Reading: The Crises of the Middle Ages

Christopher Brooks

From a very “high level” perspective, the years between about 1000 CE – 1300 CE were relatively good ones for Europe. The medieval agricultural revolution sparked an expansion of population, urbanization, and economics, advances in education and scholarship paid off in higher literacy rates and a more sophisticated intellectual life, and Europe was free of large-scale invasions. Starting in the mid-thirteenth century in Eastern Europe, and spreading to Western Europe in the fourteenth century, however, a series of crises undermined European prosperity, security, and population levels. Historians refer to these events as the “crises of the Middle Ages.”

The Mongols

The Mongols are not always incorporated into the narrative of Western Civilization, because despite the enormous breadth of their empire under Chinggis (also Anglicized as Genghis, although the actual pronunciation in Mongolian is indeed Chinggis) Khan and his descendants, most of the territories held by the Mongols were in Asia. The Mongols, however, are entirely relevant to the history of Western Civilization, both because they devastated the kingdoms of the Middle East at the time and because they ultimately set the stage for the history of early-modern Russia.

The Mongols and the Turks are related peoples from Central Asia going back to prehistory. They were nomads and herders with very strong traditions of horse riding, archery, and warfare. In general, the Turks lived in the western steppes (steppe is the term for the enormous grasslands of Central Asia) and the Mongols in the eastern steppes, with the Turks threatening the civilizations of the Middle East and Eastern Europe and the Mongols threatening China. A specific group of Turks, the Seljuks, had already taken over much of the Middle East by the eleventh century, and over the next two hundred years they deprived the Byzantine Empire of its remaining holdings outside of Constantinople and its immediate surroundings.

Meanwhile, in 1206 the Mongols elected a leader named Temujin (b. 1167) “Khan,” which simply means “lord” or “warlord.” The election was the culmination of years of battles and struggles between Temujin and various rival clan leaders. By the time he united the Mongols under his rule, he had already overcome numerous setbacks and betrayals, described years later in a major history commissioned by the Mongol rulers, the Secret History of the Mongols. After his election as Khan, he set his sites on the lands beyond Mongolia and eventually became known as Chinngis Khan, meaning “universal lord.” He united both the Mongols and various Turkic clans, then launched the single most successful campaign of empire-building in world history.

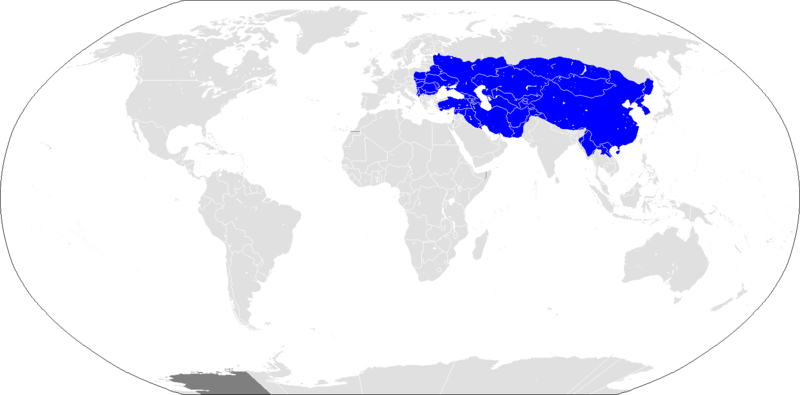

Chinngis personally oversaw the beginning of the expansion of the “Mongol Horde” across all of Central Asia as far as the borders of Russia and China. Over the following decades, Mongol armies conquered all of Central Asia itself, Persia (in 1221), northern China (in 1234), Russia (in 1241), the Abbasid Caliphate (in 1258), and southern China (in 1279). Importantly, most of these conquests occurred under Chinngis’s sons and grandsons (he died in 1227), demonstrating that Mongol military prowess was not dependent on his personal genius. Ultimately, the Mongol empires (a series of “Khanates” divided between the sons and grandsons of Chinggis) stretched from Hungary to Anatolia and from Siberia to the South China Sea.

The Mongol Empire at its height, under Temujin’s grandson Kublai Khan, was the largest land empire in world history.

Mongol military discipline was extraordinary by pre-modern standards. Starting with Chinngis himself, all Mongols were beholden to a code of conduct and laws called the Yasa (historians debate whether or not the Yasa was a codified set of laws or just a set of traditions). They were divided into units divisible by ten, from hundred-man companies to ten-thousand-man armies called Tumen. Since clan divisions had always undermined Mongol unity in the past, Chinngis deliberately placed members of a given clan in different Tumen to water-down clan loyalty and encourage his warriors to think of themselves as part of something greater than their clans.

Mongols had strict regulations for order of march, guard duty, and maintenance of equipment. All men were expected to serve in the armies, and the Mongols quickly and efficiently plundered the areas they conquered to supply their troops. Mongols trained relentlessly; during the brief periods of peace they took part in great hunts of animals which were then critiqued by their commanders. Each warrior had several horses, all trained to respond to voice commands, and in battle Mongol armies were coordinated by signal flags.

The Mongols also made extensive use of spies and intelligence to gather information about areas they planned to attack, interviewing merchants and travelers before they arrived. They were noteworthy for being willing to change their tactics to suit the needs of a campaign, using siege warfare, terror tactics, even biological warfare (flinging plague-ridden corpses over city walls) as necessary. Once the Mongols had conquered a given territory, they would deport and use soldiers and engineers from the conquered peoples against new targets: Persian siege engineers were used to help the conquest of China, and later, Chinese officials were used to help extract taxes from what was left of Persia.

The Mongol horde often devastated the lands it conquered. Some, like the Central Asian kingdom of Khwarizm, were so devastated that the areas it encompassed never fully recovered. Chinngis himself believed that civilization was a threat that might soften his men, so he had whole cities systematically exterminated; in some of their invasions the Mongols practiced a medieval form of what we might justifiably call genocide. Fortunately for the areas conquered by the Mongols, however, under Chinngis’s sons and grandsons this policy of destruction gave way to one of (often still vicious) economic exploitation and political dominance.

The Mongols in Eastern Europe

In 1236, after years of careful planning, the Mongols attacked Russia. Russia was not a united kingdom – instead, each major city was ruled by a prince, and the princes often fought one another. When the Mongols arrived, the Russian principalities were divided and refused to fight together, making them easy prey for the unified and highly-organized Mongol army. By 1240, all of the major Russian cities had been either destroyed or captured – the city of Vladimir was burned with its population still inside.

In 1241 the Mongols invaded Poland and Hungary simultaneously. Here, too, they triumphed over tens of thousands of European knights and peasant foot-soldiers. Both kingdoms would have been incorporated into the Mongol empire if not for the simple fact that the Great Khan Ogodei (Chinngis’s third son, who had become Great Khan following Chinngis) died, and the European Tumen were recalled to the Mongol capital of Karakorum. This event spared what very well could have been a Mongol push into Central Europe itself; the pope at the time called an anti-Mongol crusade and those Europeans who understood the scope of the threat were terrified of the prospect of the Mongols marching further west. As it happens, the Mongols never came back.

The Mongols were finally stopped militarily by the Mamluk Turks, the rulers of Egypt as of the thirteenth century, who held back a Mongol invasion in 1260. By then, the inertia of the Mongol conquests was already slowing down as the great empire was divided between different grandsons of Temujin; the Mamluk victory did not represent the definitive defeat of the Mongol horde as a whole, just a check on Mongol expansion in one corner of the vast Mongol empire. By then, the Mongol khanates had become truly independent from one another, with Mongol rule eventually collapsing over time (a process that happened in just a few decades in some places, but took centuries in others – Russia was not free of Mongol rule until the second half of the fifteenth century).

Mongol rule had mixed consequences for both Asian and European history. There was a beneficial stabilization in the trade that crossed the west – east axis in Eurasia as a continent, as Silk Road traders enjoyed a relatively peaceful and stable route. It also terrified Europeans, who heard travelers’ tales of the non-Christian “Tatars” in the east who had crushed all opposition, and in Russia it created a complex political situation in which the native Slavic peoples were forced to pay tribute to Mongol lords. To this day, the period of Mongol rule is often taught in Russia as the period of the “Tatar Yoke,” when any hope of progress for Russia was suspended for centuries while the rest of Europe advanced; while that may be a bit of an exaggeration, it still has a kernel of truth.

The Black Death

Historians have now arrived at a consensus that the deadliest epidemic in medieval and early-modern history began in the Mongol khanates and spread west: the Black Death, or simply “the plague,” of the fourteenth century. The plague devastated the areas it affected, none more so than Europe. That devastation was in large part due to the vulnerability of the European population to disease thanks both to poor harvests and the lack of practical medical knowledge.

A series of bad harvests led to periods of famine in Europe starting in the early fourteenth century. Conditions in some regions were so desperate that peasants reportedly resorted to cannibalism on occasion. When harvests were poor, Europeans not only died outright from famine, but those who survived were left even more vulnerable to epidemics because of weakened immune systems. By the time the plague arrived in 1348, generations of people were malnourished and all the more susceptible to infection as a result.

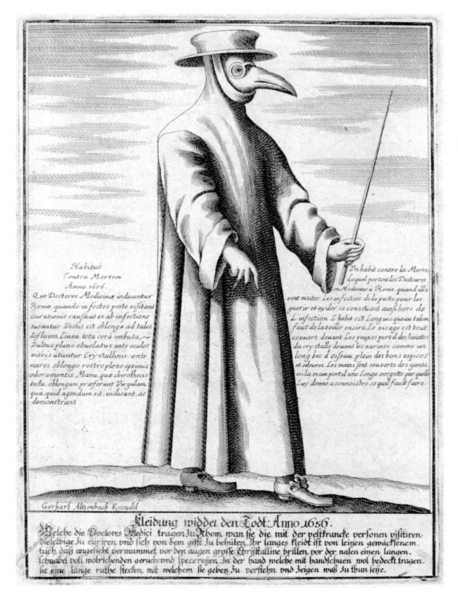

Medicine was completely ineffective in holding the plague in check. Europeans did not understand contagion – they knew that disease spread, but they had absolutely no idea how to prevent that spread. The prevailing medical theory was that disease was spread by clouds of foul-smelling gases called “miasmas,” like those produced by stagnant water and decay. Thus, people sincerely believed that if one could avoid the miasmas (which of course never actually existed), they could avoid sickness. Over the centuries, doctors advocated various techniques that were meant to dispel the miasmas by introducing other odors, including leaving piles of onions on the streets of plague-stricken neighborhoods and, starting in the seventeenth century, wearing masks that resembled the heads of birds, with the “beaks” stuffed with flower petals.

A later depiction of a doctor in the midst of a plague epidemic.

Not surprisingly, given the dearth of medical knowledge, epidemics of all kinds regularly swept across Europe. When harvests failed, the poor often went to the cities in search of some kind of respite, either work or church-based charity. In 1330, for instance, the official population of the northern Italian city of Florence was 100,000, but a full 20,000 were paupers, most of whom had come from the countryside seeking relief. The cities became incubators for epidemics that were even more intense than those that affected the countryside.

Thus, a vulnerable and, in terms of medicine, ignorant population fell victim to the virulence of the Black Death from 1348 to 1351. Historians still debate as to exactly which (identifiable with contemporary medical knowledge) disease or diseases the the Black Death consisted of, but the prevailing theory is that it was bubonic plague. Bubonic plague is transmitted by fleas, both those carried by rats and transmitted to humans, and on fleas exclusive to humans. In the unsanitary conditions of medieval Europe, there were both rats and fleas everywhere. In turn, many victims of bubonic plague developed the “pneumonic” form of the disease, spread by coughing, which made it both incredibly virulent and lethal (about 90% of those who developed pneumonic plague died).

The theory the Black Death was the bubonic plague runs into the problem that modern outbreaks of bubonic plague do not seem to travel as quickly as did the Black Death, although that almost certainly has much to do with the vastly more effective sanitation and treatment available in the modern era as compared to the medieval setting of the Black Death. One hypothesis is that those with bubonic plague may have caught pneumonia as a secondary infection, and that pneumonia was thus another lethal component of the Black Death. Regardless of whatever disease or combination of diseases the Black Death really was, the effects were devastating.

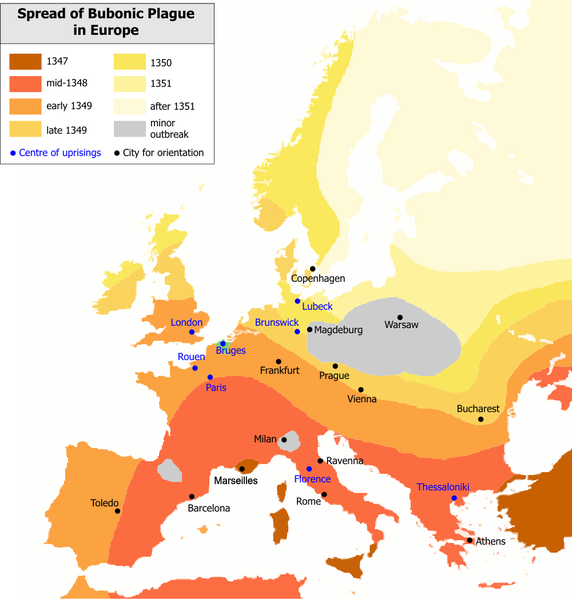

The plague exploded across Europe starting at the end of the 1340s. All of Southern Europe was affected in 1348; it spread to Central Europe and England by 1349 and Eastern Europe and Scandinavia by 1350. It went on to spread even further and continued to fester until 1351, when it had killed so many people that the survivors had developed a resistance to it. The death toll was astonishing: in the end, the Black Death killed about one-third of the population of Europe in just three years (that is a conservative estimate – some present-day historians have calculated that it was closer to half!). Some cities lost over half of their population; there are even cases of villages where there was only a single survivor. This was an enormous demographic shift in a very short amount of time that had lasting consequences for European society, thanks mostly to the labor shortage that it introduced.

The plague’s spread, from south to north, over the course of just a few years. The section marked in grey is incorrectly labeled “minor outbreak”: in fact, while data is difficult to come by for that region, it seems clear that the plague hit just as hard there as elsewhere in Europe.

The only somewhat effective response to the Black Death was the implementation of quarantines. The more fast-acting city governments of Europe locked those who had plague symptoms in their homes, often for more than a month, and sometimes whole neighborhoods or districts were placed under quarantine. In the countryside, people refused to travel to larger cities and towns out of fear of infection. Even though quarantines slowed the spread of the plague in some cases, overall they did little but delay it.

More common than practical measures like quarantines, however, was prayer and the search for scapegoats to blame for the devastation. The spiritual reaction to the plague was, among Christian Europeans, to implore God for relief, beg for forgiveness, and to look to outsiders to blame. Building on the murderous anti-Semitism that had begun in earnest during the period of the crusades, Jews were often the victims of this phenomenon. There was a huge spike in anti-Semitic riots during plague outbreaks, as Jews were blamed for somehow bringing the plague (a frequent accusation was that Jews had poisoned wells), and thousands of Jews were massacred as a result.

Religious movements emerged in response to the plague as well, like the Flagellants: groups of penitents who roamed the countryside, villages, and towns whipping themselves and begging God for forgiveness. Many people sincerely believed that the Black Death was the opening salvo of the End Times, since the history of Europe in the fourteenth century so clearly involved both famine and pestilence – two of the four “horsemen” that were to accompany the end times according to the Bible (the others, war and death, were ever-present as well).

The Black Death ended in 1351, but the plague returned roughly every twenty years in some form. Some cases were as devastating, at least in limited areas, as the Black Death had been. The plague did not stop entirely until the early eighteenth century – to this day it is not clear what brought an end to large-scale plague outbreaks, although one theory is that a species of brown rat that was not as vulnerable to the plague overwhelmed the older black rats that had infested Europe.

Effects of the Plague’s Aftermath

Ironically, the immediate economic effects of the plague after it ended were largely positive for many people. The demographic consequences of the Black Death, namely its enormous death toll, resulted in a labor shortage across all of Europe. The immediate effect was that lords tried to keep their peasants from fleeing the land and to keep wages at the low levels they had been at before the plague hit, sparking various peasant uprisings. Even though those uprisings were generally bloodily put down in the end, the overall trend was that laborers had to be paid more; their labor was simply more valuable. In the decades that followed, then, many peasants benefited from higher prices for their labor and their crops.

Another group that benefited was women. For roughly a century after the plague, women had more legal rights in terms of property ownership, the right to participate in commerce, and land ownership, than they had enjoyed before the plague’s outbreak. Women were even able to join certain craft guilds for a time, something that was almost unheard of earlier. The reason for this temporary improvement in the legal and economic status of women was precisely the same as that of peasants: the labor shortage.

The plague also ushered in a cultural change that came about because of the prevalence of death in the fourteenth century. Europeans became so used to death that they often depicted it graphically and quite terribly in art. Paintings, stories, and theatrical performances emerged having to do with the “dance of death,” a depiction of the futility of worldly possessions and status vis-à-vis the inevitability of death. Likewise, graves and mausoleums came to be decorated with statues of grotesque skeletons and writhing bodies. When people were dying, their families and friends were supposed to come and view them, inoculating everyone present against the temptation to enjoy life too much and encouraging them to greater focus on preparing their souls for the afterlife.

The dance of death, with this image produced decades after the Black Death had already run its course.

The 100 Years’ War

The plague happened near the beginning of the conflict between England and France remembered as the Hundred Years’ War, which lasted from 1337 – 1453. That conflict was not really one war, but instead consisted of a series of battles and shorter wars between the crowns of England and France interrupted by (sometimes fairly long) periods of peace.

The war began because of simmering resentments and dynastic politics. The root of the problem was that the English kings were descendants of William the Conqueror, the Norman king who had sailed across the English Channel in 1066 and defeated the Anglo-Saxon king who then ruled England. From that point on, the royal and noble lines of England and France were intertwined, and as marriage between both nobles and royalty often took place across French – English lines, the inheritance of lands and titles in both countries was often a point of contention. The culture of nobility in both countries was so similar that the “English” nobles generally spoke French instead of English in day-to-day life.

This confusion very much extended to the kings themselves. The English royal line (the Plantagenets) often enjoyed pledges of fealty from numerous “French” nobles, and “English” kings often thought of themselves as being as much French as English – the English King Richard the Lion-Hearted, for instance, spent most of his career in France battling for control of more French territory. Likewise, a large region in southwestern France, Aquitaine, was formally the property of the English royal line, with the awkward caveat that, while a given English king might be sovereign in England, his lordship of Aquitaine technically made him the vassal of whoever the French king happened to be. Thus, hundreds of years after William’s conquest, the royal and noble lines of England and France were often hard to distinguish from one another.

The war began in the aftermath of the death of the French King Charles IV in 1328. The king of England, Edward III, was next in line for succession, but powerful members of the French nobility rejected his claim and instead pledged to give the crown to a French noble of the royal line named Philip VI. When Philip began passing judgments to do with the English-controlled territory of Aquitaine, Edward went to war, sparking the Hundred Years’ War itself.

The war itself consisted of a series of raids and invasions by English forces punctuated by the occasional large battle. English kings and knights kept the war going because it was a way to enrich themselves – they would arrive in France with a moderately-sized force of armed men to loot and pillage. English forces tended to be better organized than were their French counterparts, so even France’s much greater wealth and size did prevent major English victories. The most famous of those victories was the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, in which a smaller English force decimated the elite French cavalry through effective use of longbows, a weapon that could transform an English peasant into more than the equal of a mounted French knight. The aftermath of Agincourt saw most of the French nobility accept the English king, Henry V, as the king of France. Henry V promptly died, however, and the conflict exploded into a series of alliances and counter-alliances between rival factions of English and French nobles (one French territory, Burgundy, even declared its independence from France and became a staunch English ally for a time).

Decades into the war, the French received an unexpected boost in their fortunes thanks to the intervention of one of the future patron saints of France itself: Joan of Arc. Joan was a peasant girl who walked into the middle of the conflict in 1429, supporting the French Dauphin (heir) Charles VII. Joan reported that she had received a vision from God commanding her to help the French achieve victory against the invading English. French forces rallied around Joan, with Joan herself leading the French forces in several battles. Remarkably, despite being a teenage peasant with no military background, she proved capable at aiming catapults, making tactical decisions, and rallying the French troops to victory. Buoyed by the sense that God was on their side, French forces prevailed. Even though she was soon captured and handed over to the English for trial and execution as a witch by the Burgundians, Joan became a martyr to the French cause and, eventually, one of the most significant French nationalist symbols. By 1453, the French forces finally ended the English threat.

An illustration of Joan of Arc from 1505, just under 60 years after the end of the war.

The war had a devastating effect on France. Between the fighting and the plague, its population declined by half. Many French regions suffered economically as luxury trades shut down and whole regions were devastated by the fighting. The French crown introduced new taxes, such as the Gabelle (a tax on salt) and the Taille (a household tax) that further burdened commoners. On the cultural front, the English monarchy and nobility severed their ties with France and high English culture began to self-consciously reshape itself as distinctly English rather than French, leading among other things to the use of the English language as the language of state and the law for the first time.

The Babylonian Captivity and the Great Western Schism

Even as the French and English were at each other’s throats, the Catholic Church fell into a state of disunity, sometimes even chaos. The cause was one of the most peculiar episodes in late medieval European history: the “Babylonian Captivity” of the popes in the fourteenth century. The term originally referred to the Biblical story of the Jews’ enslavement by the Babylonian Empire in the sixth century BCE, but the late-medieval Babylonian Captivity refers instead to the period during which the popes no longer lived in their traditional residence in Rome.

The context for this strange event was the state of the Catholic Church as of the early fourteenth century. The Church was a very diverse, and somewhat diffuse, institution. Due to the simple geographical distance between Rome and the kingdoms of Europe, the popes did not exercise much practical authority over the various national churches, and high-level churchmen in European kingdoms were often more closely associated with their respective kings than with Rome. Likewise, there were many times during the Middle Ages when individual popes were weak and ineffectual and could not even command obedience within the church hierarchy itself.

Over the centuries the papacy struggled, and often failed, to assert its control over the Church as an institution and to hold the pretensions of kings in check. Those weaknesses were reflected in a simple fact: there had been a number of times over the centuries in which there were rival popes, generally appointed by compliant church officials who answered to kings. Obviously, having rival popes undermined the central claim of the papacy to complete authority over the Church itself and over Christian doctrine in the process (let alone the occasional insistence by popes that their authority superseded that of kings – see below).

The Babylonian Captivity began when Pope Boniface VIII issued a papal bull (formal commandment) in 1303 to the effect that all kings had to acknowledge his authority over even their own kingdoms, a challenge he issued in response to the taxes kings levied on church property. Unfortunately for Boniface, he lacked both influence with the monarchs of Europe and the ability to defend himself. Infuriated, the French king, Philip IV, promptly had the pope arrested and thrown in prison; he was released months later but promptly died.

Philip supported the election of a new pope, Clement V, in 1305. Clement was a Frenchman with strong ties to the French nobility. At the time, Rome was a very dangerous city, with rival noble families literally fighting in the streets over various feuds, so Clement moved himself and the papal office to the French city of Avignon, which was much more peaceful. This created enormous concern among non-French church officials (most of them Italian), who feared that the French king, then the most powerful ruler in Europe, would have undue influence over the papacy. Their fears seemed confirmed when Clement started appointing new cardinals, a pattern that ultimately saw 113 French cardinals out of the 134 who were appointed in the following decades.

From 1305 to 1378, the popes continued to live and work in Avignon (despite the English invasions of the 100 Years’ War). They were not directly controlled by the French king, as their opponents had feared, but they were definitely influenced by French politics. They also came to accept bribes and kickbacks for the appointment of priests and bishops, along with shady schemes with Church lands. This situation was soon described as a new Babylonian Captivity by clerics and laypeople alike (especially in Italy), comparing the presence of the papacy in France to the enslavement of the ancient Jews in Babylon.

In 1378, the new pope, Urban VI, announced his intention to move the papacy back to Rome. As rival factions developed within the upper levels of the Church hierarchy, a group of French cardinals elected another, French, pope (Clement VII), and Europe thus was split between two rival popes, both of whom excommunicated each other as a heretic and impostor (the term used at the time was “antipope.”) This led to the Great Western Schism, a period from 1378 to 1417 during which there were as many as three rival popes vying for power. For almost forty years, the church was a battlefield between both rival popes and their respective followers, and laypeople and monarchs alike were generally able to go about their business with little fear of papal intervention.

The Great Western Schism finally ended after a series of church councils, the Conciliar Movement, succeeded in establishing the authority of a single pope in 1417. The movement elected a new pope, Martin V, and made the claim that church councils could and should hold the ultimate authority over papal appointments – this concept was known as the via consilii, the existence of a great council with binding powers over the church’s leadership. This, however, undermined the very concept of what the papacy was: the “Doctrine of the Keys” held that the pope’s authority was passed down directly from Christ, and that even if councils could play a role in the practical maintenance of the church, the pope’s authority was not based on their approval. Ultimately, a powerful pope, Eugene IV, reconfirmed the absolute power of the papacy in 1431. Thus, this attempt at reform failed in the end, inadvertently setting the stage for more radical criticisms of papal power in the future.

The most important consequence of the Babylonian Captivity and the Great Western Schism was simple: the moral and spiritual authority of the church hierarchy was seriously undermined. While no one (yet) envisioned rejecting the authority of the Church altogether, many people regarded the Church’s leadership as just another political institution.

Conclusion

Some of the trends, patterns, and phenomena that were to take shape during the Renaissance era which began around 1300 began in the midst of the crises of the Middle Ages. France and England emerged from the 100 Years War to become stronger, more centralized states (although it took a civil war in England to get there, described in a subsequent chapter). The labor shortage in the aftermath of the Black Death spurred a period of modest economic growth. And, while European culture may have become more pessimistic and xenophobic as a whole, one region was rising to wealth and prominence precisely because of its long-distance trade and cultural connections: Northern Italy. It was there that the Renaissance began.

Image Citations (Creative Commons):

Mongol Empire – Spesh531

Plague Doctor – Ian Spackman

Plague Map – Bunchofgrapes

Dance of Death – Il Dottore

Joan of Arc – Public Domain

This chapter has been derived with modifications from Chapter 2: The Crises of the Middle Ages in Western Civilization: A Concise History.