-exempt; bishops were often lords of their own lands, and every king worked closely with the Church’s leadership in his kingdom.

Depiction of a feudal pledge of fealty from Harold Godwinson, at the time a powerful Anglo-Saxon noble and later the king of England, to William of Normandy, who would go on to defeat Harold and replace him as king of England. William claimed that Harold had pledged fealty to him, which justified his invasion (while Harold denied ever having done so).

This system arose because of the absence of other, more effective forms of government and the constant threat of violence posed by raiders. The system was never as neat and tidy as it sounds on paper; many vassals were lords of their own vassals, with the king simply being the highest lord. In turn, the problem for royal authority was that many kings had “vassals” who had more land, wealth, and power than they did; it was very possible, even easy, for powerful nobles to make war against their king if they chose to do so. It would take centuries before the monarchs of Europe consolidated enough wealth and power to dominate their nobles, and it certainly did not happen during the Middle Ages.

One (amusing, in historical hindsight) method that kings would use to punish unruly vassals was simply visiting them and eating them out of house and home – the traditions of hospitality required vassals to welcome, feed, and entertain their king for as long as he felt like staying. Kings and queens expected respect and deference, but conspicuously absent was any appeal to what was later called the “Divine Right” of monarchs to rule. From the perspective of the noble and clerical classes at the time the monarch had to hold on to power through force of arms and personal charisma, not empty claims about being on the throne because of God’s will.

Unsurprisingly, there are many instances in medieval European history in which a powerful lord simply usurped the throne, defeated the former king’s forces, and became the new king. Ultimately, medieval politics represented a “warlord” system of political organization, in many cases barely a step above anarchy. Pledges of loyalty between lords and vassals served as the only assurance of stability, and those pledges were violated countless times throughout the period. The Church tried to encourage lords to live in accordance with Christian virtue, but the fact of the matter was that it was the nobility’s vocation, their very social role, to fight, and thus all too often “politics” was synonymous with “armed struggle” during the Middle Ages.

England and France

Anglo-Saxon England

By about 400 CE, the Romans abandoned Britain. Their legions were needed to help defend the Roman heartland and Britain had always been an imperial frontier, with too few Romans to completely settle and “civilize” it outside of southern England. For the next three hundred years, Germanic invaders called the Anglo-Saxons (from whom we get the name “England” itself – it means “land of the Angles”) from the areas around present-day northern Germany and Denmark invaded, raided, and settled in England. They fought the native Britons (i.e. the Romanized, Christian Celts native to England itself), the Cornish, the Welsh, and each other. Those Romans who had settled in England were pushed out, either fleeing to take refuge in Wales or across the channel to Brittany in northern France. England was thus the most thoroughly de-Romanized of the old Roman provinces in the west: Roman culture all but vanished, and thus English history “began” as that of the Anglo-Saxons.

Starting in the late eighth century, the Anglo-Saxons suffered waves of Viking raids that culminated in the establishment of an actual Viking kingdom in what had been Anglo-Saxon territory in eastern England. It took until 879 for the surviving English kingdom, Wessex, to defeat the Viking invaders. For a few hundred years, there was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in England that promoted learning and culture, producing an extensive literature in Old English (the best preserved example of which is the epic poem Beowulf). Raids started up again, however, and in 1066 William the Conqueror, a Viking-descended king from Normandy in northern France, invaded and defeated the Anglo-Saxon king and instituted Norman rule.

France

The former Roman province of Gaul is the heartland of present-day France, ruled in the aftermath of the fall of Rome by the Franks, a powerful Germanic people who invaded Gaul from across the Rhine as Roman power crumbled. The Franks were a warlike and crafty group led by a clan known as the Merovingians. A Merovingian king, Clovis (r. 481 – 511) was the first to unite the Franks and begin the process of creating a lasting kingdom named after them: France. Clovis murdered both the heads of other clans who threatened him as well as his own family members who might take over command of the Merovingians. He then expanded his territories and defeated the last remnants of Roman power in Gaul by the end of the fifth century.

In 500 CE Clovis and a few thousand of his most elite warriors converted to Latin Christianity, less out of a heartfelt sense of piety than for practical reasons: he planned to attack the Visigoths of Spain, Arian Christians who ruled over Latin Christian former Romans. By converting to Latin Christianity, Clovis ensured that the subjects of the Goths were likely to welcome him as a liberator rather than a foreign invader. He was proved right, and by 507 the Franks controlled almost all of Gaul, including formerly-Gothic territories along the border.

The Merovingians held on to power for two hundred years. In the end, they became relatively weak and ineffectual, with another clan, the Carolingians, running most of their political affairs. It was a Carolingian, Charles Martel, who defeated the invading Arab armies at the Battle of Tours (also referred to as the Battle of Poitiers) in 732. Soon afterwards, Charles Martel’s son Pepin seized power from the Merovingians in a coup, one later ratified by the pope in Rome, ensuring the legitimacy of the shift and establishing the Carolingians as the rightful rulers of the Frankish kingdom.

Only the first few kings in the Merovingian dynasty of the Franks were particularly smart or capable. When Pepin seized control in 750 CE, he was merely assuming the legal status that his clan had already controlled behind the scenes for years. The problem facing the Franks was that Frankish tradition stipulated that lands were to be divided between sons after the death of the father. Thus, with every generation, a family’s holdings could be split into separate, smaller pieces. Over time, this could reduce a large and powerful territory into a large number of small, weak ones. When Pepin died in 768, his sons Charlemagne and Carloman each inherited half of the kingdom. When Carloman died a few years later, however, Charlemagne ignored the right of Carloman’s sons to inherit his land and seized it all (his nephews were subsequently murdered).

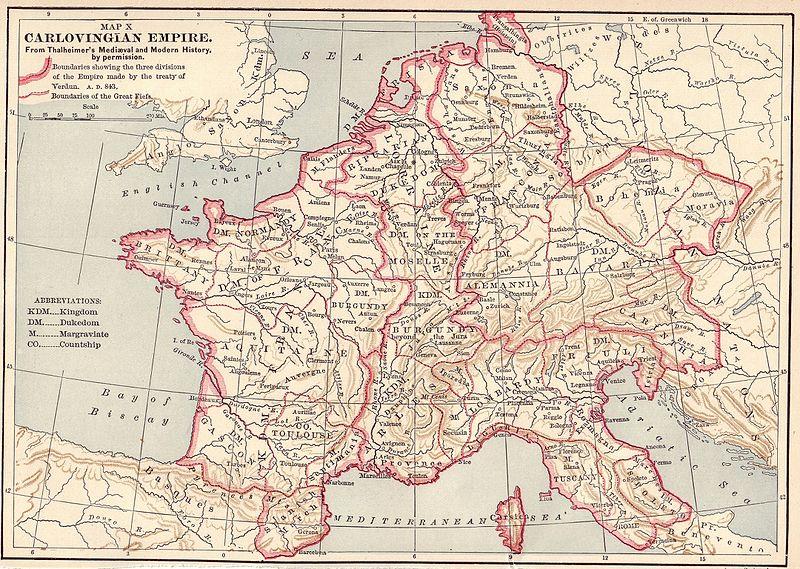

Charlemagne (r. 768 – 814) was one of the most important kings in medieval European history. Charlemagne waged constant wars during his long reign (lasting over 40 years) in the name of converting non-Christian Germans to his east and, equally, in the name of seizing loot for his followers. From his conquests arose the concept of the Holy Roman Empire, a huge state that was nominally controlled by a single powerful emperor directly tied to the pope’s authority in Rome. In truth, only under Charlemagne was the Empire a truly united state, but the concept (with various emperors exercising at least some degree of authority) survived until 1806 when it was finally permanently dismantled by Napoleon. Thus, like the western Roman Empire that it succeeded, the Holy Roman Empire lasted almost exactly 1,000 years.

Charlemagne distinguished himself not just by the extent of the territories that he conquered, but by his insistence that he rule those territories as the new, rightful king. In 773, at the request of the pope, Charlemagne invaded the northern Italian kingdom of the Lombards, the Germanic tribe that had expelled Byzantine forces earlier. When Charlemagne conquered them a year later, he declared himself king of the Lombards, rather than forcing a new Lombard ruler to become a vassal and pay tribute. This was an unprecedented development: it was untraditional for a Germanic ruler to proclaim himself king of a different people – how could Charlemagne be “king of the Lombards,” since the Lombards were a separate clan and kingdom? This bold move on Charlemagne’s part established the answer as well as an important precedent (inspired by Pepin’s takeover): a kingship could pass to a different clan or even kingdom itself depending on the political circumstances. Charlemagne was up to something entirely new, intending to create an empire of various different Germanic groups, with himself (and by extension, the Franks) ruling over all of them.

In 800, Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the pope, Leo III. While Charlemagne’s biographers claimed that this came as a surprise to Charlemagne, it was anything but; Charlemagne completely dominated Leo and looked to use the prestige of the imperial title to cement his hold on power. Charlemagne had already restored Leo to his throne after Leo was run out of Rome by powerful Roman families who detested him. While visiting Italy (which was now part of his empire), Charlemagne was crowned and declared to be the emperor of Rome, a title that no one had held since the western empire fell in 476. Making the situation all the stranger was the fact that the Byzantine emperors considered themselves to be fully “Roman” – from their perspective, Leo’s crowning of Charlemagne was a straightforward usurpation.

Charlemagne’s empire at its height stretched from northern Spain to Bohemia (the present-day Czech Republic). His major areas of conquest were in Central Europe, forming the earliest iteration of “Germany” as a state.

Charlemagne’s empire was a poor reflection of ancient Rome. He had almost no bureaucracy, no standing army, not even an official currency. He spent almost all of his reign traveling around his empire with his armies, both leading wars and issuing decrees. He did insist, eventually, that these decrees be written down, and the form of “code” used to ensure their authenticity was simply that they were written in grammatically correct Latin, something that almost no one outside of Charlemagne’s court (and some members of the Church scattered across Europe) could accomplish thanks to the abysmal state of education and literacy at the time.

Charlemagne organized his empire into counties, ruled by (appropriately enough) counts, usually his military followers but sometimes commoners, all of whom were sent to rule lands they did not have any personal ties to. He protected his borders with marches, lands ruled by margraves who were military leaders ordered to defend the empire from foreign invasion. He established a group of officials who traveled across the empire inspecting the counties and marches to ensure loyalty to the crown. Despite all of his efforts, rebellions against his rule were frequent and Charlemagne was forced to war against former subjects to re-establish control on several occasions.

Charlemagne also reorganized the Church by insisting on a strict hierarchy of archbishops to supervise bishops who, in turn, supervised priests. Likewise, under Charlemagne there was a revival of interest in ancient writings and in proper Latin. He gathered scholars from all of Europe, including areas like England beyond his political control, and sponsored the education of priests and the creation of libraries. He had flawed versions of the Vulgate (the Latin Bible) corrected and he revived disciplines of classical learning that had fallen into disuse (including rhetoric, logic, and astronomy). His efforts to reform Church training and education are referred to by historians as the “Carolingian Renaissance.”

One innovation of note that arose during the Carolingian Renaissance is that Charlemagne instituted a major reform of handwriting, returning to the Roman practice of large, clear letters that are separated from one another and sentences that used spaces and punctuation, rather than the cursive scrawl of the Merovingian period. This new handwriting introduced the division between upper and lower-case letters and the practice of starting sentences with the former that we use to this day.

Ultimately, the Carolingian dynasty lasted for an even shorter period than had the Merovingian. The problem, again, was the Frankish succession law. Without an effective bureaucracy or law code, there was little cohesion to the kingdom, and areas began to split off almost immediately after Charlemagne’s death in 814. The origin of “Germany” (not politically united until 1871, over a thousand years after Charlemagne’s lifetime) was East Francia, the kingdom that Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious left to one of his sons. A different line, not directly descended from the Carolingians, eventually ended up in power in East Francia. Its king, Otto I, was crowned emperor in 962 by the Pope, thereby cementing the idea of the Holy Roman Empire even after Charlemagne’s bloodline no longer ruled it.

Invaders

Post-Carolingian Europe was plunged into a period of disorder and violence that lasted until at least 1100 CE. Even though the specific invaders mentioned below had settled down by about 1000 CE, the overall state of lawlessness and violence lasted for centuries. In addition to attacks by groups like the Vikings, the major political problem of the Middle Ages was that the whole feudal system was one based on violence: lesser lords often had no livelihood outside of war, and they pressured their own lords to initiate raids on nearby lands. “Knights” were often little better than thugs who had the distinction of a minor noble title and the ability to afford weapons and armor. Likewise, one of the legacies of feudal law was the importance placed on honor and retribution; any insult or slight could initiate reprisals or even plunge a whole kingdom into civil war.

Meanwhile, a series of invasions began in the post-Carolingian era. Arab invaders called Saracens attacked southern European lands, even conquering Sicily in the ninth century, while a new group of steppe raiders, the Magyars, swept across Europe in the tenth century, eventually seizing land and settling in present-day Hungary. In Northern Europe, the most significant invaders of the period, however, were the Vikings.

The Vikings

Until the eighth century, the Scandinavian region was on the periphery of European trade, and Scandinavians (the Norse) themselves did not greatly influence the people of neighboring regions. Scandinavian tribesmen had long traded amber (petrified sap, prized as a precious stone in Rome and, subsequently, throughout the Middle Ages) with both other Germanic tribes and even with the Romans directly during the imperial period. While the details are unclear, what seems to have happened is that sometime around 700 CE the Baltic Sea region became increasingly economically significant. Traders from elsewhere in northern Europe actively sought out Baltic goods like furs, timber, fish, and (as before) amber. This created an ongoing flow of wealth coming into Scandinavia, which in turn led to Norse leaders becoming interested in the sources of that wealth. At the same time, the Norse added sails to their unique sailing vessels, longships. Sailed longships allowed the Norse to travel swiftly across the Baltic, and ultimately across and throughout the waterways of Europe.

The Oseberg ship, a surviving Viking longship discovered in a Viking burial mound in Norway and preserved in a dedicated museum in Oslo. Longships allowed the Vikings unprecedented mobility, being capable of both oceanic voyages and of sailing up rivers to raid inland communities.

The Norse, soon known as Vikings, exploded into the consciousness of other Europeans during the eighth century, attacking unprotected Christian monasteries in the 790s, with the first major raid in 793 and follow-up attacks over the next two years. The Vikings swiftly became the great naval power of Europe at the time. In the early years of the Viking period they tended to strike in small raiding parties, relying on swiftness and stealth to pillage monasteries and settlements. As the decades went on, bands of raiders gave way to full-scale invasion forces, numbering in the hundreds of ships and thousands of warriors. They went in search of riches of all kinds, but especially silver, which was their standard of wealth, and slaves, who were equally lucrative. Unfortunately for the monks of Europe, silver was most often used in sacred objects in monasteries, making the monasteries the favorite targets of Viking raiders. The raids were so sudden and so destructive that Charlemagne himself ordered the construction of fortifications at the mouth of the Seine river and began expanding his naval defenses to try to defend against them.

The word “Viking” was used by the Vikings themselves – it either meant “raider” or was a reference to the Vik region that spanned parts of Norway and Sweden. They were known by various other names by the people they raided, from the Middle East to France: the Franks called them “pagani” or “Northmen,” the Anglo-Saxons “haethene men,” the Arabs “al-Majus” (sorcerers), the Germanic tribes “ascomanni” (shipmen), and the Slavs of what would become Russia the “Rus” or “Varangians” (the latter are described below.) Outside of the lands that would eventually become Russia, the Vikings were universally regarded as a terrifying threat, not least because of their staunch paganism and rapacious treatment of Christians.

At their height, the Vikings fielded huge fleets that raided many of the major cities of early medieval Europe and North Africa. By the late ninth century they were formally organized into a “Great Fleet” based in their kingdom in eastern England (they conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia in the 870s). While the precise numbers will never be known, not least because the surviving sources bear a pronounced anti-Viking bias, it is clear that their raids were on scale that dwarfed their earlier efforts. In 844 more than 150 ships sailed up the Garonne River in southern France, plundering settlements along the way. In 845, 800 ships forced the city of Hamburg in northern Germany to pay a huge ransom of silver. In 881, the Great Fleet pillaged across present-day Holland, raiding inland as far as Charlemagne’s capital of Aachen and sacking it. Then, in 885, at least 700 ships sailed up the Seine River and besieged Paris (note that their initial target, a rich monastery, had evacuated with its treasure; the wine cellar was not spared, however). In this attack, they extorted thousands of pounds of silver and gold. Vikings attacked Constantinople at least three times in the ninth and tenth centuries, extracting tribute and concessions in trade, and perhaps most importantly, they came to rule over what would one day become Russia. In the end, the Vikings became increasingly knowledgeable about the places they were raiding, in some cases actually working as mercenaries for kings who hired them to defend against other Vikings.

Starting in roughly 850 CE, the Vikings started to settle in the lands they raided, especially in England, Scotland, the hitherto-uninhabited island of Iceland, and part of France. Outside of Russia, their most important settlement in terms of its historical impact was Normandy in what is today northern France, a kingdom that would go on centuries later to conquer England itself. It was founded in 911 as a land-grant to the Viking king Rollo in order to defend against other Vikings. Likewise, the Vikings settled areas in England that would help shape the English language and literary traditions (for example, though written in the language of the Anglo-Saxons, the famous epic poem Beowulf is about Viking settlers who had recently converted to Christianity). Ultimately, the Vikings became so rich from raiding that they became important figures in medieval trade and commerce, trading goods as far from Scandinavia as Baghdad in the Abbasid Caliphate.

The Vikings were not just raiders, however. They sought to explore and settle in lands that were in some cases completely uninhabited when they arrived, like Iceland. They appear to have been fearless in quite literally going where no one had gone before. Much of their exploration required audacity as well as planning – they were the best navigators of their age, but at times their travels led them to forge into areas completely unknown to Europeans. Vikings were the first Europeans to arrive in North America, with a group of Icelandic Vikings arriving in Newfoundland, in present-day Canada, around the start of the eleventh century. An attempt at colonization failed, however, quite possibly because of a conflict between the Vikings and the Indigenous people they encountered, and the people of the Americas were thus spared the presence of further European colonists for almost five centuries.

In what eventually became Russia, meanwhile, Viking exploration, conquest, and colonization had begun even earlier. The Vikings started traveling down Russian rivers from the Baltic in the mid-eighth century, even before the raiding period began farther west. Their initial motive was trade, not conquest, trading and collecting goods like furs, amber, and honey and transporting them south to both Byzantium and the Abbasid Caliphate. The Vikings were slavers as well, capturing Slavic peoples and selling them in the south. In turn, the Vikings brought a great deal of Byzantine and Abbasid currency to the north, introducing hard cash into the mostly barter-based economies of Northern and Western Europe. Eventually, they settled along their trade routes, often invited to establish order by the native Slavs in cities like Kiev, with the Vikings ultimately forming the earliest nucleus of Russia as a political entity. The very name “Russia” derives from “Rus,” the name of the specific Viking people (originally from Sweden) who settled in the Slavic lands bordering Byzantium.

Eleventh-century illustration of the Varangian Guard, the personal bodyguards of the Byzantine emperors starting in the tenth century. The guard was composed of warriors from the Rus, the Vikings who conquered and then settled in present-day Russia and Ukraine.

As the Vikings settled in the lands they had formerly raided and as powerful states emerged in Scandinavia itself, the Vikings ceased being raiders and came to resemble other medieval Europeans. By the mid-tenth century, the kings of the Scandinavian lands began to assert their control and to reign in Viking raids. Conversion to Christianity, becoming very common by 1000, helped end the raiding period as well. Denmark became a stable kingdom under its king Harald Bluetooth in 958, Norway in 995 under Olaf Tryggvason, and Sweden in 995 as well under Olof Skötkonung. Meanwhile, in northern France, the kingdom of Normandy emerged as the most powerful of the former Viking states, with its duke William the Conqueror conquering England itself from the Anglo-Saxons in 1066.

Conclusion

While the Vikings are important for various reasons – expanding Medieval trade, settling various regions, establishing the first European contact with North America, and founding the first Russian states – they are also included here simply for their inherent interest; their raids and expansion were one of the most striking and sudden in world history.

Far more important to the historical record were the larger patterns of state and society that formed in the early Middle Ages. Above all, the feudal system would have a long legacy in forming the basis of later political structures, and the Latin Church would be the essential European intellectual and spiritual institution for centuries to come. Early medieval Europe was defined by shared cultural traits, above all having to do with religion. Despite having lost the opulence and much of the learning of Rome, medieval Europe was not a static, completely backwards place. Instead, it slowly but surely constructed an entirely new form of society in place of what had been.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Pledge of Fealty – Myrabella

Carolingian Empire – Electionworld

Oseberg Ship – Peulle

Varangian Guard – Public Domain

This chapter has been derived with modifications from Chapter 13: Early Medieval Europe in Western Civilization: A Concise History.