Reading: Renaissance Era States

Christopher Brooks

The Renaissance was originally an Italian phenomenon, due to the concentration of wealth and the relative power of the city-states of northern Italy. Renaissance thought spread, however, thanks to interactions between the kings and nobility of the rest of Europe and the elites of the Italian city-states, especially after a series of wars at the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century saw the larger monarchies of Europe exert direct political control in Italy.

The End of the Italian Renaissance

Detailed below, a new regional power arose in the Middle East and spread to Europe starting in the fourteenth century: the Ottoman Turks. In 1453, the ancient Roman city of Constantinople fell to the Turks, by which time the Turks had already seized control of the entire Balkan region (i.e. the region north of Greece including present-day Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Albania, and Macedonia). The rise in Turkish power in the east spelled trouble for the east-to-west trade routes the Italian cities had benefited from so much since the era of the crusades, and despite deals worked out between Venice and the Ottomans, the profits to be had from the spice and luxury trade diminished (at least for the Italians) over time.

By the mid-fifteenth century, northern manufacturing began to compete with Italian production as well. Particularly in England and the Netherlands, northern European crafts were produced that rivaled Italian products and undermined the demand for the latter. Thus, the relative degree of prosperity in Italy vs. the rest of Europe declined going into the sixteenth century.

The real killing stroke to the Italian Renaissance was the collapse of the balance of power inaugurated by the Peace of Lodi. The threat to Italian independence arose from the growing power of the Kingdom of France and of the Holy Roman Empire, already engaged in intermittent warfare to the north. The French king, Charles VIII, decided to seize control of Milan, citing a dubious claim tied up in the web of dynastic marriage, and a Milanese pretender invited in the French to help him seize control of the despotism in 1494. All of the northern Italian city-states were caught in the crossfire of alliances and counter-alliances that ensued; the Medici were exiled from Florence the same year for offering territory to the French in an attempt to get them to leave Florence alone.

The result was the Italian Wars that ended the Renaissance. The three great powers of the time, France, the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain, jockeyed with one another and with the papacy (which behaved like just another warlike state) to seize Italian territory. Italy became a battleground and, over the next few decades, the independence of the Italian cities was either compromised or completely extinguished. Between 1503 – 1533, one by one, the cities became territories or puppets of one or the other of the great powers, and in the process the Italian countryside was devastated and the financial resources of the cities were drained. In the aftermath of the Italian Wars, only the Papal States of central Italy remained truly politically independent, and the Italian peninsula would not emerge from under the shadow of the greater powers to its north and west until the nineteenth century.

That being noted, the Renaissance did not really end. What “ended” with the Italian Wars was Italian financial and commercial dominance and the glory days of scholarship and artistic production that had gone with it. By the time the Italian Wars started, all of the patterns and innovations first developed in Italy had already spread north and west. In other words, “The Renaissance” was already a European phenomenon by the late fifteenth century, so even the end of Italian independence did not jeopardize the intellectual, commercial, and artistic gains that had originally blossomed in Italy.

The greatest achievement of the Italian Renaissance, despite the higher profile given to Renaissance art, was probably humanistic education. The study of the classics, a high level of literary sophistication, and a solid grounding in practical commercial knowledge (most obviously mathematics and accounting) were all combined in humanistic education. Royal governments across Europe sought out men with humanistic education to serve as bureaucrats and officials, even as merchants everywhere adopted Italian mercantile practices for their obvious benefits (e.g. the superiority of Arabic numerals over Roman ones, the crucial importance of accurate bookkeeping, etc.). Thus, while not as glamorous as beautiful paintings or soaring buildings, the practical effects of humanistic education led to its widespread adoption almost everywhere in Europe.

Politics: The Emergence of Strong States

While the city-states of northern Italy were enjoying the height of their prosperity in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, northern and western Europe was divided between a large number of fairly small principalities, church lands, free cities, and weak kingdoms. As described in previous chapters, the medieval system of monarchy was one in which kings were really just the first among nobles; their power was based primarily on the lands they owned through their family dynasty, not on the taxes or deference they extracted from other nobles or commoners. In many cases, powerful nobles could field personal armies that were as large as those of the king, especially since armies were almost always a combination of loyal knights (by definition members of the nobility) on horseback, supplemented by peasant levies and mercenaries. Standing armies were almost nonexistent and wars tended to be fairly limited in scale as a result.

During the late medieval and Renaissance periods, however, monarchs began to wield more power and influence. The long-term pattern from about 1350 – 1500 was for the largest monarchies to expand their territory and wealth, which allowed them to fund better armies, which led to more expansion. In the process, smaller states were often absorbed or at least forced to do the bidding of larger ones; this is true of the Italian city-states and formerly independent kingdoms like Burgundy in eastern France.

The New Kingdoms: Spain, England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire

Spain

In the Middle Ages, Spain had been divided between small Christian kingdoms in the north and larger Muslim ones in the south. The Crusades were part of a centuries-long series of wars the Christian Spaniards called the Reconquest, which reached its culmination in the late fifteenth century. Spain became a powerful and united kingdom for the first time when the monarchs of two of the Christian kingdoms were married in 1479: Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon. During their own lifetimes Aragon and Castile remained independent of one another, though obviously closely allied, but the marriage ensured that Isabella and Ferdinand’s daughter Joanna and her son Charles V would go on to rule over Spain as a single, unified kingdom.

The “Catholic monarchs” as they were called were determined to complete the Reconquest of the Iberian peninsula, and in 1492 they succeeded in doing so, capturing Grenada, the last Muslim kingdom. Full of crusading zeal, they immediately set about rooting out “heretics” like the kingdom’s large Jewish population, forcing Jews to either convert to Catholicism or leave the kingdom that same year. In 1502 they gave the same ultimatum to the hundreds of thousands of Muslims as well. Most Jews and Muslims chose to go into exile, most to the relatively tolerant and economically prosperous kingdoms of North Africa or the (highly tolerant by the standards of European kingdoms at the time) Ottoman Empire.

The Spanish monarchs also attacked the privileges of their own nobility, in some cases literally destroying the castles of defiant nobles and forcing nobles to come and pay homage at court (in the process neutralizing them as a threat to their authority). After Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World in 1492, recalcitrant nobles were often shipped off as governors of islands thousands of miles away. They also succeeded in reforming the tax system to get access to more revenue, especially by taxing trade, and so by 1500 the Spanish army was the largest and most feared in Europe.

Queen Isabella deserves special attention. She was unquestionably one of the most significant “queens regnant” (a queen with genuine political power, not merely the royal wife of a king) of the entire Renaissance era. She tended to rule with more boldness and vision than did Ferdinand, personally leading Castilian troops during the last years of the Reconquest, sponsoring Columbus’s voyage, and presiding over the larger and richer of the two major Spanish kingdoms. Simply put, Isabella exemplified the trend of Renaissance rulers asserting greater power over their respective kingdoms than had the monarchs of earlier eras.

In many ways, the sixteenth century was “the Spanish century,” when Spain was the most prosperous and powerful kingdom in Europe, especially after the flow of silver from the Americas began. Spain went from a disunited, war-torn region to a powerful and relatively centralized state in just a few decades.

England

It initially seemed like England would follow a very different path than did Spain; while Spain was becoming stronger and more unified, England plunged into decades of civil war before a strong monarchy emerged. After the end of the Hundred Years’ War, English soldiers and knights returned with few prospects at home. They enlisted in the service of rival nobles houses, ultimately fueling a conflict within the royal family between two different branches, the Lancasters and the Yorks. The result was a violent conflict over the crown called the War of the Roses, lasting from 1455 – 1485. Ultimately, a Welsh prince named Henry Tudor who was part of the extended family of Lancasters defeated Richard III of York and claimed the throne as King Henry VII.

Henry VII proved extremely adept at controlling the nobility, in large part through the Star Court, a royal court used to try nobles suspected of betraying him or undermining the king’s authority. The Star Court’s judges were royal officials appointed by Henry, and it regularly used torture to obtain confessions from the accused. Henry also seized the lands of rebellious lords and banned private armies that did not ultimately report to him. The result was a streamlined political system under his control and a nobility that remained loyal to him as much out of fear as genuine allegiance. The sixteenth century saw Henry’s line, the Tudors, establish an increasingly powerful English state, largely based on a pragmatic alliance between the royal government and the gentry, the landowning class who exercised the lion’s share of political power at the local level.

That alliance was shored up by staggering levels of official violence through law enforcement and the brutal suppression of popular uprisings. For example, roughly 20,000 people were executed in England in the 30 years between 1580 and 1610, a rate which if applied to the present-day United States would amount to 46,000 executions a year. Criminals who were not hanged or beheaded were routinely whipped, branded, or mutilated in order to inspire (in so many words from magistrates at the time) terror among other potential law-breakers or rebels. Nevertheless, despite that violence and its relatively small population, England did emerge as a powerful and centralized kingdom by the middle of the sixteenth century.

France

France emerged at the same time as the only serious rival to Spain. The French king Charles VII (r. 1422 – 1461), the same king who finally won the 100 Years’ War for France and expelled the English, created the first French professional army that was directly loyal to the crown. He funded it with the taille, the direct tax on both peasants and nobles that had originally been authorized by the nobility and rich merchants of France during the latter part of the Hundred Years’ War, and the gabelle, the salt tax. Each of these taxes were supposed to be temporary sources of revenue to support the war effort.

Charles’s successor Louis XI (r. 1431 – 1483), however, managed to make the new taxes permanent. In other words, he converted what had been an emergency wartime revenue stream into a permanent source of money for the monarchy. He was called “The Spider” for his ability to trap weak nobles and seize their lands under various legal pretenses. He also expelled the Jews of France as heretics, seizing the wealth of Jewish money-lenders in the process, and he even liquidated the old crusading order of the Knights Templar headquartered in France, seizing their funds as well. By the time of his death, the French monarchy was well funded and exercised increasing power over the nobility and towns.

The Holy Roman Empire

In contrast to the growth of relatively centralized states in Spain, England, and France, the German lands of central Europe remained fragmented. The very concept of “Germany” was an abstraction during the Renaissance era. Germany was simply a region, a large part of central Europe in which most, but not all, people spoke various dialects of the German language. It was politically divided between hundreds of independent kingdoms, city-states, church lands, and territories. Its only overarching political identity took the form of that most peculiar of early-modern European states: the Holy Roman Empire.

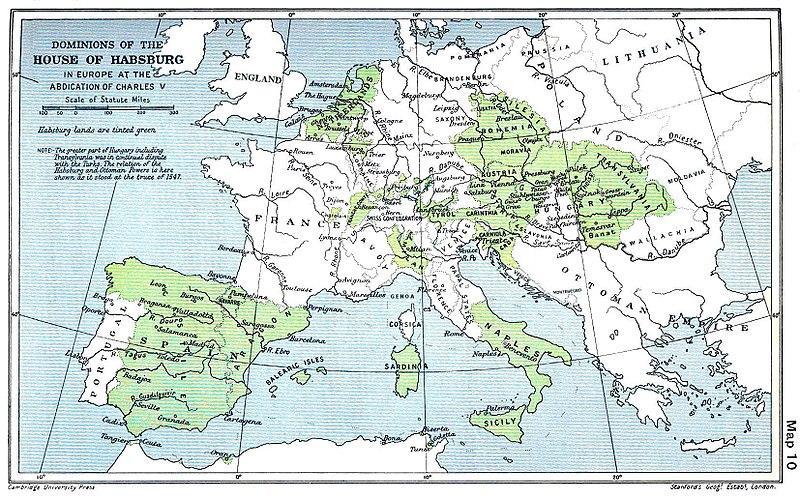

While the Holy Roman Empire was thus a far cry from the increasingly centralized states of Western Europe, the Habsburgs were unquestionably one of the most powerful royal lines, and their own territories stretched from Hungary to the New World by the sixteenth century. The greatest emperor (in terms of the sheer amount of territory he ruled) was Charles V, who ruled from 1519 – 1558. A grandson of Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain, Charles inherited a gargantuan amount of territory.

The sheer number and variety of Charles V’s territorial possessions and related titles strikes almost comical levels from a contemporary perspective. He was emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and king of Spain, Grand Duke of various territories in Poland and Romania, princely count of southern German lands, duke of others, and even claimed sovereignty over Jerusalem (although of course he did not actually control the Holy Land). Most of these titles were not the result of military conquests – they were places he had inherited from his ancestors. The unofficial Habsburg motto was “Let others wage war. You, happy Austria, marry to prosper.” Charles ruled not only the Habsburg possessions in Europe, but the enormous new (Spanish) empire that had emerged in the New World since the late fifteenth century.

The European possessions of Charles V. Note how his territories were non-contiguous (i.e. they were not geographically united) because they were primarily the results of lands he inherited from various ancestors.

Ironically, Charles himself had a terrible time managing anything, despite his personal intelligence and competence. He proved unable to contain the explosion of the Protestant Reformation, he was engaged in ongoing defensive wars against both France and the Turks, and his territories were so far-flung that he spent most of his life traveling between them. He eventually abdicated in 1558, and recognizing that the Habsburg lands were almost ungovernable, he handed power over to his brother Ferdinand I in Austria (Ferdinand also became Holy Roman Emperor) and his son Philip II in Spain and its possessions. Henceforth, the two branches of the Habsburgs were united in their Catholicism and their enmity with France, but little else.

Image Citations (Creative Commons):

Habsburg lands: public domain

This chapter has been derived with modifications from Chapter 4: Politics in the Renaissance Era in Western Civilization: A Concise History.